528 Brooks ◼ Financial Management: Core Concepts, 4e

© 2018 Pearson Education, Inc.

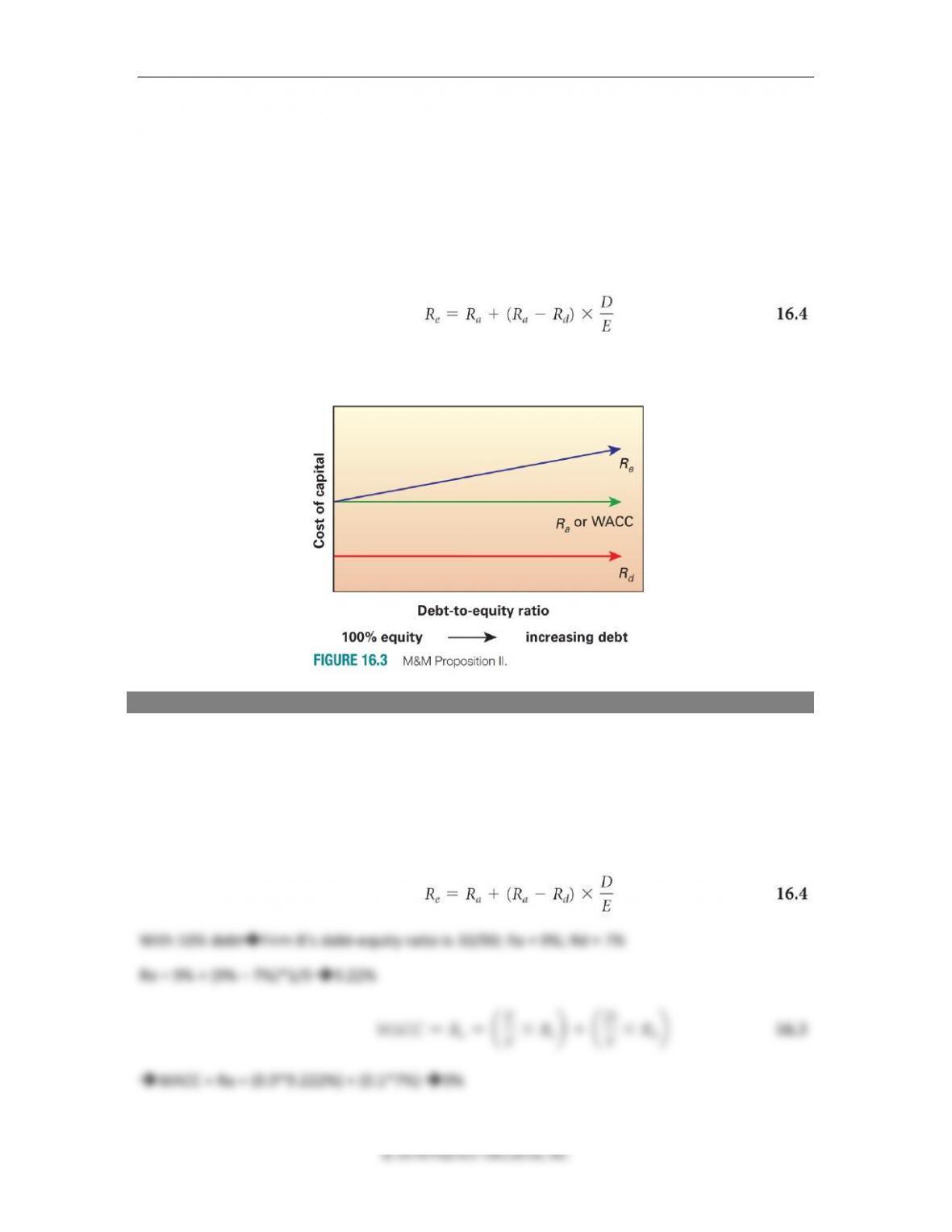

With 40% debt➔D/E = 40/60

Re = 9% + (9% – 7%)*0.667➔10.334%

WACC = 0.6*10.334% + 0.4*7% ➔9%

With 90% debt➔D/E = 90/10

Re = 9% + (9% – 7%)*9 ➔27%

WACC = 0.1*27% + 0.9*7% ➔9%

Because the WACC of the levered firm is the same as that of the all-equity firm (9%) in all three

scenarios, we can say that debt does not matter.

