Chapter 10 ◼ Cash Flow Estimation 331

depreciation (which had been deducted in Figure 10.1, mainly for tax purposes) is added back.

Thus,

10.2 Estimating Cash Flow for

Projects: Incremental Cash Flow (Slides 10-6 to 10-14)

When a firm is considering either expanding a current line of business, starting a new venture,

or replacing an existing asset with a newer one, the changes in revenue and costs that occur will

have an incremental effect on its operating cash flow.

It is the timing and magnitude of these incremental cash flows that have to be carefully

estimated and evaluated as part of any capital budgeting analysis.

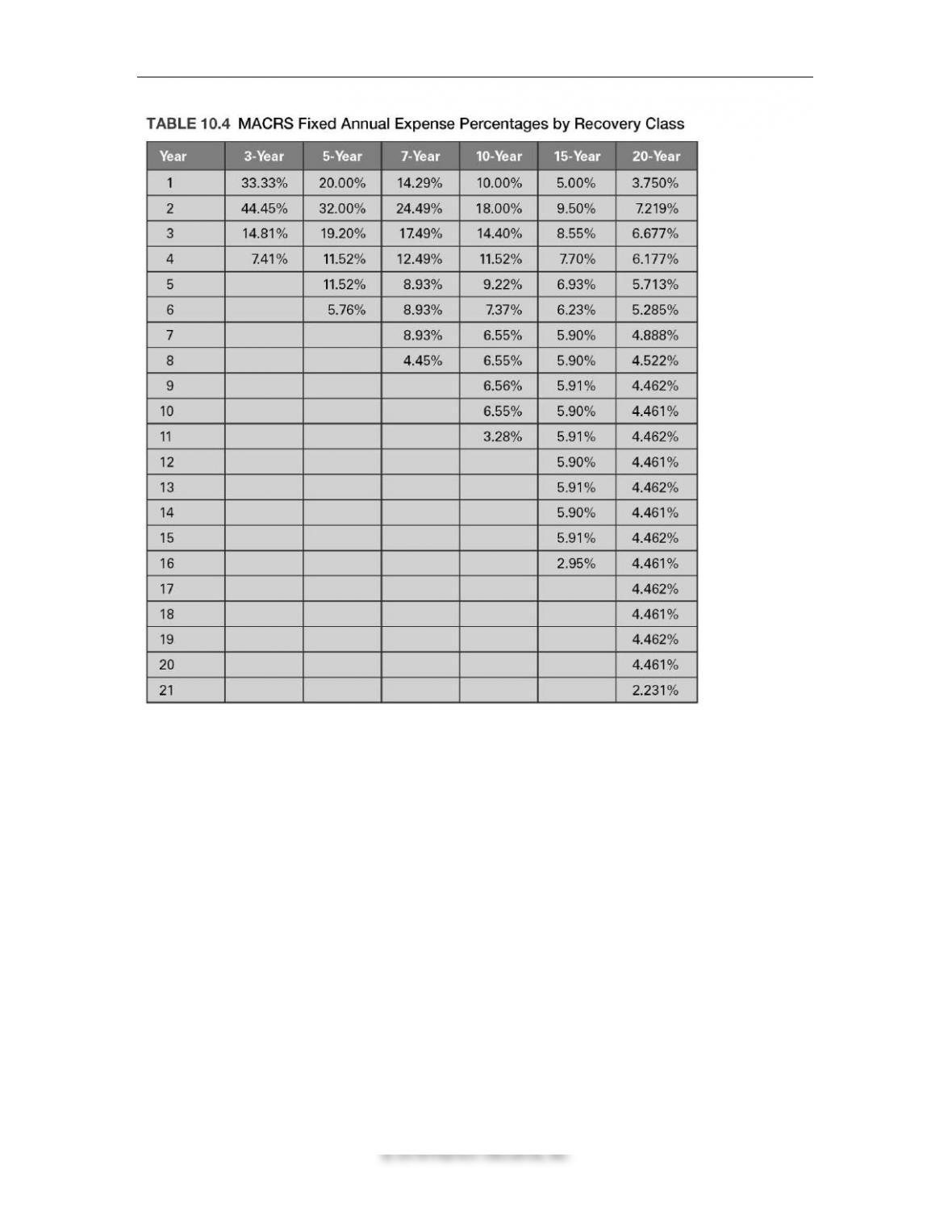

Seven important issues need to be tracked during a comprehensive cash flow estimation

process. These issues include sunk costs, opportunity cost, erosion, synergy gains, working

capital, capital expenditures, and depreciation or cost recovery of assets.

