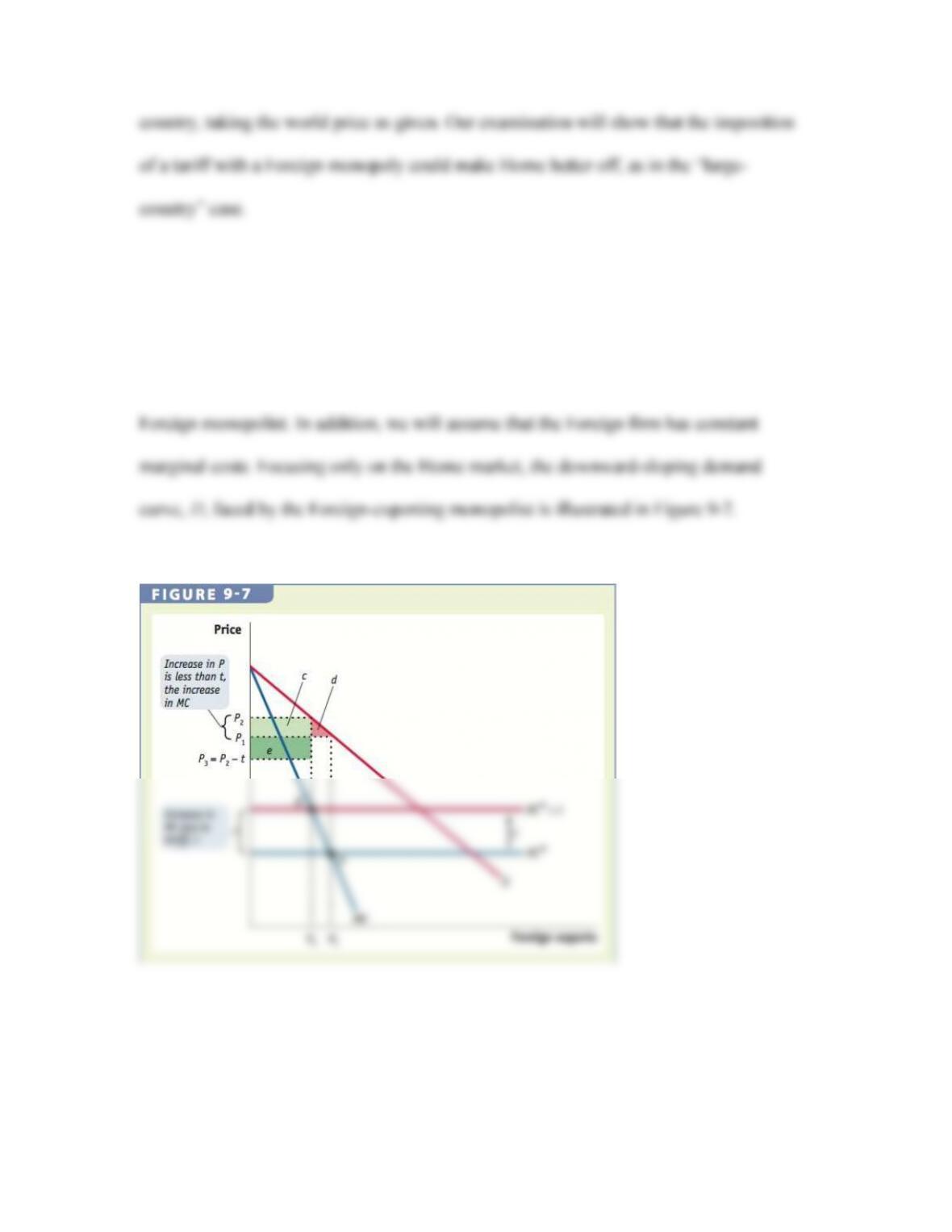

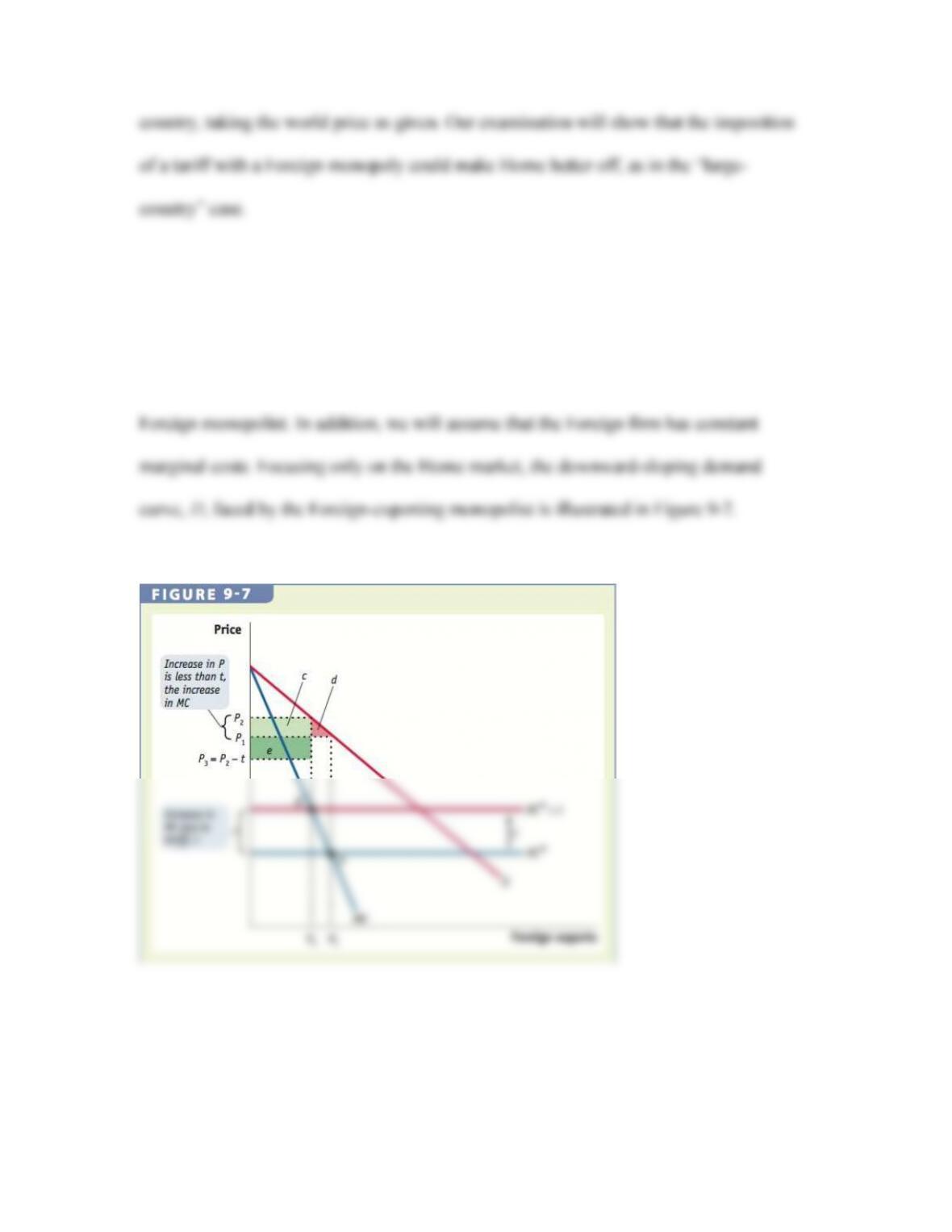

Effect of a Tariff on Home Price With the fixed tariff in the amount of t dollars, the

marginal cost of exporting to the Home market increases to MC* + t, as shown in Figure

9-7. Given the higher marginal costs, the Foreign firm decreases exports to X2. This

In situations in which the marginal revenue curve is steeper than the Home country’s

demand curve, the importing country may experience a terms-of-trade gain because the

increase in the import price from P1 to P2 is less than the amount of the tariff, t. To

prevent the quantity exported from falling below X2, the Foreign firm absorbs part of the

Effect of the Tariff on Home Welfare To determine the effect of the tariff on Home

welfare, note that the increase in the import price reduces consumer surplus by the area (c

+ d), as illustrated in Figure 9-7. Home producer surplus is unaffected, as there are no