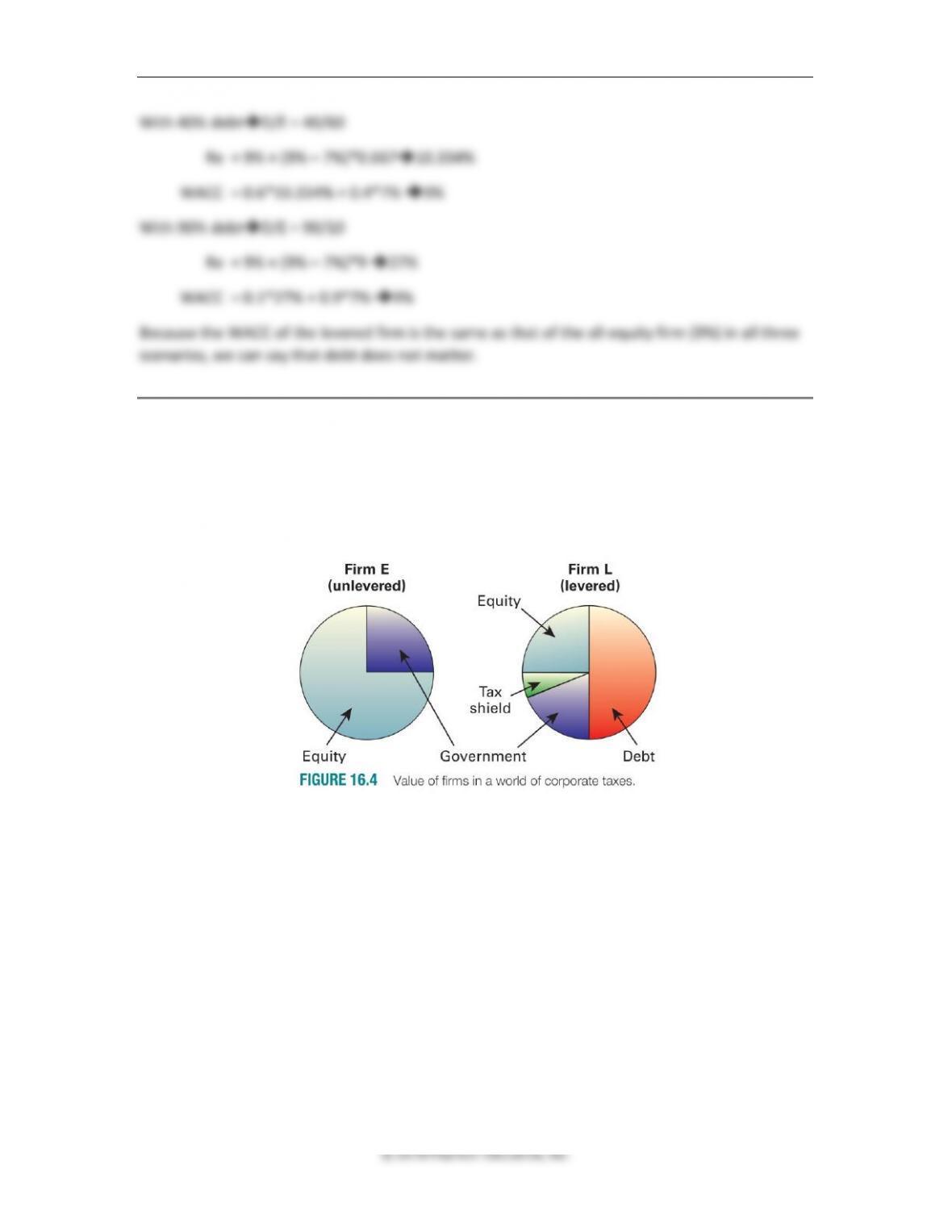

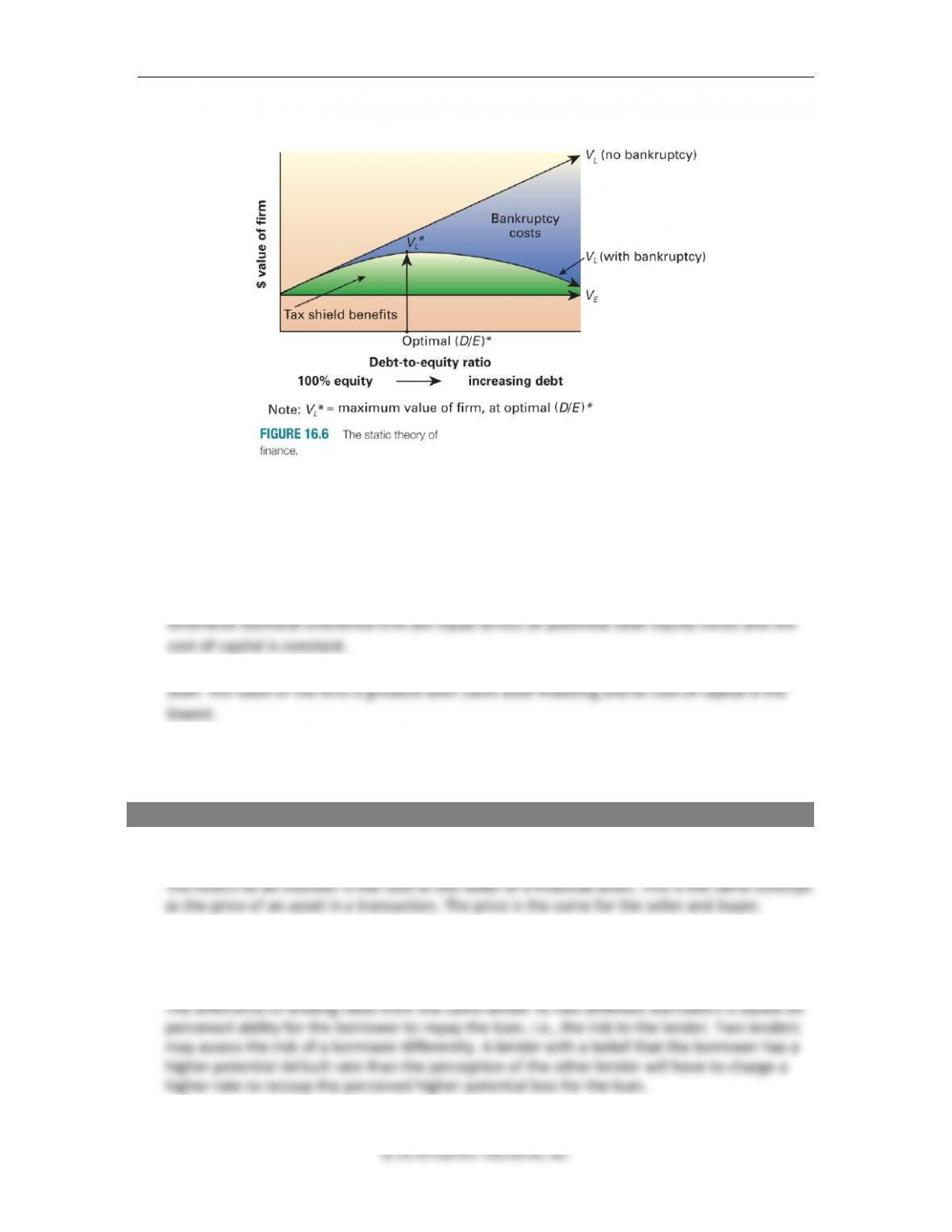

Capital Structure in a World of Corporate Taxes and No Bankruptcy

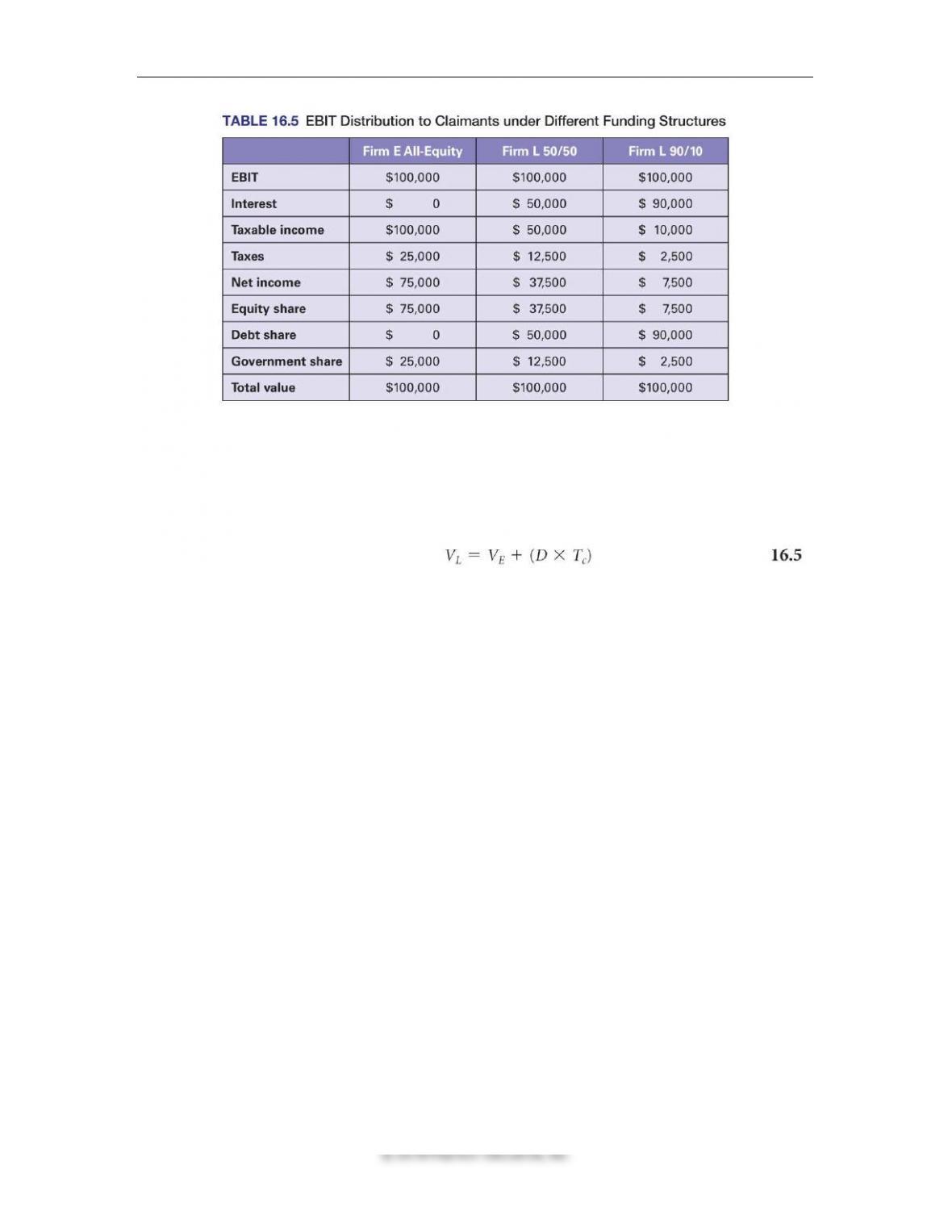

Once M&M injected some reality into their capital structure discussion, i.e., that taxes are a way

of life, their Propositions I and II got turned around. With interest being tax-deductible, the

levered firm pays less tax on its income than an all-equity firm, and the equity holders enjoy

more in residual profits as portrayed in Figure 16.4.

