Chapter 20 – Management Compensation, Business Analysis, and Business Valuation

Focusing on EVA growth provides two benefits: 1) management's attention is focused more

toward its primary responsibility increasing investor wealth; and, 2) distortions caused by using

historical cost accounting data are reduced, or eliminated. As a result, managers spend their time finding

ways to increase EVA rather than debating the intricacies of the fluctuations in the earnings reported in

their traditional accounting statements.

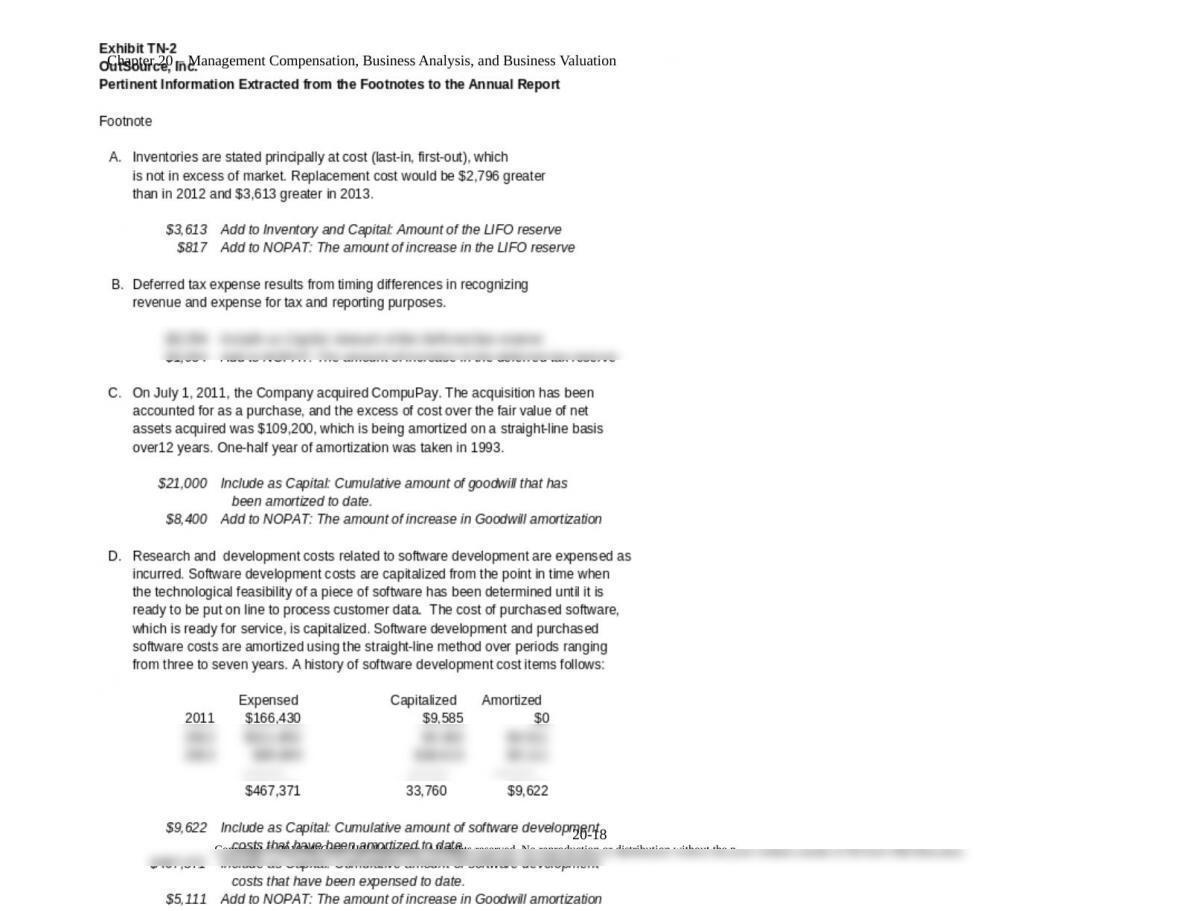

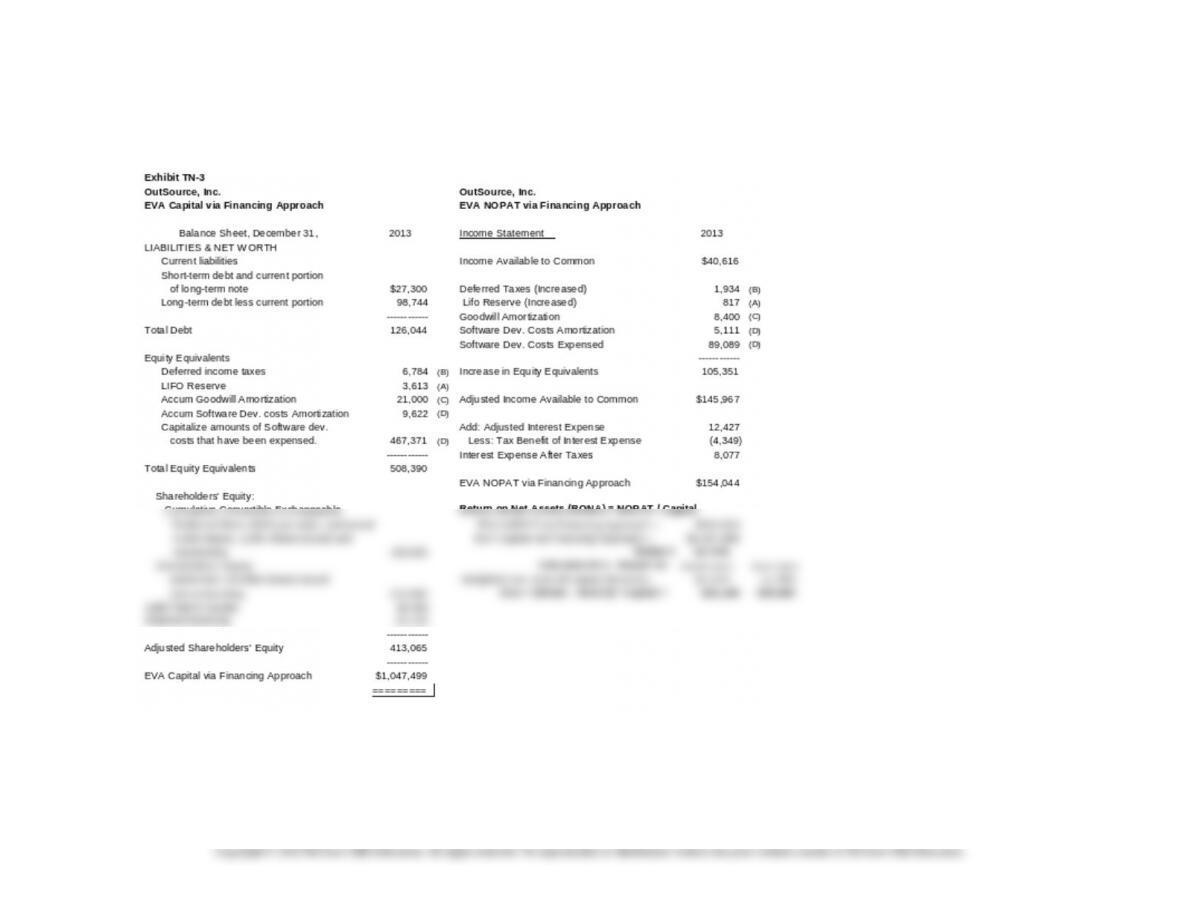

EVA measures the amount of value a firm creates during a defined period through operating

decisions it makes to increase margins, improve working capital management, efficiently using its

production facilities, redeploying underutilized assets, etc. Thus, EVA can be used to hold management

accountable for all economic outlays, whether they appear in the income statement, on the balance sheet

or in the financial statement's footnotes. EVA creates one financial statement that includes all the costs of

being in business, including the carrying cost of capital. The EVA financial statement gives managers a

complete picture of the connections among capital, margin and EVA. It makes managers conscious of

every dollar they spend, whether that dollar is spent on or off the income statement, or on operating costs

or the carrying cost of working capital and fixed assets.

Another very subtle benefit for a firm that adopts EVA is that it creates a common language for

making decisions, especially long-term decisions, resolving budgeting issues, evaluating the performance

of its organizational units and their managers, and measuring the value-creating potential of its strategic

options. An outgrowth of such an environment is that the quality of management also improves as

managers begin to think like owners and adopt a longer horizon view.

3. To this point, the emphasis has been on how focusing on EVA may help managers increase shareholder

wealth. However, for the metric to help in creating shareholder wealth, managers must behave in a

