ADVANCED TOPIC

15-6 Real Business Cycles and Random Walks

Real business cycle theory provides a challenge to the traditional explanation of macroeconomic

fluctuations. One reason why this theory has been so influential is the work of two economists, Charles

Nelson and Charles Plosser.

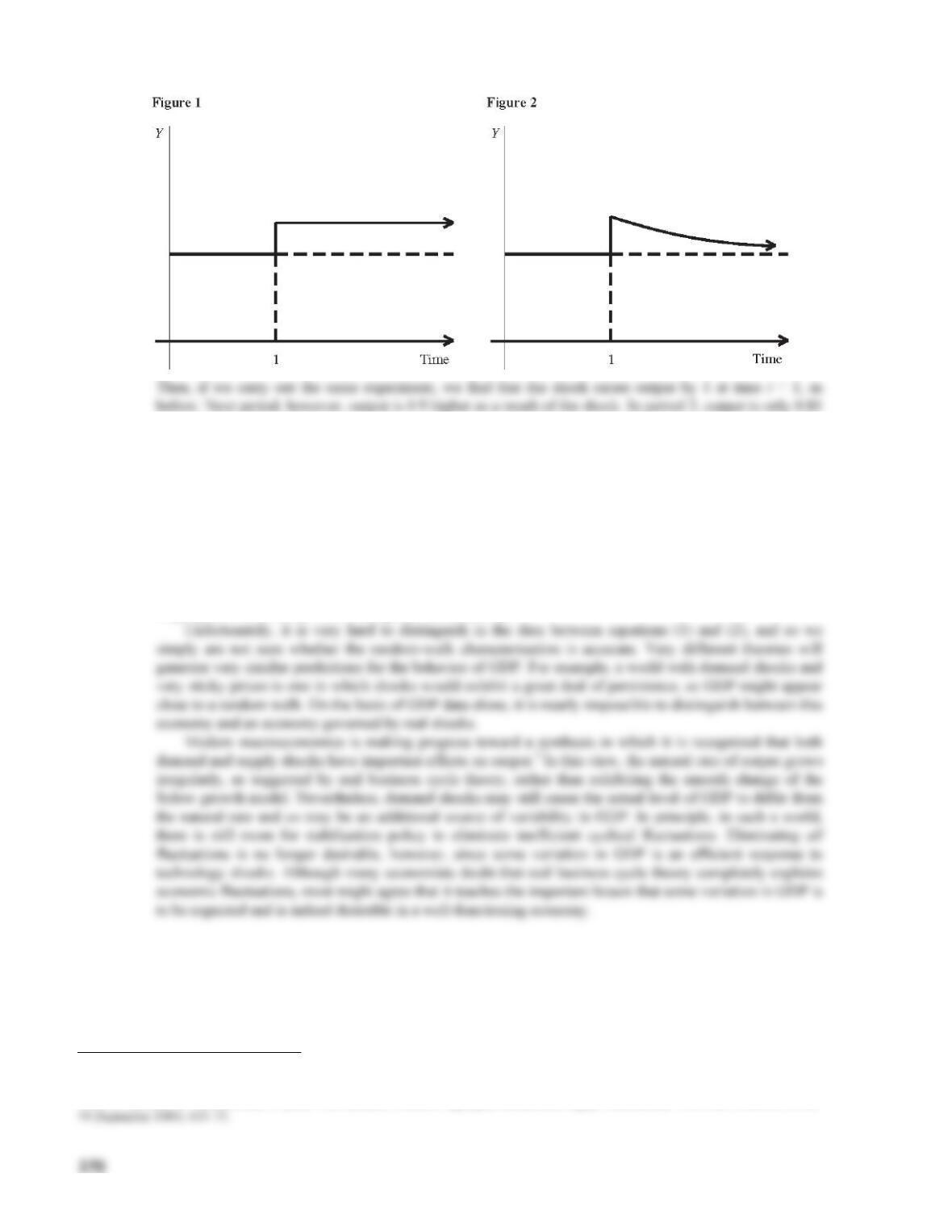

In an important article published in 1982, Nelson and Plosser argued that there is evidence to suggest

that U.S. GDP may follow a random walk.1 That is, they suggested that the behavior of real GDP over

