ADVANCED TOPIC

7-8 Implicit Contracts

In the mid-1970s, a number of authors provided another explanation of wage rigidity: Firms and workers

might find it in their mutual best interest to write wage contracts that specified a fixed wage.1 The basic

intuition is that in an uncertain world, contracts may serve more than one function. As well as being the

means whereby workers are remunerated for their services, they may also be a means for the firm to insure

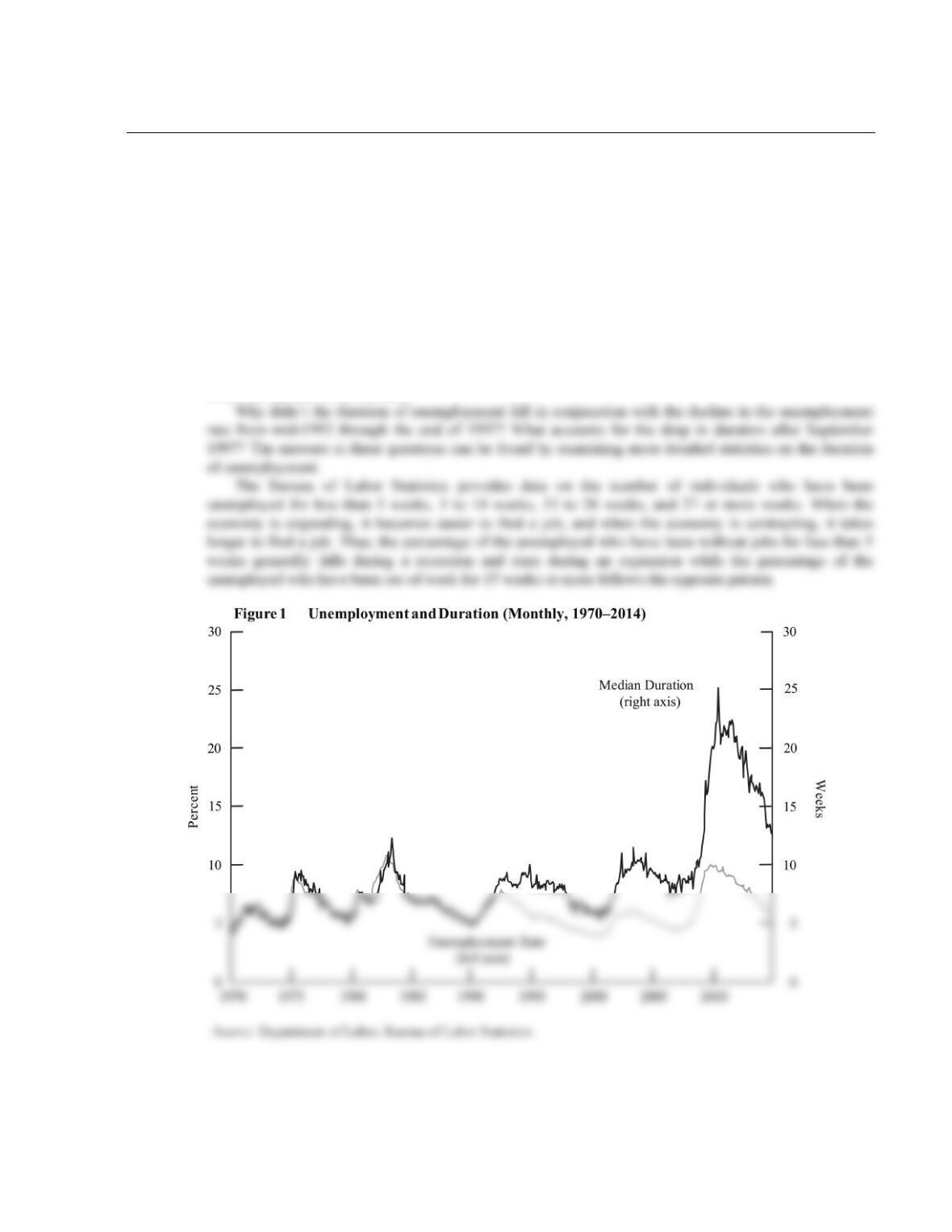

research first appeared, many economists thought that it would provide a good microeconomic theory of

unemployment that was immune from the Lucas $500 bill criticism.2

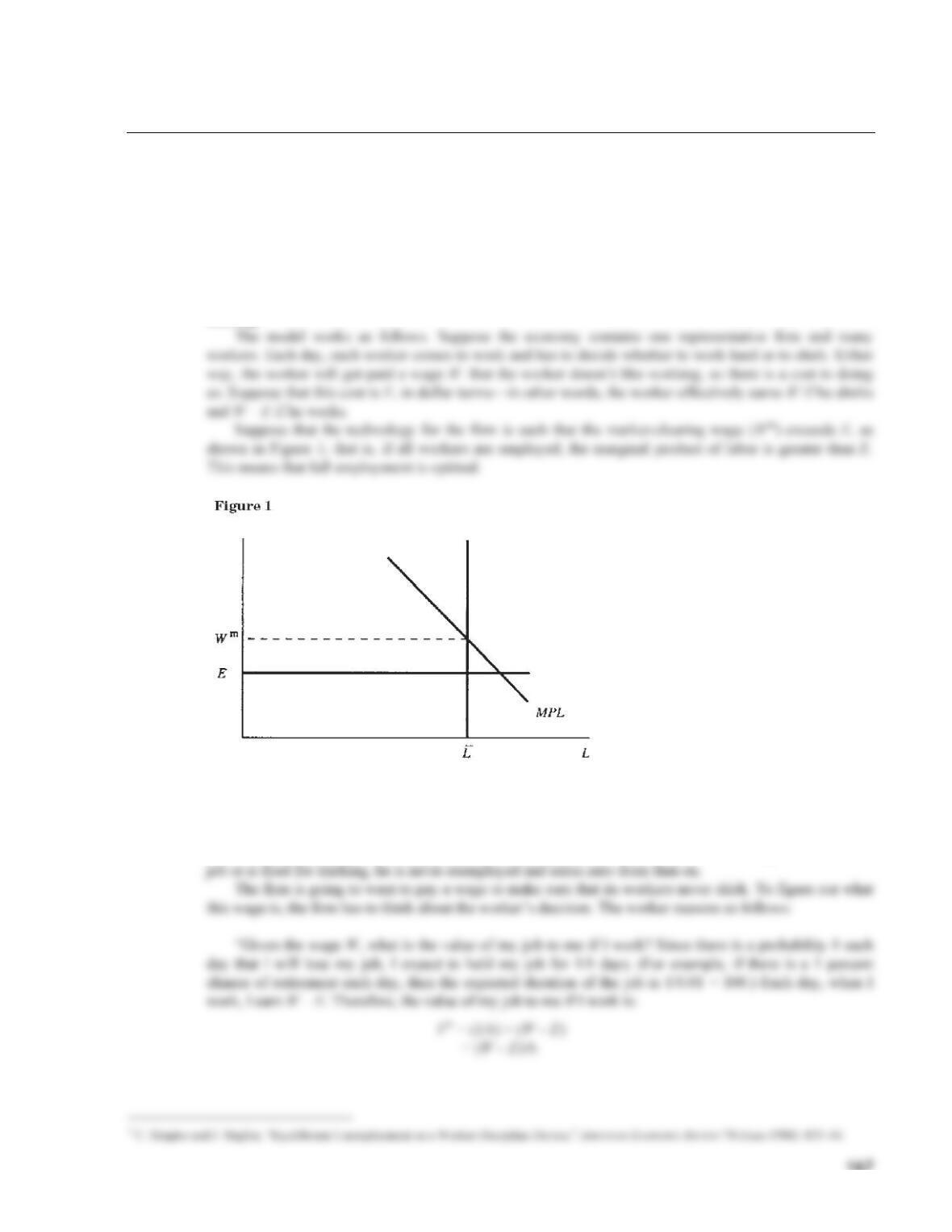

Let us consider the environment in which such contracts make sense. The first idea is that the world is

