CHAPTER 15

A Dynamic Model of Economic

Fluctuations

Notes to the Instructor

Chapter Summary

Part V of the text presents some advances in macroeconomic theory that clarify our

understanding of the economy. This part of the text begins with Chapter 15, which extends the

analysis of short-run fluctuations to consider the response over time of key macroeconomic

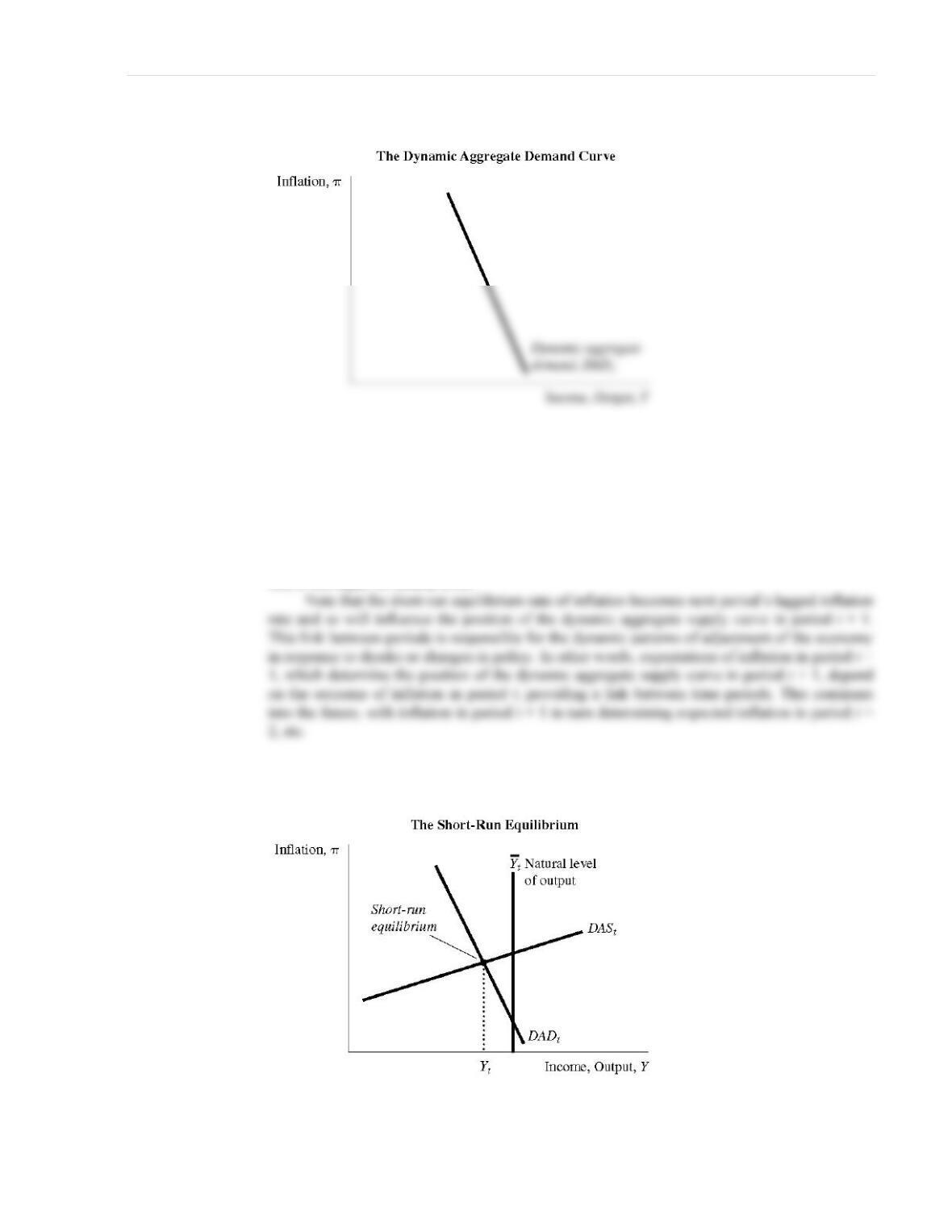