time could be described by the equation

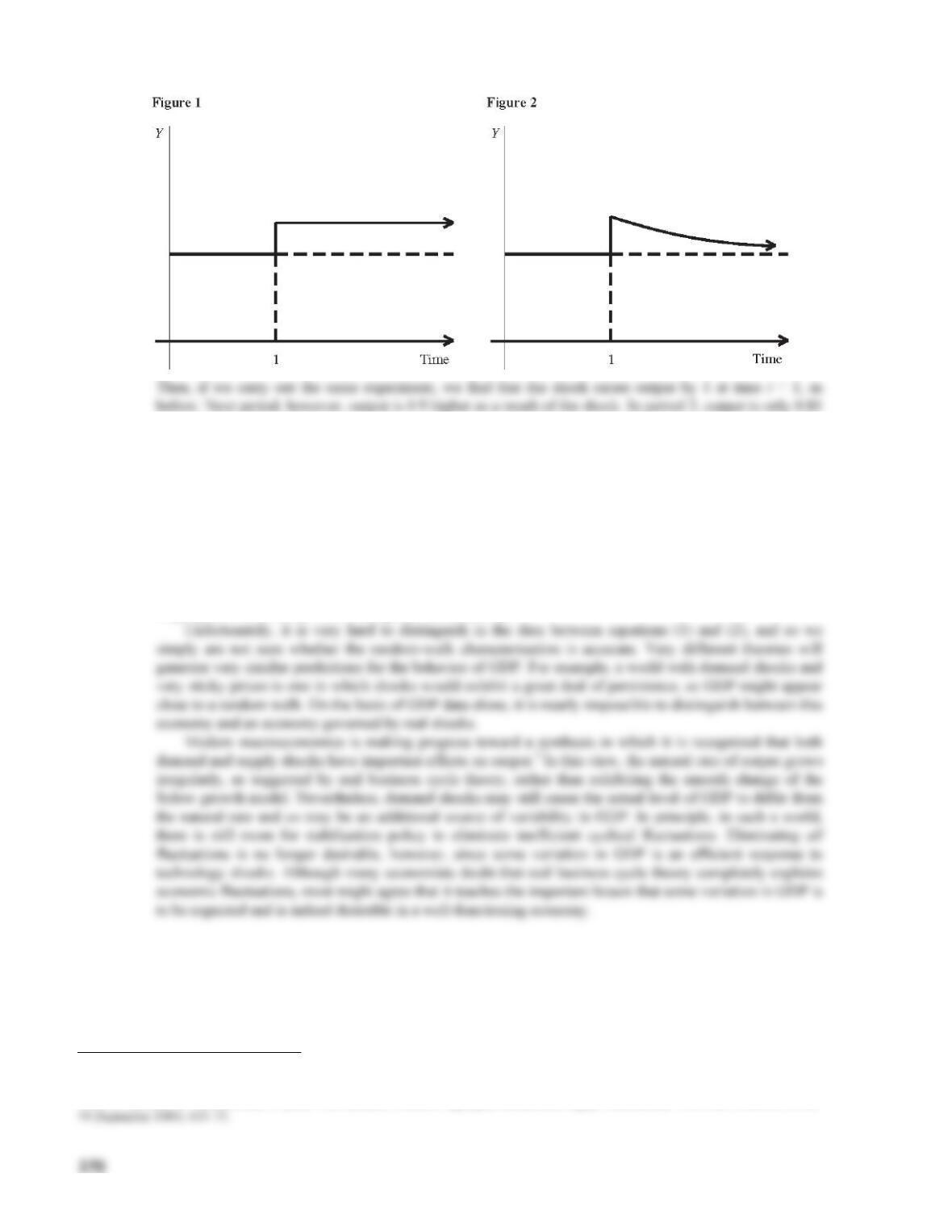

The conventional view of macroeconomic fluctuations is that the behavior of GDP over time can be

decomposed into a long-run natural-rate or trend component and a short-run cyclical component. This

approach underlies the models used in the textbook: The Solow growth model explains the long-run

behavior of the economy and the aggregate demand–aggregate supply model explains short-run

fluctuations. In this view, shocks to the economy will push it away from the natural rate only temporarily;

the economy always has a tendency to revert to the natural rate. But the Nelson–Plosser finding challenges

this characterization. If GDP does follow a random walk, then shocks to output have permanent effects.

