Chapter 20 – Management Compensation, Business Analysis, and Business Valuation

increased employee tensions within some teams. For example, several instances of “parking-lot diplomacy” have been documented among

employees.

Attracting Role

Because individual compensation is highly dependent on the actions of others, John Deere may no longer attract the highest skilled workers

John Deere’s Desired Improvements in Upcoming CIPP Negotiations

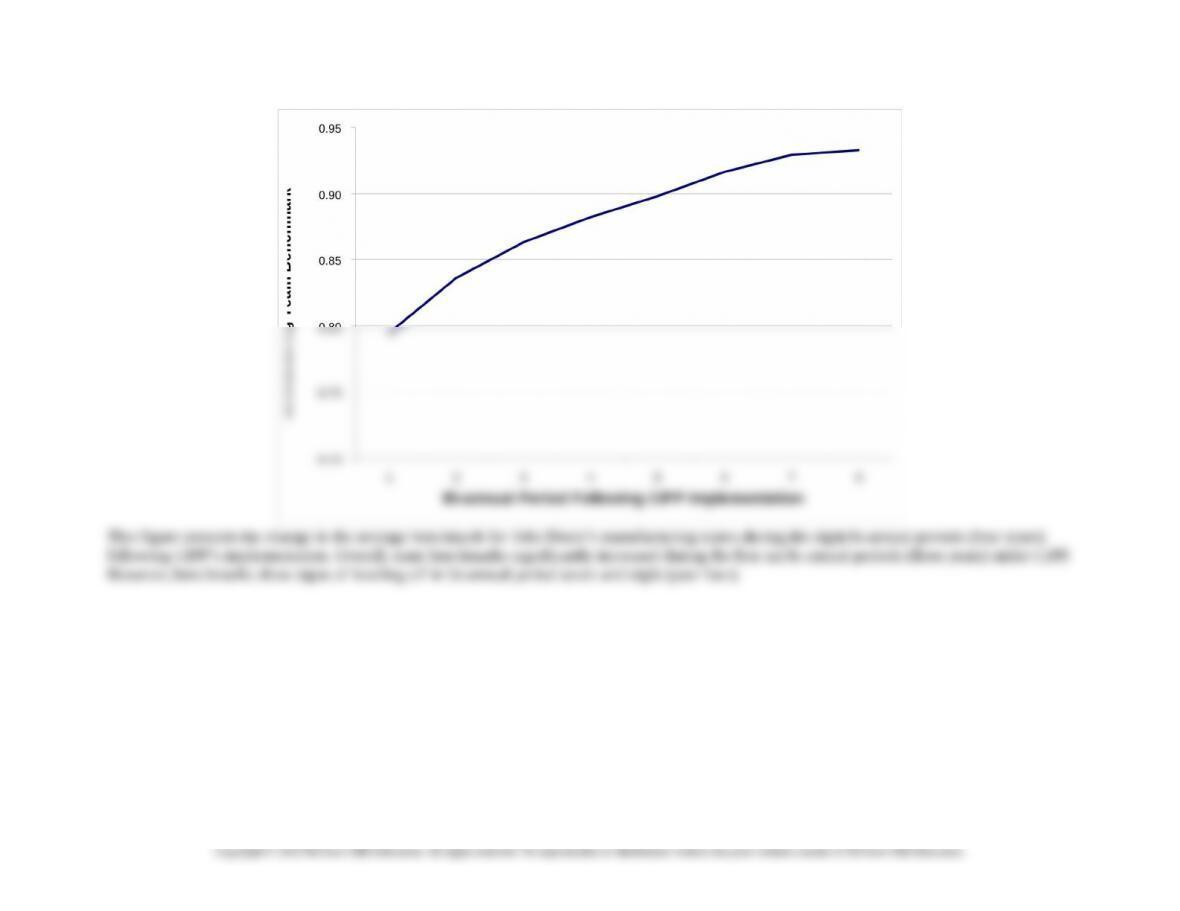

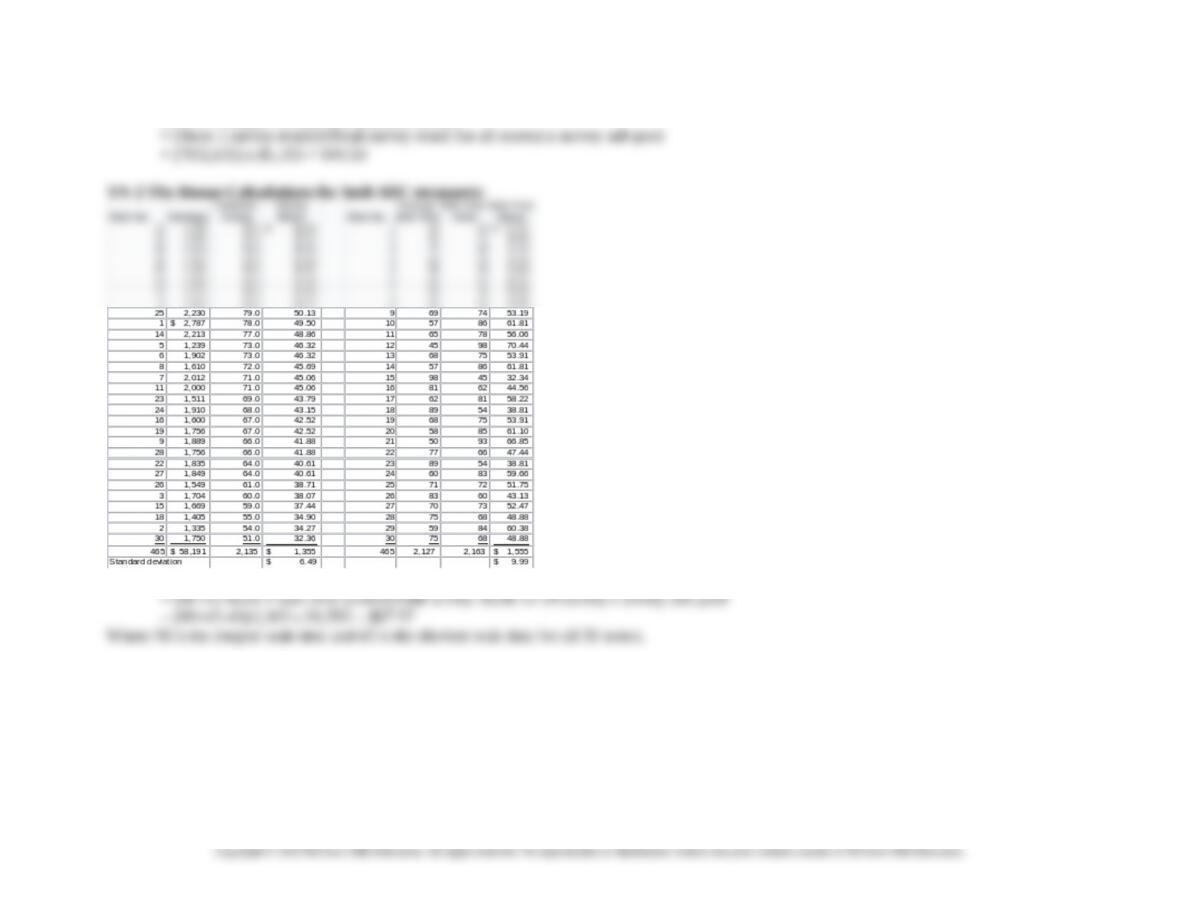

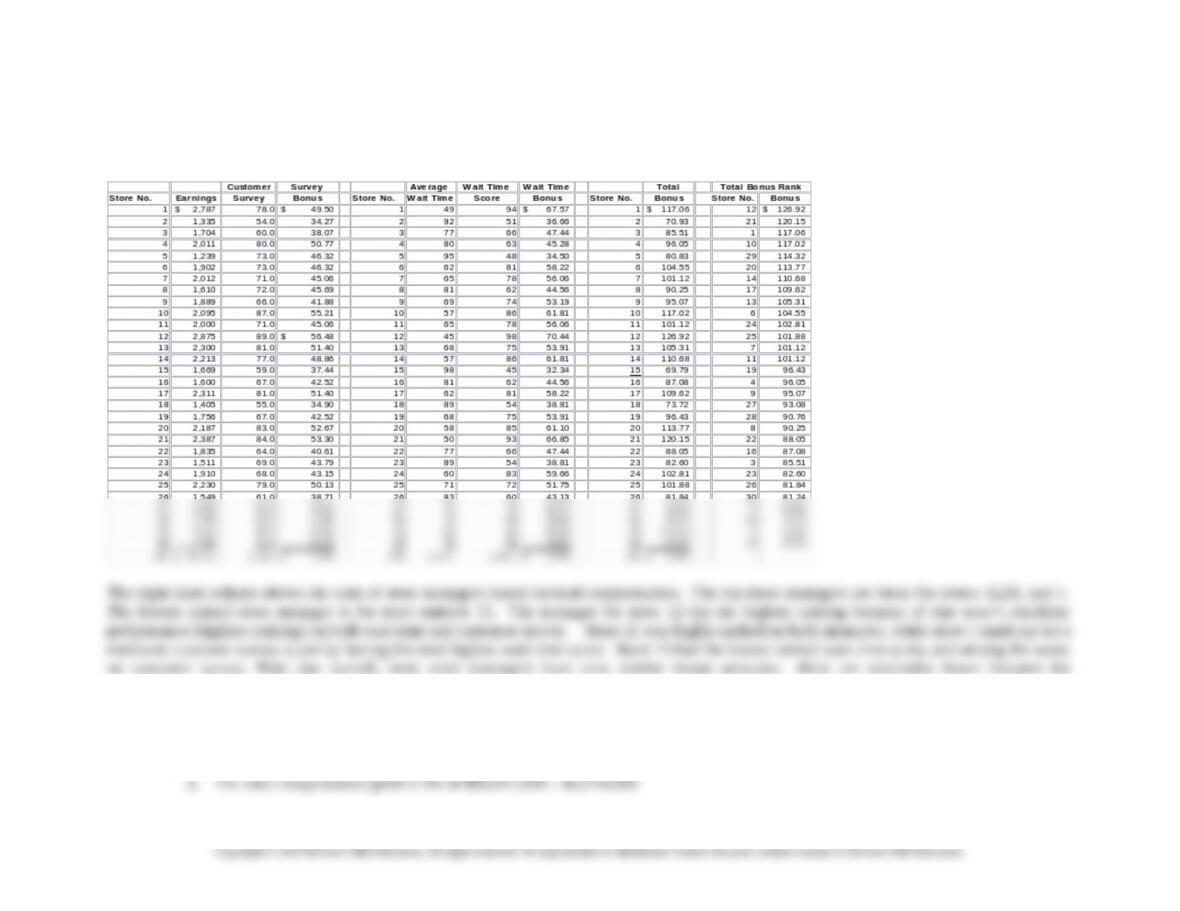

In upcoming contract negotiations, John Deere would like to improve CIPP along two dimensions. First, management would like to adjust

the benchmark whenever average bi-annual performance exceeds 115 percent rather than 120 percent. In general, this change would

decrease the benefits to employees of producing just shy of the benchmark adjustment level. Further, John Deere wants to adjust the team’s

benchmark by the exact percentage that average bi-annual performance exceeds the 115 percent threshold (as opposed to a maximum

adjustment of 6.49 percent).

This second objective reveals John Deere’s strategy for overcoming one of the inherent difficulties of CIPP – measuring the costs imposed

on the manufacturing employees of generating production efficiencies. As described in the case, implementing process improvements

potentially imposes many costs on employees (for example, reduced future compensation, greater effort, and increased probability of future

job loss). However, it is extremely difficult (if not impossible) for John Deere to accurately estimate these costs.

Since John Deere cannot perfectly measure employees’ reservation wage for these innovations, the company elected to initiate CIPP with a