As the firm issues more debt, its tax shield increases, and the government’s share of the pie

decreases, increasing the value of the equity holders.

The new Propositions I and II are as follows:

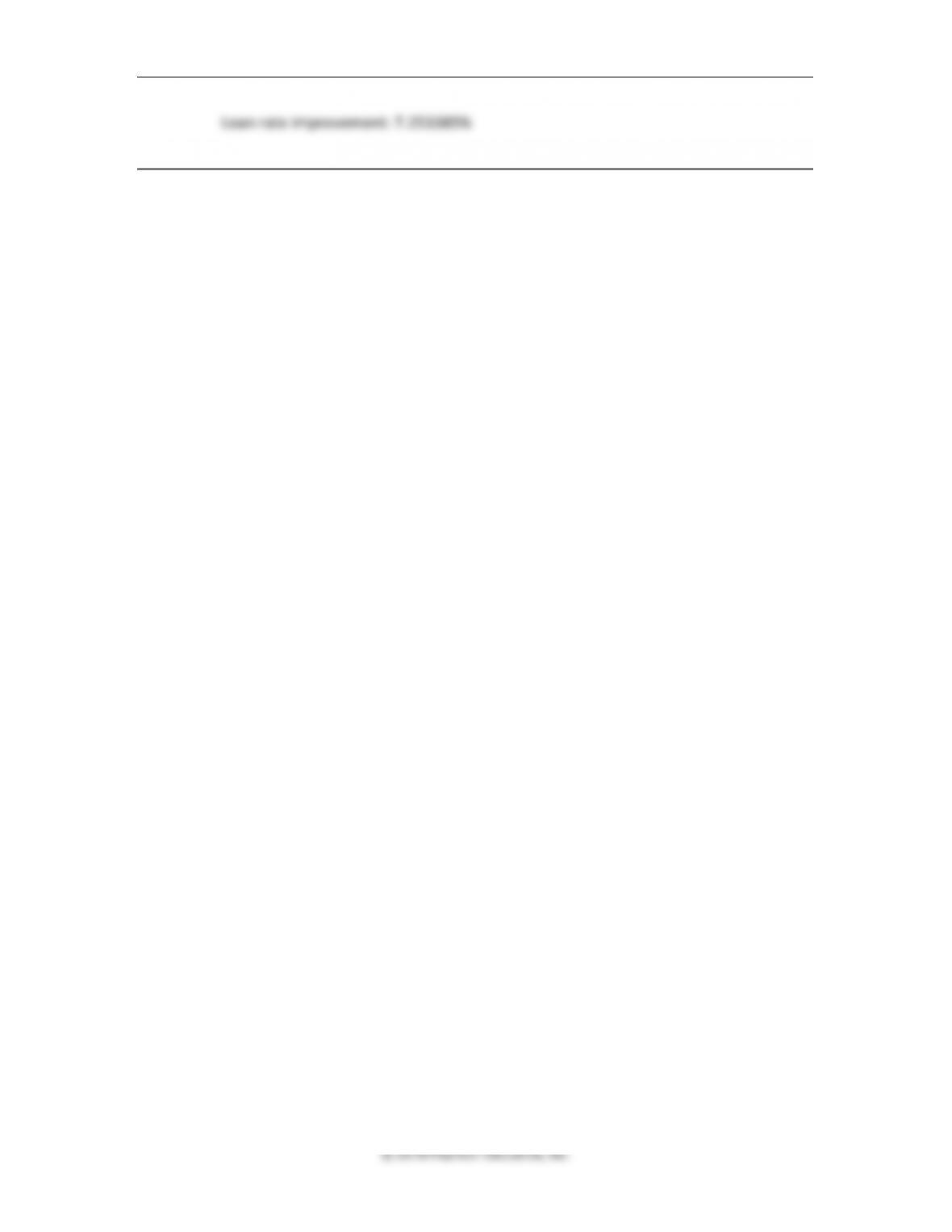

Proposition I, with taxes: All debt financing is optimal.