manner consistent with wealth creation. One powerful way to align managers’ interests with those of the

shareholders is to tie their compensation to output from the EVA metric. In fact, it is not just for

managers, but may be used for all employees. When implemented correctly, the basic notion of increasing

shareholder value will permeate the entire organization, and employees at all levels will then begin to act

in concert with upper levels of management.

Implementing an EVA-based incentive plan is fundamentally a process of empowerment

getting employees to be entrepreneurial, to think and act as owners, getting them to run the business as if

they owned it, and giving them a stake in the results they achieve.

The overall, firm-wide objective is to generate a persistent increase in EVA. To achieve that,

employees must understand the role they play in increasing a firm’s EVA. A key factor in sustaining a

continuing interest in EVA and in making it work is to revise the compensation system to focus on

creating value. It has been shown that one of the critical components in successfully using EVA to

improve a company's MVA is tying it to bonuses and pay schemes. Designing an incentive compensation

system that pays people for sustainable improvements in EVA, in concert with an understanding of what

drives EVA, and what drives economic returns, is what transforms behavior within a company.

A good way to get started quickly is to increase insider ownership of the firm’s stock. One way to

do this is to turn old profit-sharing plans into employee stock-ownership plans.

If an incentive system is to work, it must have certain distinctive properties:

1. An objective measure of performance, which cannot be manipulated by one of the parties who

may benefit. For example, in many existing plans, the budget is a commonly used target for

performance, but the manager being evaluated is usually heavily involved in negotiating that

budget.

2. It must be simple so that even employees far down in the organization will understand how EVA

is tied to economic value and can follow it well.

3. Bonus amounts have to be significant enough in amount for employees to alter their behaviors.

20-16

Education.