Chapter 19 - Strategic Performance Measurement: Investment Centers

19-13

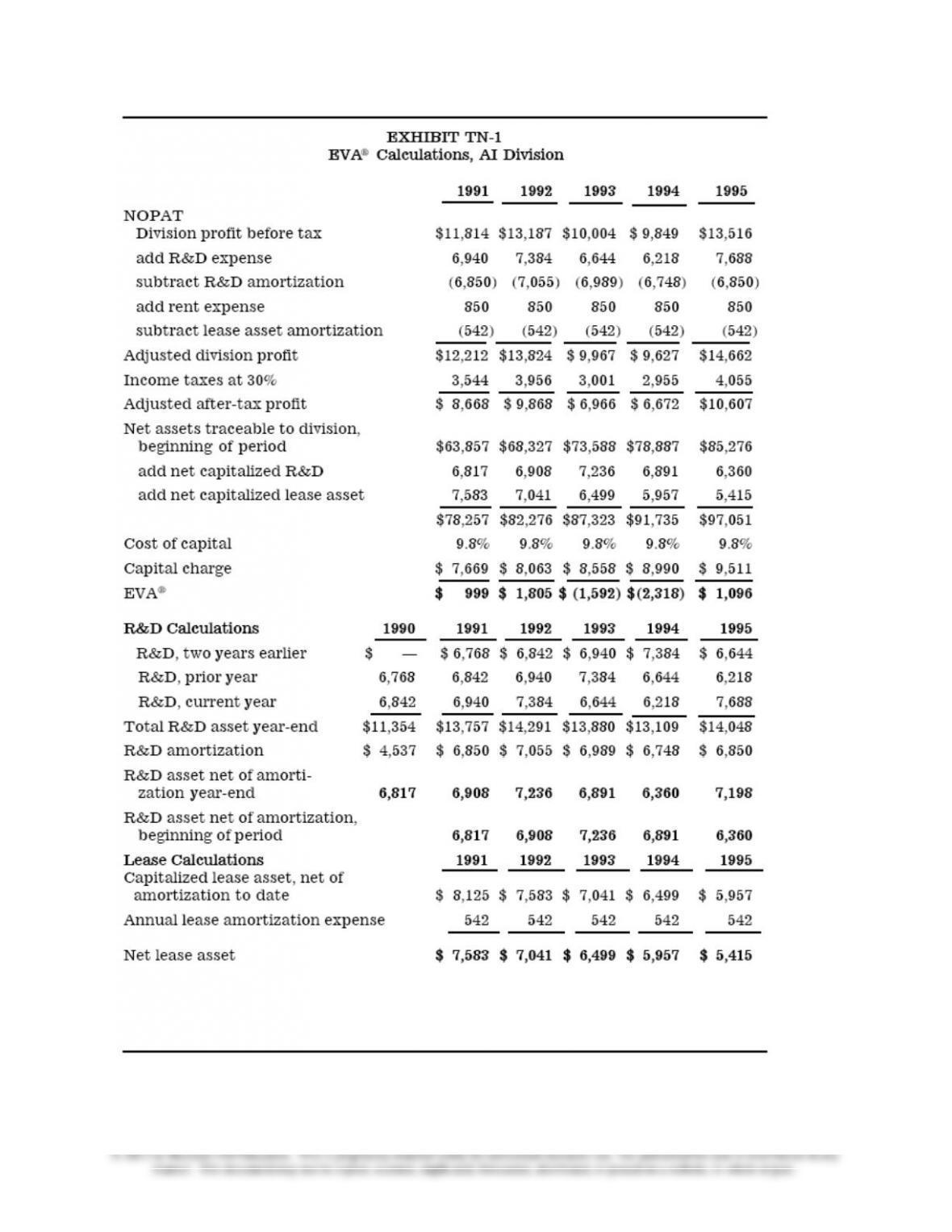

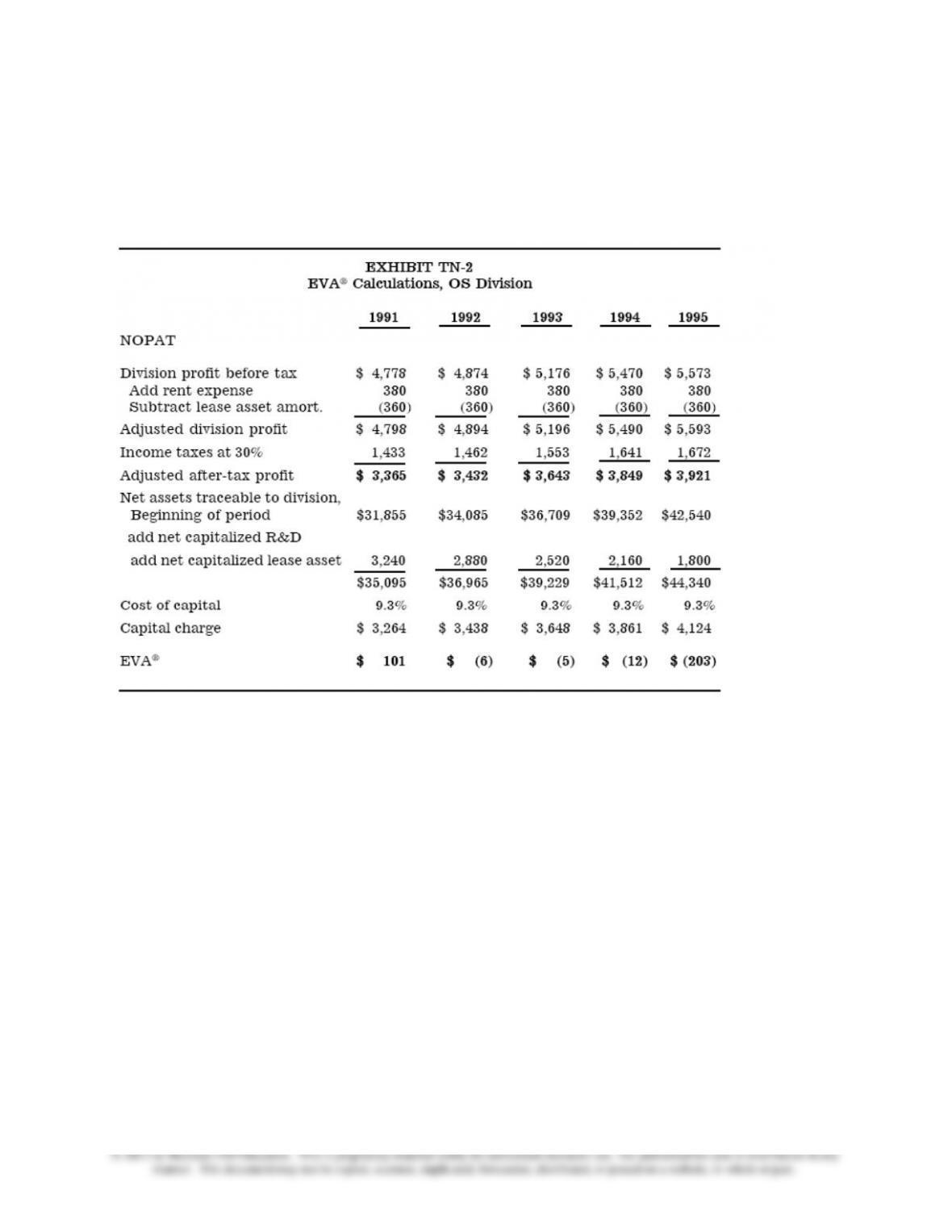

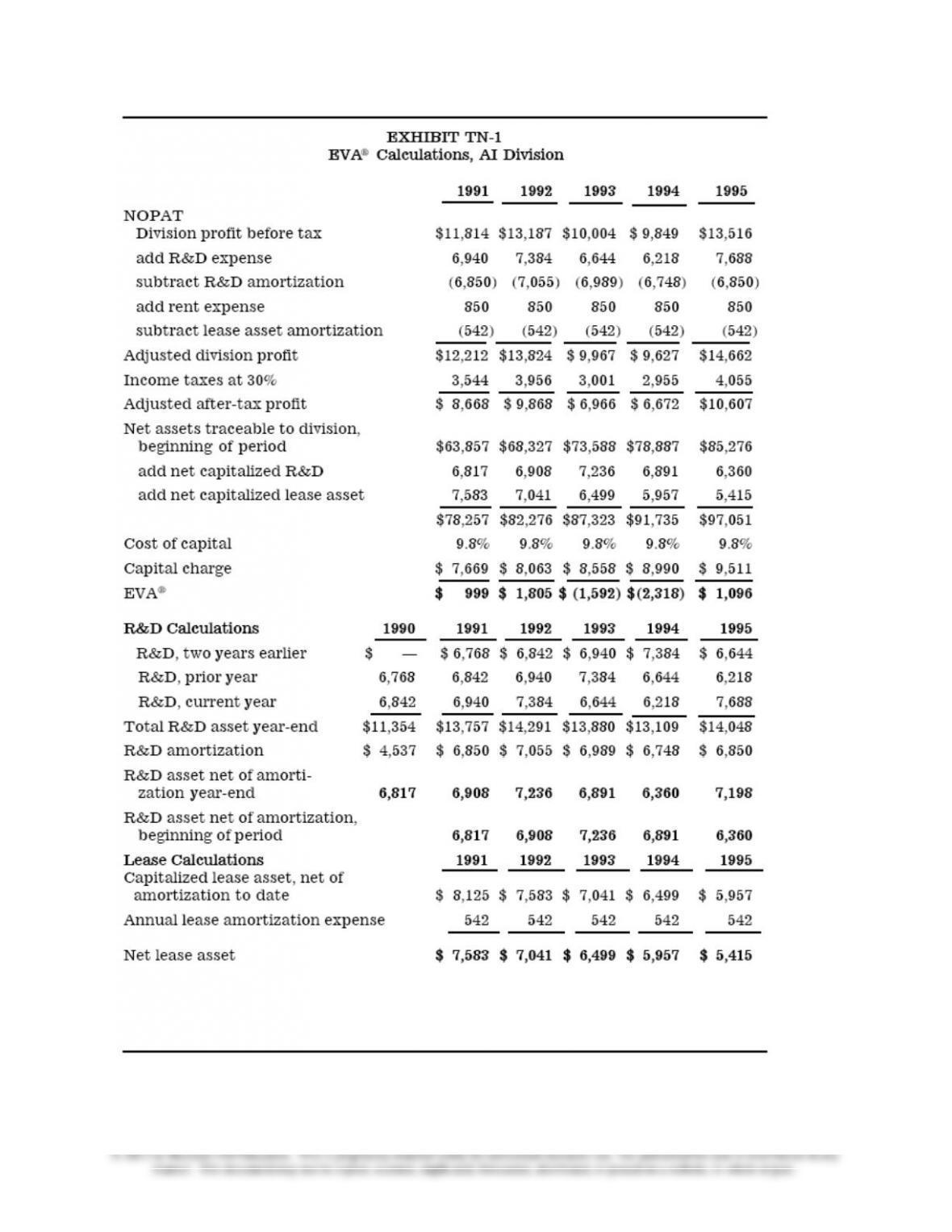

3. EVA® should mitigate but not eliminate incentives to emphasize short-run performance. Annual

EVA® is still based on a one-period historical model. However, accounting “distortions” such as the

requirement to expense R&D are “corrected” in calculating EVA®. In practice, EVA® compensation

plans are often implemented as rolling three-year targets in order to lengthen the managers’ planning

horizon.

