120 Krugman/Obstfeld/Melitz • International Economics: Theory & Policy, Tenth Edition

in a futile effort to stimulate domestic economic growth during the Great Depression. These beggar-thy-

neighbor policies provoked foreign retaliation and led to the disintegration of the world economy. As one

of the case studies shows, strict adherence to the gold standard appears to have hurt many countries during

the Great Depression.

Determined to avoid repeating the mistakes of the interwar years, Allied economic policy makers met at

Bretton Woods in 1944 to forge a new international monetary system for the postwar world. The

exchange-rate regime that emerged from this conference had at its center the U.S. dollar. All other

currencies had fixed exchange rates against the dollar, which itself had a fixed value in terms of gold. An

International Monetary Fund was set up to oversee the system and facilitate its functioning by lending to

countries with temporary balance of payments problems.

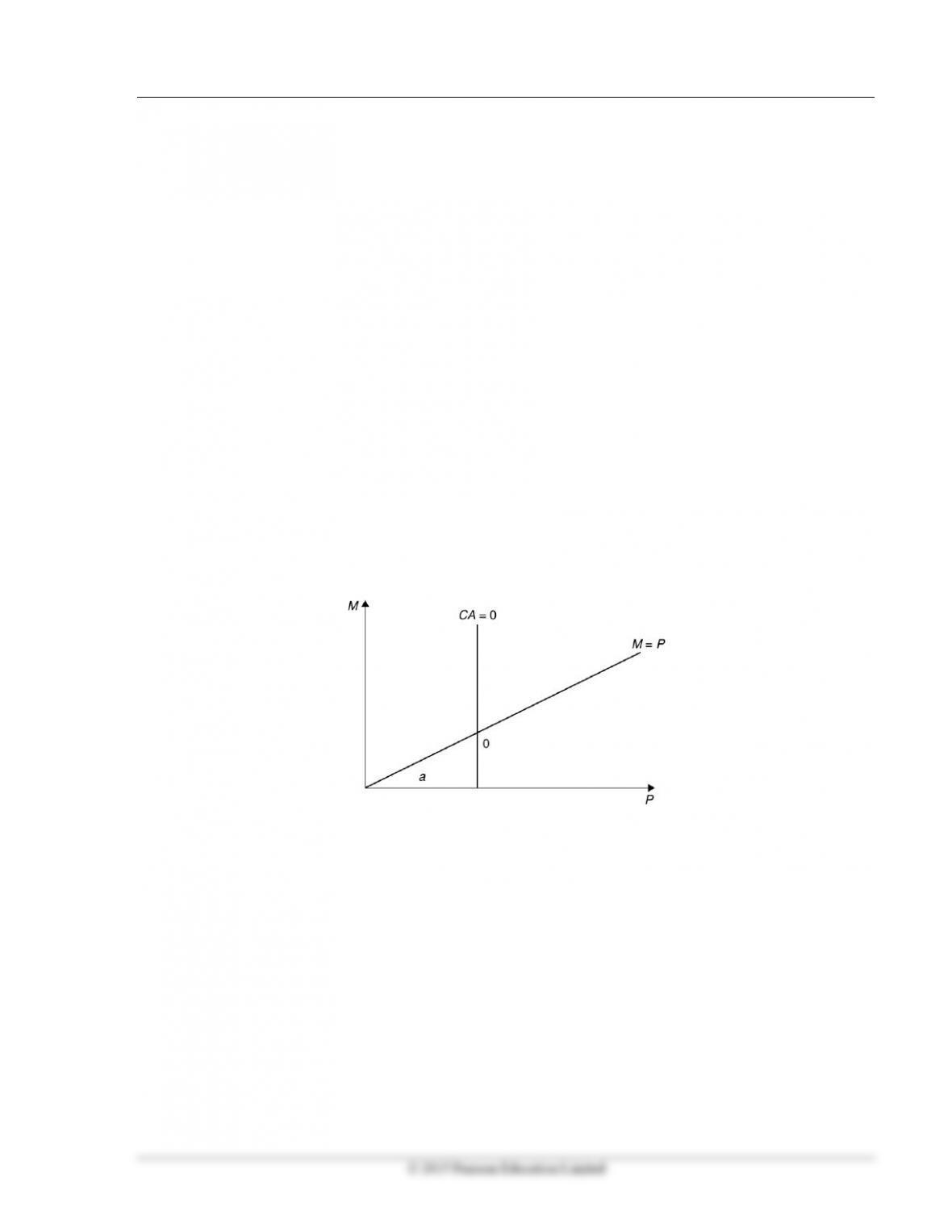

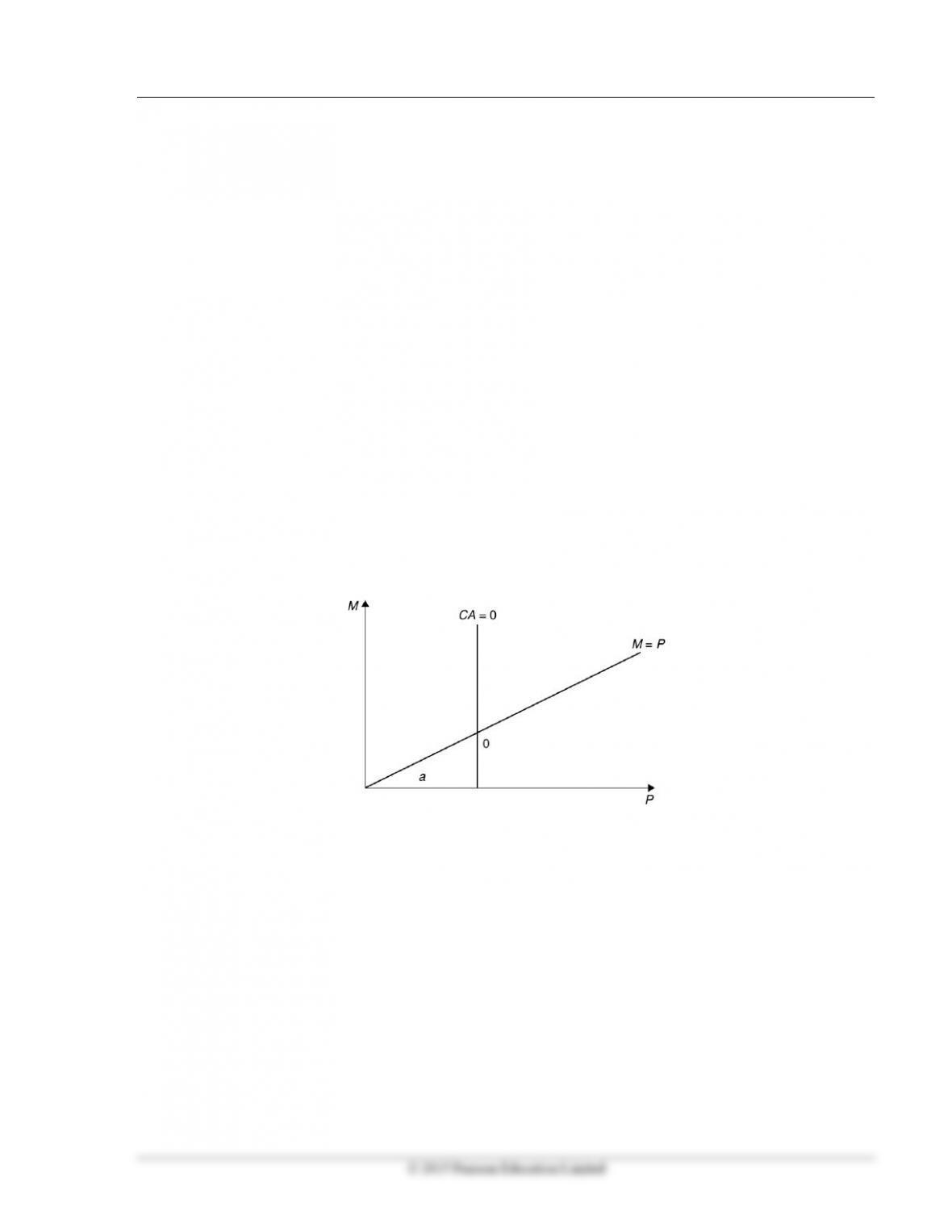

A formal discussion of internal and external balance introduces the concepts of expenditure-switching and

expenditure-changing policies. The Bretton Woods system, with its emphasis on infrequent adjustment

of fixed parities, restricted the use of expenditure-switching policies. Increases in U.S. monetary growth to

finance fiscal expenditures after the mid-1960s led to a loss of confidence in the dollar and the termination

of the dollar’s convertibility into gold. The analysis presented in the text demonstrates how the Bretton

Woods system forced countries to “import” inflation from the United States and shows that the breakdown

of the system occurred when countries were no longer willing to accept this burden.

