8 Krugman/Obstfeld/Melitz • International Economics: Theory & Policy, Tenth Edition

◼ Chapter Overview

The Ricardian model provides an introduction to international trade theory. This most basic model of

trade involves two countries, two goods, and one factor of production, labor. Differences in relative labor

productivity across countries give rise to international trade. This Ricardian model, simple as it is, generates

important insights concerning comparative advantage and the gains from trade. These insights are necessary

foundations for the more complex models presented in later chapters.

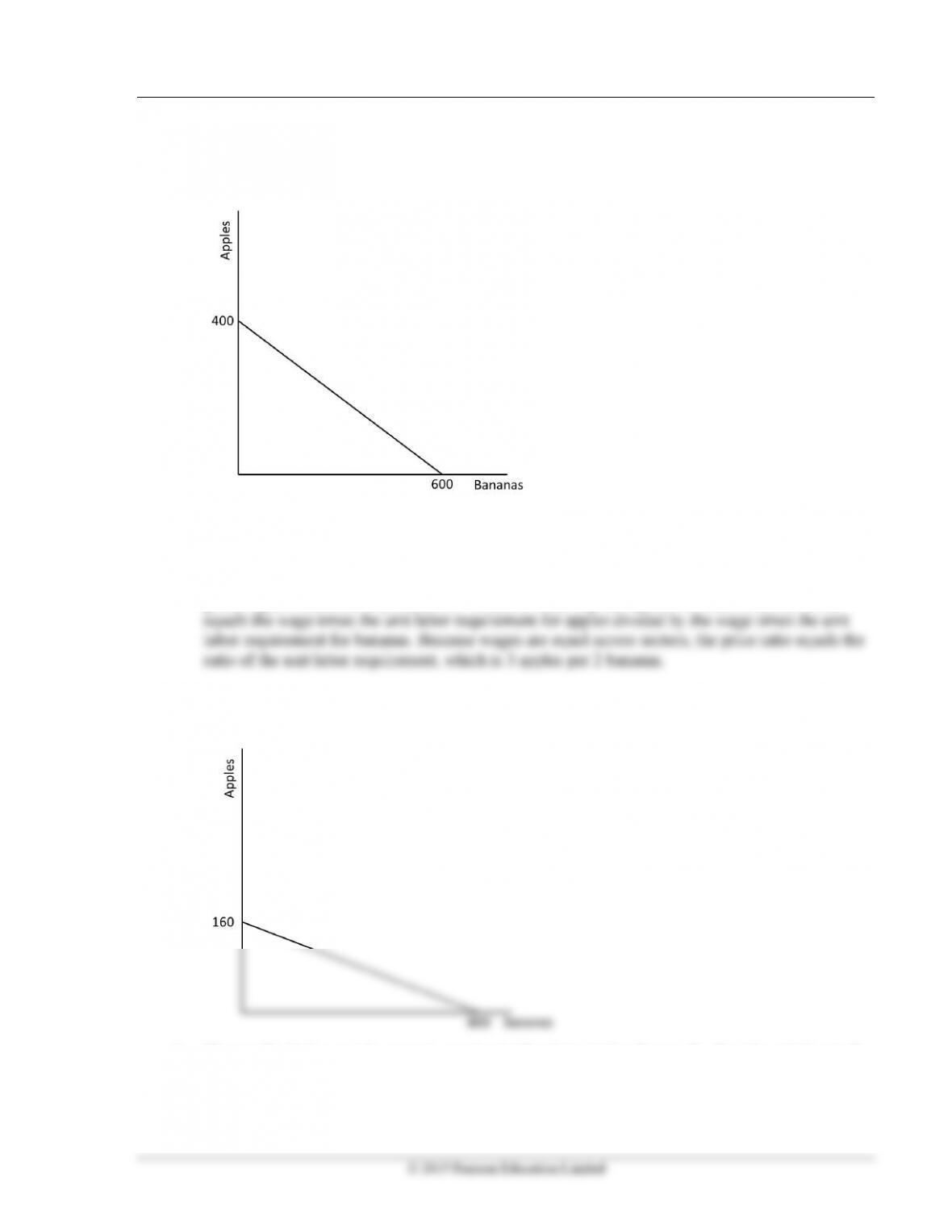

The text exposition begins with the examination of the production possibility frontier and the relative prices

of goods for one country. The production possibility frontier is linear because of the assumption of constant

returns to scale for labor, the sole factor of production. The opportunity cost of one good in terms of the other

equals the price ratio because prices equal costs, costs equal unit labor requirements times wages, and

wages are equal in each industry.

