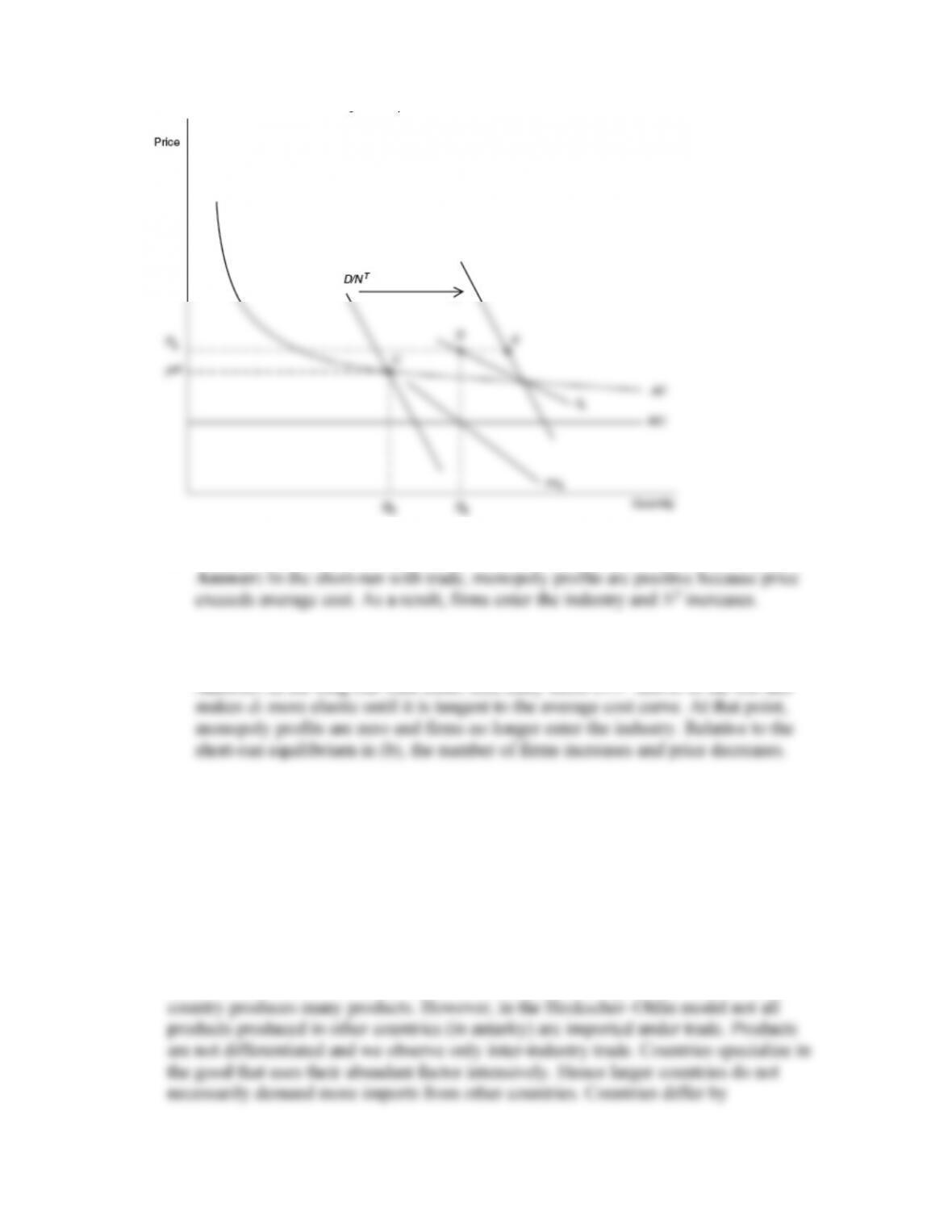

a. Compared with the no-trade equilibrium, how much does industry demand D

increase? How much does the number of firms (or product varieties) increase?

Does the demand curve D/NA still apply after the opening of trade? Explain why

or why not.

b. Does the d1 curve shift or pivot due to the opening of trade? Explain why or why

not.

Answer: Because D/NA is unchanged, point A is still on the short-run demand

c. Compare your answer to (b) with the case in which Home trades with only one

other identical country. Specifically, compare the elasticity of the demand curve

d1 in the two cases.

Answer: In the case with three countries, Home consumers have more varieties to

d. Illustrate the long-run equilibrium with trade, and compare it with the long-run

equilibrium when Home trades with only one other identical country.

Answer: The long-run equilibrium with trade occurs where the demand curve

5. Starting from the long-run trade equilibrium in the monopolistic competition model,

as illustrated in Figure 6-7, consider what happens when industry demand D

increases. For instance, suppose that this is the market for cars, and lower gasoline

prices generate higher demand D.

a. Redraw Figure 6-7 for the Home market and show the shift in the D/NT curve and

the new short-run equilibrium.