Deriving the Gravity Equation To derive the gravity equation, we assume each country

produces a differentiated product to apply the monopolistic competition model. With a

differentiated product, the import demand for goods produced by Country 1 depends on

(1) the relative size of the importing country and (2) the distance between the two

countries. The relative size of the importing country (Country 2) is measured by its GDP,

as compared with the rest of the world (Share2 = GDP2/GDPW). The distance between the

two countries provides a measure for the transportation costs associated with exporting

the good from one country to another. Raising to the distance between Country 1 and

Country 2 power, or distn, we have that the exports from the former to the latter are equal

to the following equation:

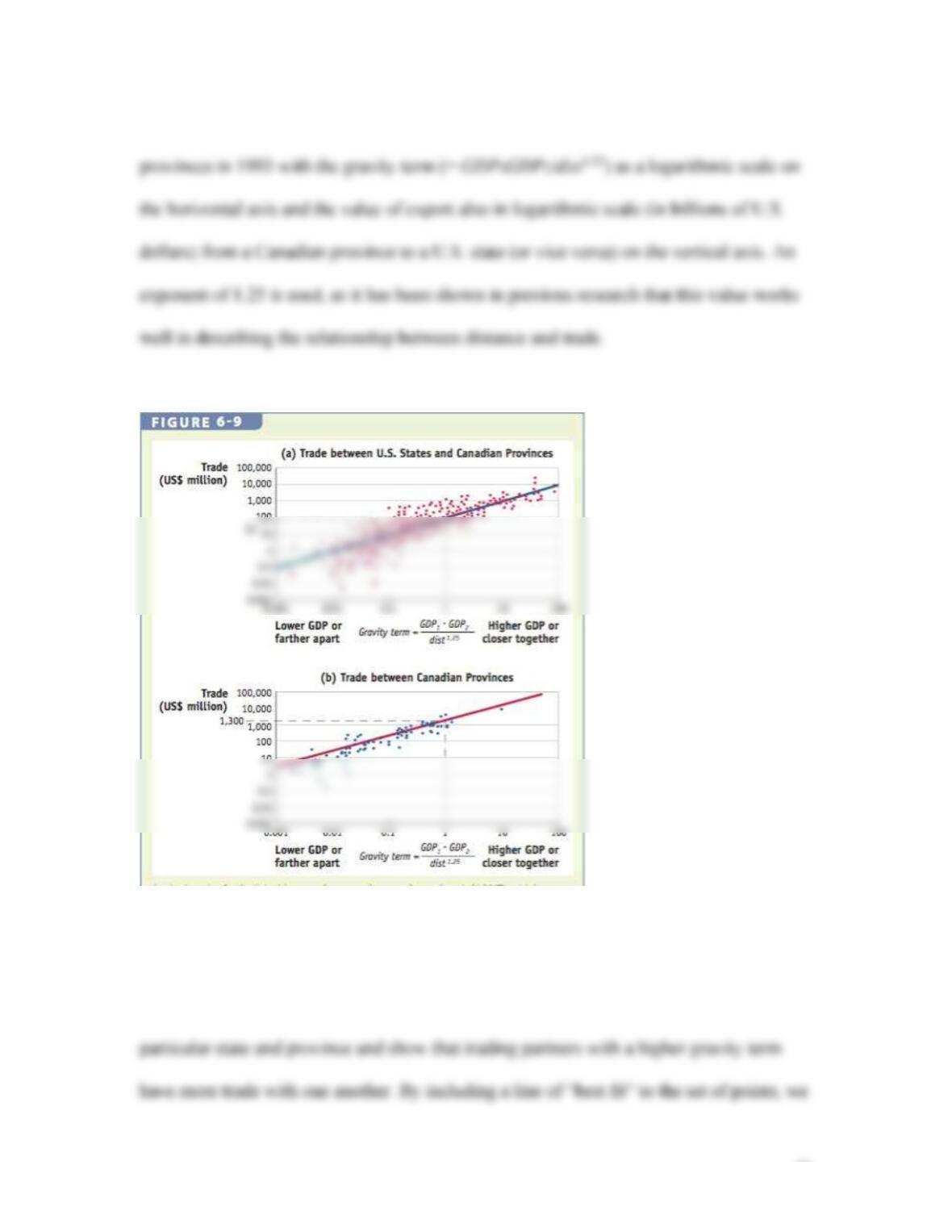

APPLICATION

The Gravity Equation for Canada and the United States

The gravity equation may be applied between countries, provinces, or even states of a