Following the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system, many countries moved toward floating exchange

rates. In theory, floating exchange rates have four key advantages: They allow for independent monetary

policy; they are symmetric in terms of the costs of adjustment faced by deficit and surplus countries; they

act as automatic stabilizers that mitigate the effects of economic shocks; and they help maintain external

balance through stabilizing speculation that depreciates the currency of a country with a large current-

account deficit.

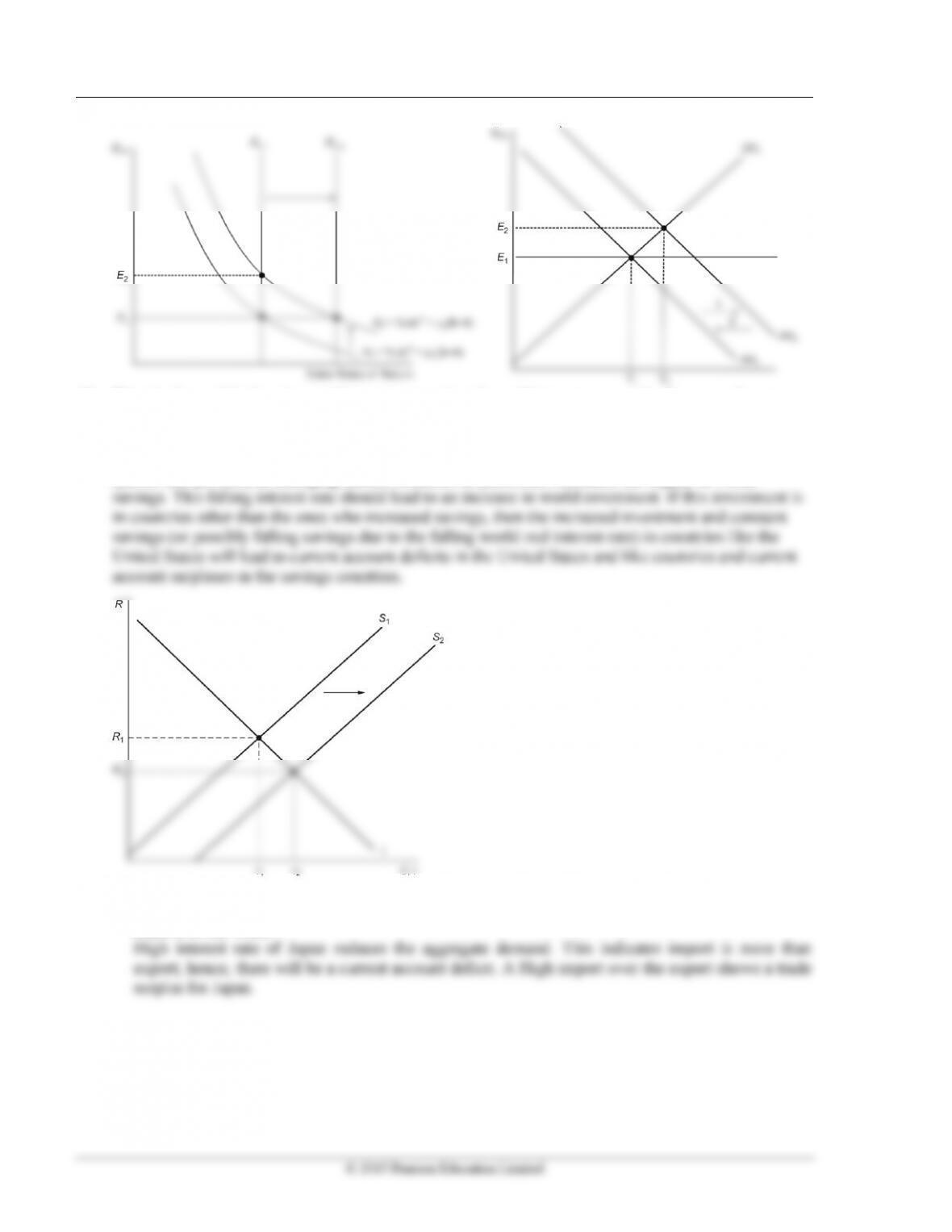

These advantages must be matched with the experience of countries running floating exchange rate regimes.