Sunk costs are expenses that have already been incurred, or that will be incurred, regardless of

the decision to accept or reject a project. For example, a marketing research study exploring

business possibilities in a region would be a sunk cost, since its expenditure has been done prior

to undertaking the project and will have to be paid whether or not the project is taken on. These

costs, although part of the income statement, should not be considered as part of the relevant

cash flows when evaluating a capital budgeting proposal.

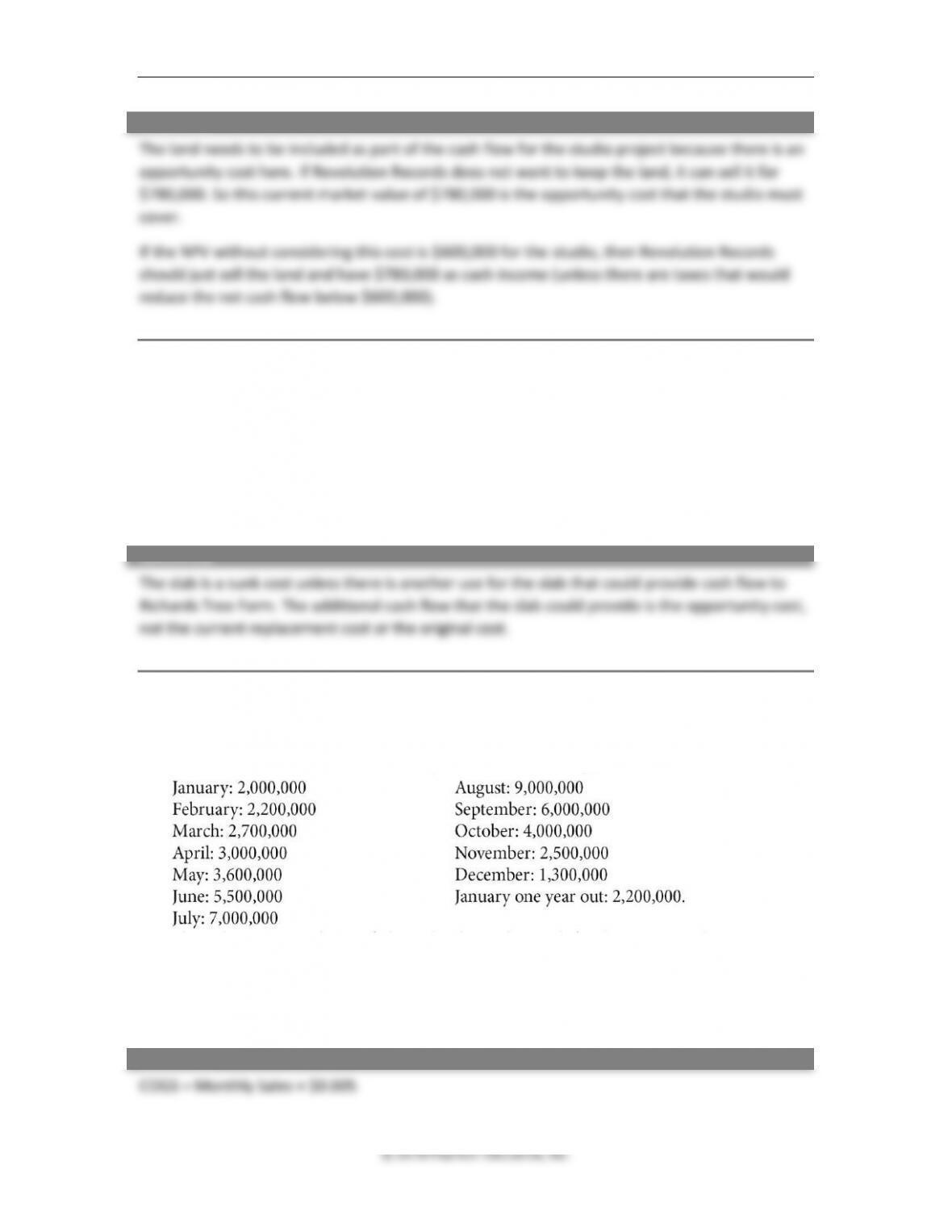

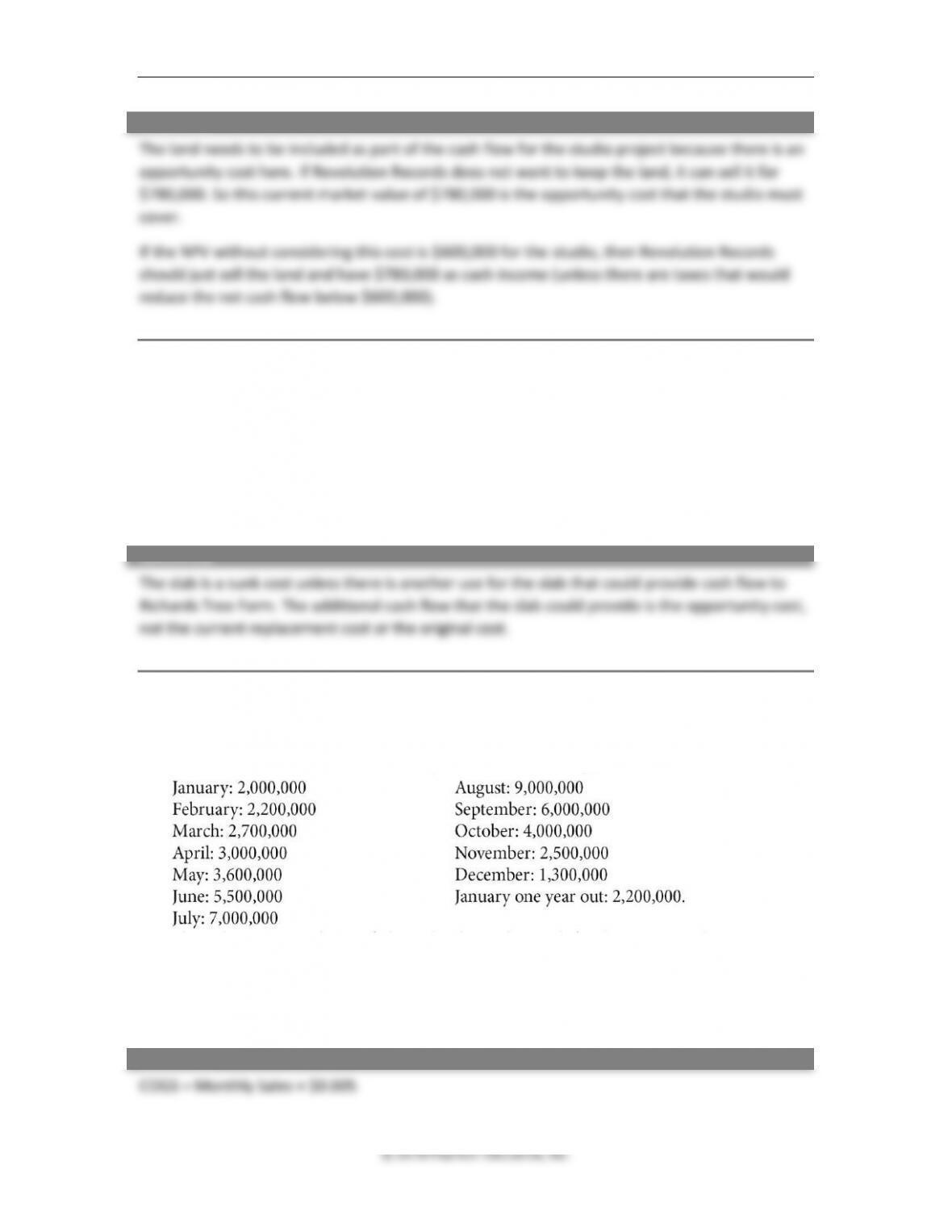

Opportunity costs include costs that may not be directly observable or obvious, but result

from benefits being lost as a result of taking on a project. For example, if a firm decides to use

an idle piece of equipment as part of a new business, the value of the equipment that could be

realized by either selling or leasing it would be a relevant opportunity cost.