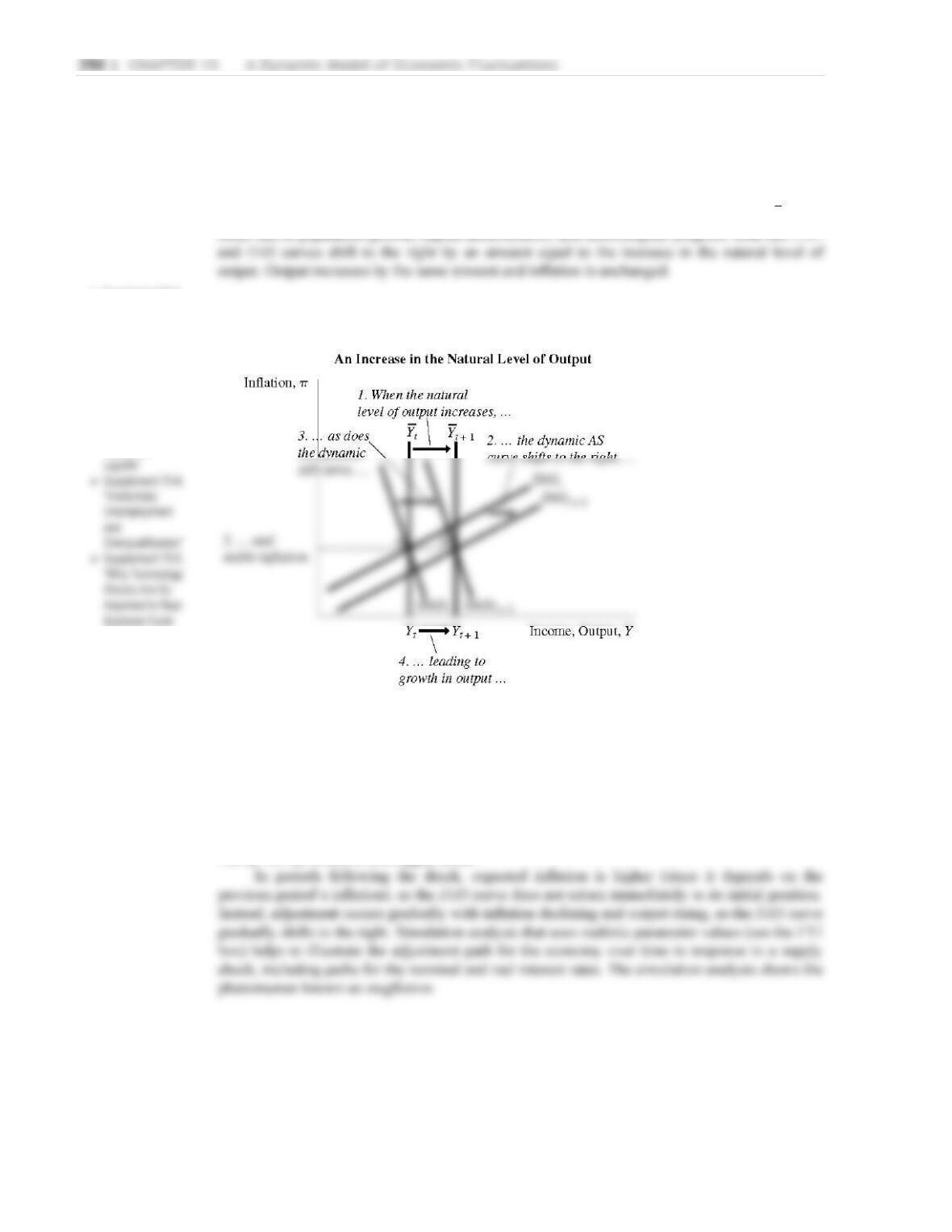

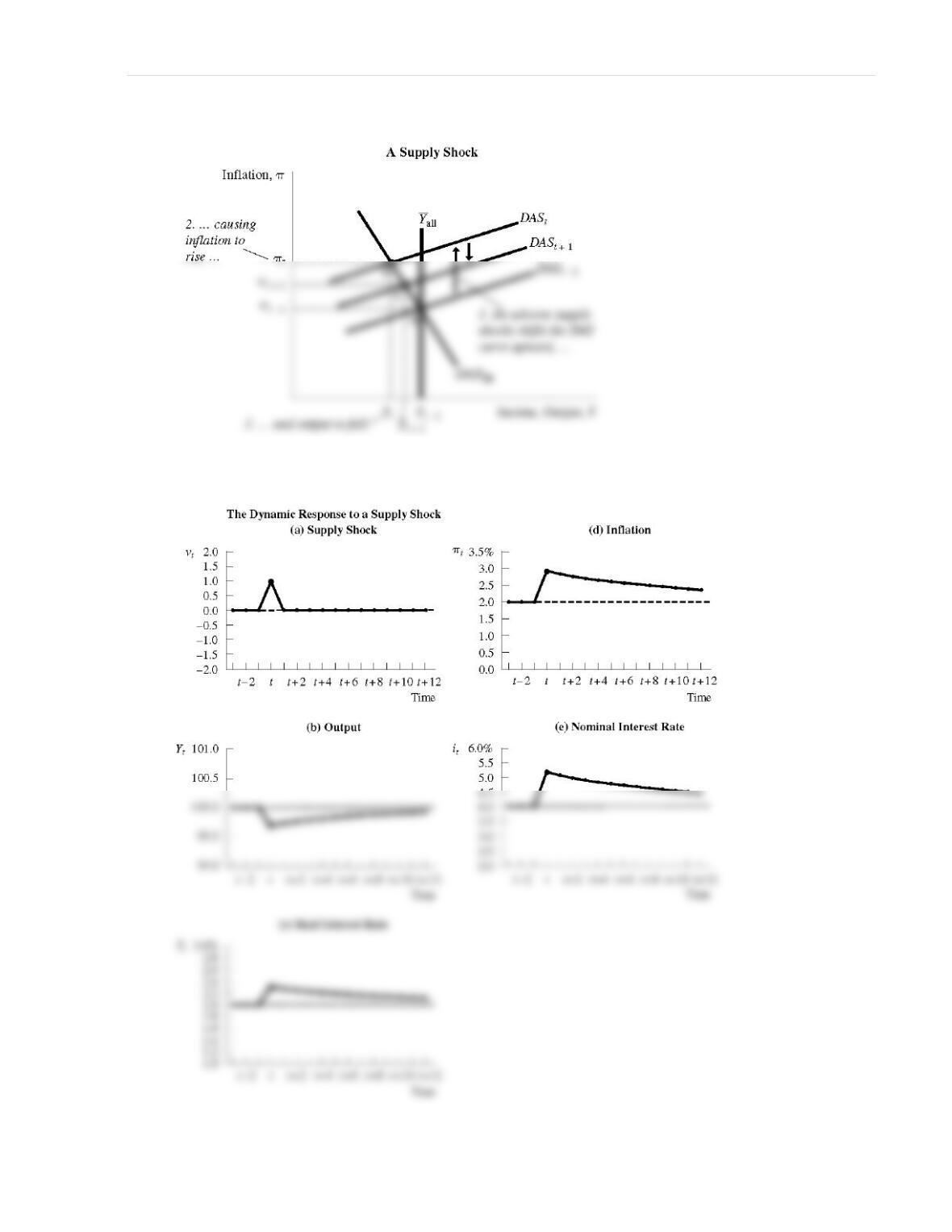

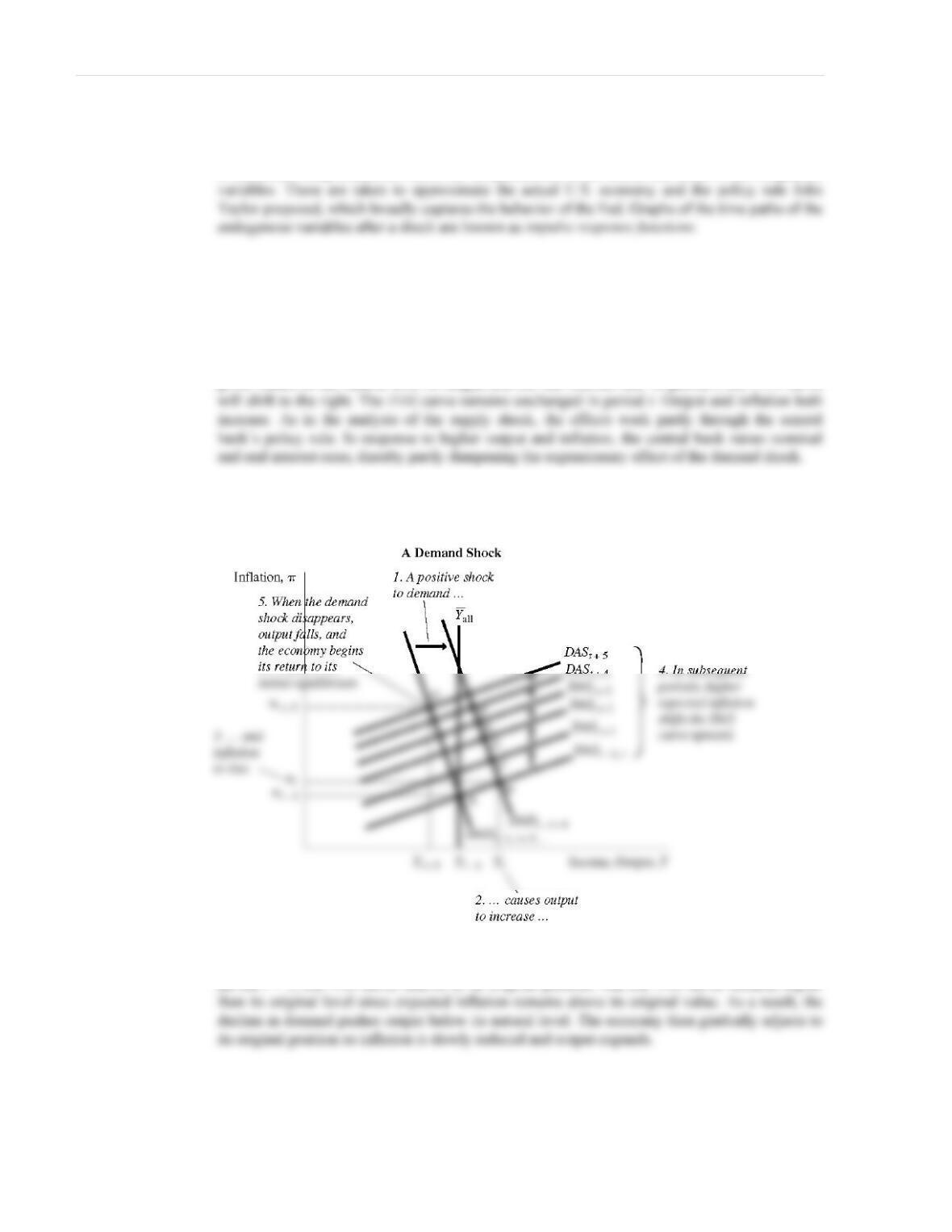

variables. The chapter does this by constructing a dynamic model of aggregate demand and

Comments

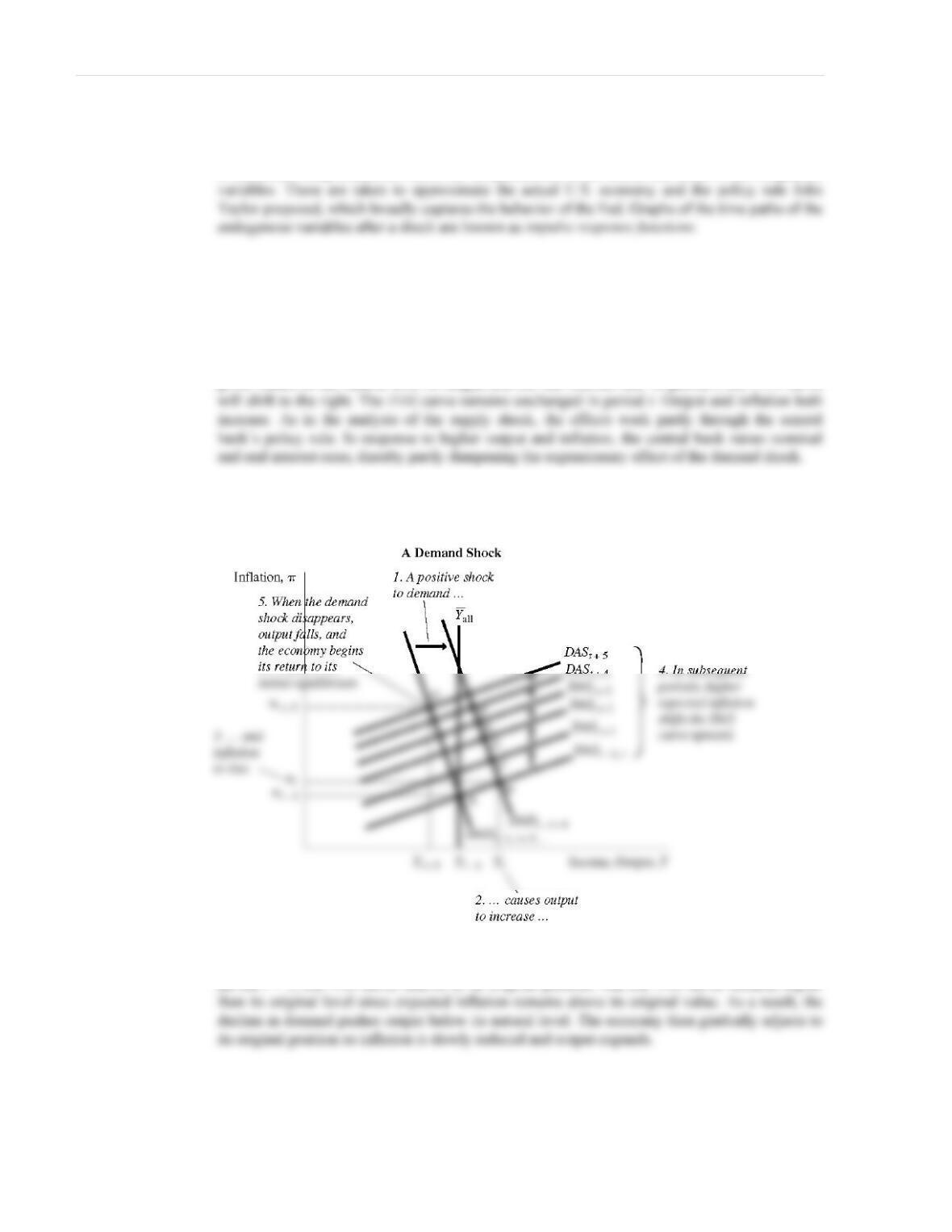

The material presented in this chapter is more difficult than the AD–AS, IS–LM models analyzed

in earlier chapters. But because many of the building blocks have already been discussed,

instructors should have a relatively easy time motivating the approach, and students should

readily see the connections to what they have already learned. The model consists of five

equations—a relatively large number for undergraduates to work with—but the discussion

surrounding the model requires only basic algebra. Dynamic solution of the model is done