Proposition II, with taxes: The WACC of the firm falls as more debt is added.

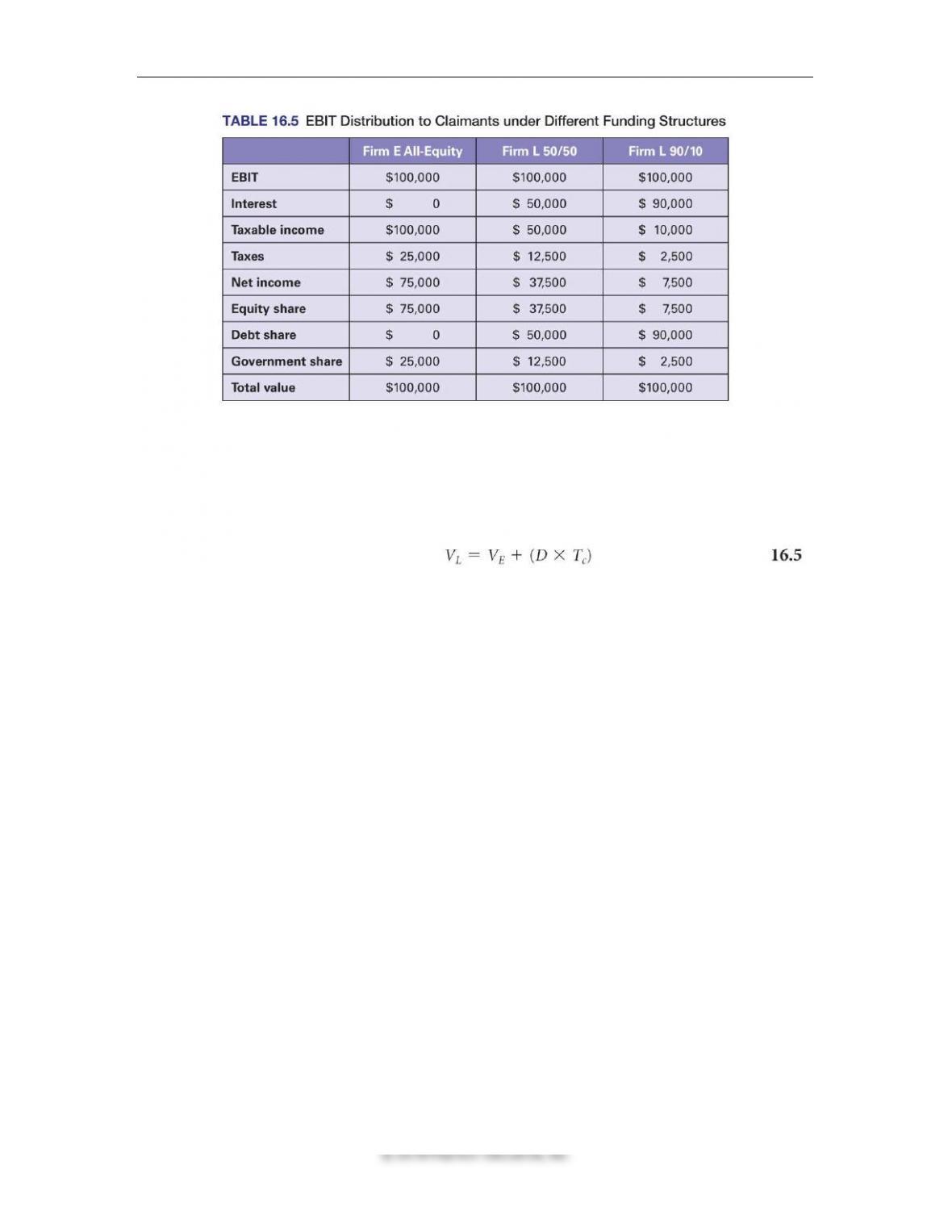