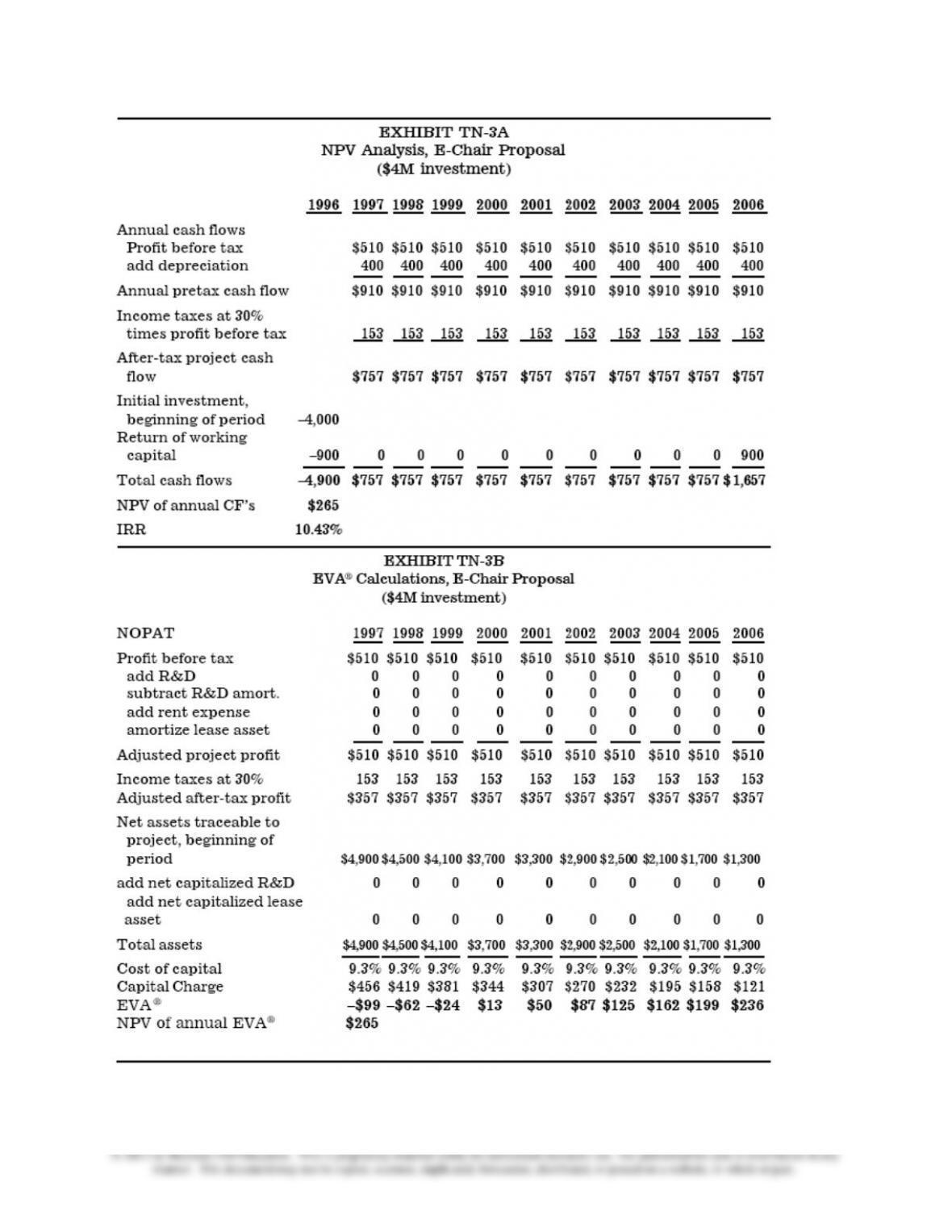

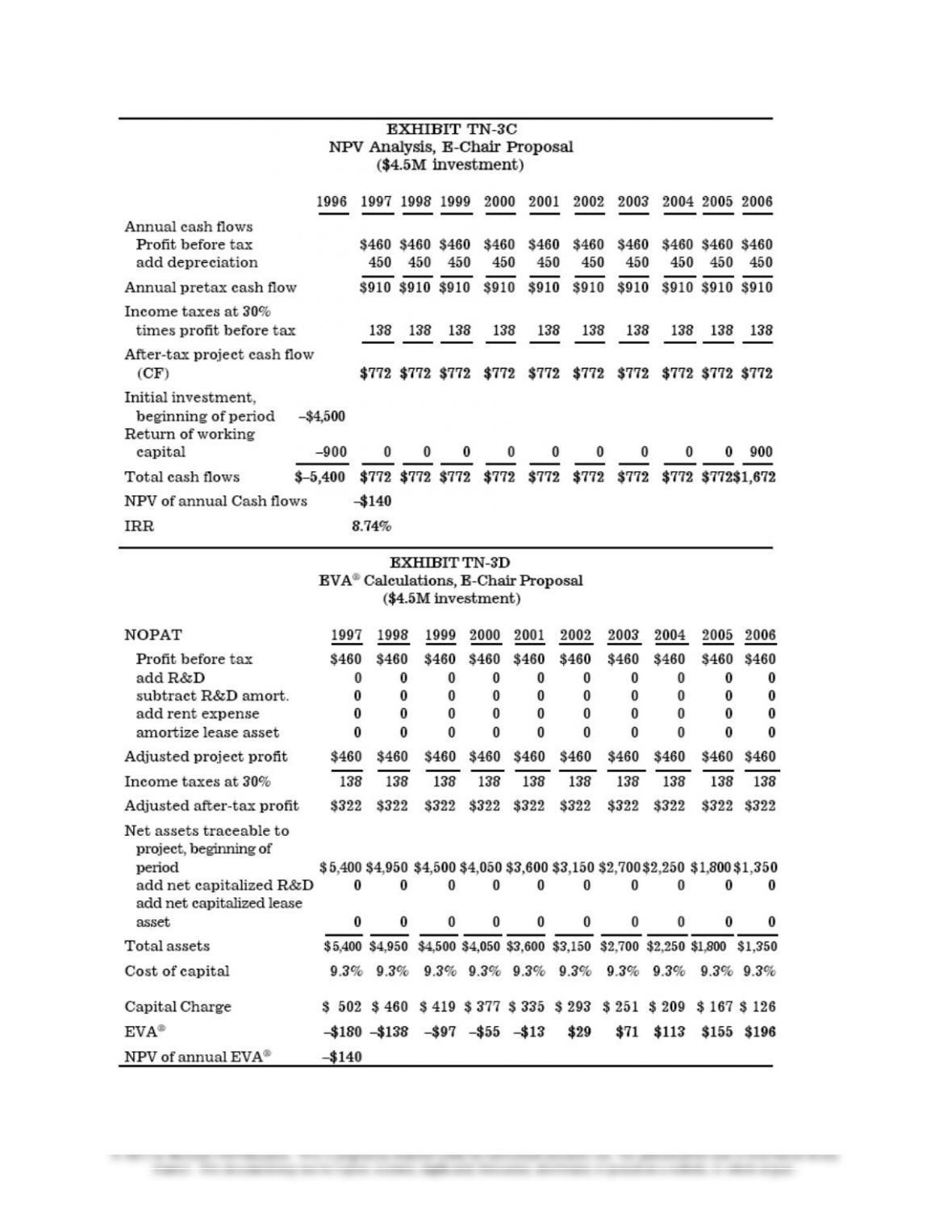

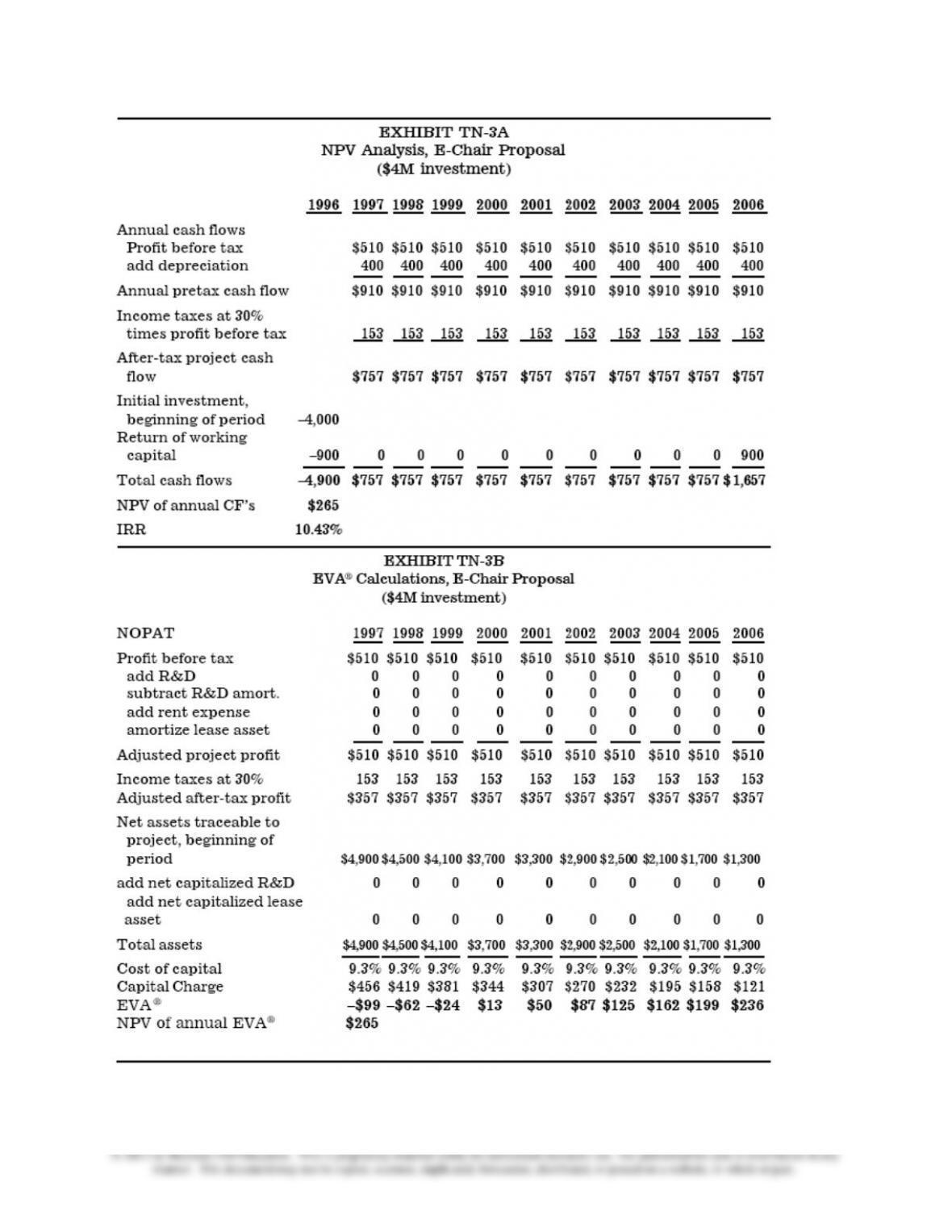

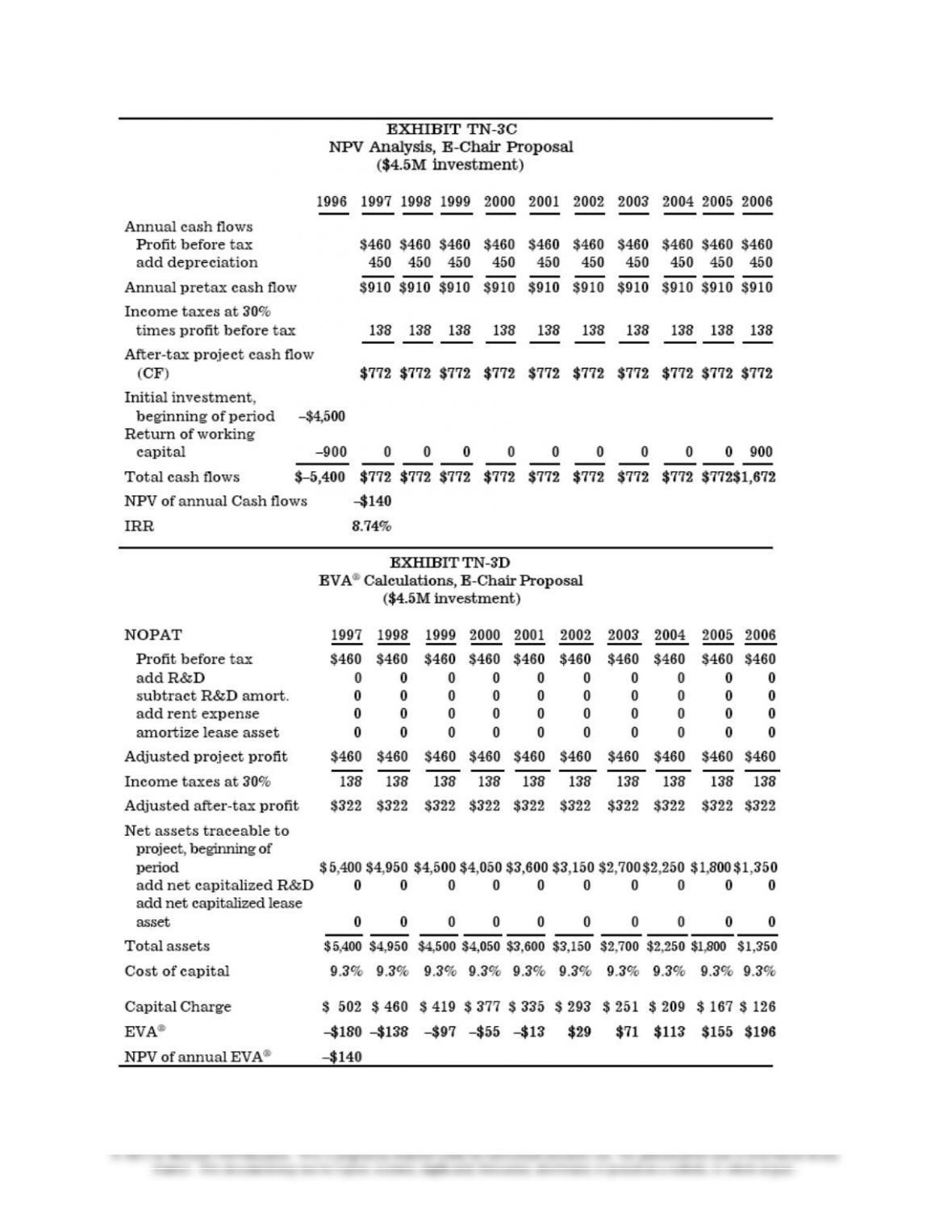

For example, without lengthening the time horizon, a proposal might be rejected because it produces

negative EVA® in the early years despite having large positive EVA® in future years. This could be the

case with the E-chair proposal if the initial investment in depreciable assets is at the low end of the range,

e.g., $4 million. See discussion of case question 1 above. An alternative means of mitigating manager’s

rejecting positive NPV projects with early losses is to use a form of economic depreciation where lesser

amounts of depreciation is taken in the early years (i.e., decelerated depreciation).