To see this, suppose that at some time (t = 0), GDP is at the value Y0, and that at t = 1 there is a one-

unit shock to GDP (u1 = 1). Suppose also that there are no further shocks (u2 = u3 = . . . = 0). Then

Y1 = Y0 + 1.

Now

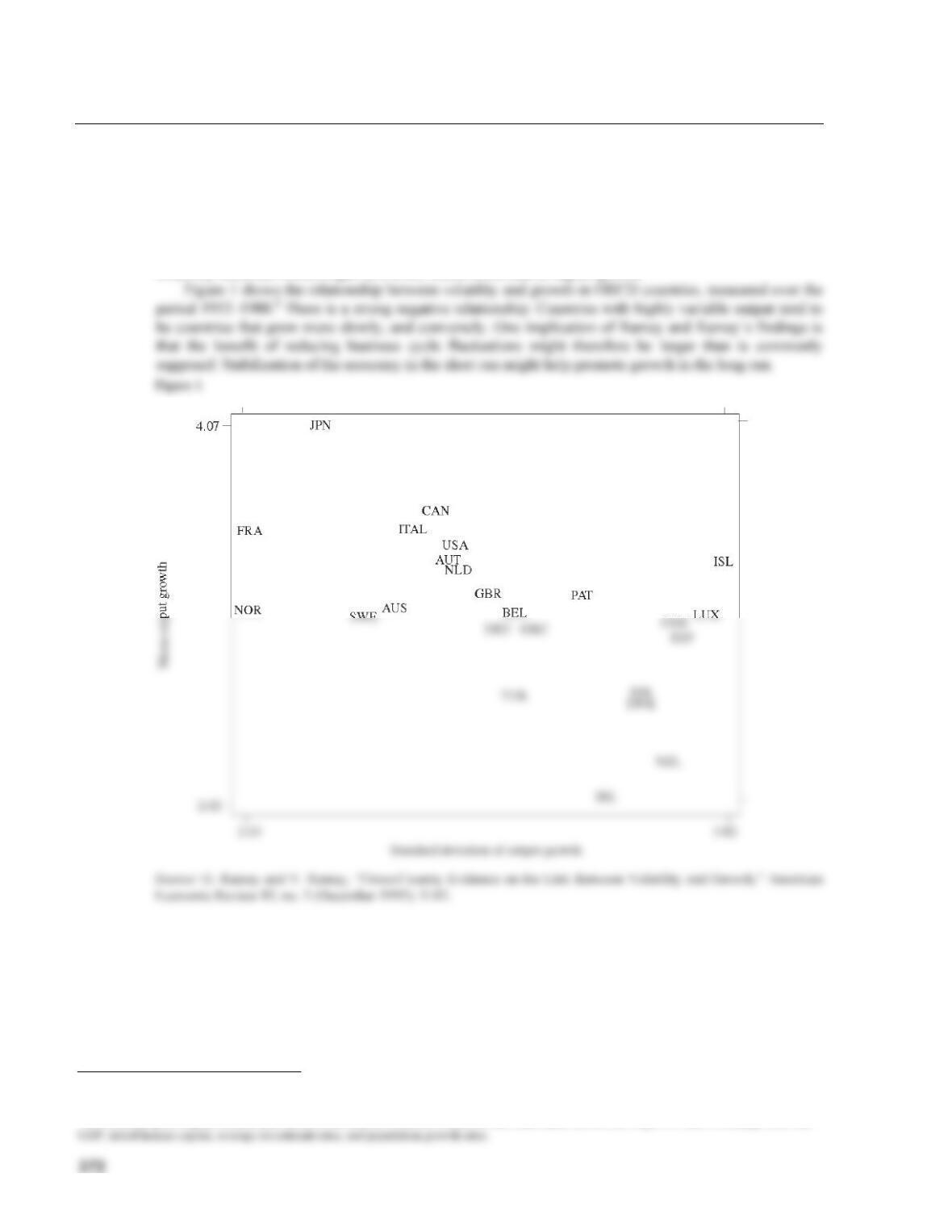

that technological progress is irregular and a source of fluctuations. Indeed, if this real business cycle

characterization of the data is accurate, then the traditional decomposition of output into cycle and trend

does not really make sense.

If GDP does not follow a random walk, then the conclusion is very different. Suppose, for example,

that the behavior of GDP can be described by the equation