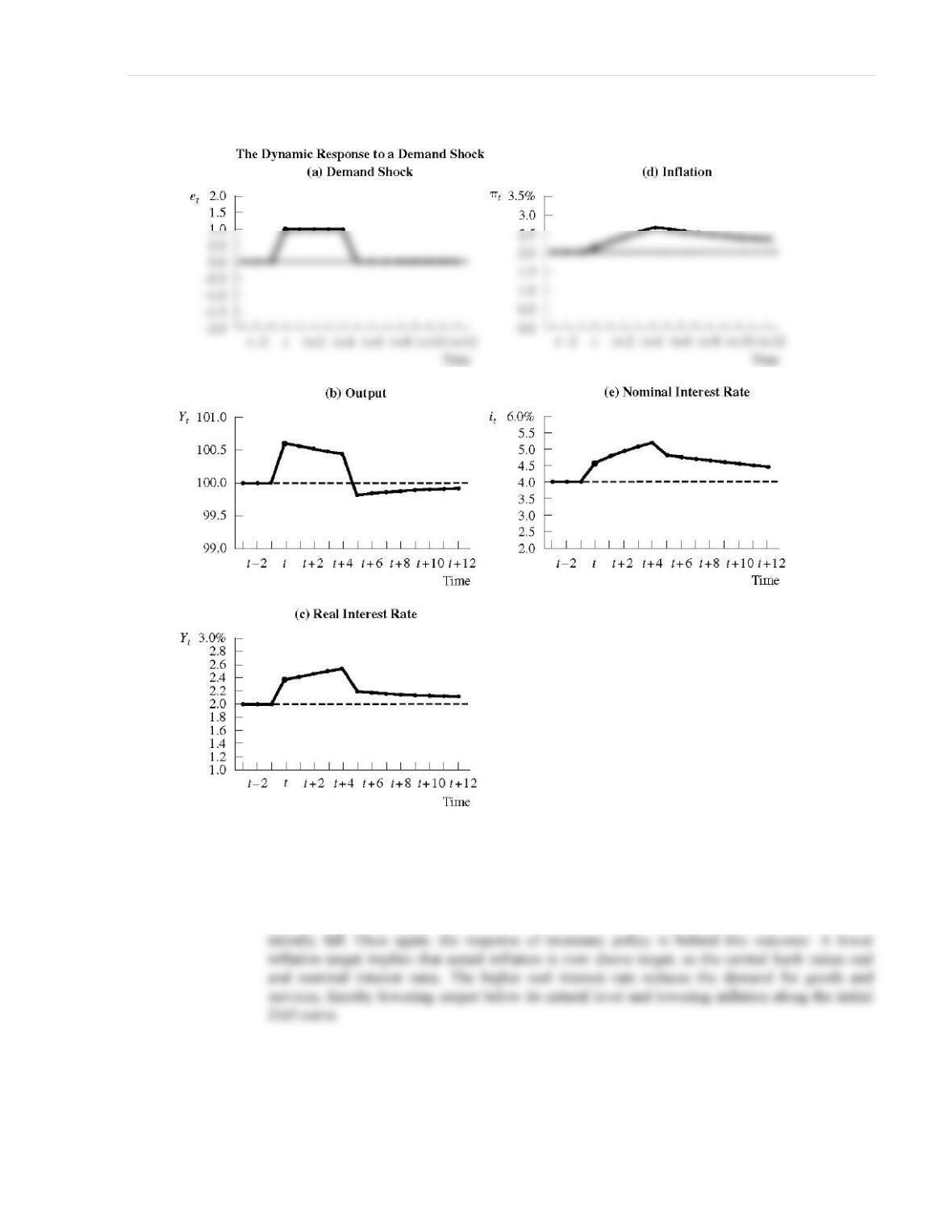

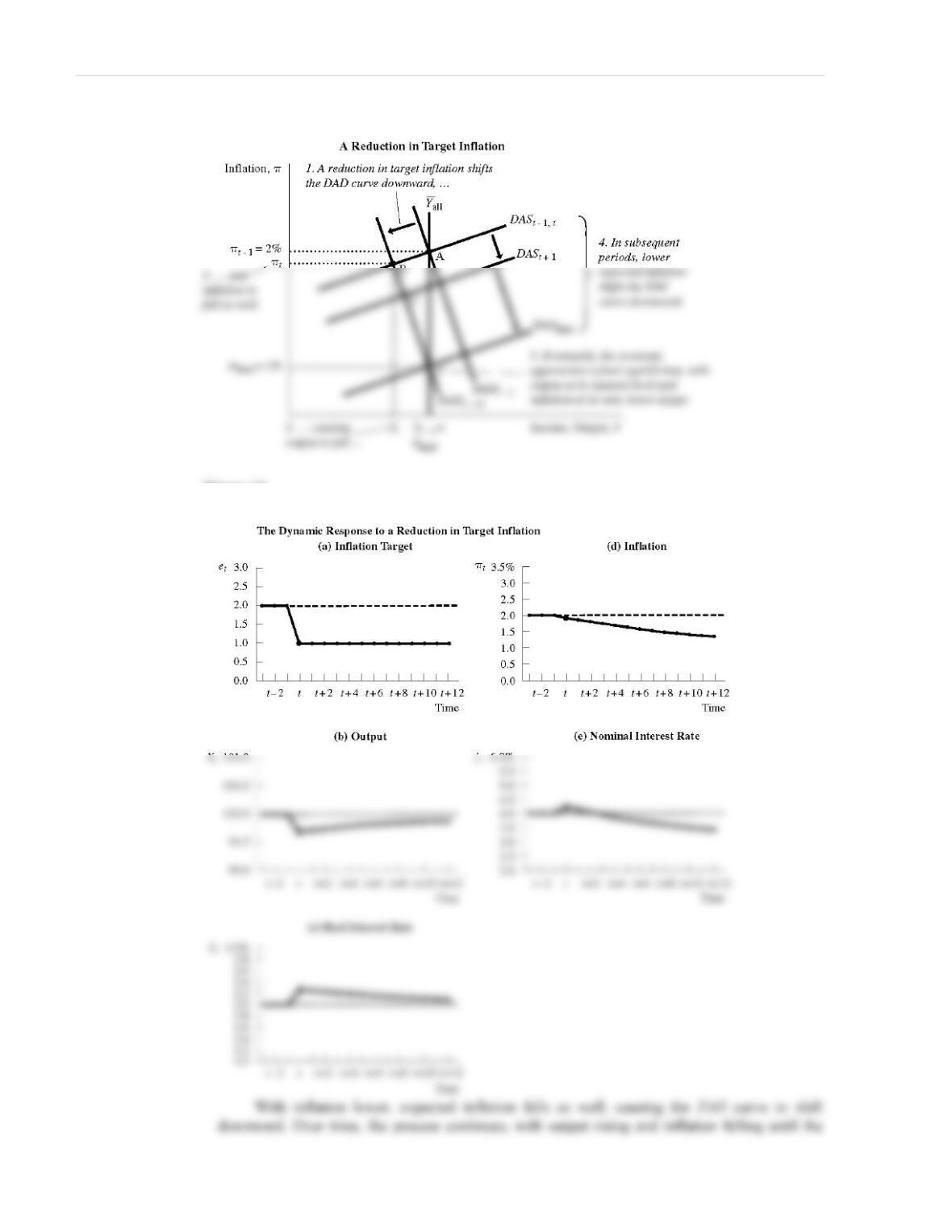

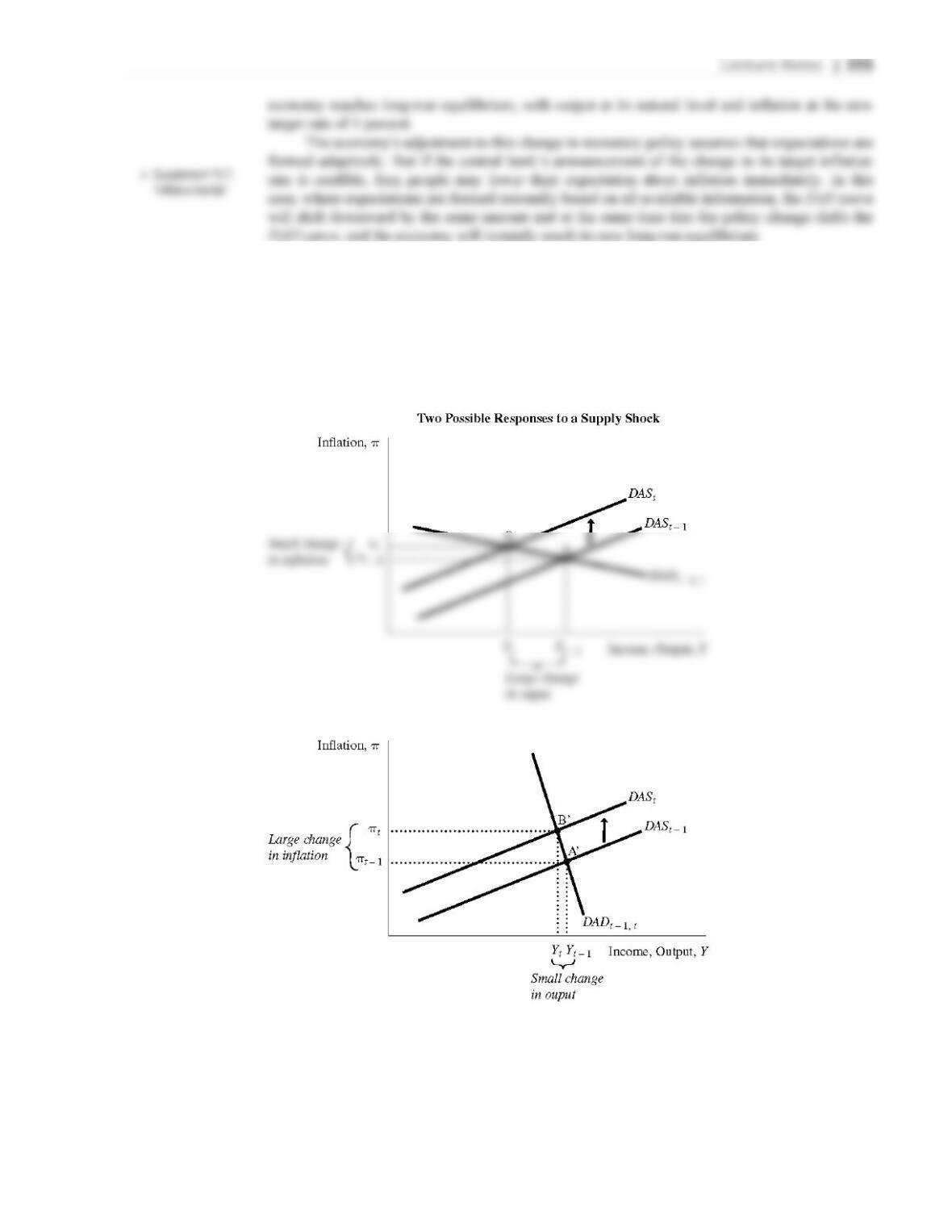

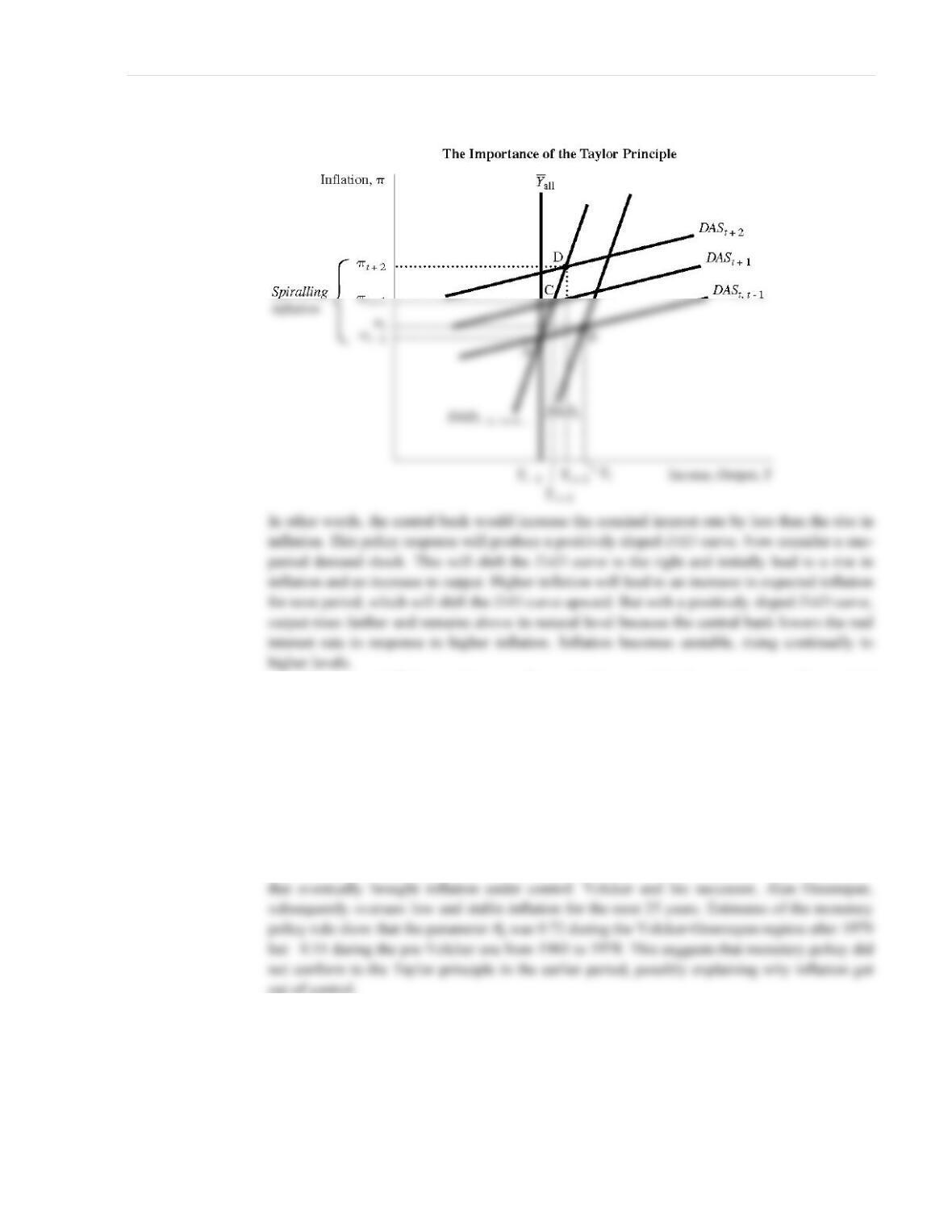

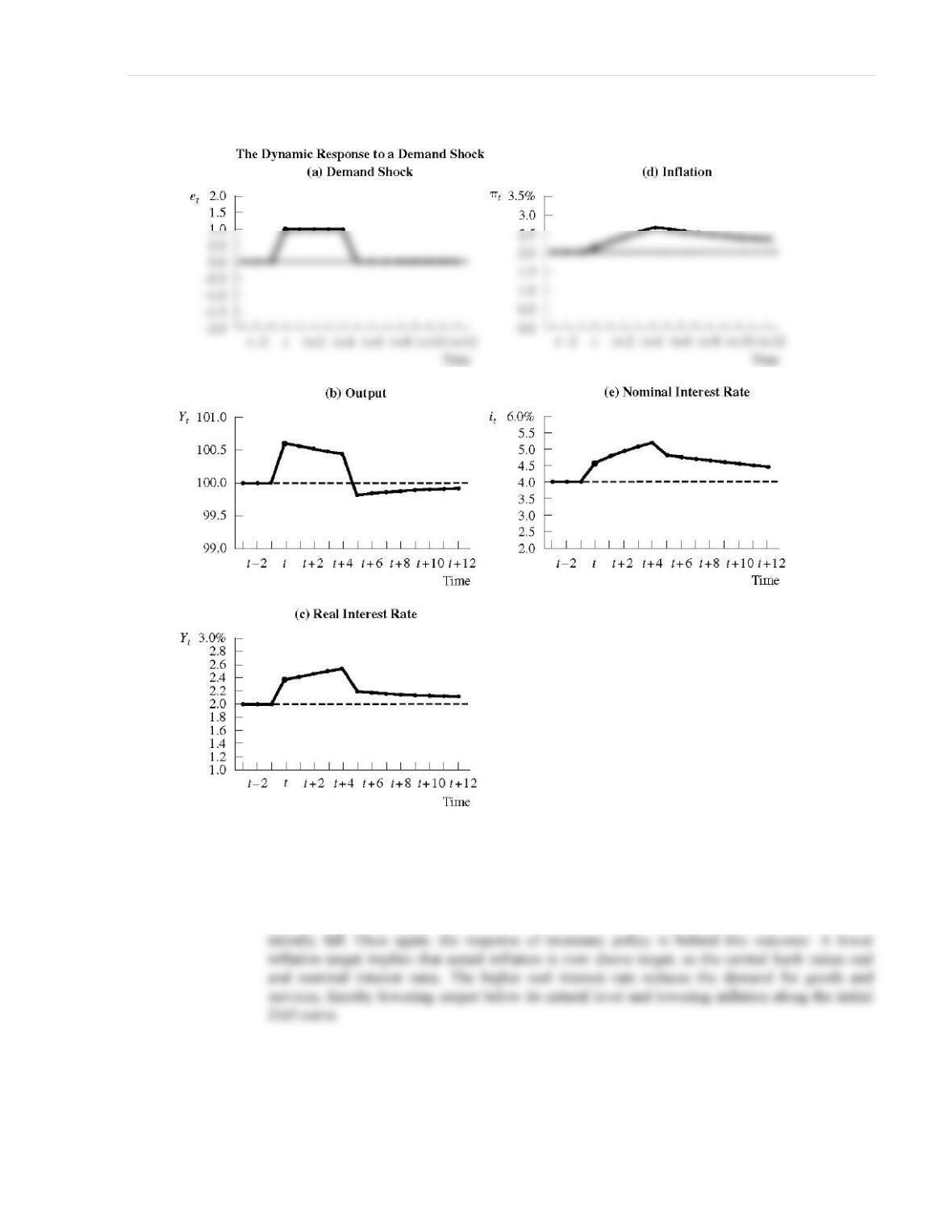

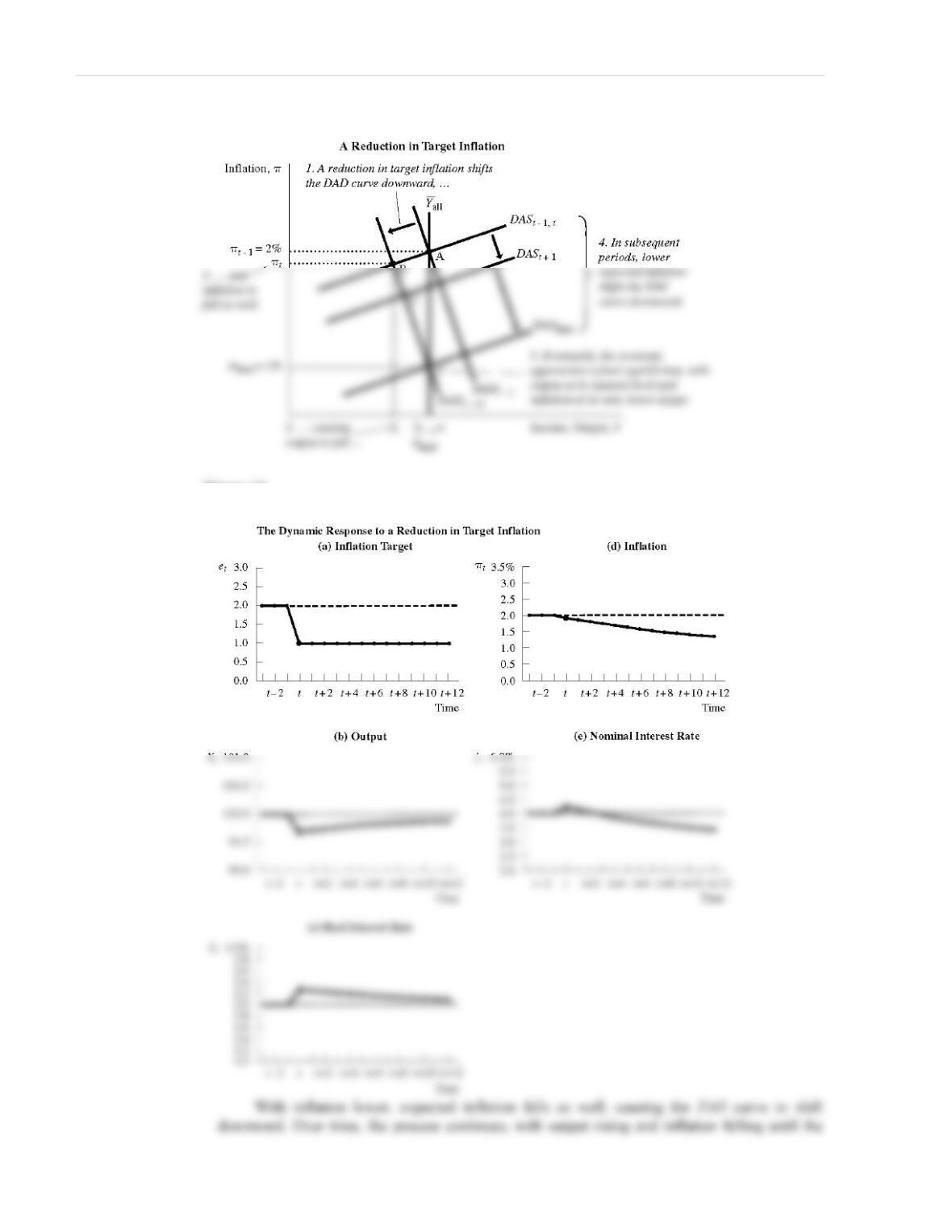

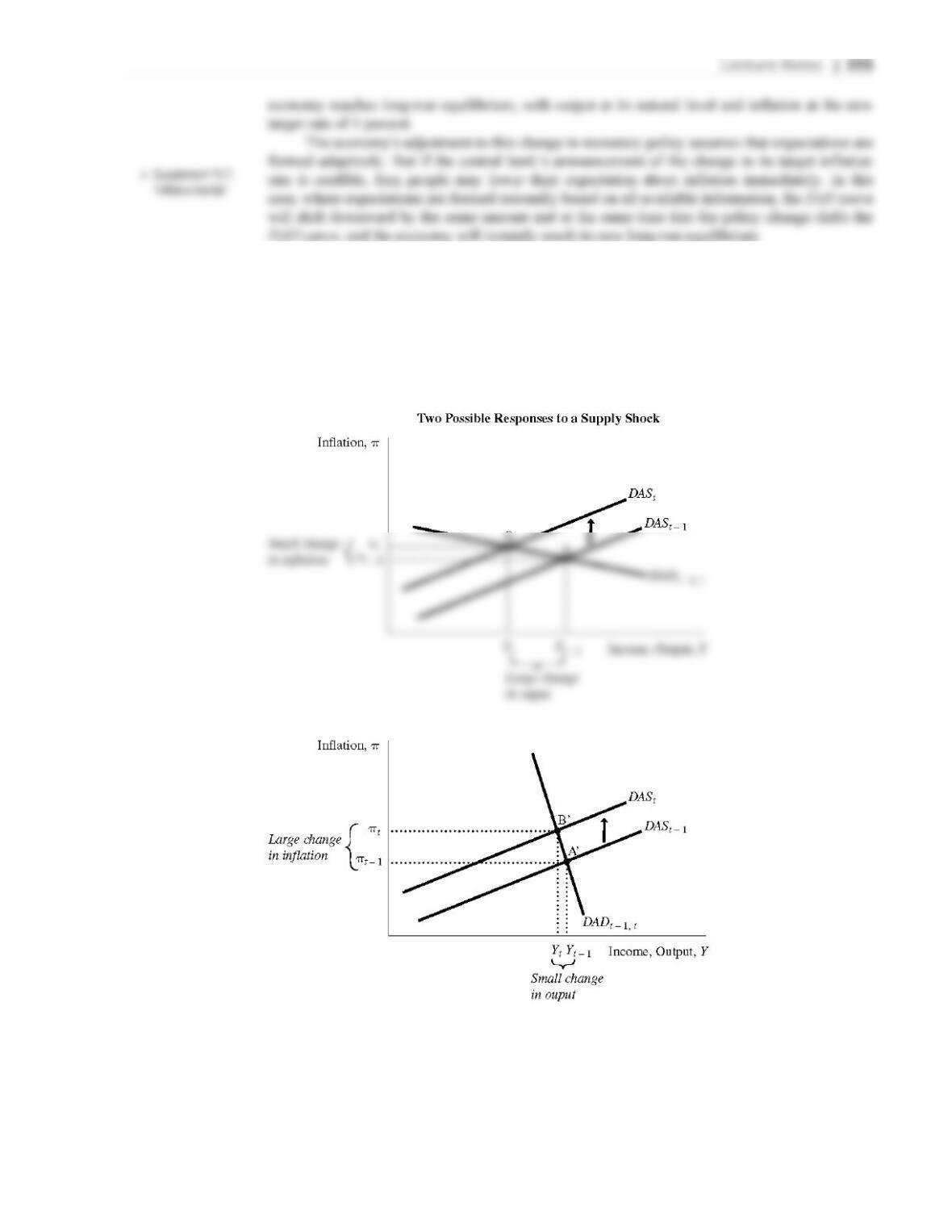

