14 Krugman/Obstfeld/Melitz • International Economics: Theory & Policy, Tenth Edition

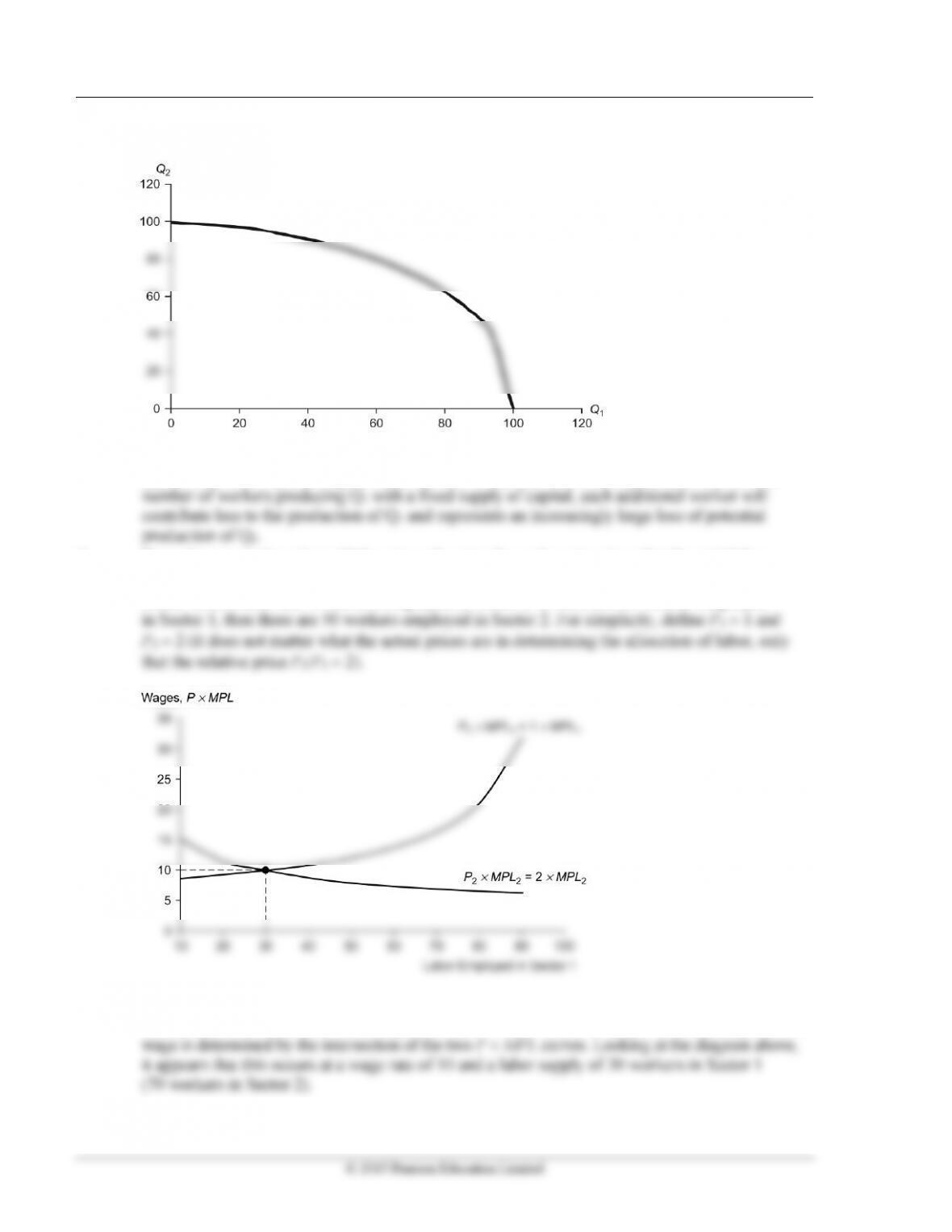

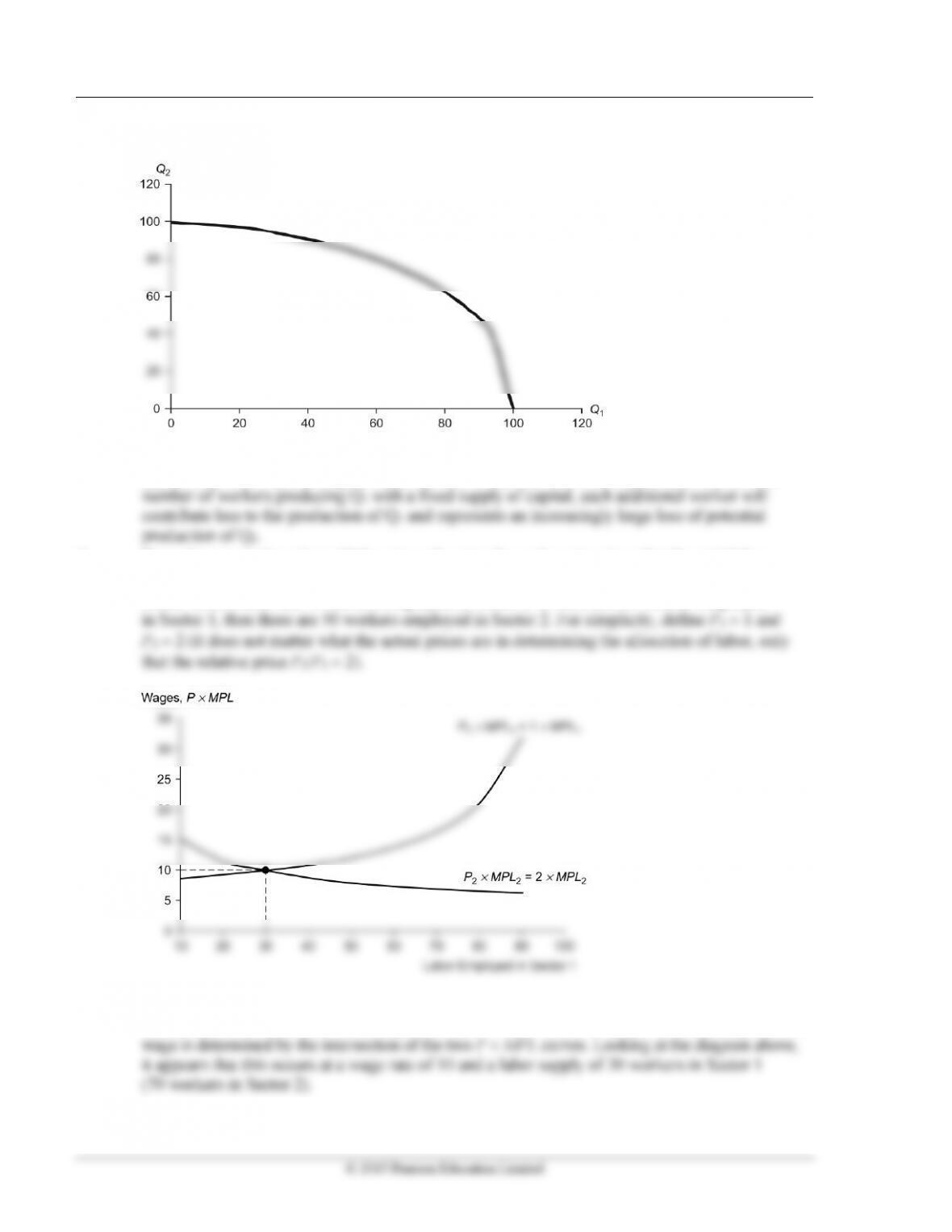

Food is produced using labor and its specific factor, land. Given that capital and labor are specific to their

respective industries, the mix of goods produced by a country is determined by share of labor employed in

each industry. The key difference between the Ricardian model and the Specific Factors model is that in the

latter, there are diminishing returns to labor. For example, production of food will increase as labor is added,

but given a fixed amount of land, each additional worker will add less and less to food production.

