268

Chapter 9

Capital Budgeting Decision Models

LEARNING OBJECTIVES (Slides 9-2 to 9-3)

1. Explain capital budgeting and differentiate between short-term and long-term

budgeting decisions.

2. Explain the payback model and its two significant weaknesses and how the

discounted payback period model addresses one of the problems.

3. Understand the net present value (NPV) decision model and appreciate why it is the

preferred criterion for evaluating proposed investments.

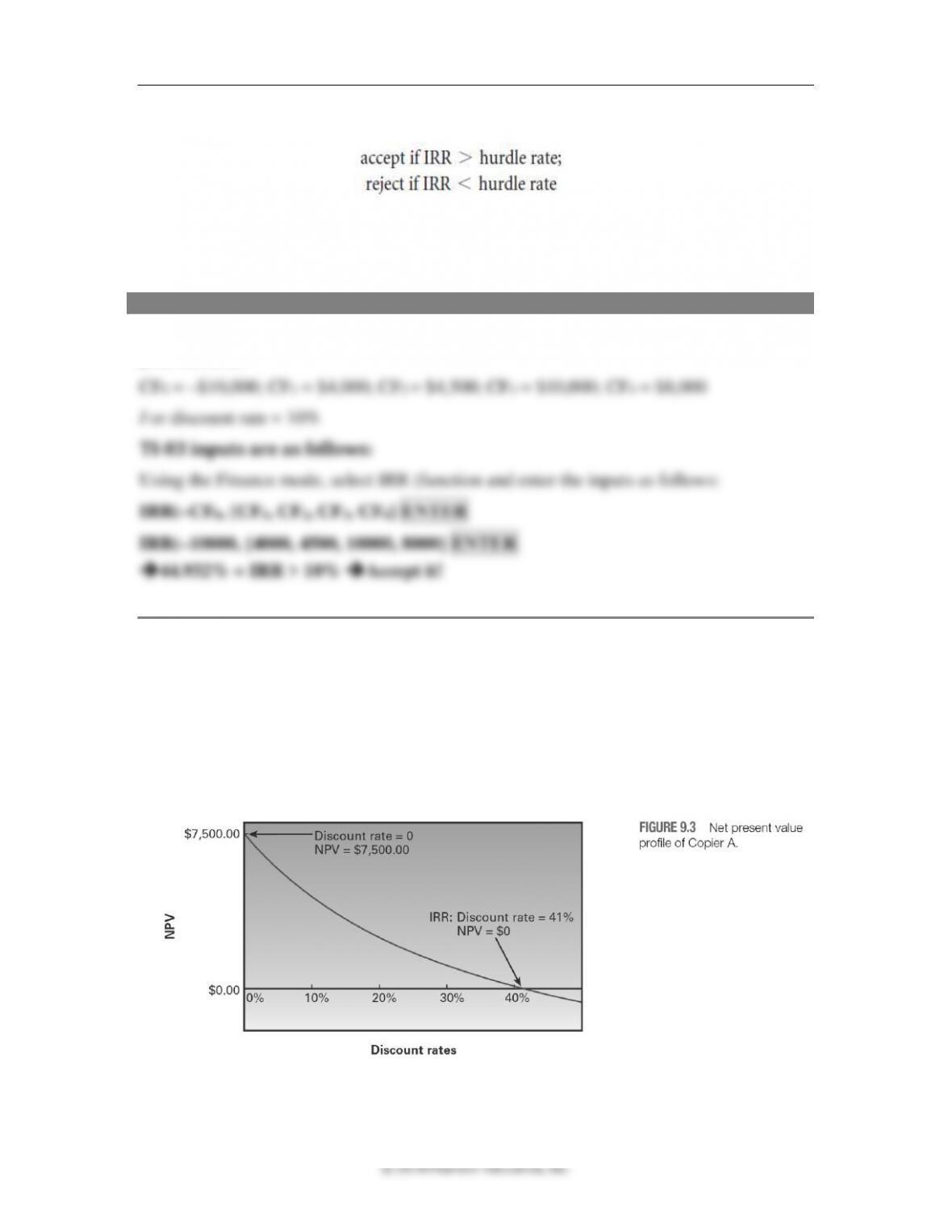

4. Calculate the most popular capital budgeting alternative to the NPV, the internal rate

of return (IRR); and explain how the modified internal rate of return (MIRR) model

attempts to address the IRR’s problems.

5. Understand the profitability index (PI) as a modification of the NPV model.

6. Compare and contrast the strengths and weaknesses of each decision model in a

holistic way.

IN A NUTSHELL…

In this chapter, the author explains the various capital budgeting techniques that can be

used to make informed investment decisions involving productive assets such as plant

and equipment, machinery, etc. In particular, six alternative evaluations techniques are

covered including the payback period, the discounted payback period, the net present

value (NPV) model, the internal rate of return (IRR) criterion, the modified internal rate

of return model (MIRR), and the profitability index (PI). After illustrating and explaining

in detail how each technique is to be used, the strengths and weaknesses of each decision

model are summarized. This chapter sets the stage for the material in the next chapter,

which involves the forecasting and analysis of project cash flows.

LECTURE OUTLINE

9.1 Short-Term and Long-Term Decisions (Slides 9-4 to 9-5)

Long-term decisions, typically, involve longer time horizons, cost larger sums of money,

and require a lot more information to be collected as part of their analysis compared to

short-term decisions. The investment of funds into capital or productive assets, which is

what capital budgeting entails, meets all three of these criteria and therefore is considered

a long-term decision. The efficacy of capital budgeting decisions can have long-term

effects on a firm and are thus to be made with considerable thought and care. Three keys

things should be remembered about capital budgeting decisions: