411

ADVANCED TOPIC

17-5 Asset Pricing IV: Bubbles, Excess Volatility, and Fads

There are a number of dramatic historical incidents known as speculative bubbles, where the price of an

asset rises and falls dramatically. One of the most famous is Tulipmania: In the Netherlands in the

seventeenth century, certain rare varieties of tulip bulbs sold at extraordinarily high prices. “For example,

a Semper Augustus bulb sold for 2,000 guilders in 1625, an amount of gold worth about $16,000 at $400

per ounce.”1 At the end of 1636 and the beginning of 1637, tulip bulb prices rose very rapidly and then

collapsed suddenly; two years later, bulbs were selling for less than 0.1 guilder. Another famous example

is the South Sea Bubble, during which the price of shares in the South Sea Company rose more than

eightfold between January and July 1720 and then fell back to about their original level in the next three

months.2 In these cases, it seems that the price of an asset changes not because of a change in the

fundamentals but because investors demand the asset in the anticipation of future price rises, brought

about in turn by more investors demanding the asset in the expectation of still further price rises, and so

on.3 These incidents make many economists skeptical of the purported efficiency of financial markets.

Further evidence of inefficiency is the observation that asset prices are much too variable to be

explained in terms of changes in fundamentals.4 The economist Robert Shiller is a strong proponent of this

view. Informal evidence of such excess volatility comes from the observation of major variation in asset

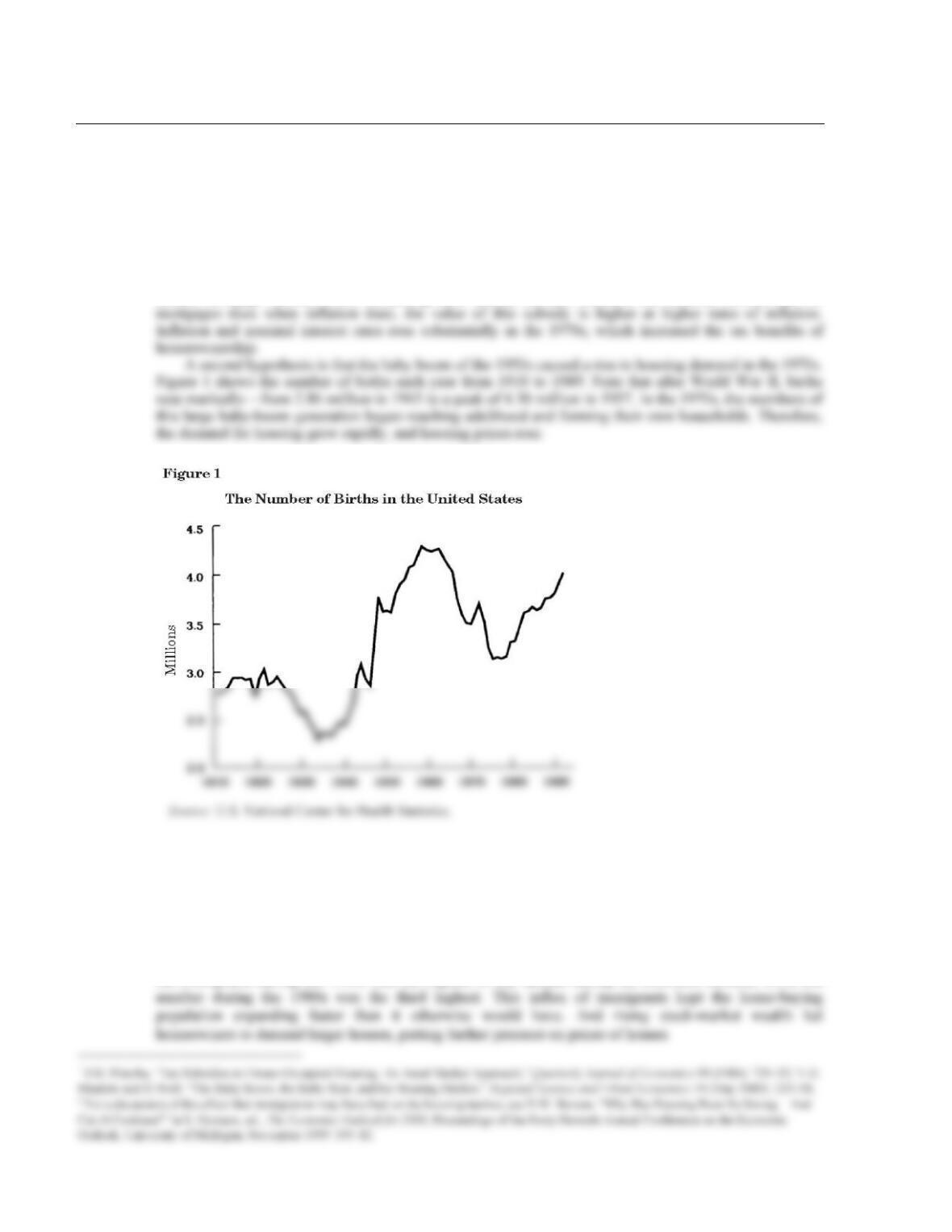

prices, such as the stock market crash of October 1987 or the recent movements in real estate prices in

some parts of the United States. Shiller and others have also provided more formal tests.

Shiller’s argument rests on a property of rational expectations and some simple statistics. He noted

that if the path of future dividends were known with certainty, then the perfect-foresight price of a stock

would be given by the present value of the stream of dividends.5 The actual price that investors are willing

to pay represents their prediction of this perfect-foresight price. If investors have rational expectations,

then the actual price will be the best possible forecast of the perfect-foresight price. The perfect-foresight

price then equals the actual price plus an unpredictable error term: