98 Krugman/Obstfeld/Melitz • International Economics: Theory & Policy, Tenth Edition

Macroeconomic Policies and the Current Account

Gradual Trade Flow Adjustment and Current Account Dynamics

The J-Curve

Exchange Rate Pass-Through and Inflation

The Current Account, Wealth, and Exchange Rate Dynamics

The Liquidity Trap

Case Study: How Big Is the Government Spending Multiplier?

Summary

APPENDIX 1 TO CHAPTER 17 (6): Intertemporal Trade and Consumption Demand

APPENDIX 2 TO CHAPTER 17 (6): The Marshall-Lerner Condition and

Empirical Estimates of Trade Elasticities

Online Appendix: The IS-LM and the DD-AA Model

◼ Chapter Overview

This chapter integrates the previous analysis of exchange rate determination with a model of short-run

output determination in an open economy. The model presented is similar in spirit to the classic Mundell-

Fleming model, but the discussion goes beyond the standard presentation in its contrast of the effects of

temporary versus permanent policies. The distinction between temporary and permanent policies allows

for an analysis of dynamic paths of adjustment rather than just comparative statics. This dynamic analysis

brings in the possibility of a J-curve response of the current account to currency depreciation. The chapter

concludes with a discussion of exchange rate pass-through, that is, the response of import prices to

exchange rate movements.

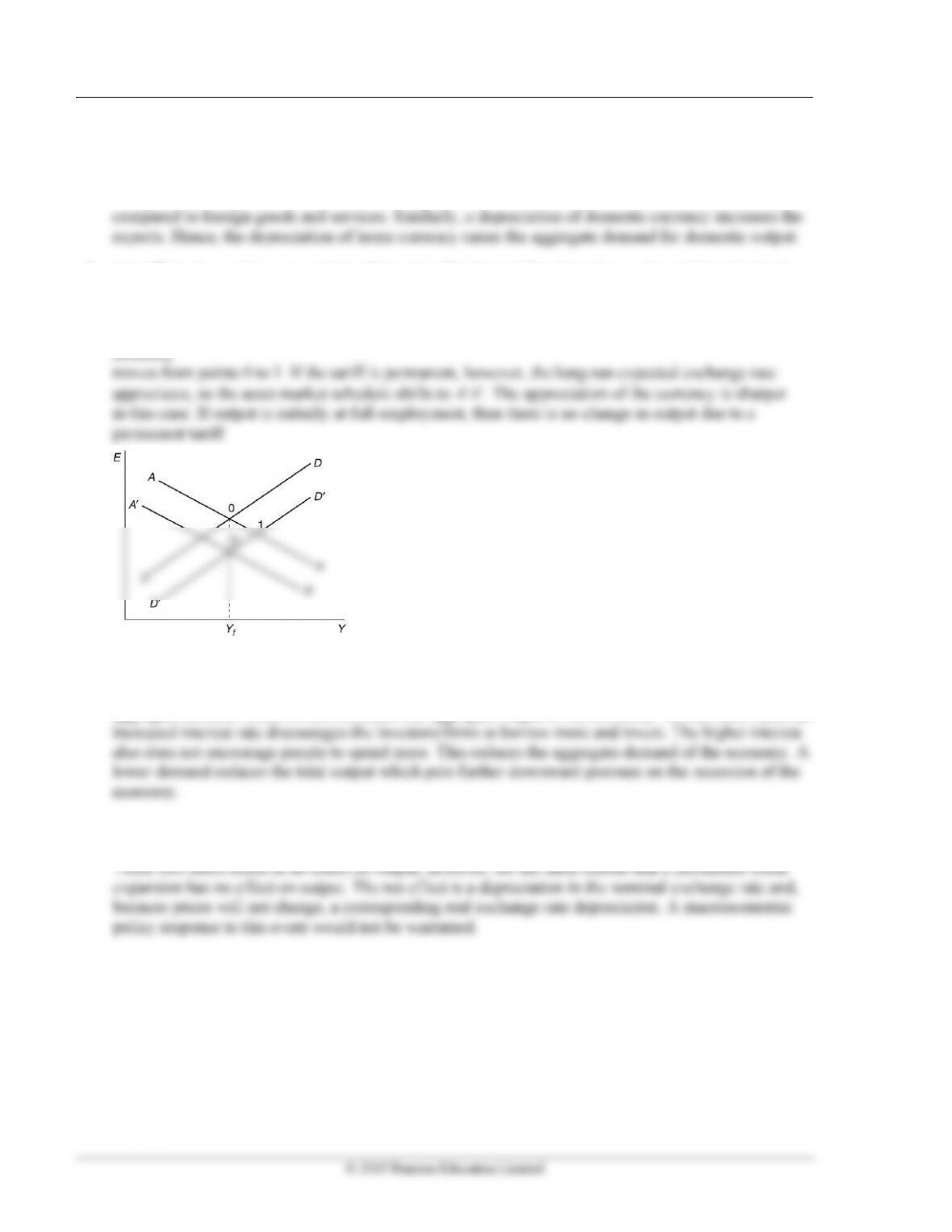

The chapter begins with the development of an open-economy fixed-price model. An aggregate demand

function is derived using a Keynesian cross diagram in which the real exchange rate serves as a shift

parameter. A nominal currency depreciation increases output by stimulating exports and reducing imports,

given foreign and domestic prices, fiscal policy, and investment levels. This yields a positively sloped

output-market equilibrium (DD) schedule in exchange rate output space. A negatively sloped asset-market

equilibrium (AA) schedule completes the model. The derivation of this schedule follows from the analysis

of previous chapters. For students who have already taken intermediate macroeconomics, you may want to

point out that the intuition behind the slope of the AA curve is identical to that of the LM curve, with the

additional relationship of interest parity providing the link between the closed-economy LM curve and the

open-economy AA curve. As with the LM curve, higher income increases money demand and raises the

home-currency interest rate (given real balances). In an open economy, higher interest rates require currency

appreciation to satisfy interest parity (for a given future expected exchange rate).

The effects of temporary policies, as well as the short-run and long-run effects of permanent policies, can

be studied in the context of the DD-AA model if we identify the expected future exchange rate with the

long-run exchange rate examined in Chapters 15 (4) and 16 (5). In line with this interpretation, temporary

policies are defined to be those that leave the expected exchange rate unchanged, while permanent policies

are those that move the expected exchange rate to its new long-run level. As in the analysis in earlier

chapters, in the long run, prices change to clear markets (if necessary). Although the assumptions concerning

the expectational effects of temporary and permanent policies are unrealistic as an exact description of an

economy, they are pedagogically useful because they allow students to grasp how differing market

expectations about the duration of policies can alter their qualitative effects. Students may find the