303

ADDITIONAL CASE STUDY

13-8 Interest Rate Differentials in the European Monetary System

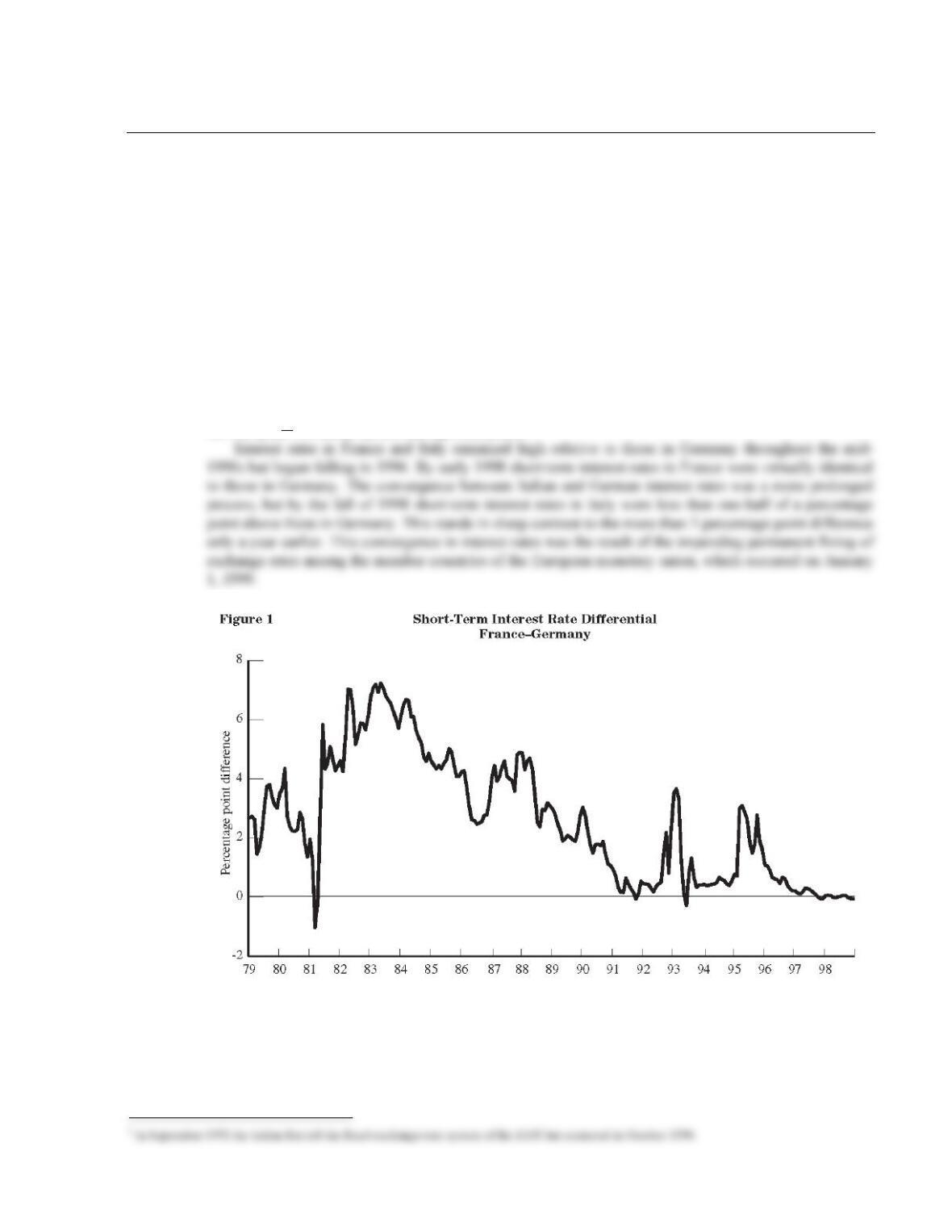

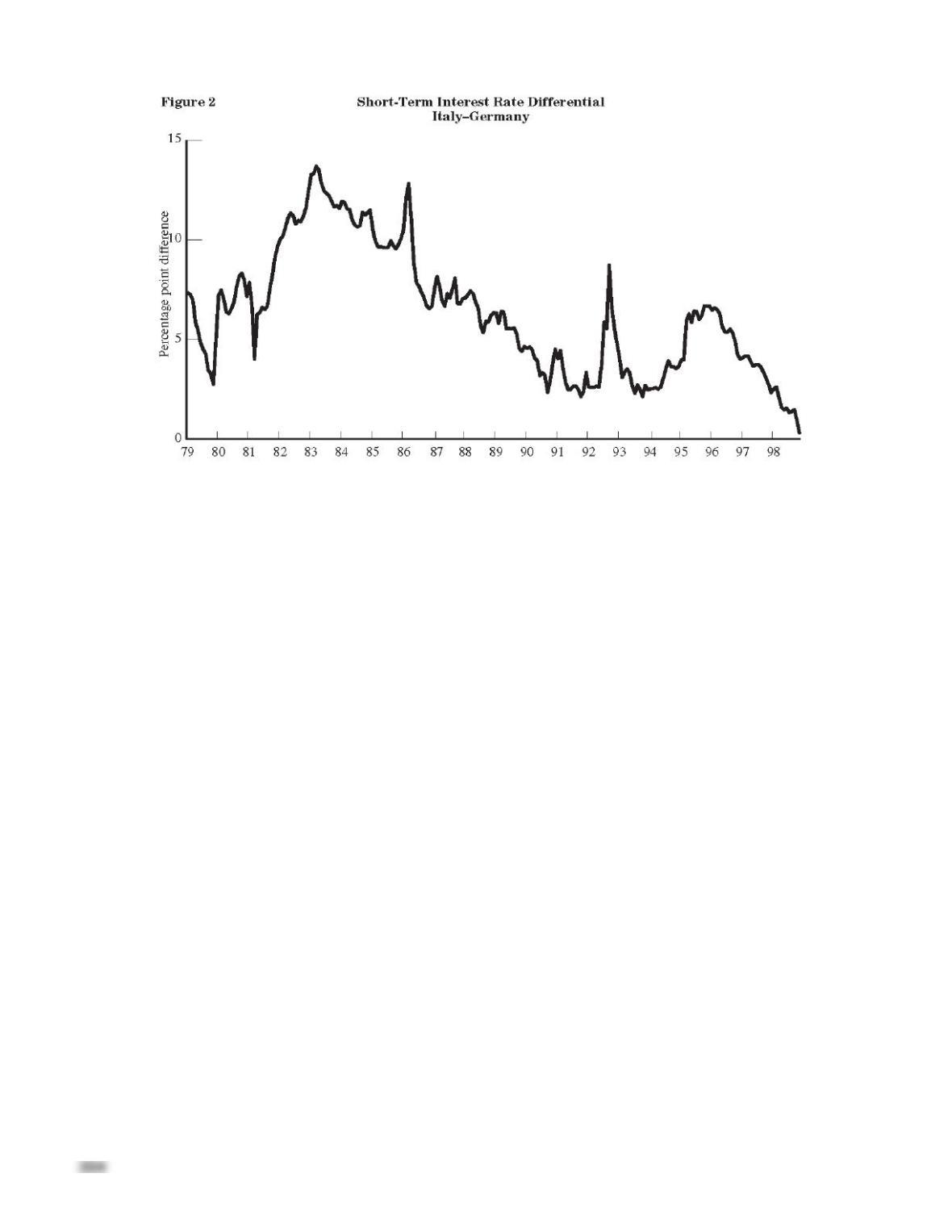

To the extent that interest-rate differences across countries reflect expectations about changes in exchange

rates, these differences can provide information about the credibility of a fixed-exchange-rate system. If

two countries fix the rate at which their currencies can be exchanged for each other and if individuals

believe that the exchange rate will not change, then interest rates in the two countries should be identical.