Floating exchange rates should give countries greater autonomy over monetary policy. However, the

evidence suggests that changes in monetary policy in one country do get transmitted across borders,

limiting autonomy. Second, exchange rates have become less stable. For example, in the mid 1970s, the

United States chose to pursue monetary expansion to fight a recession, whereas Germany and Japan

contracted their money supplies to counter inflation. As a result, the dollar sharply depreciated against these

currencies. The symmetry benefit of floating rates is also limited by the fact that the dollar still serves as the

world’s reserve currency, much as it did under Bretton Woods. Although floating rates do work as

automatic stabilizers, the effects may be unevenly distributed within countries. For example, the U.S.

fiscal expansion of the 1980s appreciated the dollar, limiting inflation overall. However, U.S. farmers were

hurt by this action as the stronger dollar weakened exports. With immobile factors of production, these

asymmetric effects can have long-run consequences. Finally, empirical evidence suggests that external

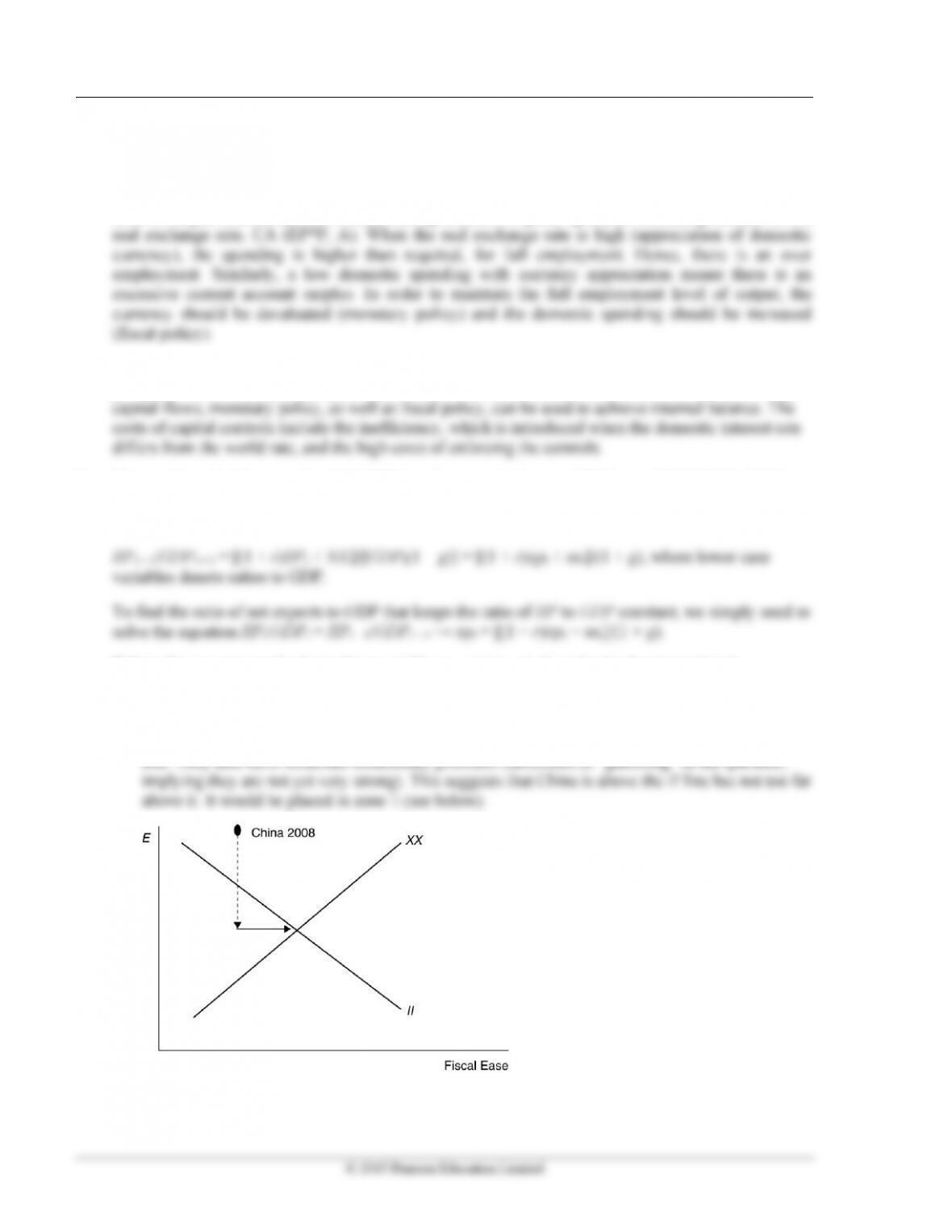

imbalances have actually increased since the adoption of floating exchange rates. The chapter concludes

