Chapter 22 (11) Developing Countries: Growth, Crisis, and Reform 143

Developing countries have defaulted in many situations over time, from 19th-century American states to

most developing countries in the Depression to the debt crisis in the 1980s. If lenders lose confidence,

they may refuse further lending, forcing developing countries to bring their current account into balance.

These crises are driven by similar self-fulfilling mechanisms as exchange rate crises or bank runs (and are

often referred to as “sudden stops” when financial flows stop running to developing countries seemingly

without warning), and the discussion of debt default provides an opportunity to revisit the ideas of

currency crises and bank runs before a full-fledged discussion of the East Asian crisis.

It is important to recognize the different types of financing available to countries. Bond funding, bank

borrowing, or official lending can all provide debt-oriented funding, while foreign direct investment or

portfolio investment in firms can provide equity financing. In addition, countries can borrow in their own

currency or in another currency. The chapter discusses the problem of “original sin” where many countries

are unable to borrow in their own currency due to both problems in global capital markets and countries’

own histories of poor economic policies.

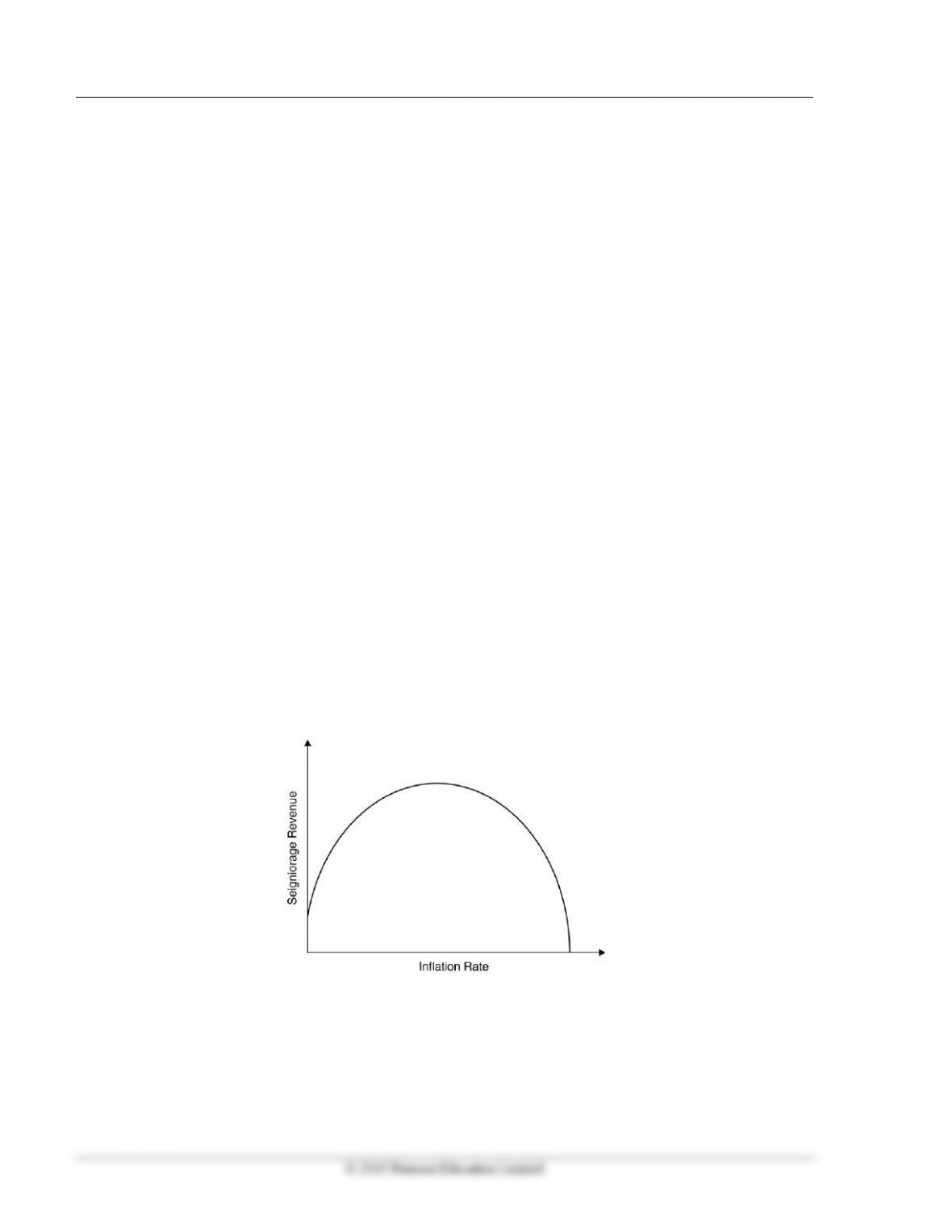

The next section of the chapter focuses on the experiences of Latin America. In the 1970s, inflation became

a widespread problem in Latin America, and many countries tried using a tablita, or crawling peg. The

strategy, though, did not stop inflation, and large real appreciations were the result. Government-guaranteed

loans were widespread, leading to moral hazard. By the early 1980s, collapsing commodity prices, a rising

dollar, and high U.S. interest rates precipitated default in Mexico followed by other developing countries.

After the debt crisis stretched through most of the decade and slowed developing country growth in many

regions, debt renegotiations finally loosened burdens on many countries by the early 1990s.

After the debt crisis appeared to be ending, capital began to flow back into many developing countries.

These countries were finally undertaking serious economic reform to stabilize their economy. The chapter

details these efforts in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico and also discusses how crisis unfortunately

returned to some of these countries.

A case study box on international reserves and China addresses two connected issues that are often

controversial politically: the mass accumulation of international reserves (largely in the form of U.S.

Treasury Bills) by developing countries and the attempt by China to limit the appreciation of its currency.

The box points out that much of the reserves accumulation is connected to insuring against shifts in financial

flows (such as sudden stops of external financing) more than trying to insure against excess needs based

on trade flows (as was the case when financial flows were quite small). In addition to self-insurance, though,

some of the reserves accumulation is a by-product of sterilized intervention. The clearest example of this is

China. China has tried to limit appreciation of its currency to encourage export-led growth. This is done in

part with capital controls, but also through purchasing dollars and selling yuan to prop up the value of the

dollar. As we know from the II-XX model in Chapter 19 (8), at some point, China will likely need to

appreciate or experience inflation. Since 2005, China’s currency has gradually appreciated, gaining about

13 percent in value by January 2008. China repegged its currency in the midst of the 2008 financial crisis,

but then announced in June 2010 (partially in response to foreign pressure) that it would adopt a “managed

float” for its currency. Since that announcement, the yuan has appreciated by another 10 percent. The

experiences outlined in this chapter emphasize the policy trilemma discussed in Chapter 19 (8) and led to

calls for reform of the world’s financial architecture. The chapter next considers some of these, from