11

This model concludes by predicting:

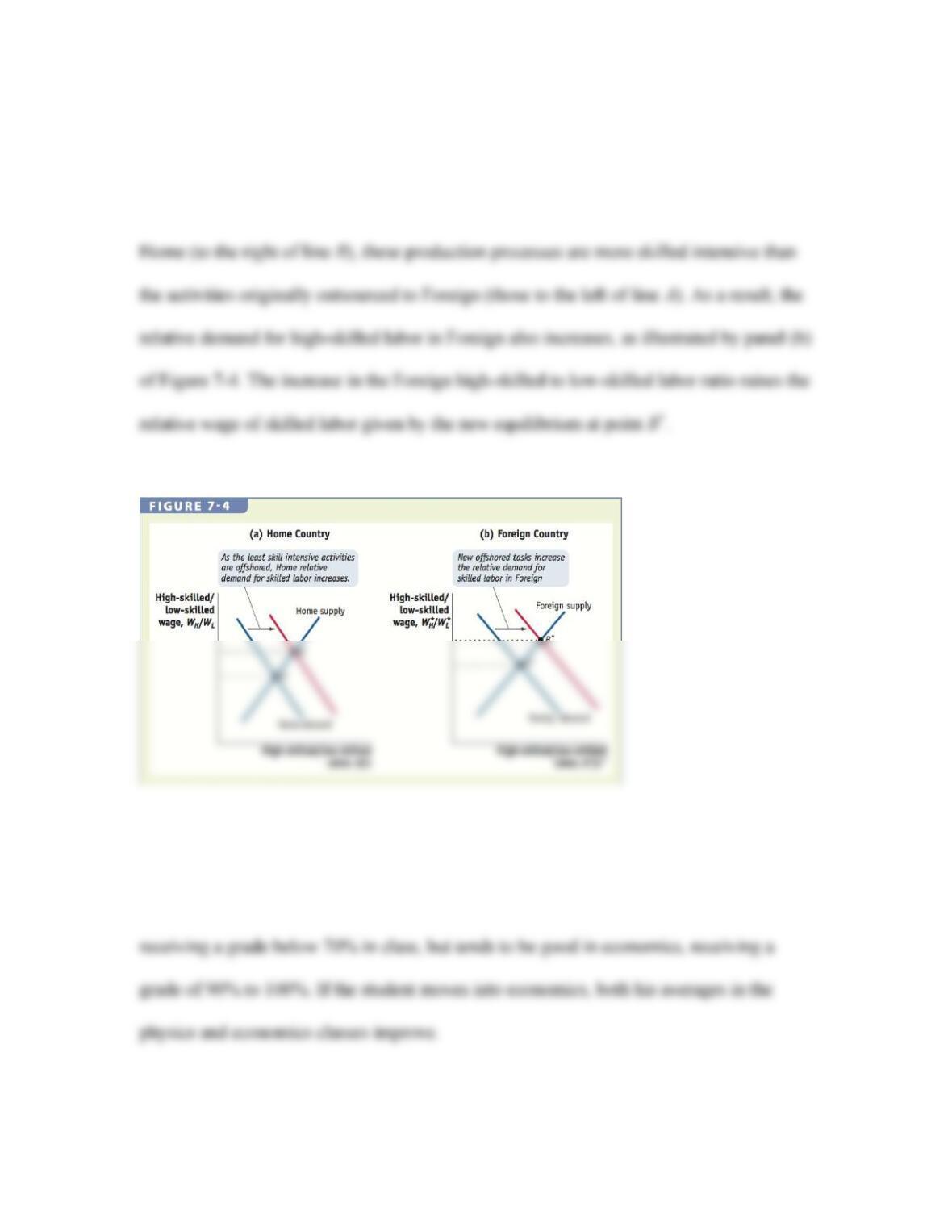

As activities in the middle of the value chain are shifted by offshoring from Home to

Foreign, they raise the relative demand for skilled labor in both countries because these

2 Explaining Changes in Wages and Employment

The wage differential between high-skilled and low-skilled workers in developed

countries such as the United States, Australia, Canada, Japan, Sweden, and the United

Kingdom, as well as less-developed countries such as Chile, Hong Kong, and Mexico,

has increased since the early 1980s. So, at first glance the data appear to be consistent

with our model. But, let’s take a closer look at the data for Mexico and the United States.