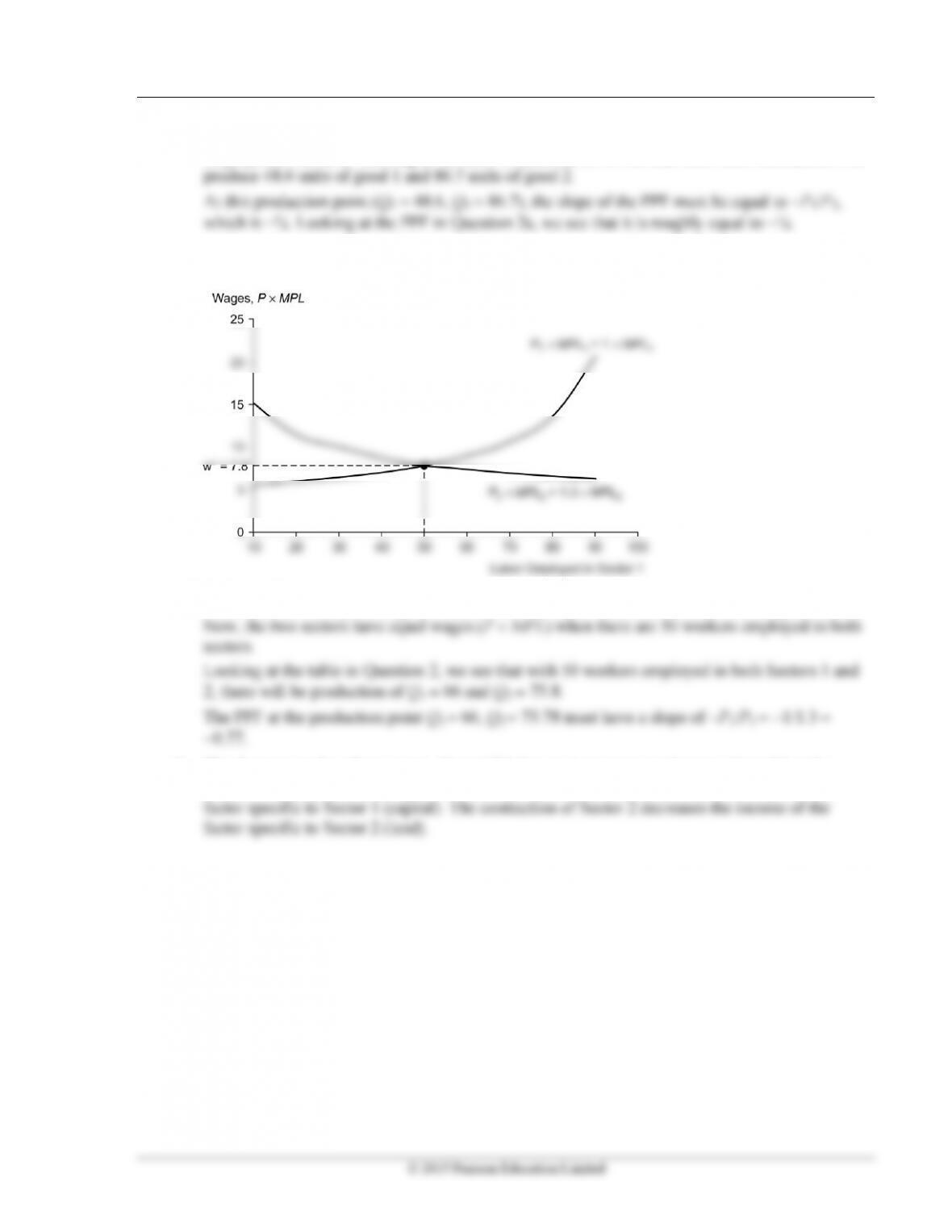

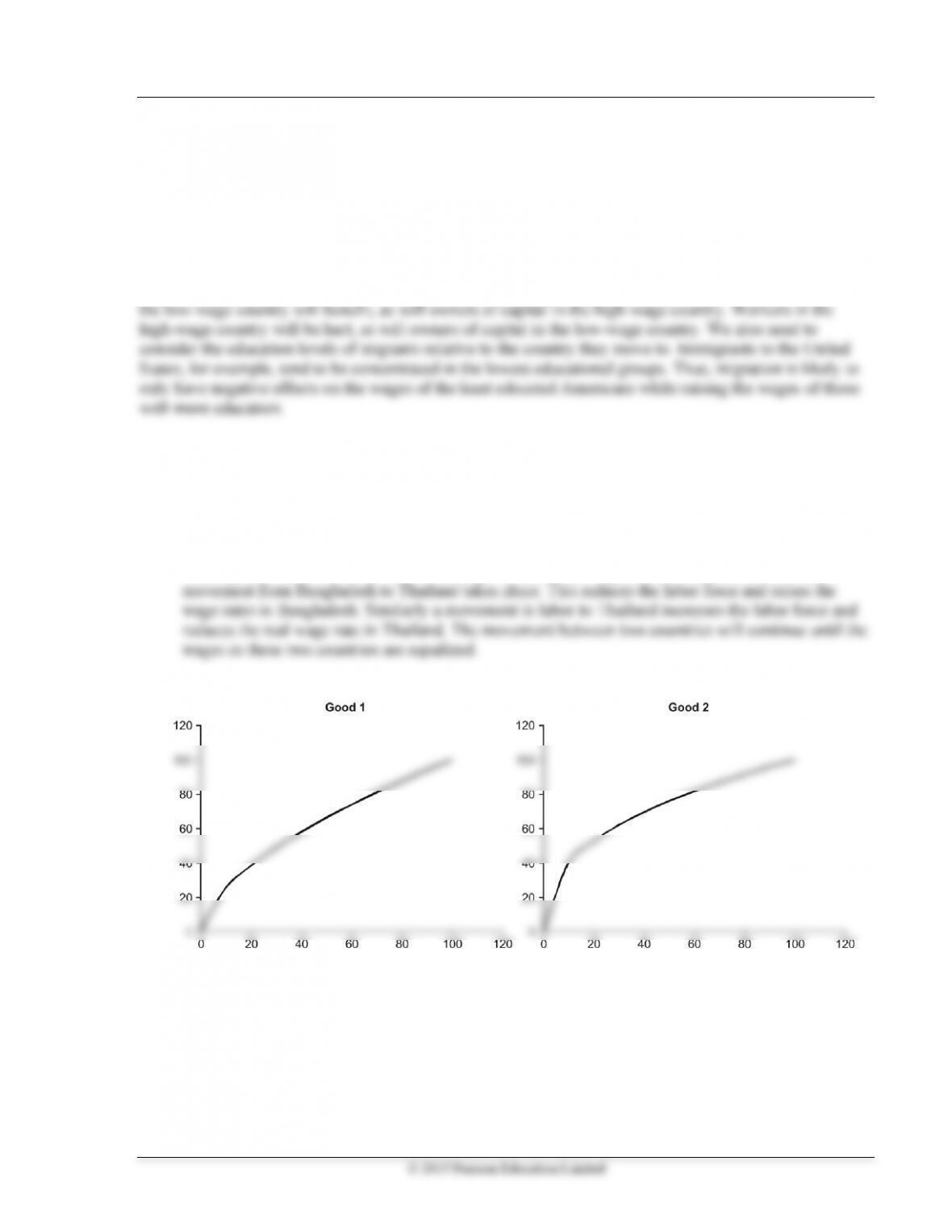

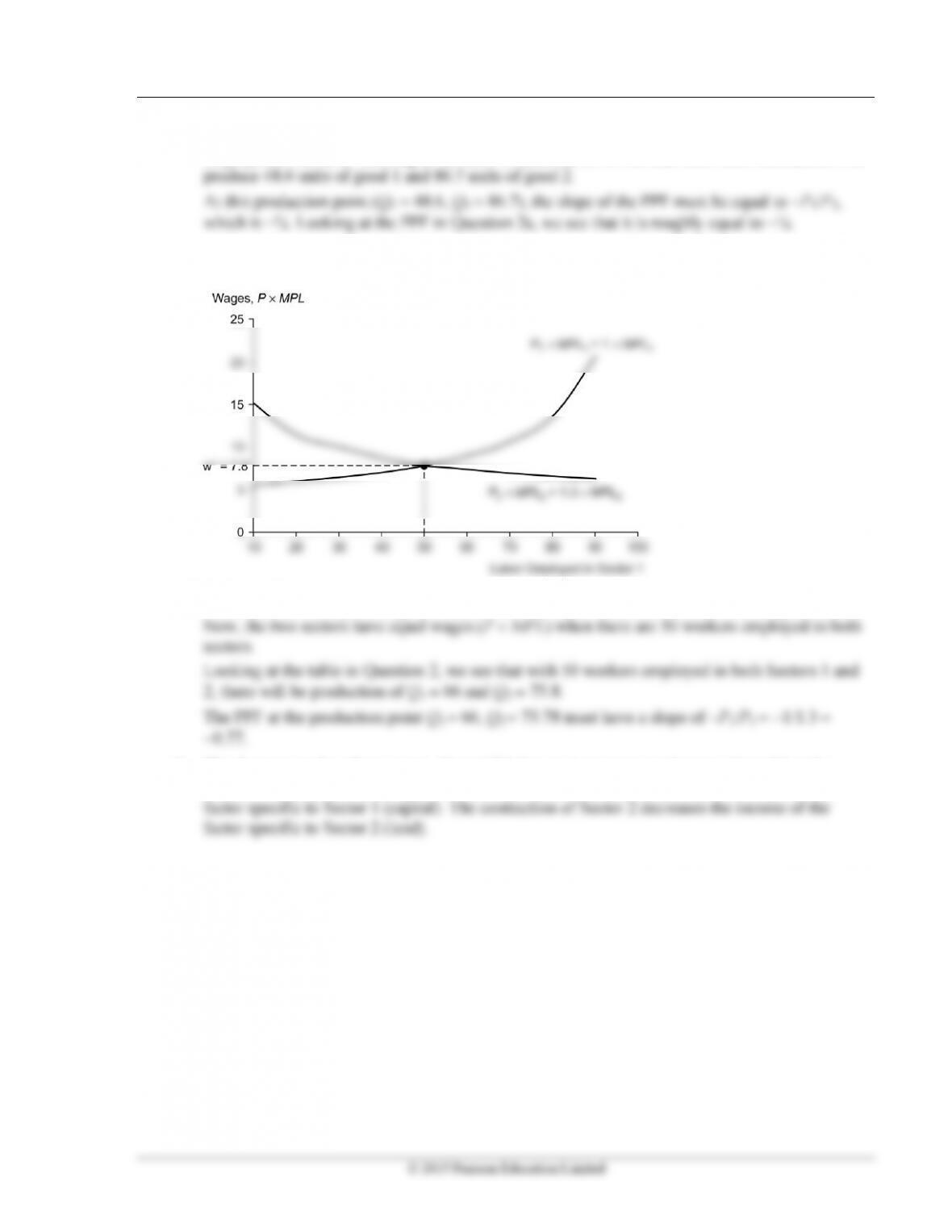

As we assume that labor is perfectly mobile between industries, the wage rate must be identical between

industries. With competitive labor markets, the wage must be equal to the price of each good times the

marginal product of labor in that sector. We can use the common wage rate to show that the economy will

produce a mix of goods such that the relative price of one good in terms of the other is equal to the relative

cost of that good in terms of the other. Thus, an increase in the relative price of one good will cause the

economy to shift its production toward that good.

With international trade, the country will export the good whose relative price is below the world relative

price. The world relative price may differ from the domestic price before trade for two reasons. First, as in

the Ricardian model, countries differ in their production technologies. Second, countries differ in terms of

their endowments of the factors specific to each industry. After trade, the domestic relative price will equal

the world relative price. As a result, the relative price in the exporting sector will rise, and the relative