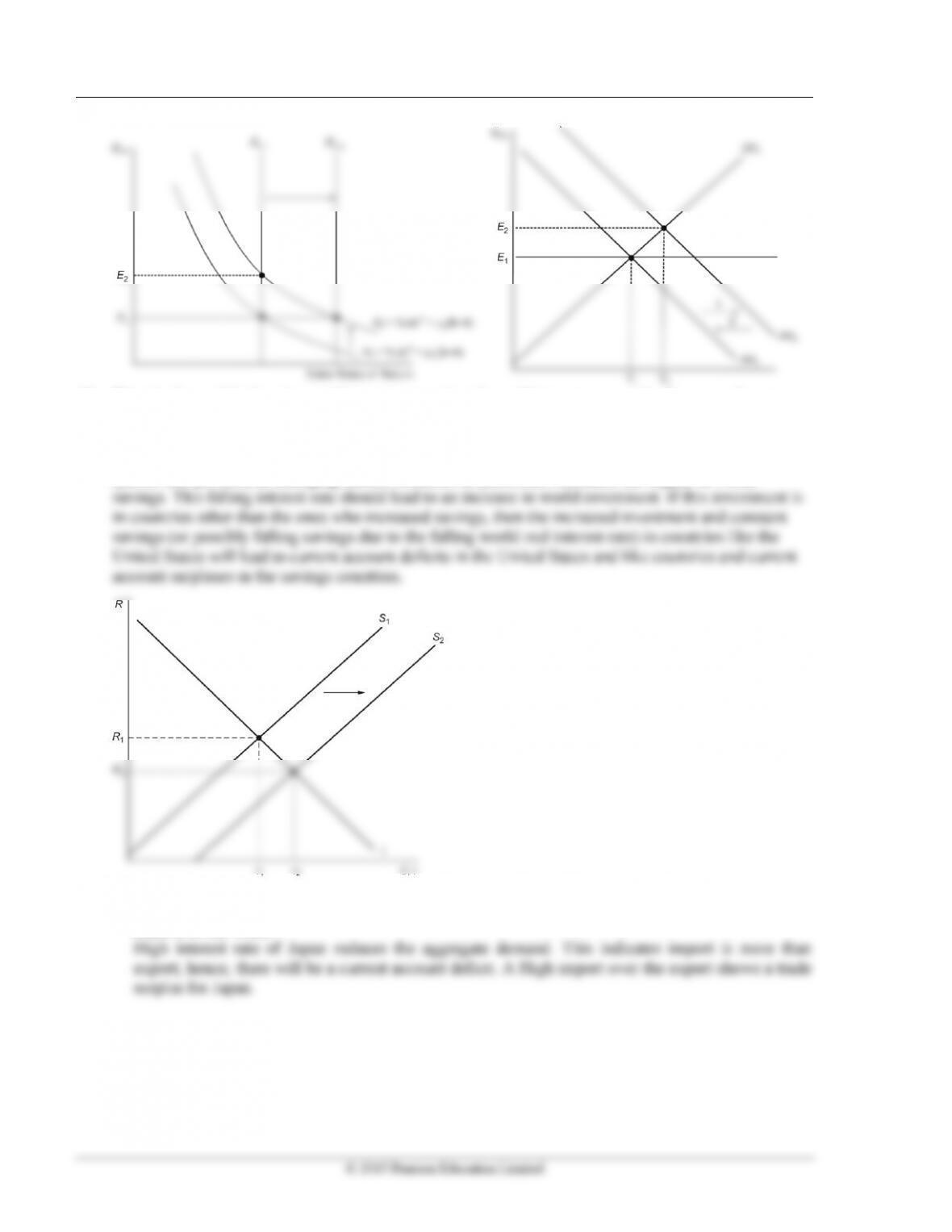

with a discussion of policy coordination under floating exchange rates. For example, a large country with a

current-account deficit that attempts to reduce its imbalance could cause global deflation. There is also a

market failure at work here in that policies by one country have external effects. For example, the 2007–

2009 financial crisis sparked a number of fiscal expansions in countries. Increased government spending in

the United States, for example, helped lift demand not just in the United States but in other countries as

well. Because the benefits of fiscal expansion are not fully internalized (though the costs are through

accumulated budget deficits), there will be an inefficiently small expansion from a global perspective.