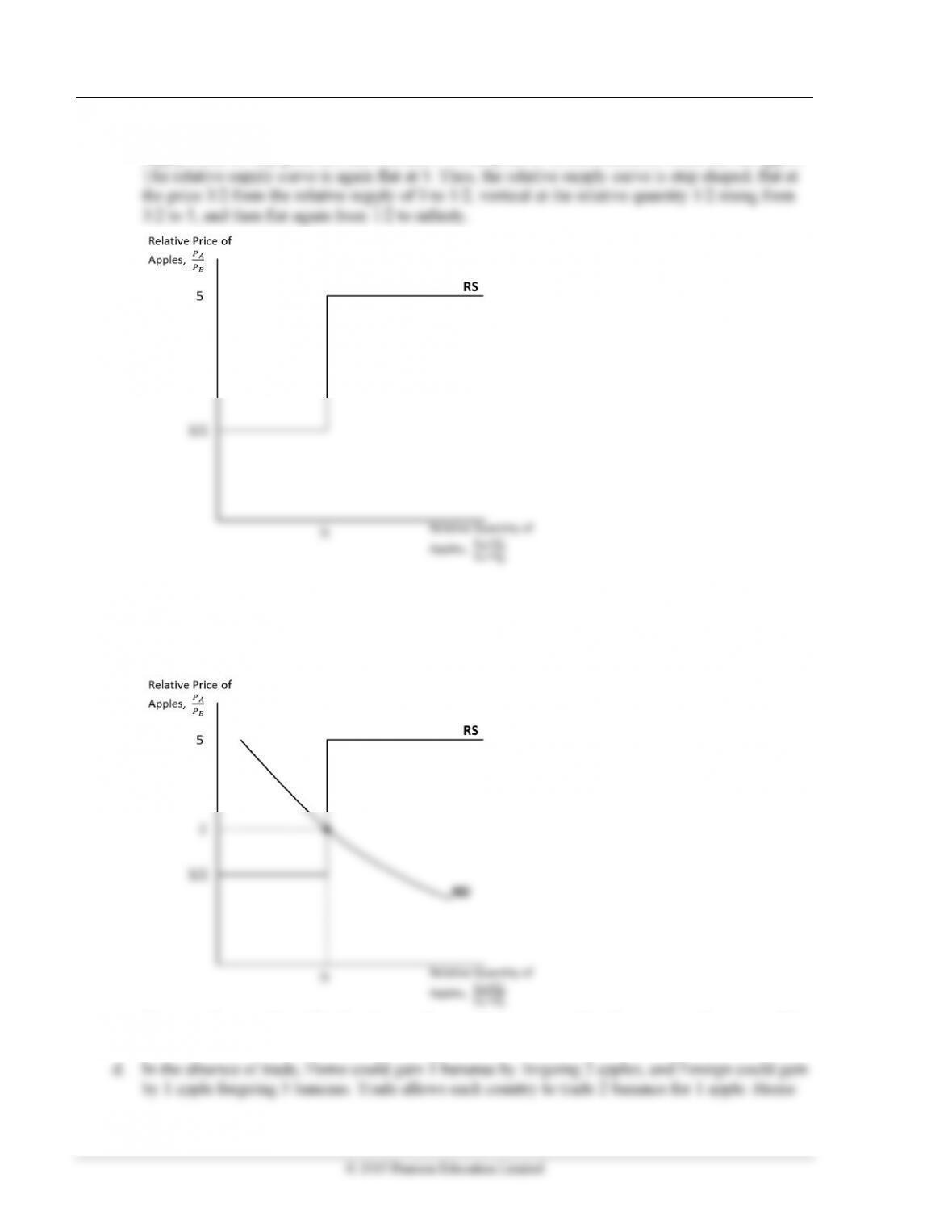

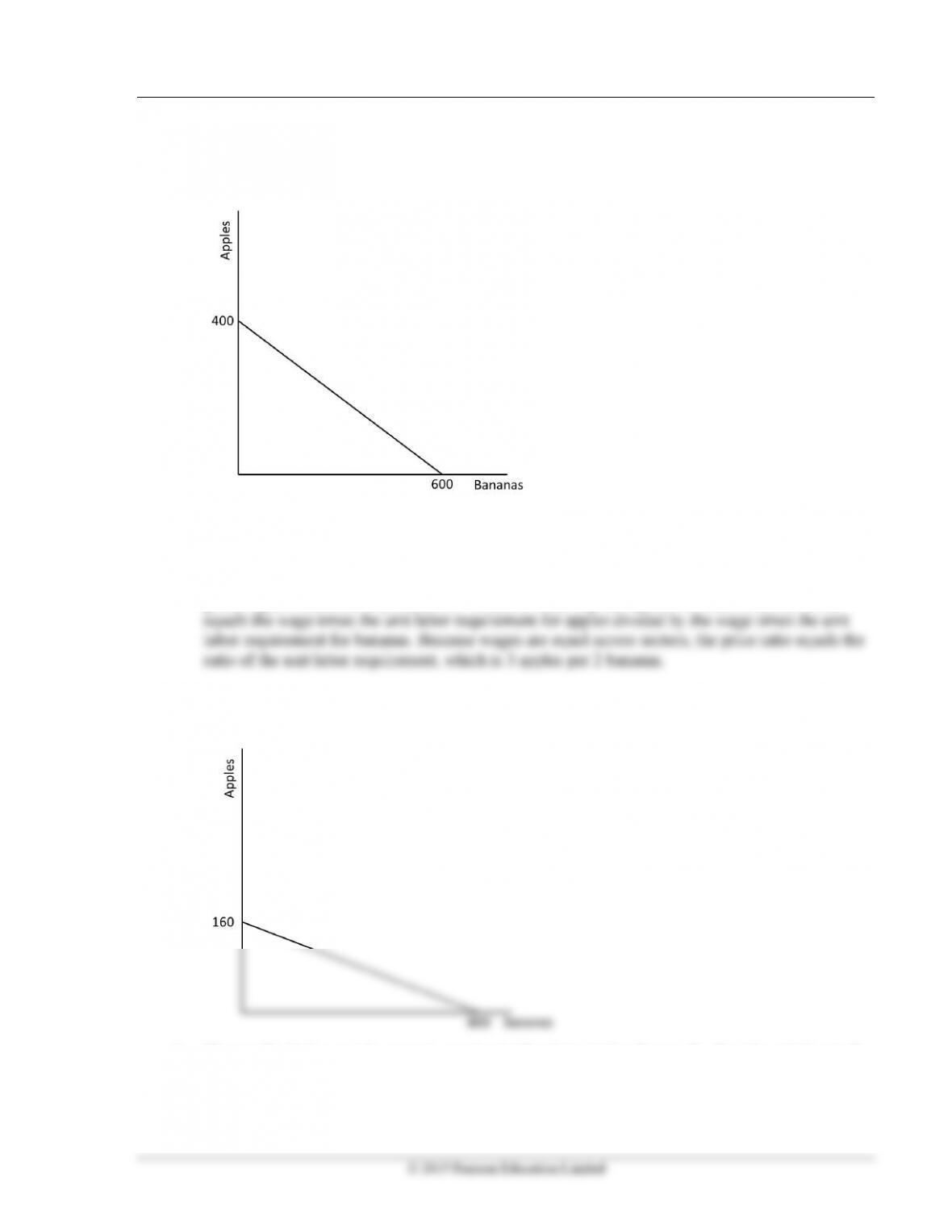

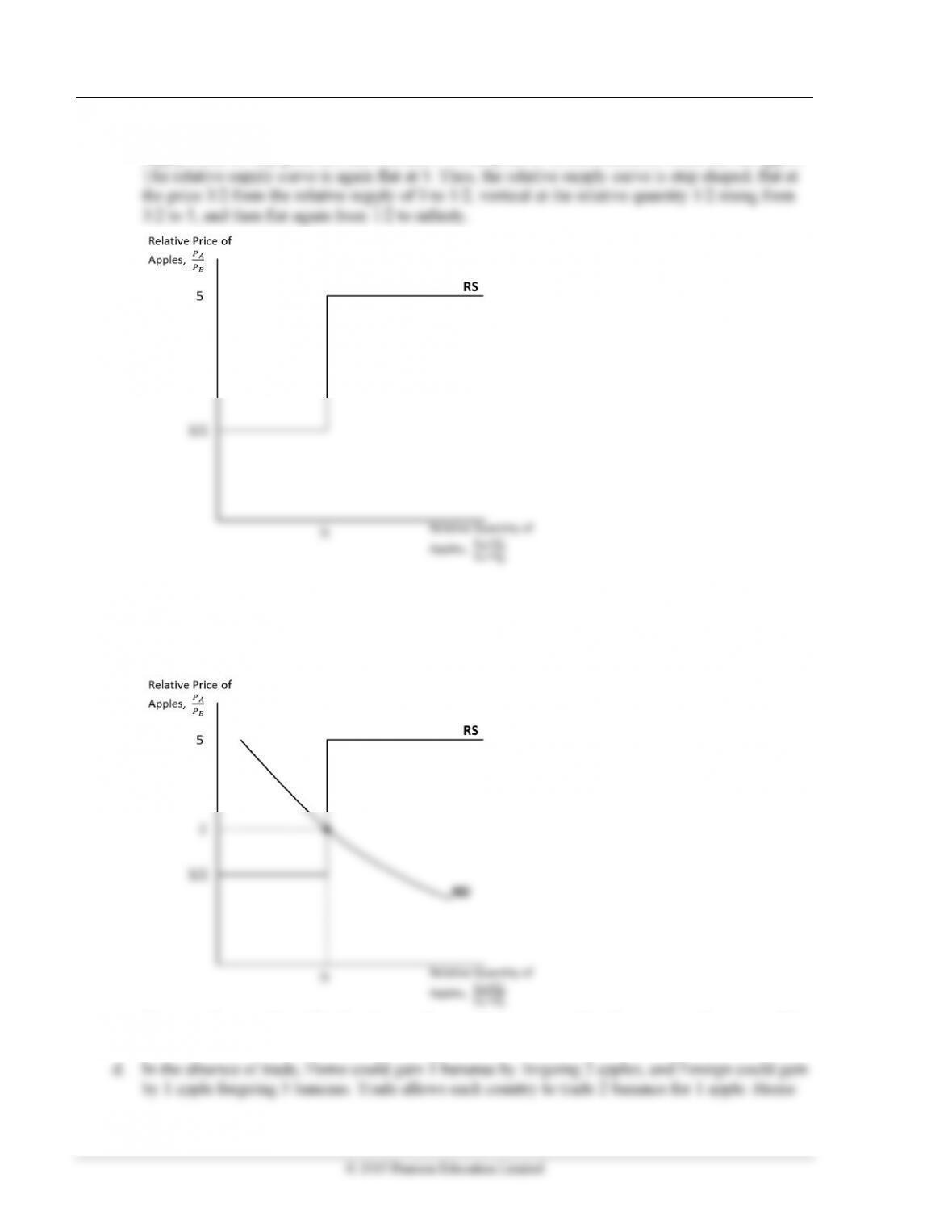

After defining these concepts for a single country, a second country is introduced that has different relative

unit labor requirements. Supply and demand curves relative to general equilibrium are developed. This

analysis demonstrates that at least one country will specialize in production. The gains from trade are then

demonstrated with a graph and a numerical example. The intuition of indirect production, that is

“producing” a good by producing the good for which a country enjoys a comparative advantage and then

trading for the other good, is an appealing concept to emphasize when presenting the gains from trade

argument. Students are able to apply the Ricardian theory of comparative advantage to analyze three

misconceptions about the advantages of free trade. Each of the three “myths” represents a common

argument against free trade, and the flaws of each can be demonstrated in the context of examples already

Although the initial intuitions are developed in the context of a two-good model, it is straightforward to

extend the model to describe trade patterns when there are N goods. Comparative advantage in this model is

driven by relative wages between countries rather than relative prices. However, the implication that

countries will export goods for which they have the lowest opportunity cost remains.

The N-good model is used to discuss the role that transport costs play in making some goods nontraded.

As transport costs rise, the gains from trade decrease, and in some cases they are completely eliminated.

The chapter ends with a discussion of empirical evidence of the Ricardian model. The authors are careful

to point out that, while the rather simplified model cannot explain all trade patterns, the basic prediction that

countries tend to export goods for which they have a comparative advantage (high relative productivity)

has been confirmed by a number of studies.