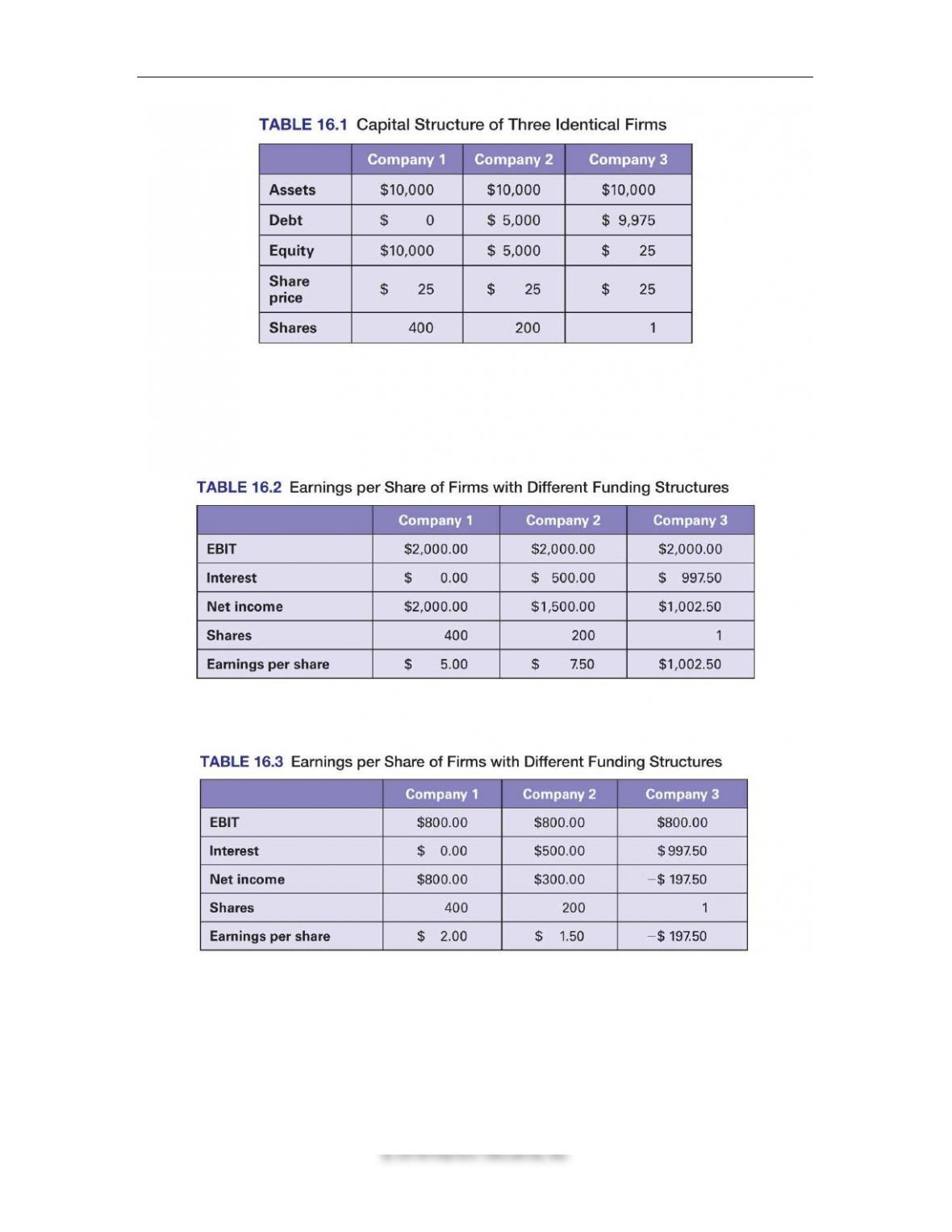

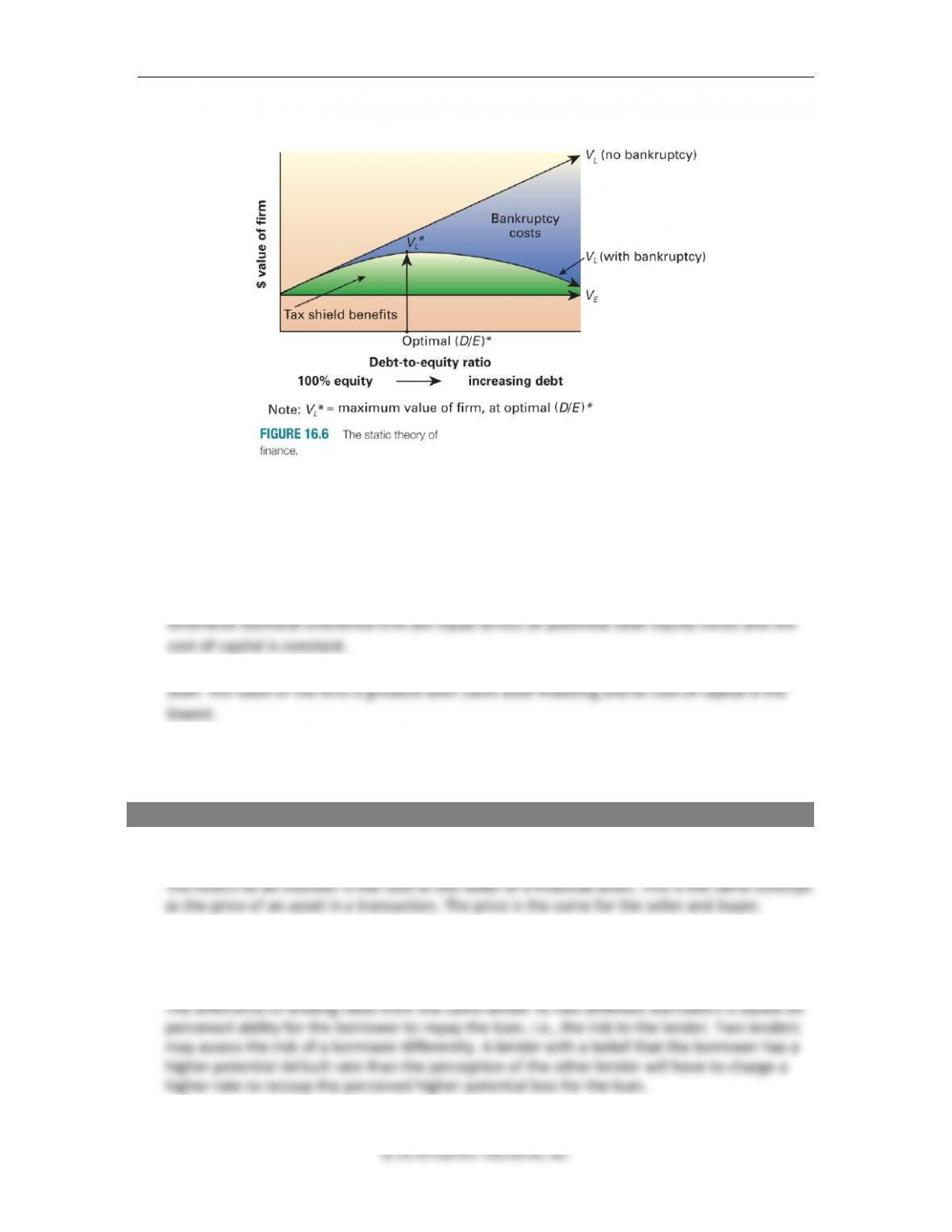

Debt and the Tax Shield: Table 16.5 shows the effect of increasing debt levels on the

distribution of a firm’s EBIT.