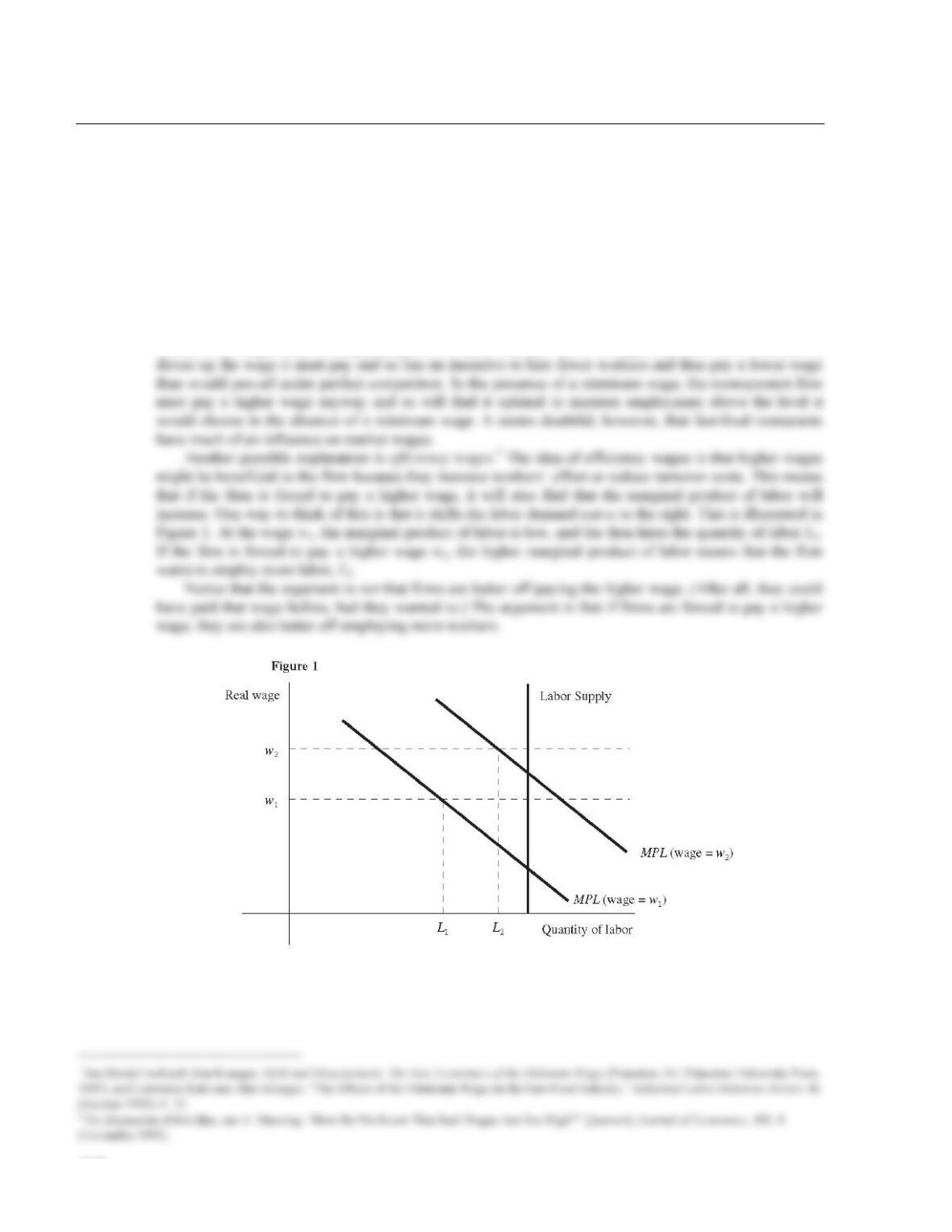

uncertain so that, in the absence of contracts, workers’ wages fluctuate: In good “states of the world,”

workers’ productivity, and hence their wage, is high; in bad states of the world, their wage is low.3

