346 ❖ Chapter 21/The Theory of Consumer Choice

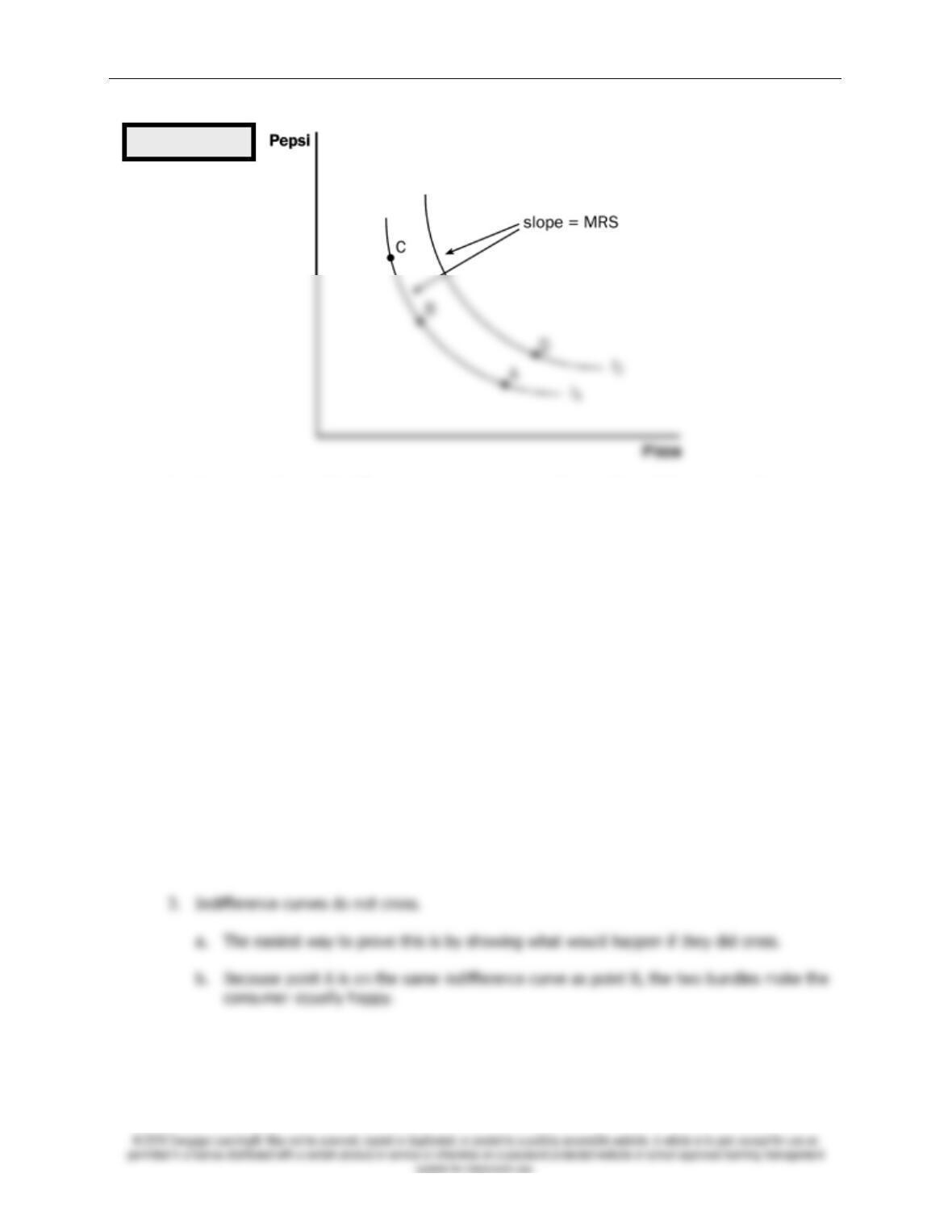

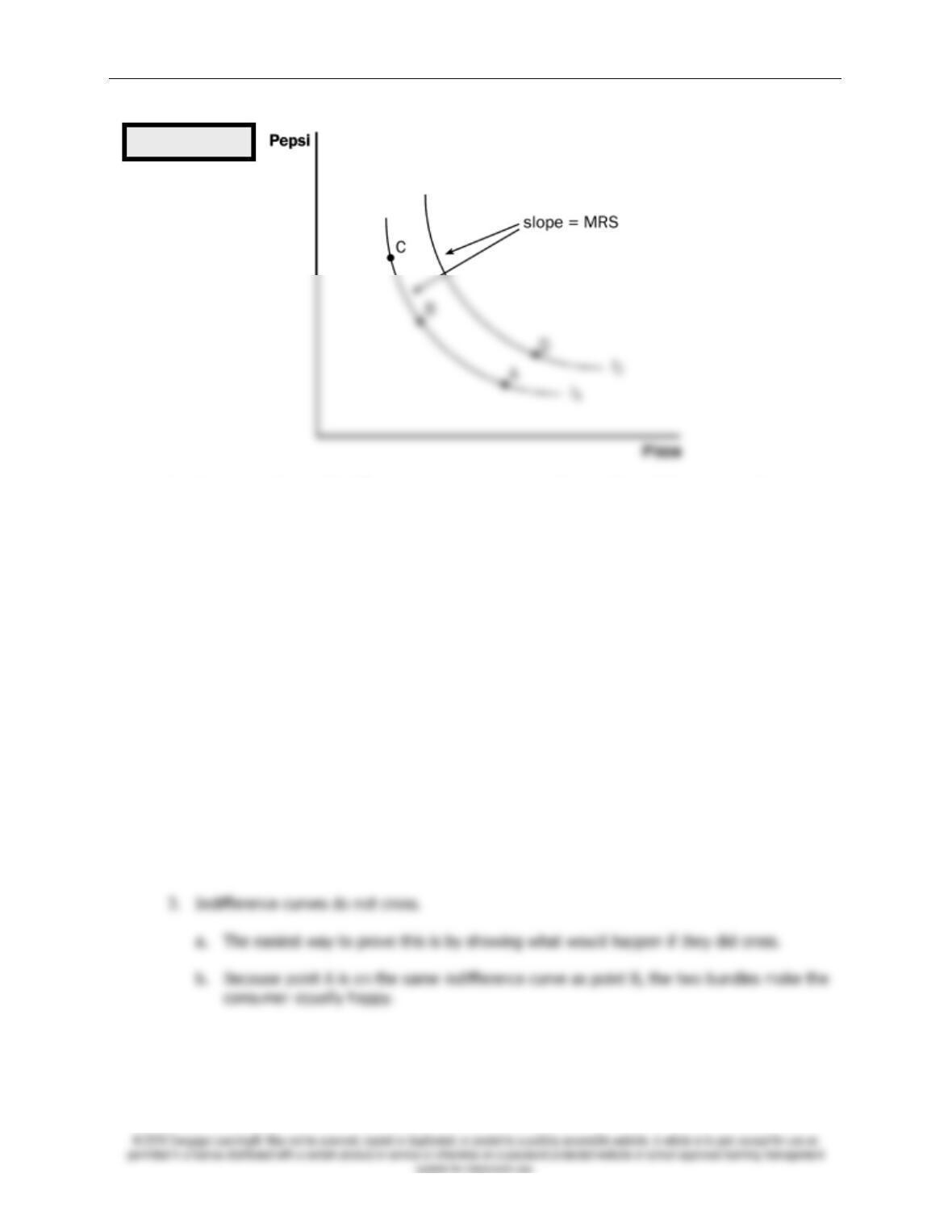

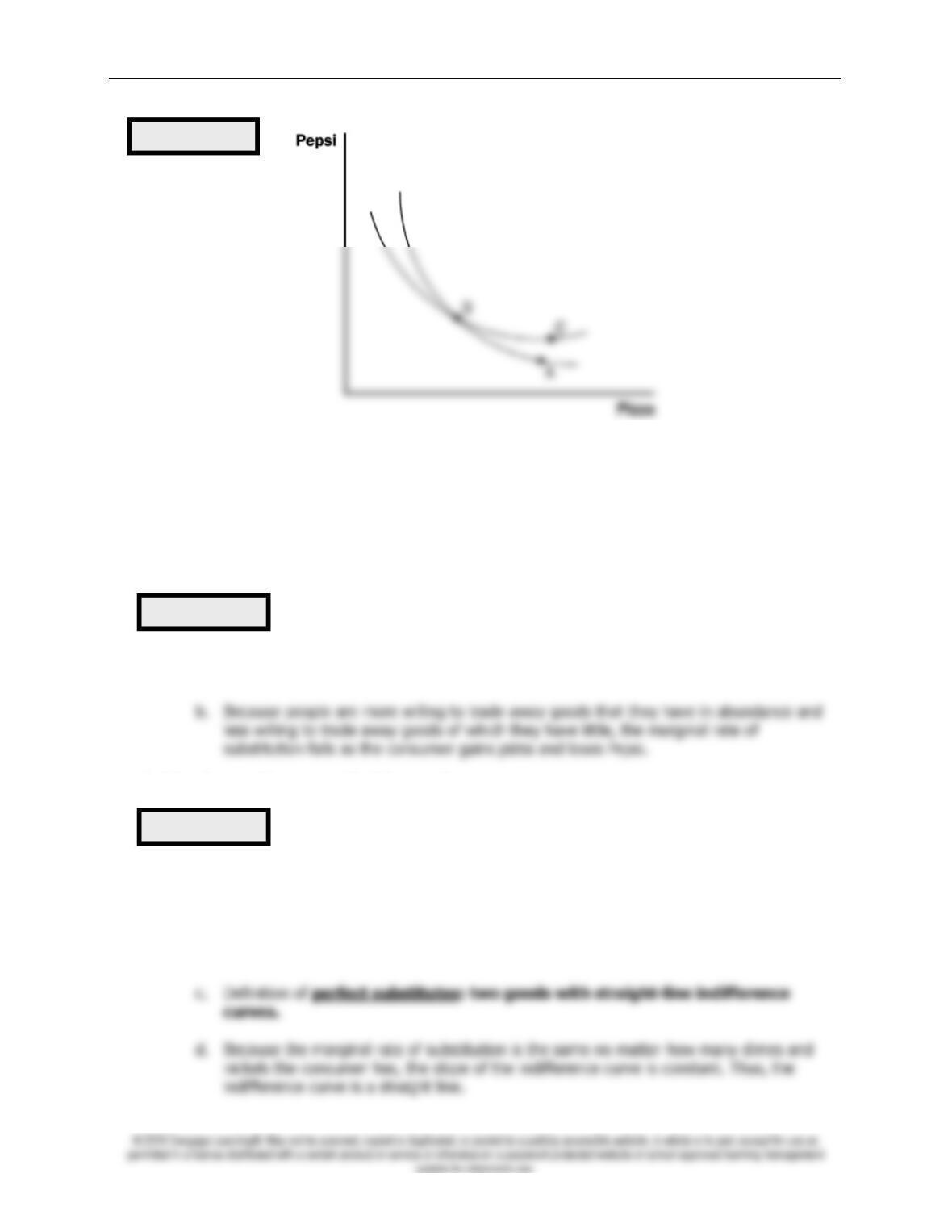

are preferred to points on lower indifference curves. The slope of an indifference curve at any point is

the consumer's marginal rate of substitution—the rate at which the consumer is willing to trade one

good for the other.