What has the change in wages and employment been due to offshoring for these two

countries?

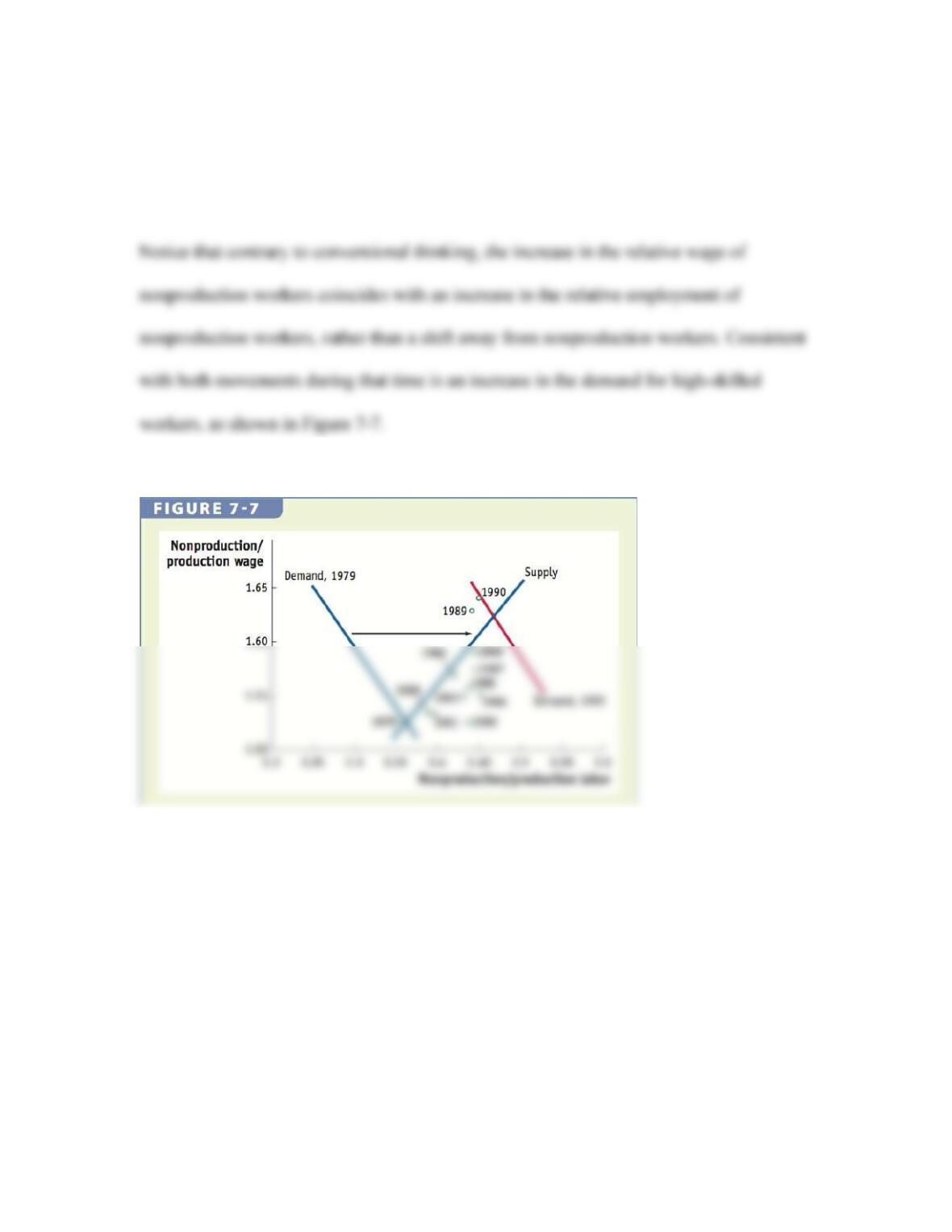

Changes in the Relative Wage of Non-Productive Workers in the United States A

comparison of the wage movements in the manufacturing industries allows us to more

accurately attribute each factor explaining the widening wage differential experienced in

the United States.