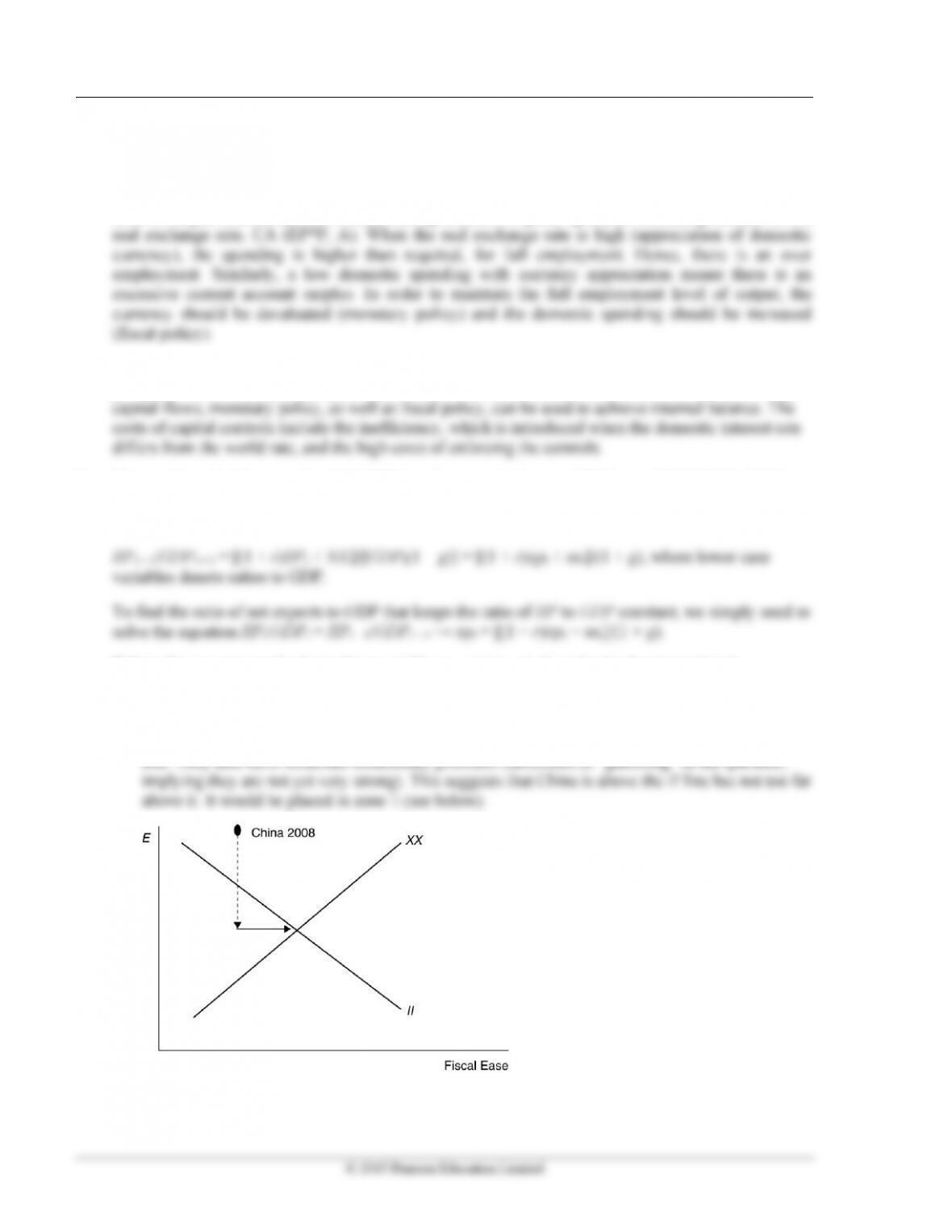

Thus, international policy coordination, even in a world of flexible exchange rates, may still be warranted.

This is especially relevant given the observation that given increased capital mobility, fixed exchange rates

may not even be an option for most countries in a world without international coordination of monetary

policy.