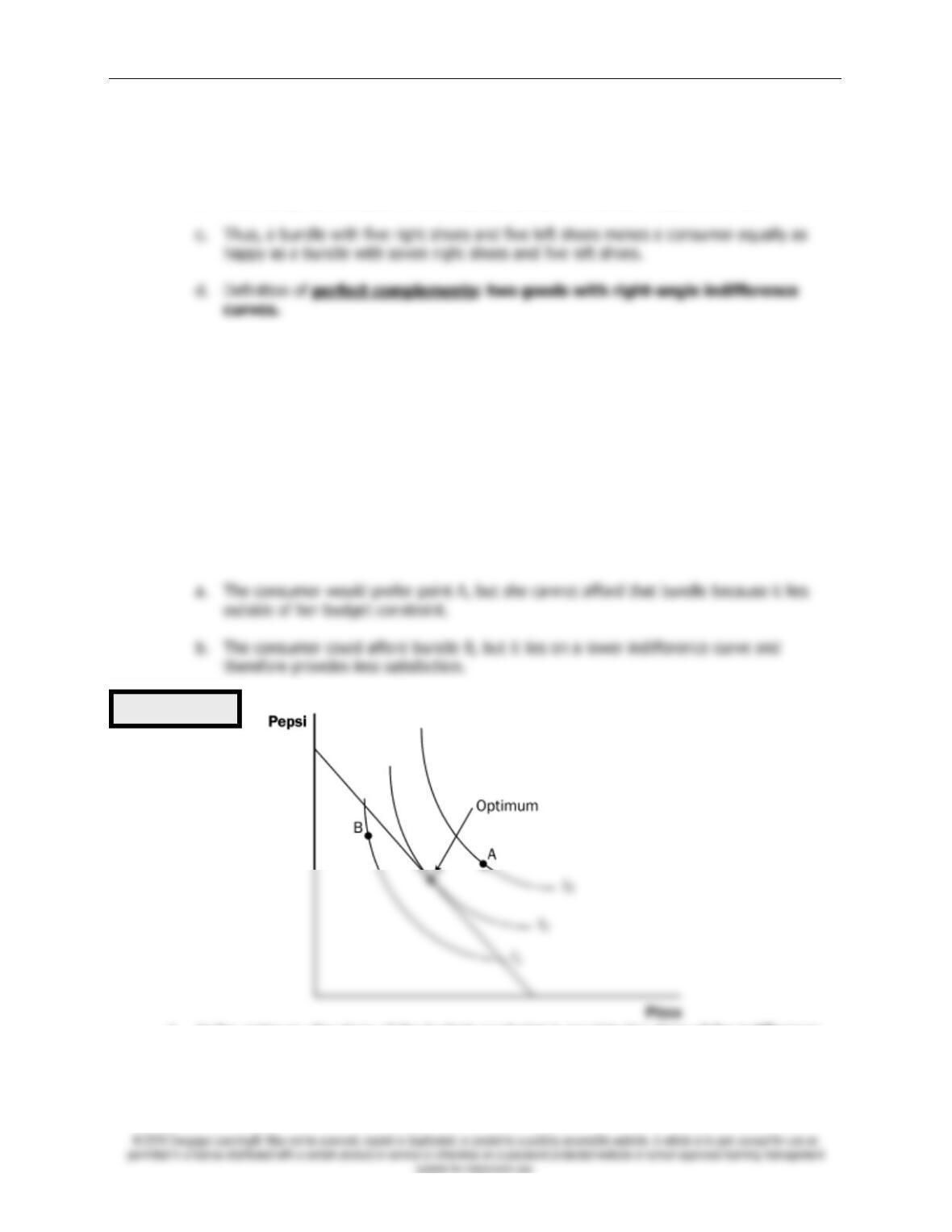

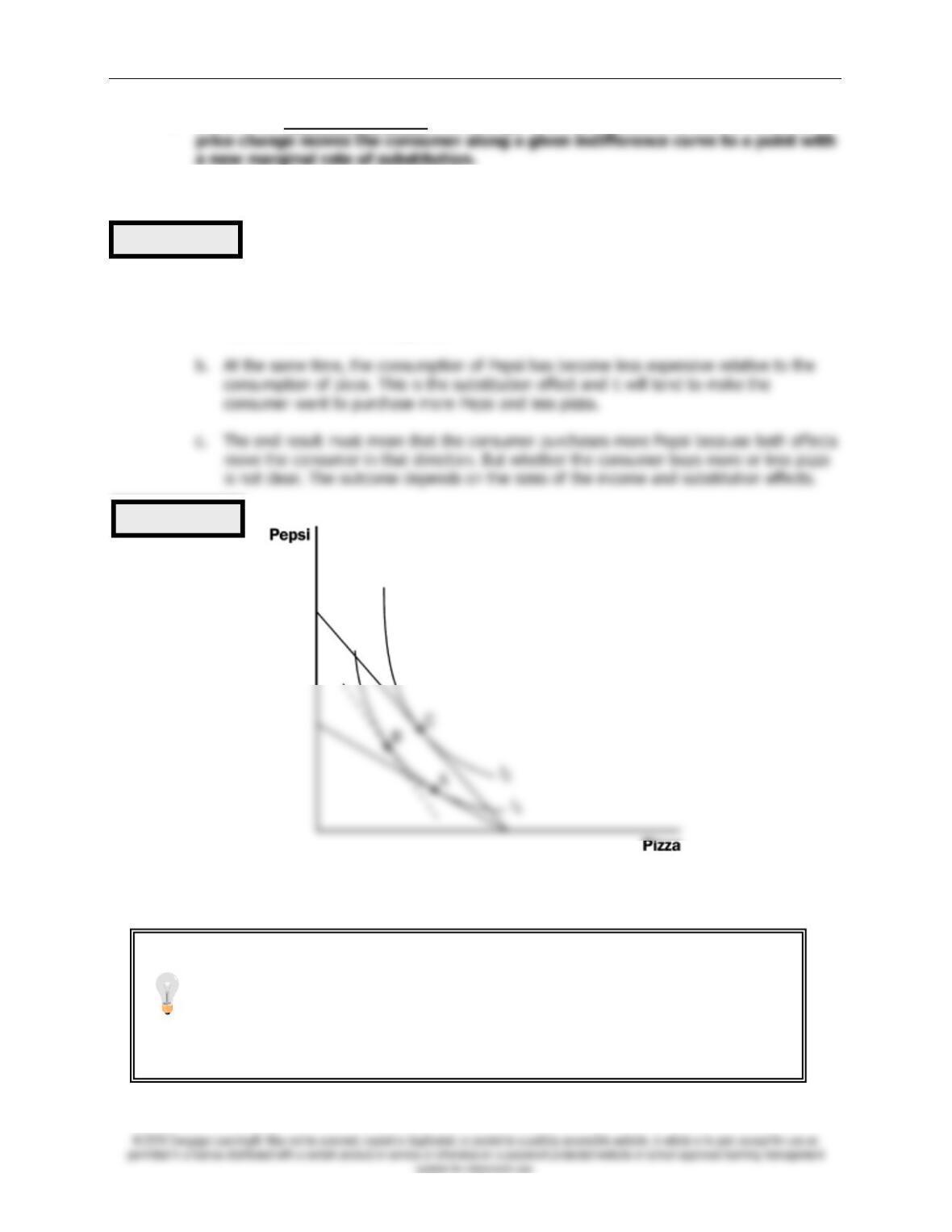

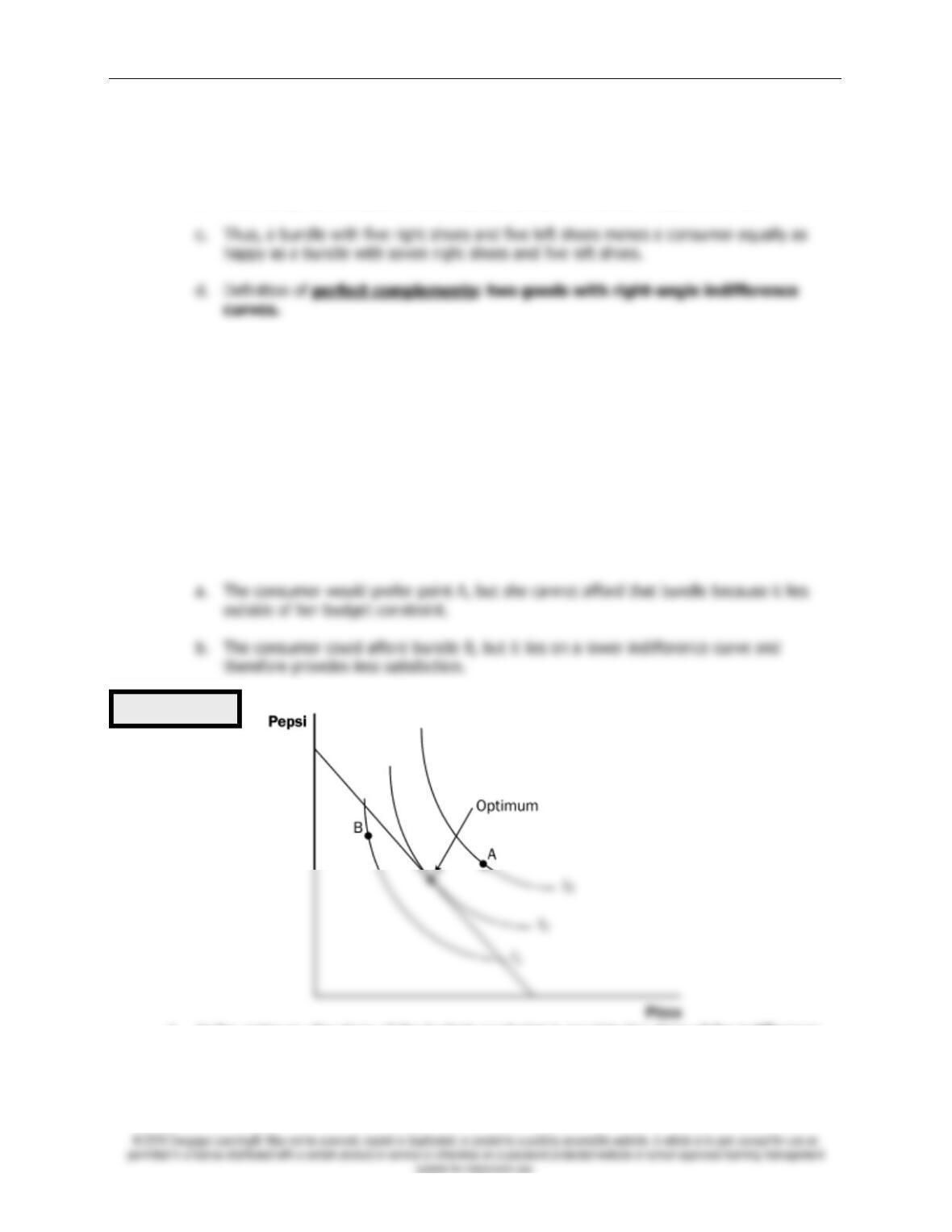

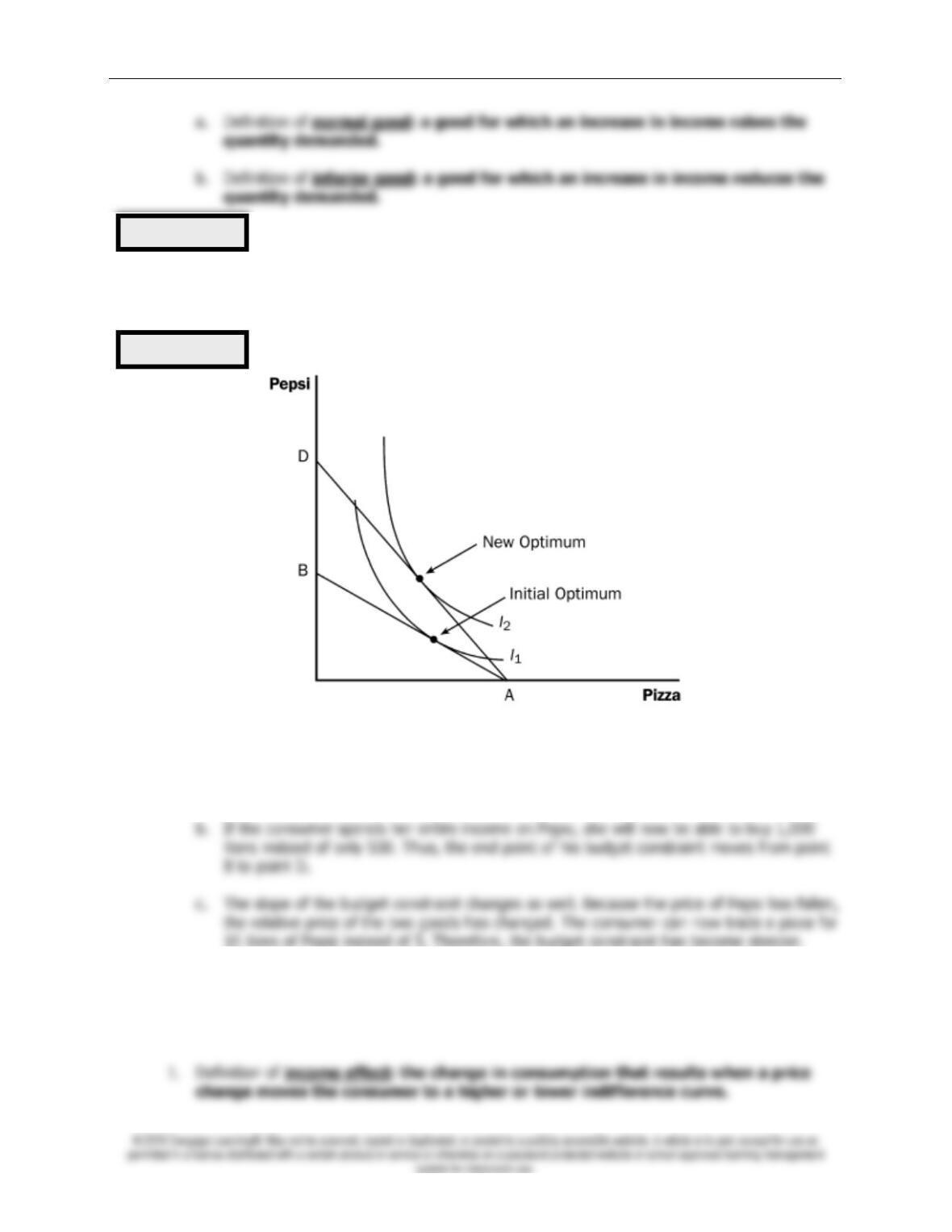

• When the price of a good falls, the impact on the consumer’s choices can be broken down into an

income effect and a substitution effect. The income effect is the change in consumption that arises

because a lower price makes the consumer better off. The substitution effect is the change in

consumption that arises because a price change encourages greater consumption of the good that

has become relatively cheaper. The income effect is reflected in the movement from a lower to a

higher indifference curve, whereas the substitution effect is reflected by a movement along an

indifference curve to a point with a different slope.

• The theory of consumer choice can be applied in many situations. It explains why demand curves can

potentially slope upward, why higher wages could either increase or decrease the quantity of labor

supplied, and why higher interest rates could either increase or decrease saving.

CHAPTER OUTLINE:

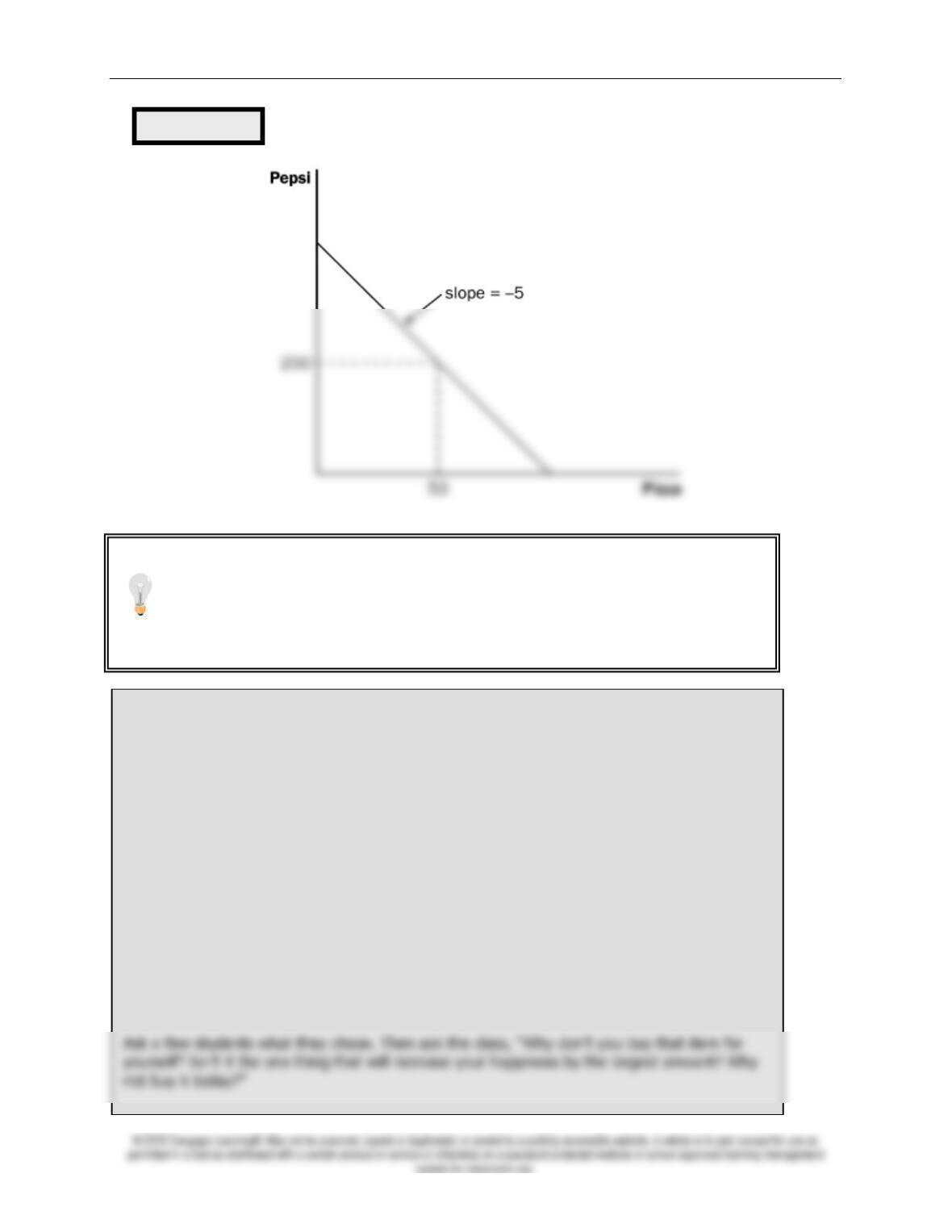

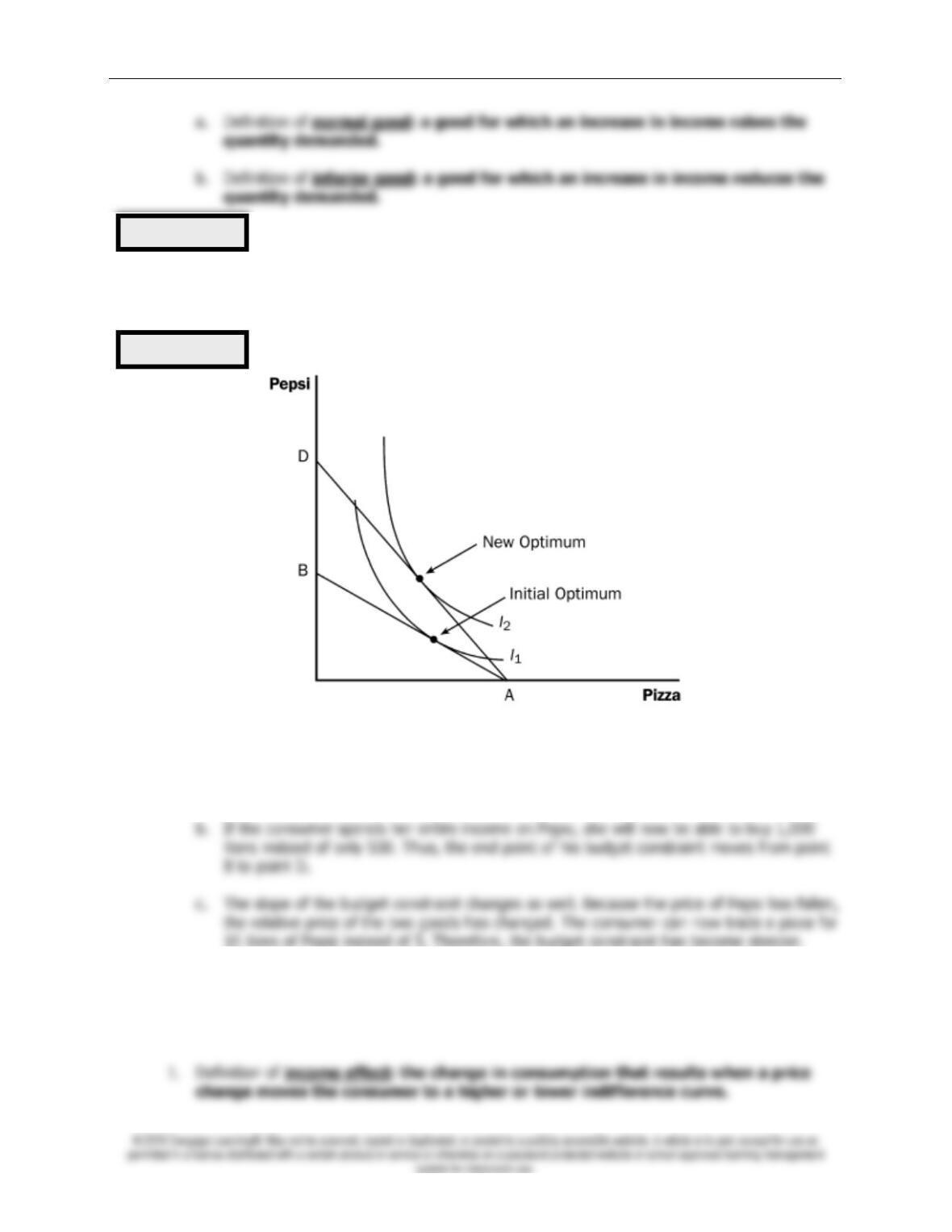

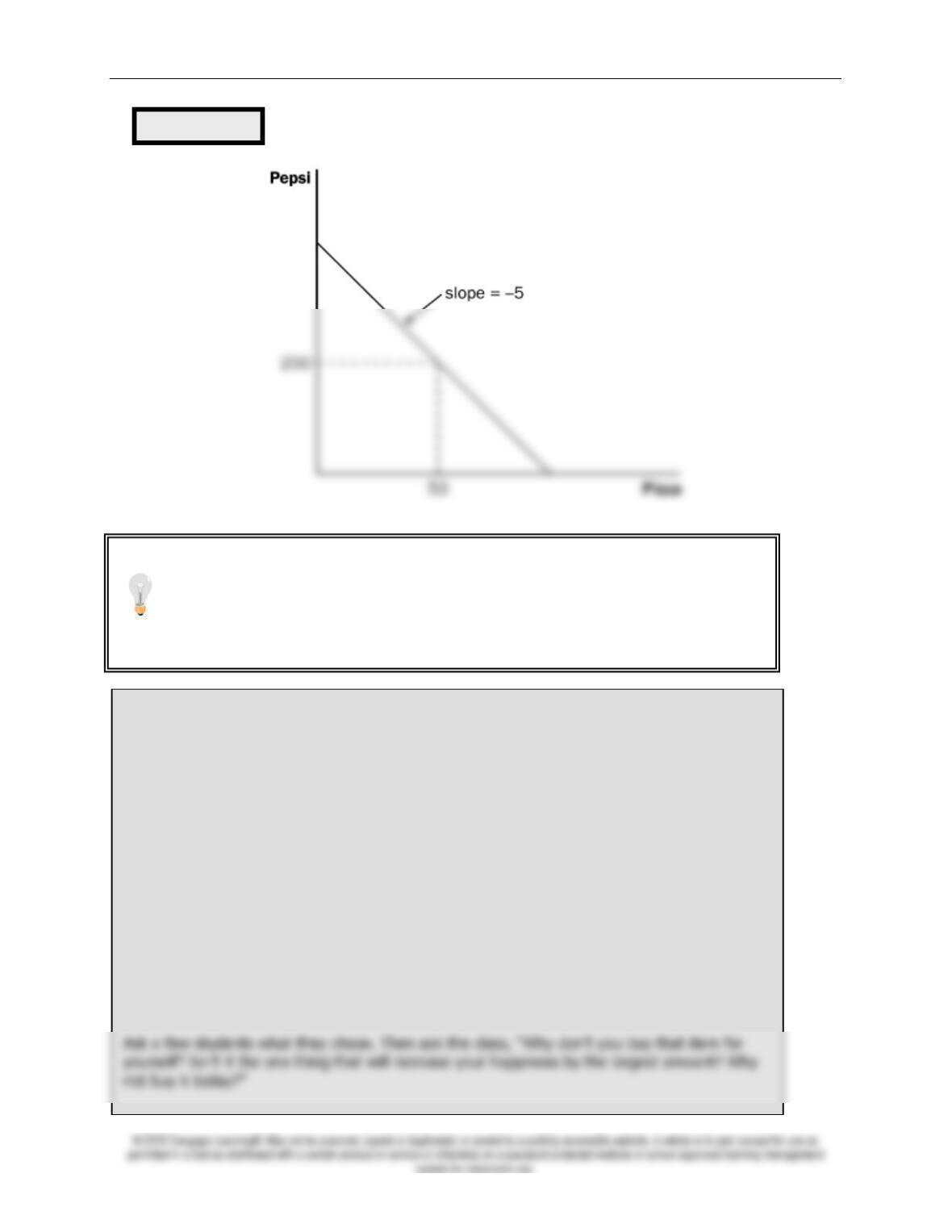

I. The Budget Constraint: What the Consumer Can Afford

A. Example: A consumer has an income of $1,000 per month to spend on pizza and Pepsi. The price

of a pizza is $10 and the price of a liter of Pepsi is $2.

D. Using this information, we can draw the consumer's budget constraint.

a. The slope of the budget constraint measures the rate at which the consumer can trade

one good for another.

b. The slope of the budget constraint equals the relative price of the two goods (1 pizza can

be traded for 5 liters of Pepsi).

This chapter is an advanced treatment of consumer choice using indifference curve

analysis. This chapter is much more difficult than the other chapters in the text. Most

undergraduate principles students will find this material challenging.

The best way to develop this model is to use specific examples with definite

quantities, prices, and levels of income.