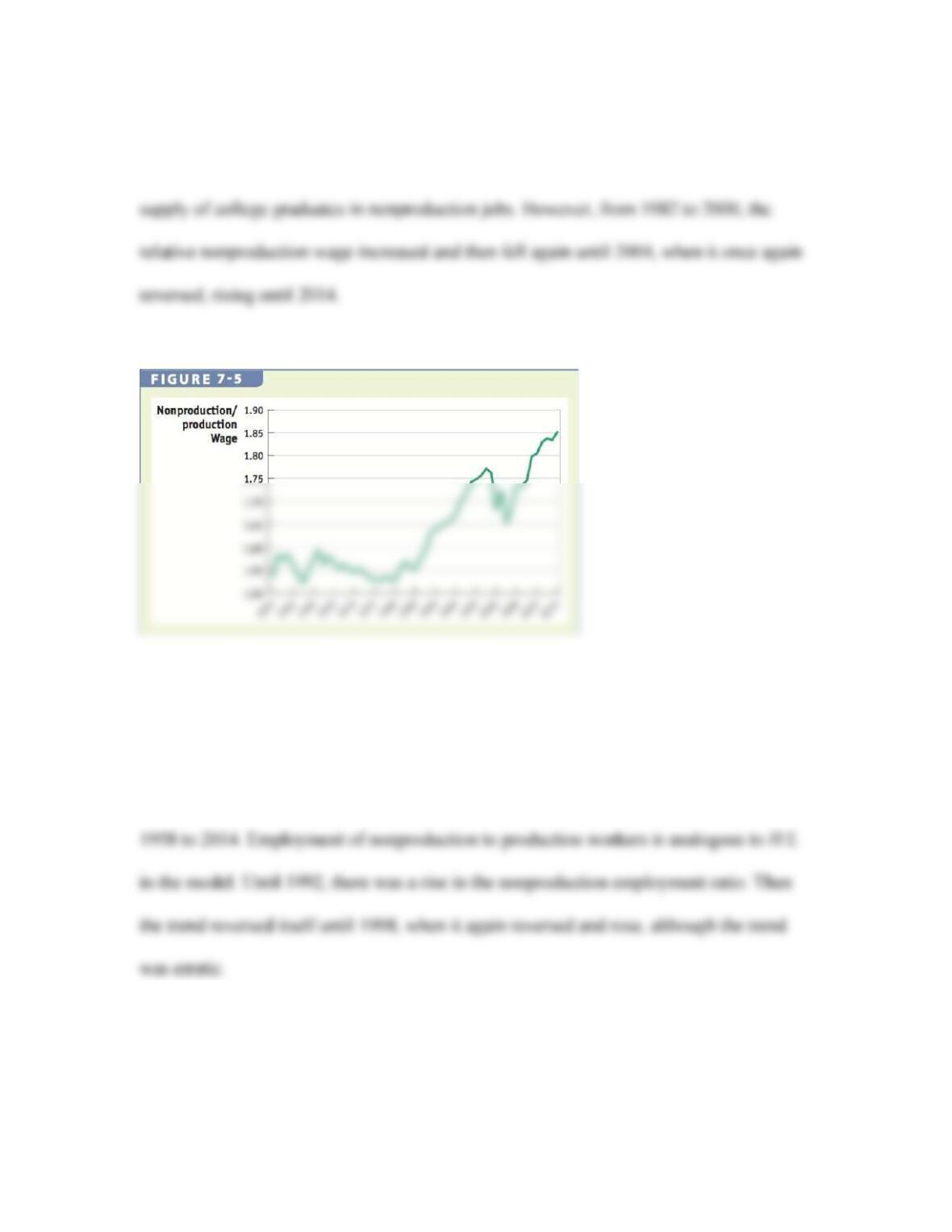

From Figure 7-5, we see that the average annual earnings of nonproduction workers

relative to production workers in U.S. manufacturing did not follow any particular trend