Erosion costs arise when a new product or service competes with revenue generated by a

current product or service offered by a firm. For example, if a store offers two types of photo-

copying services, a newer, more expensive choice and an older economical one, some of the

revenues from the older repeat customers will be lost and should therefore be accounted for in

the incremental cash flows.

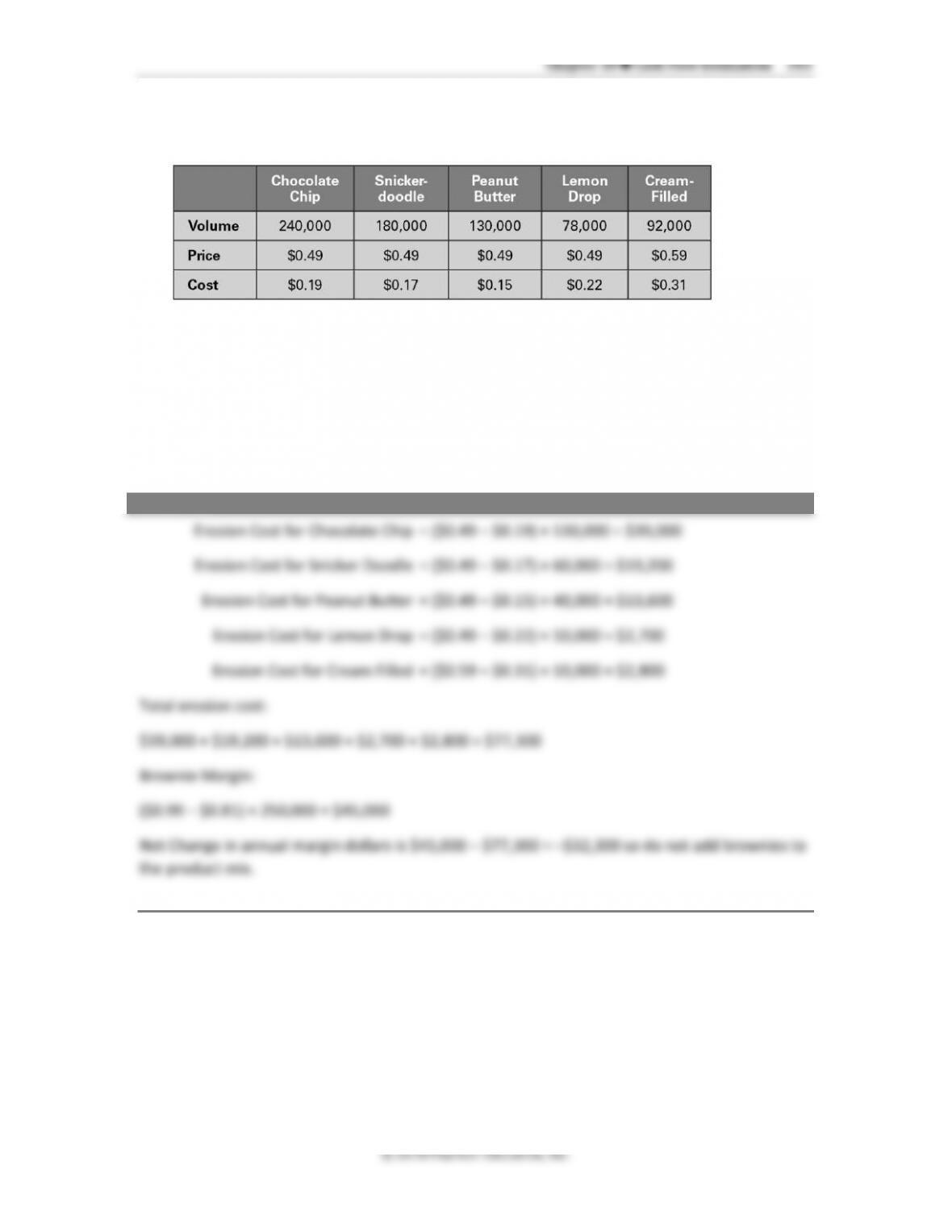

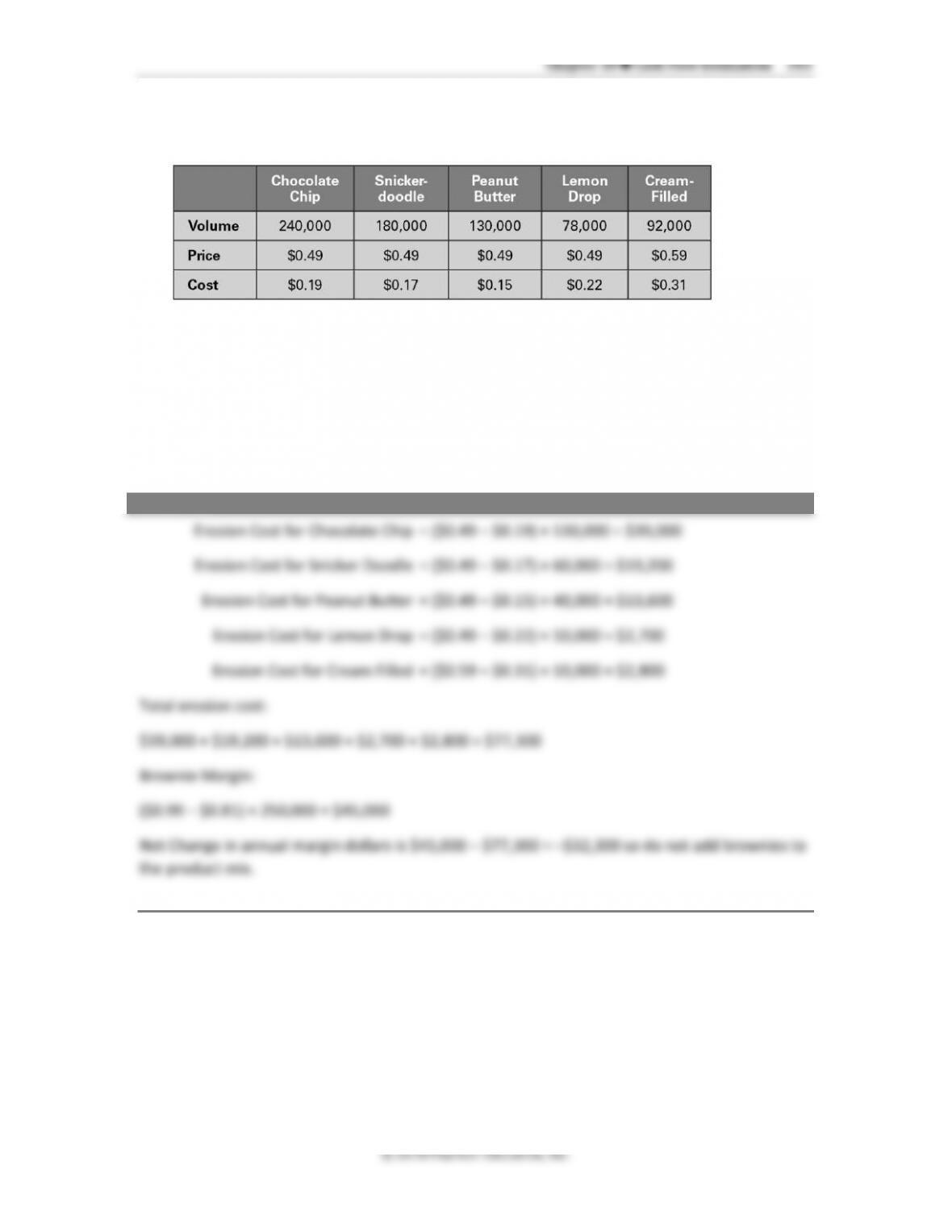

Example 1: Erosion costs

Frosty Desserts currently sell 100,000 of its Strawberry-Shortcake Delight each year for $3.50

per serving. Its cost per serving is $1.75. Its chef has come up with a newer, richer concoction,

“Extra-Creamy Strawberry Wonder,” which costs $2.00 per serving, will retail for $4.50 and

should bring in 130,000 customers. It is estimated that after the launch the sales for the original

variety will drop by 15%. Estimate the erosion cost associated with this venture.