108 Krugman/Obstfeld/Melitz • International Economics: Theory & Policy, Tenth Edition

The Gold Standard

The Mechanics of a Gold Standard

Symmetric Monetary Adjustment under a Gold Standard

Benefits and Drawbacks of the Gold Standard

Bimetallic Standard

The Gold Exchange Standard

Case Study: The Demand for International Reserves

Summary

APPENDIX 1 TO CHAPTER 18 (7): Equilibrium in the Foreign-Exchange Market

with Imperfect Asset Substitutability

Demand

Supply

Equilibrium

APPENDIX 2 TO CHAPTER 18 (7): The Timing of Balance of Payments Crises

Online Appendix: The Monetary Approach to the Balance of Payments

◼ Chapter Overview

Open-economy macroeconomic analysis under fixed exchange rates is dual to the analysis of flexible

exchange rates. Under fixed exchange rates, attention is focused on the effects of policies on the balance of

payments (and the domestic money supply), taking the exchange rate as given. Conversely, under flexible

exchange rates with no official foreign-exchange intervention, the balance of payments equals zero, the

money supply is a policy variable, and analysis focuses on exchange rate determination. In the

intermediate case of managed floating, both the money supply and the exchange rate become, to an extent

that is determined by central bank policies, endogenous.

This chapter analyzes various types of monetary policy regimes under which the degree of exchange-

rate flexibility is limited. The reasons for devoting a chapter to this topic, more than 30 years after

the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system, include the prevalence of managed floating among

industrialized countries, the common use of fixed exchange rate regimes among developing countries,

the existence of regional currency arrangements such as the Exchange Rate Mechanism through which

some European nations peg to the euro, the recurrent calls for a new international monetary regime based

upon more aggressive exchange-rate management, and the irrevocably fixed rates among countries that use

the euro (a topic addressed in depth in Chapter 20 [9]).

