Chapter 3

The Double-Entry Accounting System

General Comments for Chapter 3

Chapter 3 introduces recording procedures at a level designed to serve students who plan to

major in accounting as well as those who do not. Although advances in computer technology

have reduced the importance of recording procedures, debit and credit terminology continues

to be used in everyday business practice. Banks issue debit and credit cards. Customers are

told that their accounts have been debited or credited. Most medium- to large-size businesses

account for transactions using double-entry accounting with debits and credits. Therefore,

general business students as well as accounting majors need exposure to double-entry termi-

nology.

The traditional approach introduces technical terminology too early and in too much depth.

We believe you will find the two previous chapters have provided your students a back-

ground that facilitates their ability to master recording procedures. In other words, teaching

debits and credits should be easier under the concepts approach.

This text does omit many of the more detailed topics found in traditional texts. For example,

it does not include worksheets, special journals, and posting references. It does not use an

income summary account. The revenue, expense, and dividends accounts are closed directly

to retained earnings. Accounting majors will see these topics in their intermediate course,

and other business majors do not need the procedural detail. The text provides appropriate

background without overburdening detail.

Detailed Outline of a Lesson Plan for Chapter 3

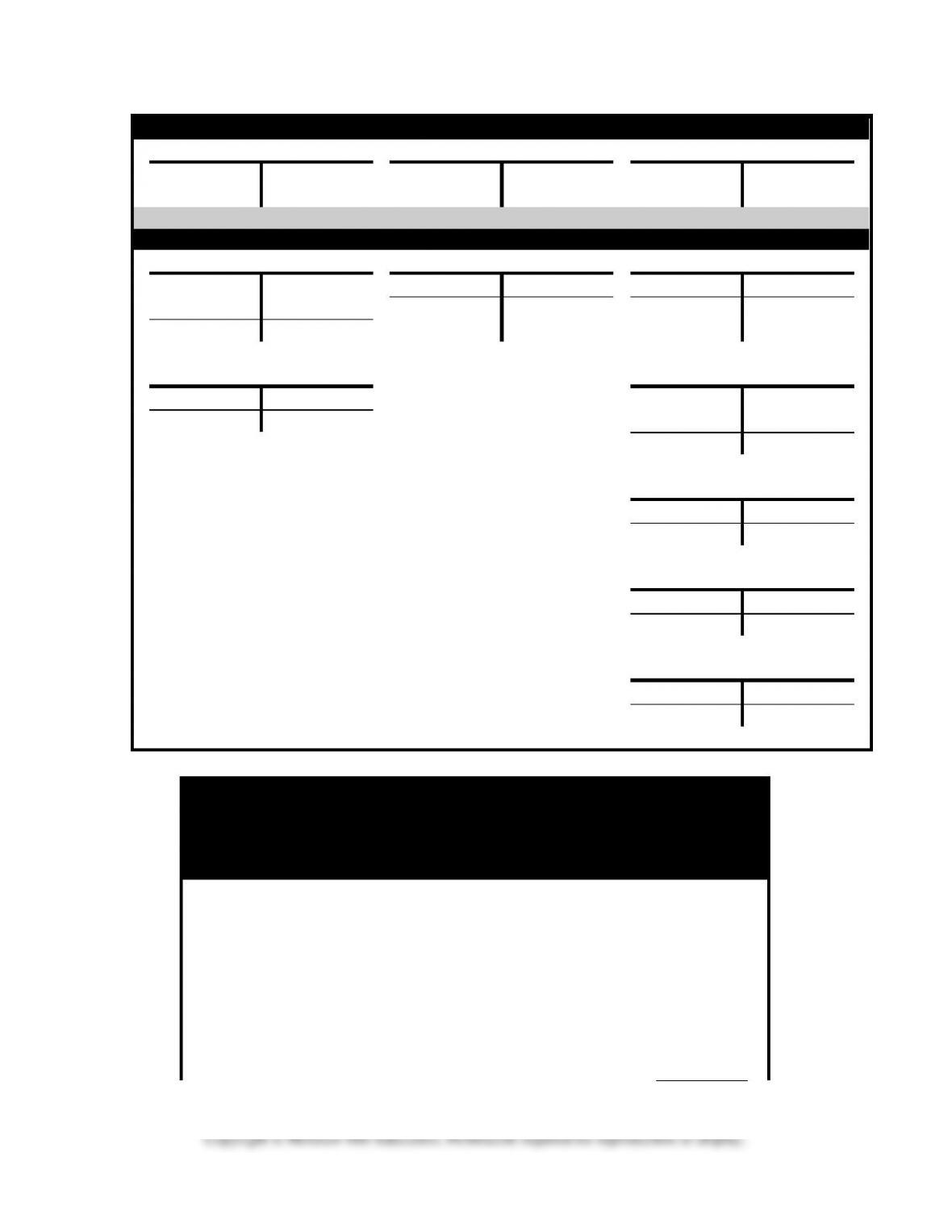

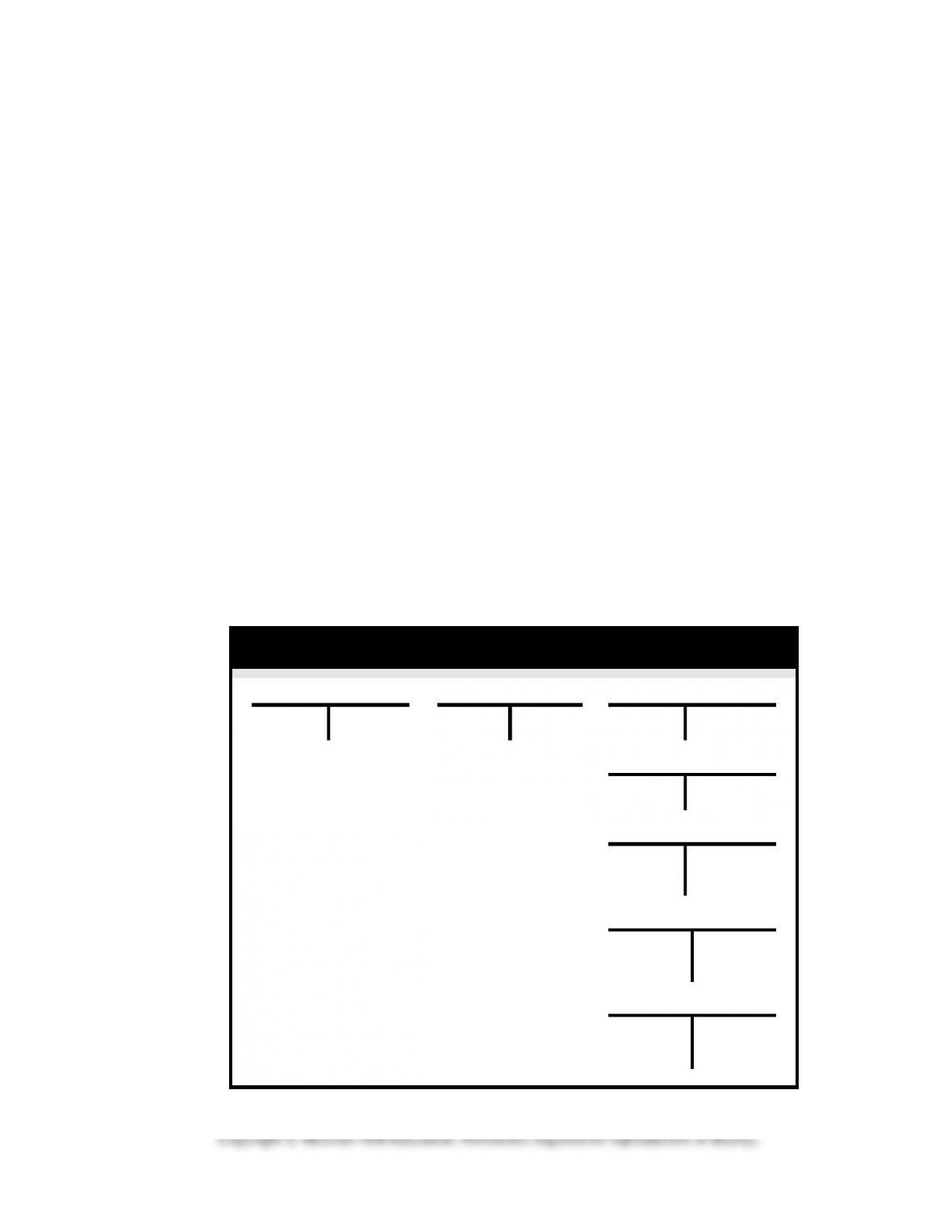

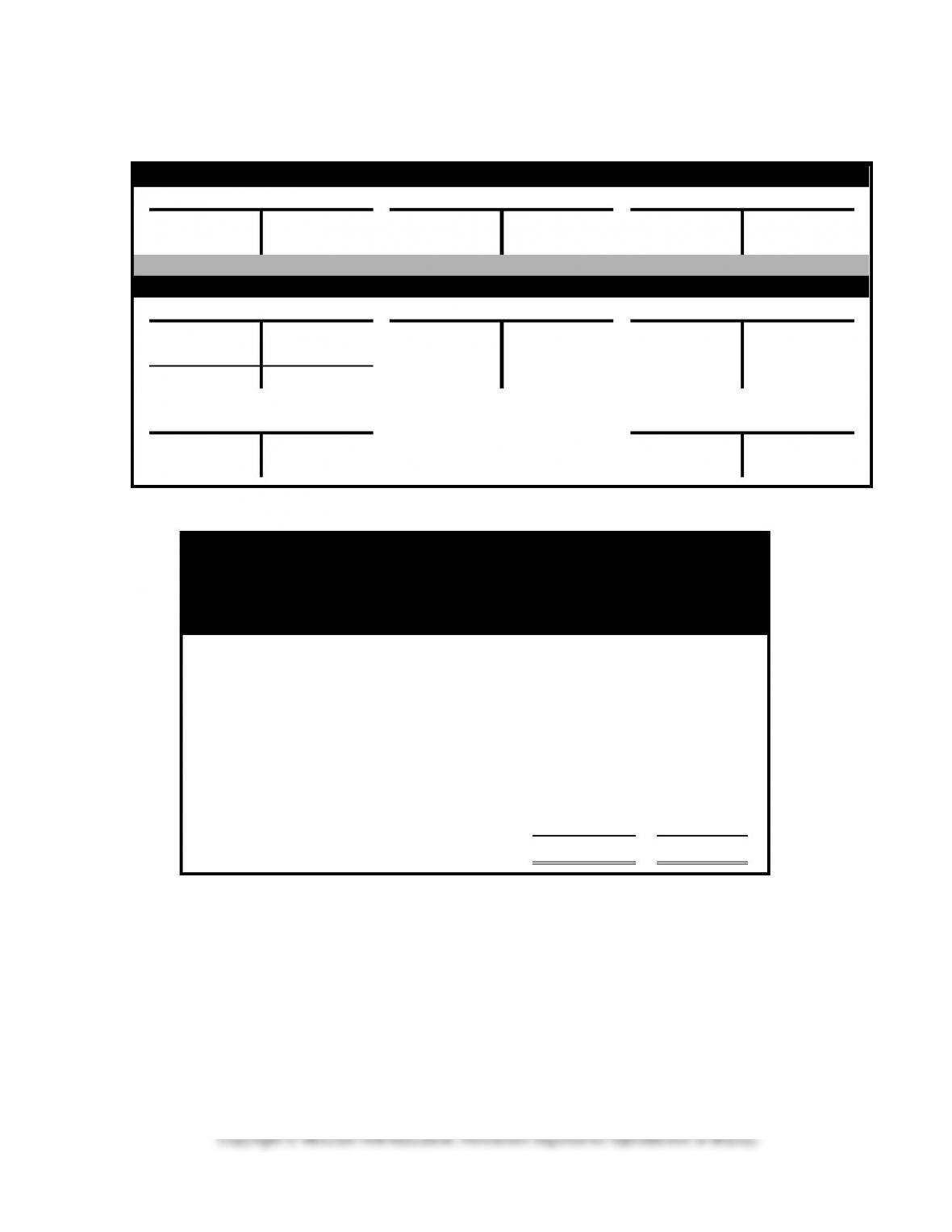

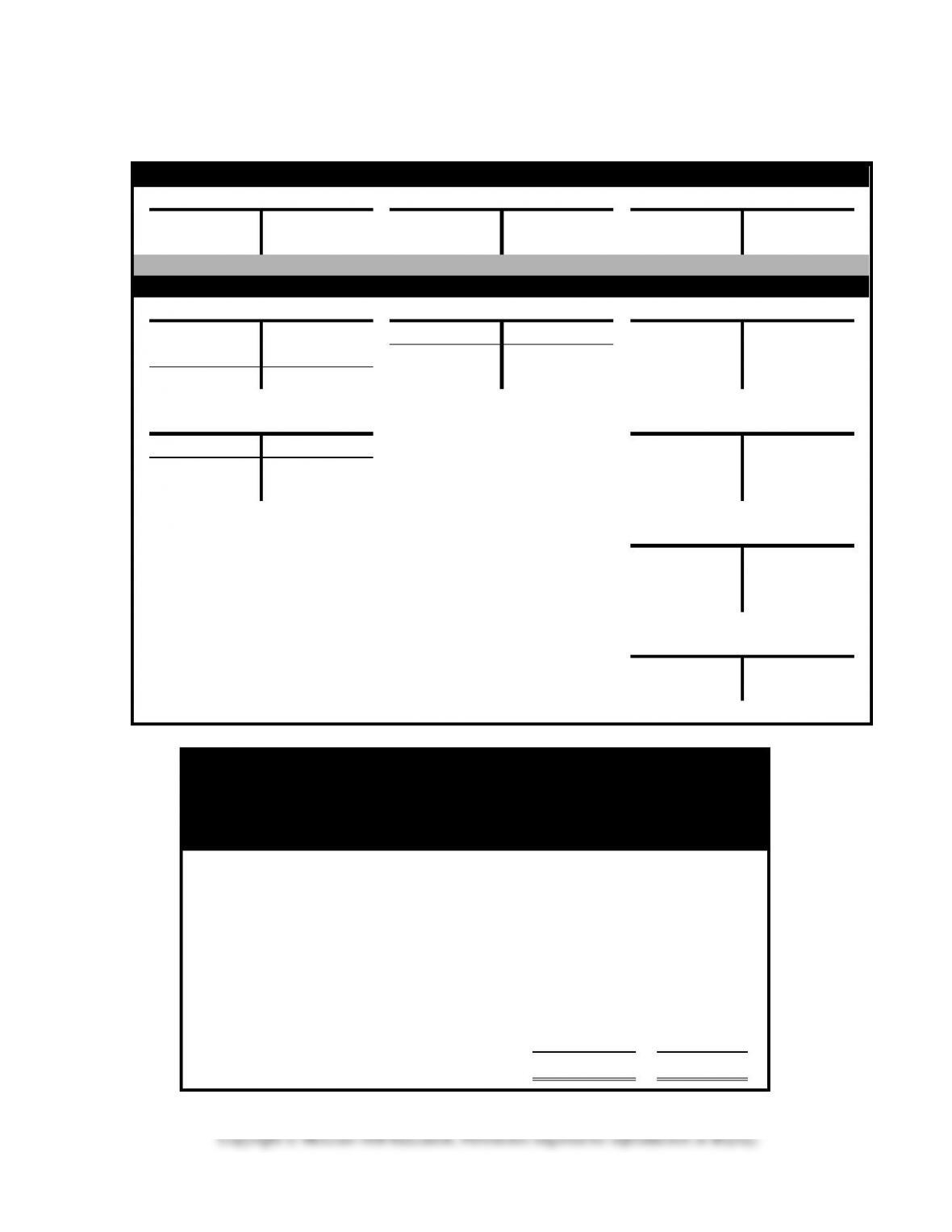

I. Begin by introducing T-accounts. Observe that using columns of pluses and minuses

becomes increasingly unmanageable as the number of transactions increases. Introduce

the T-account as a means of simplifying the recording of events. Draw a large T on the

board and then write the accounting equation such that the ‘=’ sign is over the vertical

part of the T with ‘Assets’ on the left side and ‘Claims’ on the right side of the ‘=’ sign.

This will help students understand that Assets balances are typically on the left side of

the T account and Claims balances – Liabilities and Equity are on the right side of the T

account. Next, draw a T-account on the board and write the word assets across the hor-

izontal bar. Reference the initial T account with the accounting equation and suggest

that for assets we record increases on the left side of the T and decreases on the right

side. Then complete the accounting equation by drawing T-accounts for liabilities and

equity and suggest that increases for liability and equity accounts are recorded on the

right side of the T and decreases on the left side. Add the terms debit and credit as the