Lecture Notes

Introduction

An immense amount of economic data is gathered on a regular basis. Every day, newspapers,

radio, television, and the Internet inform us about some economic statistic or other. Although we

cannot discuss all these data here, it is important to be familiar with some of the most important

measures of economic performance.

2-1 Measuring the Value of Economic Activity: Gross Domestic Product

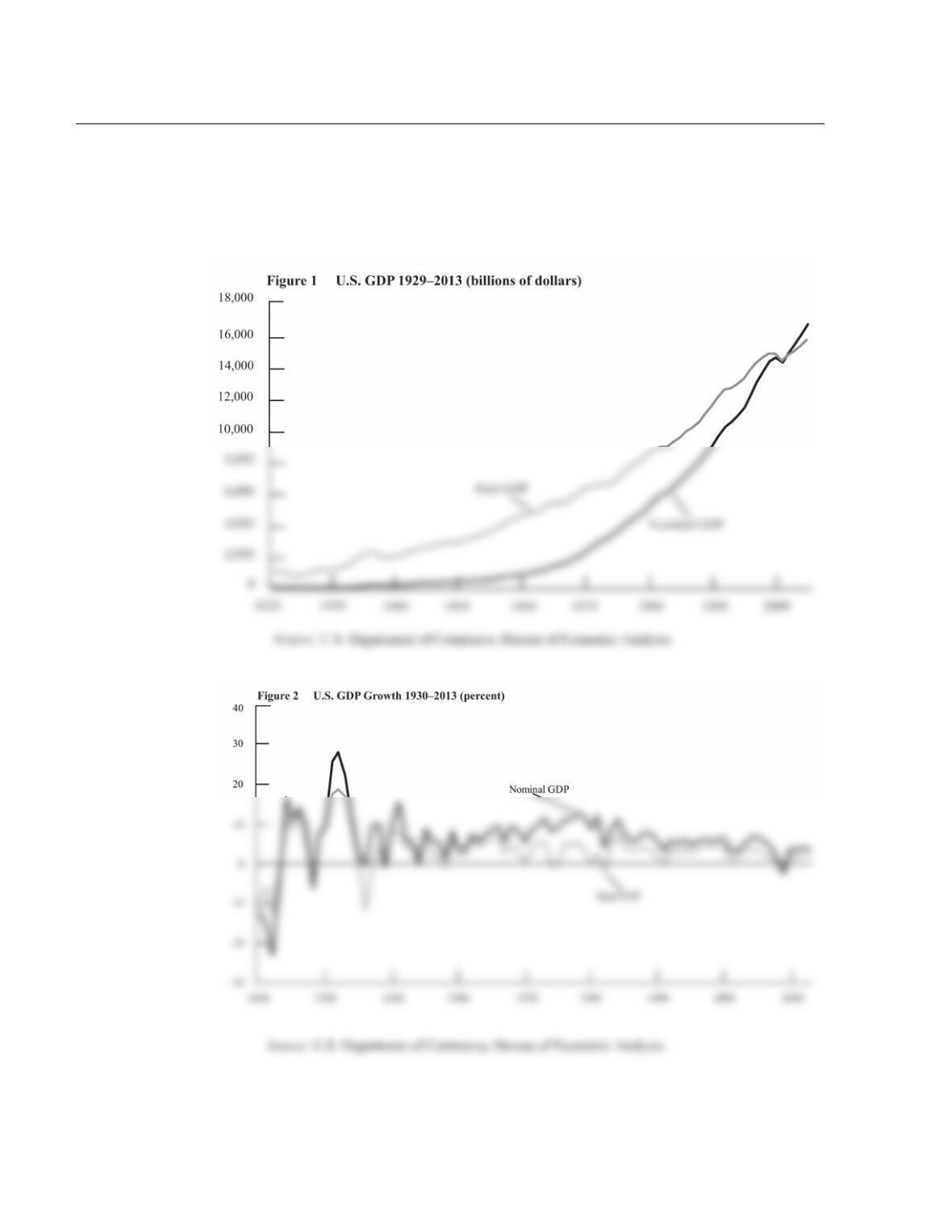

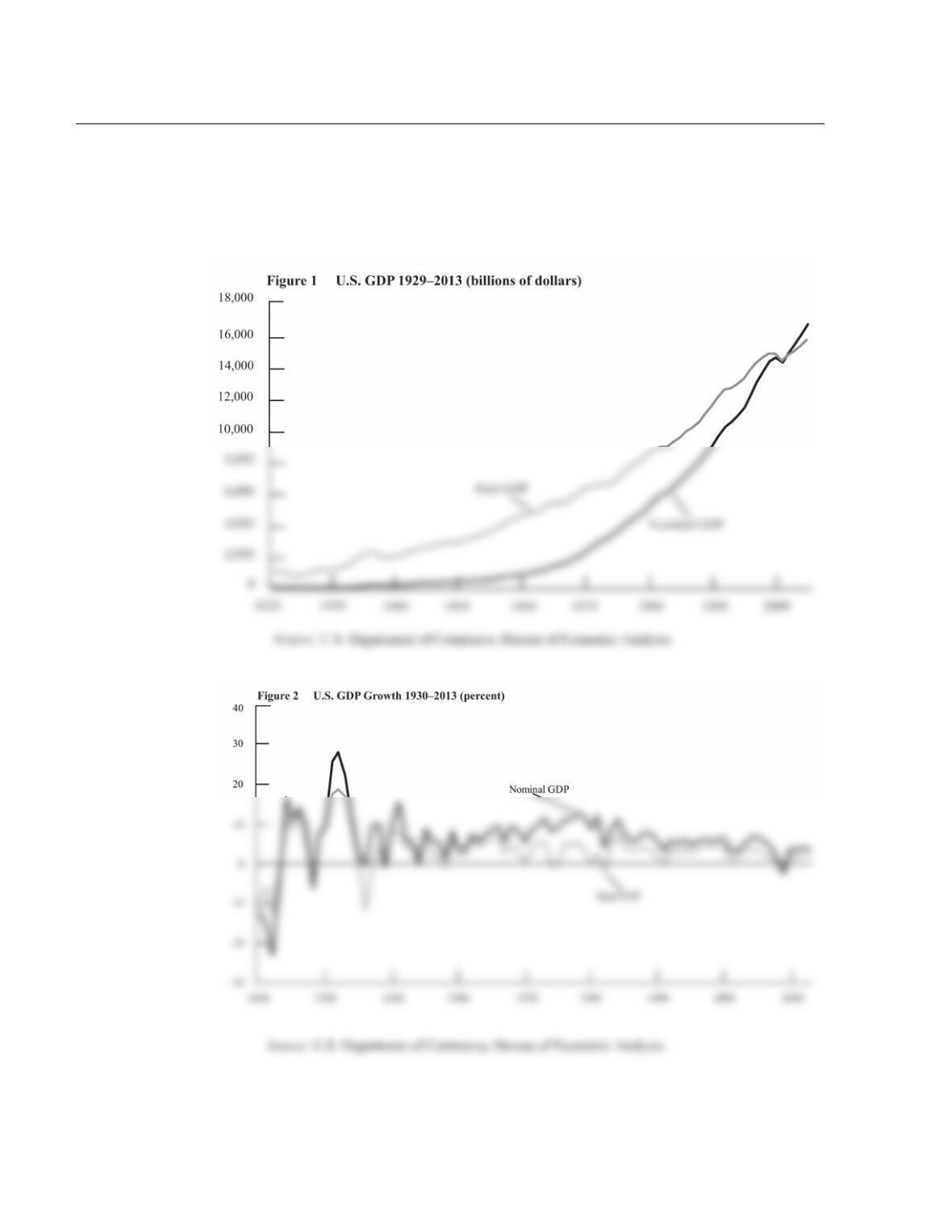

The single most important measure of overall economic performance is Gross Domestic Product

(GDP), which aims to summarize all economic activity over a period of time in terms of a single

number. GDP is a measure of the economy’s total output and of total income. Macroeconomists

Income, Expenditure, and the Circular Flow

Suppose that the economy produces just one good—bread—using labor only. (Notice what we

are doing here: We are making simplifying assumptions that are obviously not literally true to

gain insight into the working of the economy.) We assume that there are two sorts of economic

actors—households and firms (bakeries). Firms hire workers from the households to produce

bread and pay wages to those households. Workers take those wages and purchase bread from

the firms. These transactions take place in two markets—the goods market and the labor market.

FYI: Stocks and Flows

Goods are not produced instantaneously—production takes time. Therefore, we must have a

period of time in mind when we think about GDP. For example, it does not make sense to say a

bakery produces 2,000 loaves of bread. If it produces that many in a day, then it produces 4,000

in two days, 10,000 in a (five-day) week, and about 130,000 in a quarter. Because we always

have to keep a time dimension in mind, we say that GDP is a flow. If we measured GDP at any

tiny instant of time, it would be almost zero.

Rules for Computing GDP

Naturally, the measurement of GDP in the economy is much more complicated in practice than

our simple bread example suggests. There are any number of technical details of GDP

measurement that we ignore, but a few important points should be mentioned.

First, what happens if a firm produces a good but does not sell it? What does this mean for

GDP? If the good is thrown out, it is as if it were never produced. If one fewer loaf of bread is