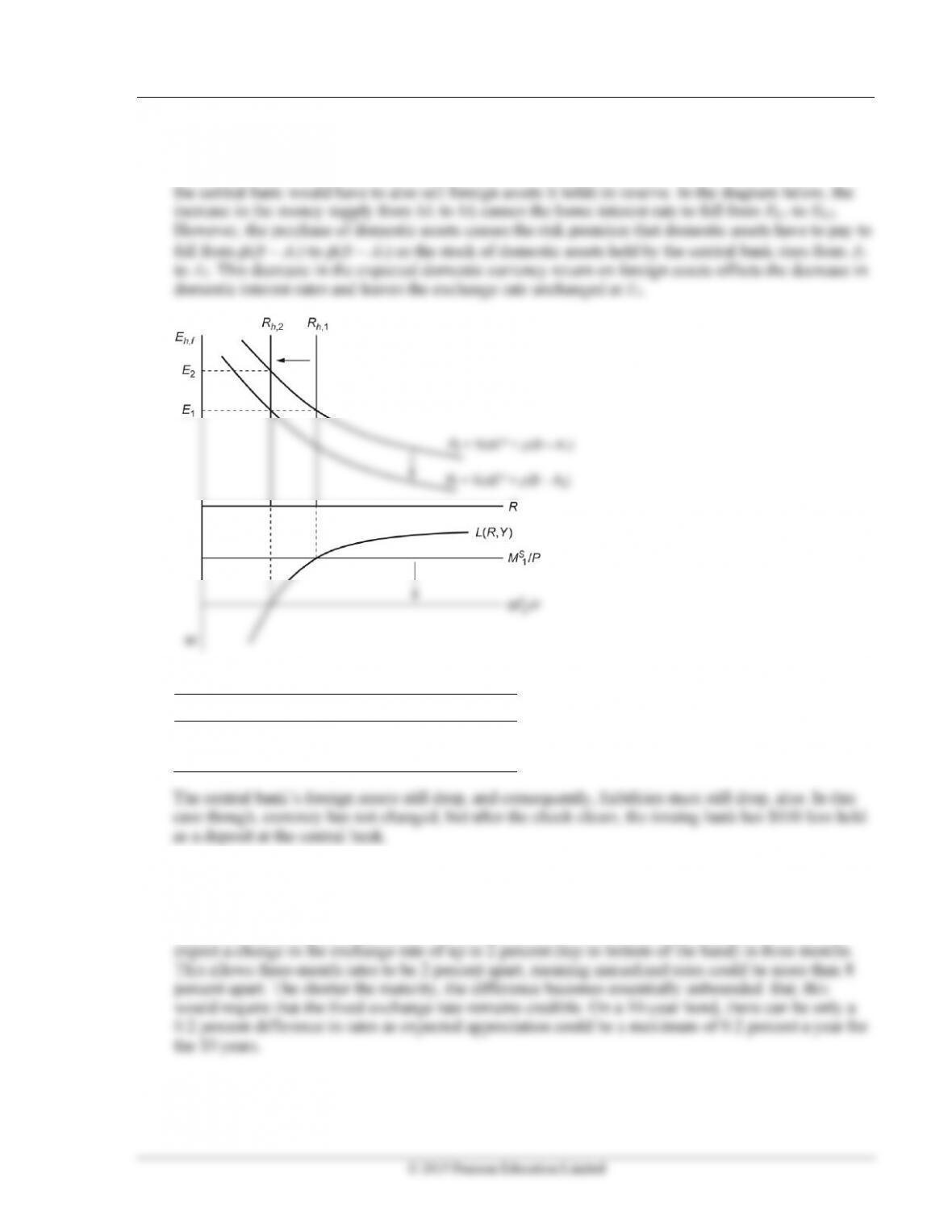

The chapter begins with an analysis of a stylized central bank balance sheet to show the link between

the balance of payments, official foreign-exchange intervention, and the domestic money supply. Also

described is sterilized intervention in foreign exchange, which changes the composition of interest-bearing

assets held by the public but not the money supply. This analysis is then combined with the exchange rate

determination analysis of Chapter 15(4) to demonstrate the manner in which central banks alter the money

supply to peg the nominal exchange rate. The endogeneity of the money supply under fixed exchange rates

emerges as a key lesson of this discussion.