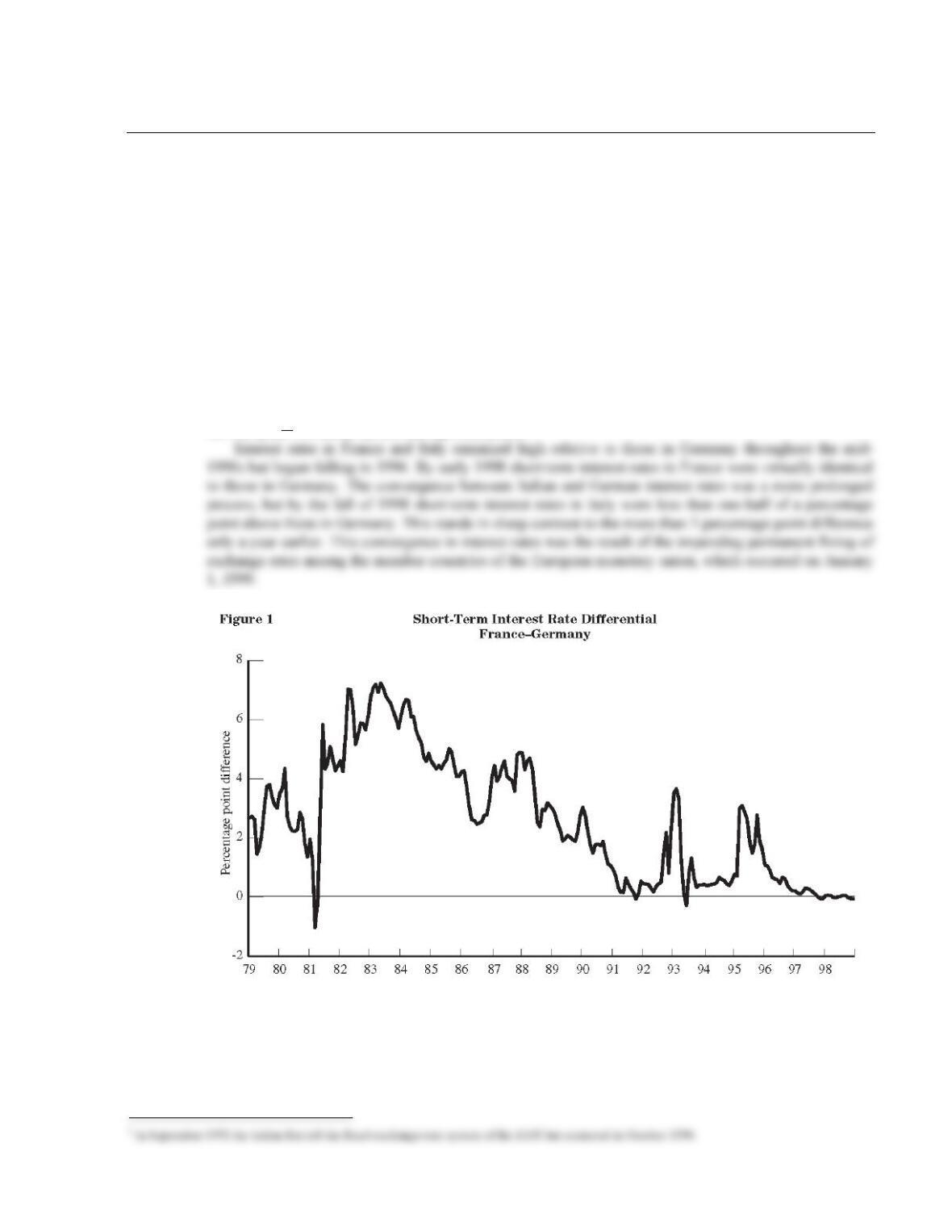

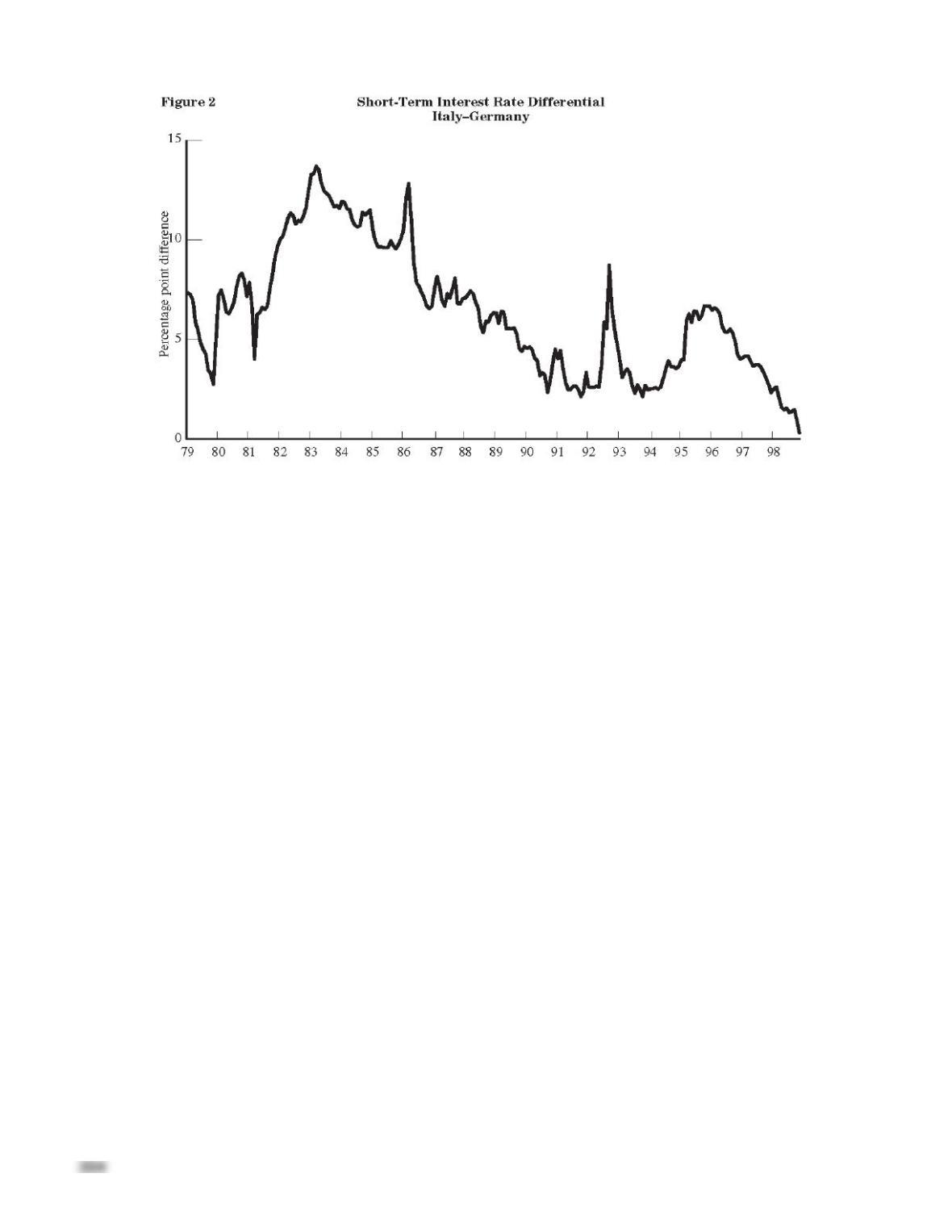

In 1979 several members of the European Union fixed their exchange rates. Each country’s currency

was allowed to fluctuate only within narrow bands against the currencies of the other members of the

exchange-rate mechanism of the European Monetary System. Interest-rate differences between the

countries indicate changes in the credibility of the exchange-rate system. Figures 1 and 2 show the

differences between short-term (three-month) interest rates in France and Germany and short-term interest

rates in Italy and Germany. Throughout the 1980s the exchange rate system became more credible, and

individuals became increasingly convinced that the exchange rates would be maintained. By the beginning

of 1991, for example, French and German interest rates differed by less than 1 percentage point. In 1992

and 1993, however, interest rates in France and Italy rose relative to German rates, reflecting the crisis in

the European Monetary System during those years.11