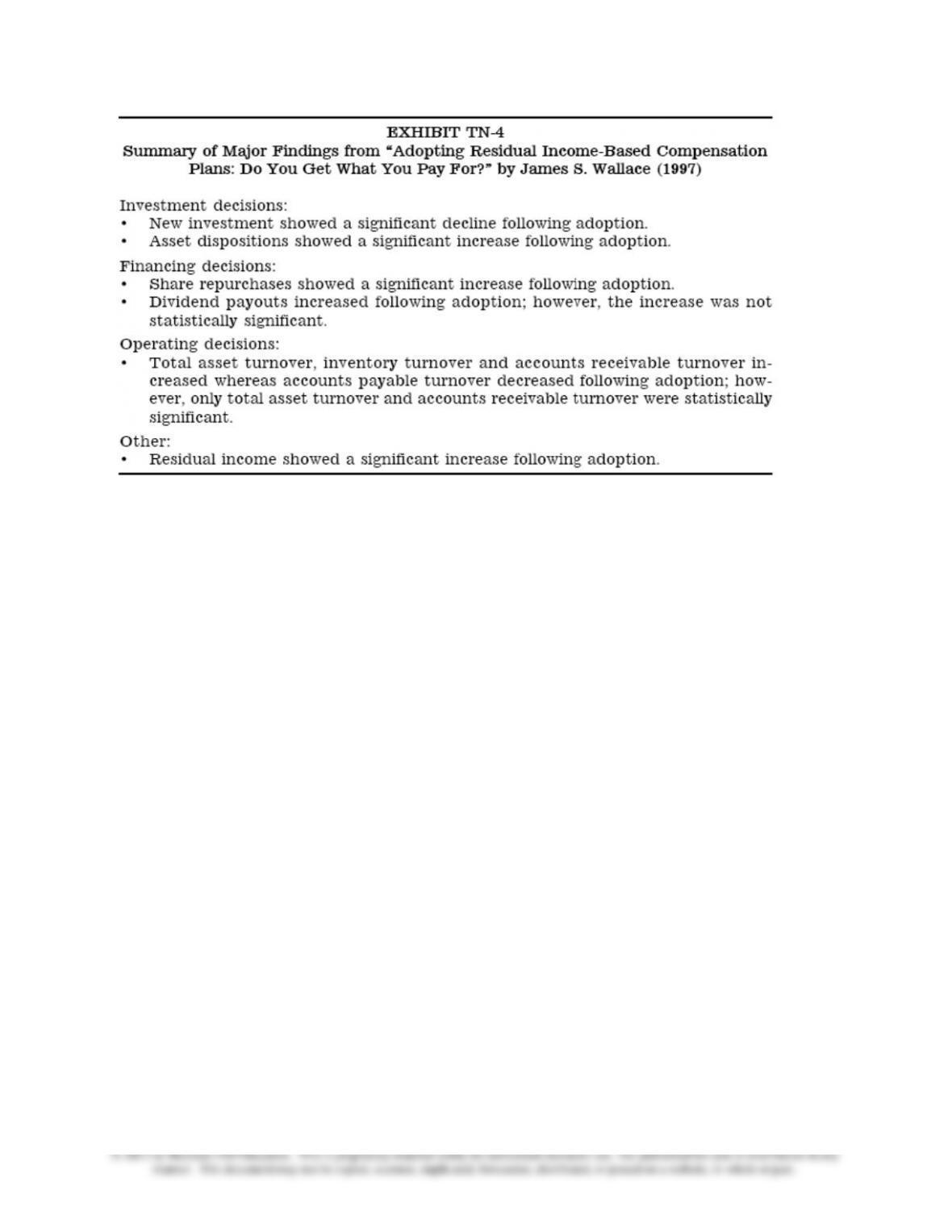

4a. If EVA® is deemed to be cost effective (and management is sure it is not the “fad of the year”),

telling shareholders about it is probably a good (but bold?) idea. Given the capital charge, EVA® will

generally be (considerably) lower than the earnings numbers shareholders are accustomed to seeing. Note

that most firms appear to start slowly with EVA®. They tend to adopt it for performance measurement

some years before explicitly incorporating the measure into management incentive compensation plans.

(Of course it is possible that all the accolades for EVA® are due to self-selection, i.e., of those firms that

consider EVA®, the only ones that adopt it are successful firms that can “afford” to take a charge for

equity capital.) Many firms now include disclosure about their use of an EVA® performance measure;

however, they do not report actual EVA® performance.

4b. Asking a CPA firm to audit the numbers could potentially represent a high cost to the firm because of

the deviations from GAAP accounting resulting from adjusting for “accounting distortions” and providing

a deduction for the cost of equity capital. These additional costs include the direct costs of the additional

work that the CPA firm must perform in order to substantiate the accounting adjustments and the

calculation of the firm’s cost of capital. In addition to the direct costs, potential indirect costs include

possible litigation costs resulting from the deviations from GAAP accounting. Zimmerman (1997) in the

Journal of Applied Corporate Finance discusses these costs. Zimmerman (1997) gives the example of a

firm that capitalizes a large amount of R&D expense, leading to high and growing EVA® and high

EVA®-based bonuses. In his example, the stock price is also rising because the market looks beyond the

GAAP numbers to the EVA® results, believing the R&D will pay off. Unfortunately in this example a

new scientific discovery destroys the usefulness of the firm’s R&D expenditures, leading to a sharp drop

in the stock price. The R&D must be written off, leading to a sharp drop in EVA®. (No adjustment is

needed for GAAP earnings since R&D is already expensed.) In retrospect, the managers received large

EVA®-based bonuses that now appear unwarranted. A potential shareholder lawsuit could result because

the large EVA®-based bonuses may appear self-serving, given that GAAP earnings were much lower all

along. Some CPA firms might relish the opportunity to work with firms that adopt EVA®. Several of the

large accounting firms currently market versions of similar shareholder value measures.

Supplemental Questions

5. Note that this question does not directly deal with the merits of EVA®. Instead it addresses the more

general topic of accounting-based vs. stock-based compensation. No, it is probably a good idea to

continue to tie at least some of the managers’ incentive compensation to accounting (or EVA®)

performance even after the stock is publicly traded (Lambert 1993, 101). A reason to have an incentive

compensation plan is to align incentives (induce effort in the interests of the owner). Use of accounting-

based compensation allows more direct monitoring of that effort. Since managers are generally less

diversified than investors, without monitoring managers will tend to adopt more conservative projects