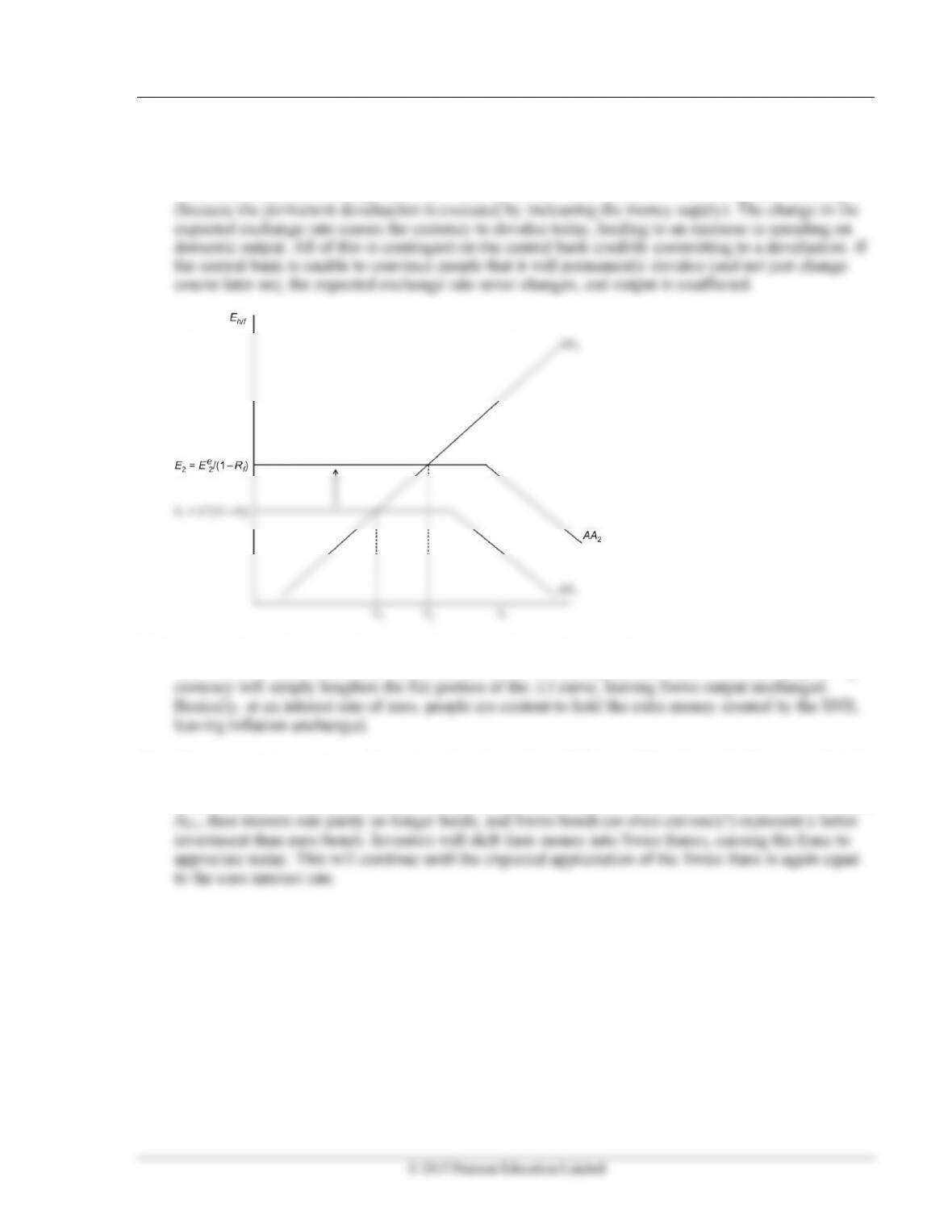

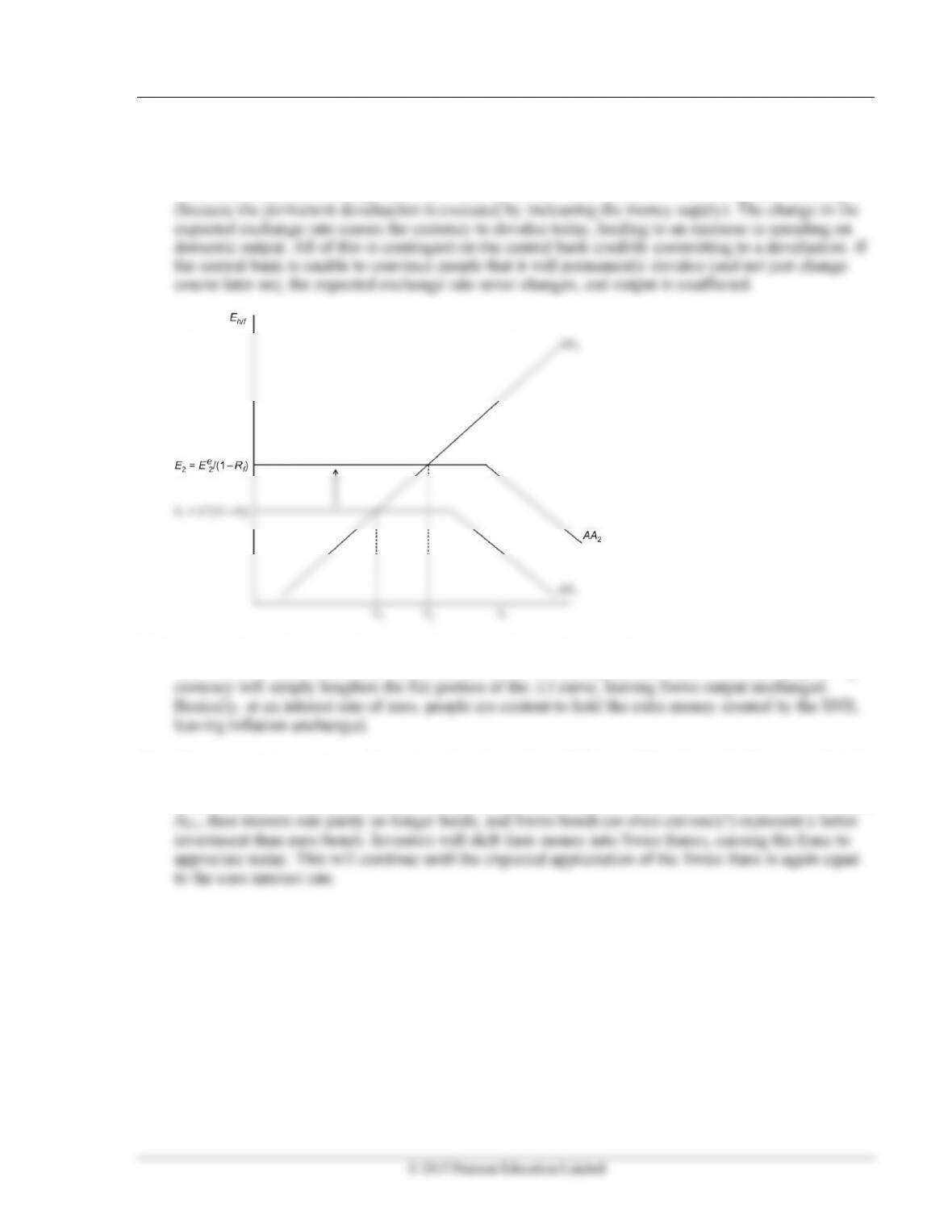

The tools developed in Chapter 17(6) are employed to demonstrate the impotence of monetary policy and

the effectiveness of fiscal policy under a fixed exchange rate regime. The short-run and long-run effects of

devaluation and revaluation are examined. The setup already developed suggests a natural description of

balance of payments crises as episodes in which the public comes to expect a future currency devaluation.