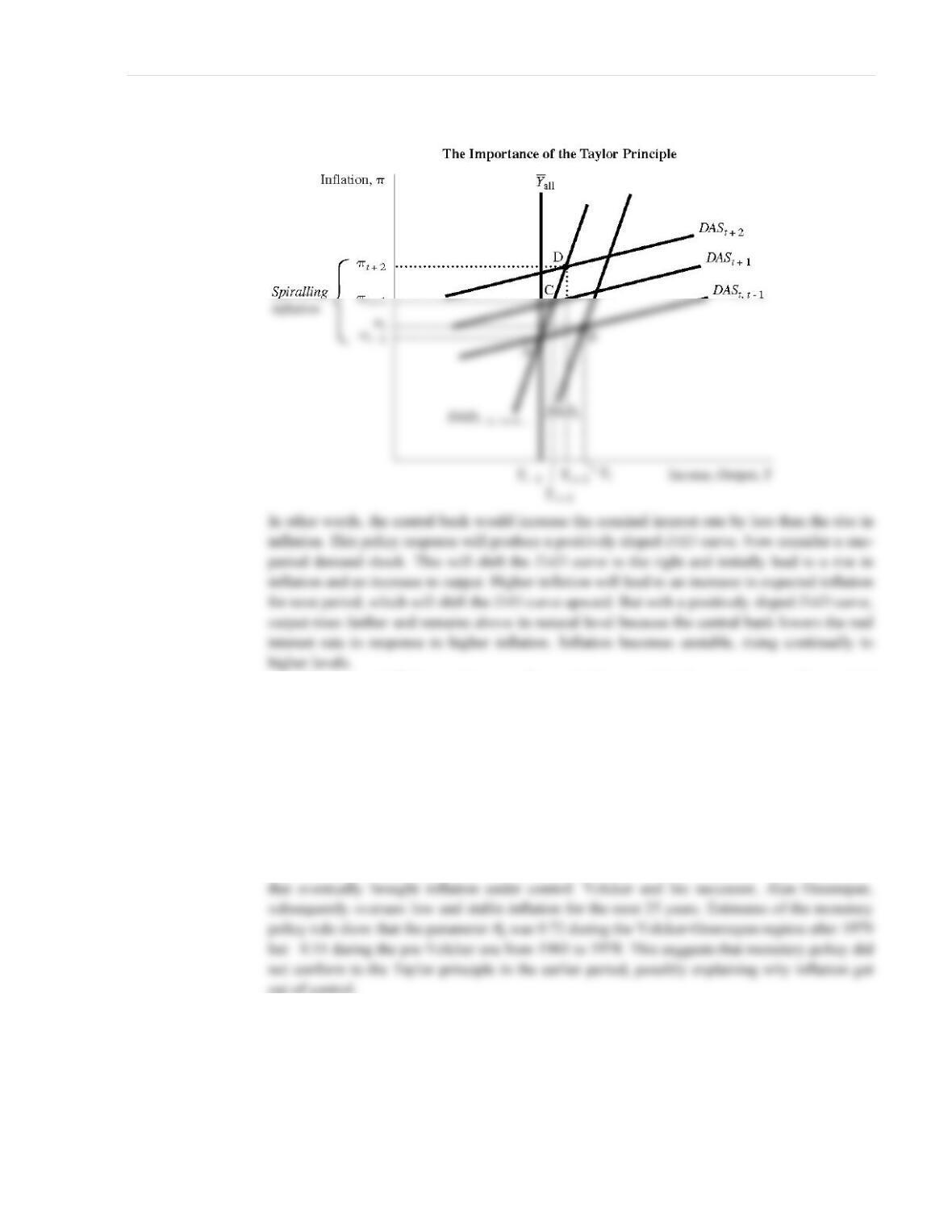

through simulation exercises, with figures illustrating the time paths of different variables.

Faculty who don’t feel comfortable with going through the algebra of the model’s details can

still use the chapter effectively by relying on the simulation figures to discuss how various

shocks and changes in policy affect the economy over time.

Use of the Dismal Scientist Web Site

Go to the Dismal Scientist Web site and download annual data on the federal funds rate, real

GDP, and the GDP price index over the past 30 years. Compute the trend level of real GDP over

time by graphing it and choosing as endpoints 1979 and 2006 (cyclical peaks). Now construct a

GDP gap series by subtracting your trend GDP from actual GDP. Compute the inflation rate

using the GDP price index. Using the specification of the Taylor rule discussed in Chapter 15,

compute predictions for the federal funds rate over this time period. Now compare your

predictions with the actual federal funds rate. When are they similar and when are they different?

Does the rule fit better after the shift in 1984 to interest-rate targeting and away from monetary-

aggregate targeting by the Federal Reserve? Assess whether your findings suggest that monetary