price in the import competing sector will fall. This will lead to an expansion in the export sector and a

contraction of the import competing sector.

Suppose that after trade, the relative price of cloth increases by 10 percent. As a result, the country will

increase production of cloth. This will lead to a less than 10 percent increase in the wage rate because

some workers will move from the food to the cloth industry. The real wage paid to workers in terms of

cloth (w/PC) will fall, while the real wage paid in terms of food (w/PF) will rise. The net welfare effect for

labor is ambiguous and depends on relative preferences for cloth and food. Owners of capital will

unambiguously gain because they pay their workers a lower real wage, while owners of land will

Given these positive net welfare effects, why is there such opposition to free trade? To answer this question,

the chapter looks at the political economy of protectionism. The basic intuition is that the though the total

gains exceed the losses from trade, the losses from trade tend to be concentrated, while the gains are diffused.

Import tariffs on sugar in the United States are used to illustrate this dynamic. It is estimated that sugar tariffs

cost the average person $7 per year. Added up across all people, this is a very large loss from protectionism,

but the individual losses are not large enough to induce people to lobby for an end to these tariffs. However,

the gains from protectionism are concentrated among a small number of sugar producers, who are able to

effectively coordinate and lobby for continued protection. When the losses from trade are concentrated

among politically influential groups, import tariffs are likely to be seen. Ohio, a key swing state in U.S.

presidential elections and a major producer of both steel and tires, is used as an example to illustrate this

point with both Presidents Bush and Obama supporting tariffs on steel and tires, respectively.

Although the losers from trade are often able to successfully lobby for protectionism, the chapter

highlights three reasons why this is an inefficient method of limiting the losses from trade. First, the actual

impact of trade on unemployment is fairly low, with estimates of only 2.5 percent of unemployment

directly attributable to international trade. Second, the losses from trade are driven by one industry