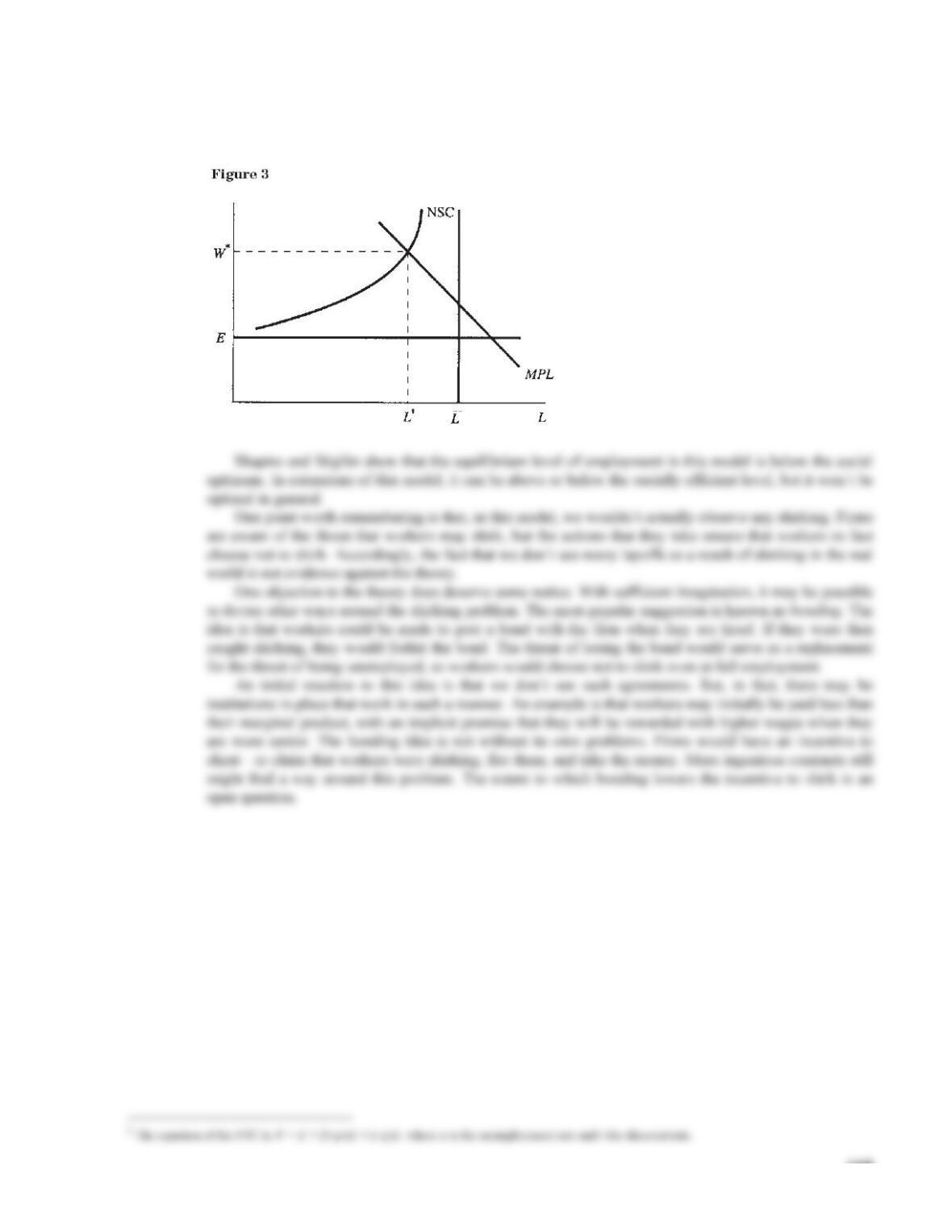

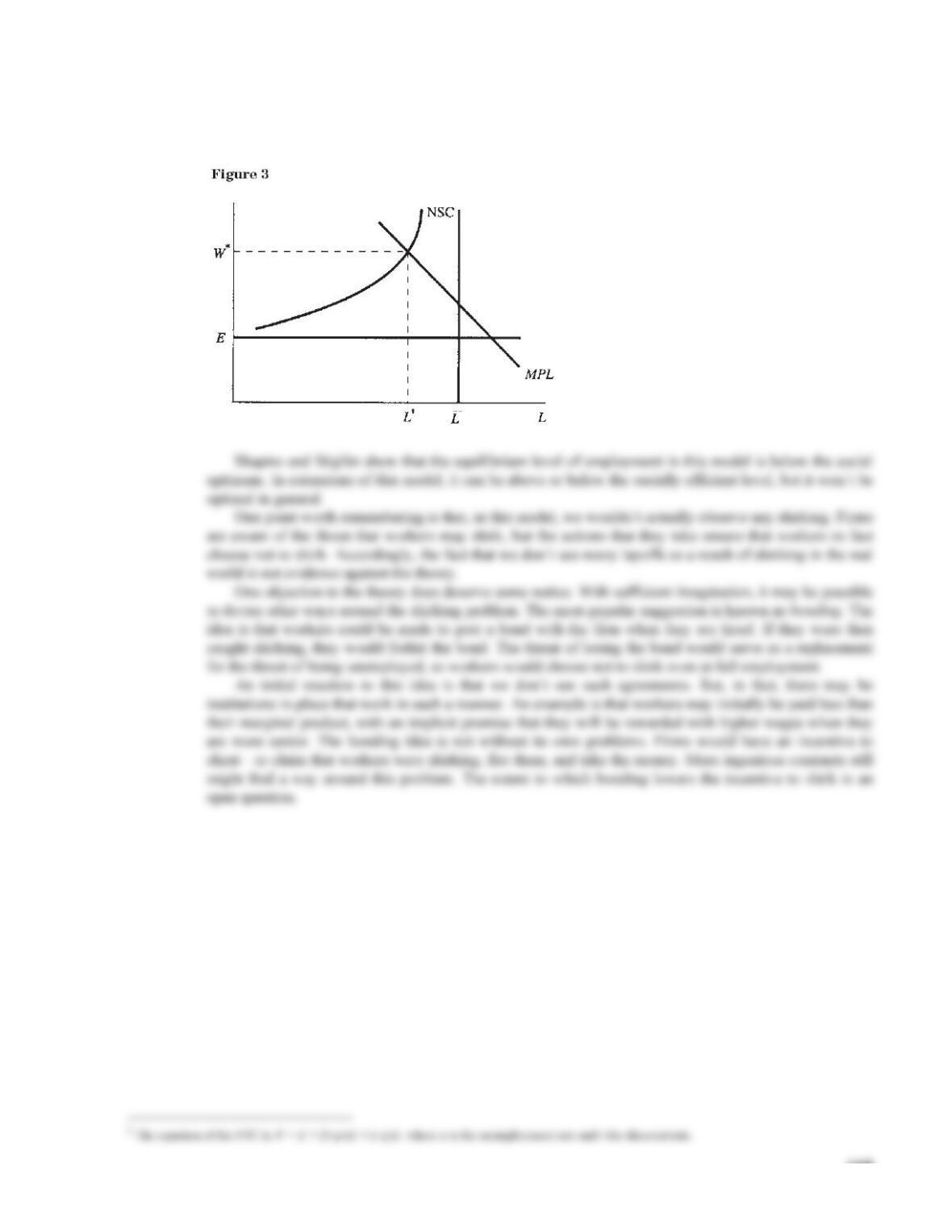

this implies unemployment—in an optimal contract, the wage and employment decisions are separated. It

turns out that, overall, contract theory does not really explain unemployment very easily: Optimal

contracts often imply higher employment than would occur in an auction market.

Early models also included some important unexplained restrictions on the form of contracts, such as

no work-sharing or severance pay. When these assumptions were relaxed, the models no longer generated

1 The seminal papers are C. Azariadis, “Implicit Contracts and Underemployment Equilibria,” Journal of Political Economy 83 (1975): 1183–1202;

and M.N. Baily, “Wages and Employment Under Uncertain Demand,” Review of Economic Studies 83, no. 41 (1974): 37–50. There are also many

good surveys of this literature; see, for example, R. Cooper, Wage and Employment Patterns in Labor Contracts: Microfoundations and

Macroeconomic Implications (Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1987); C. Davidson, Recent Developments in the Theory of

Involuntary Unemployment (Kalamazoo, MI: Upjohn, 1990); and J. Stiglitz, “Theories of Wage Rigidity,” in J. Butkiewicz et al., eds., Keynes’