156 ❖ Chapter 8 /Application: The Costs of Taxation

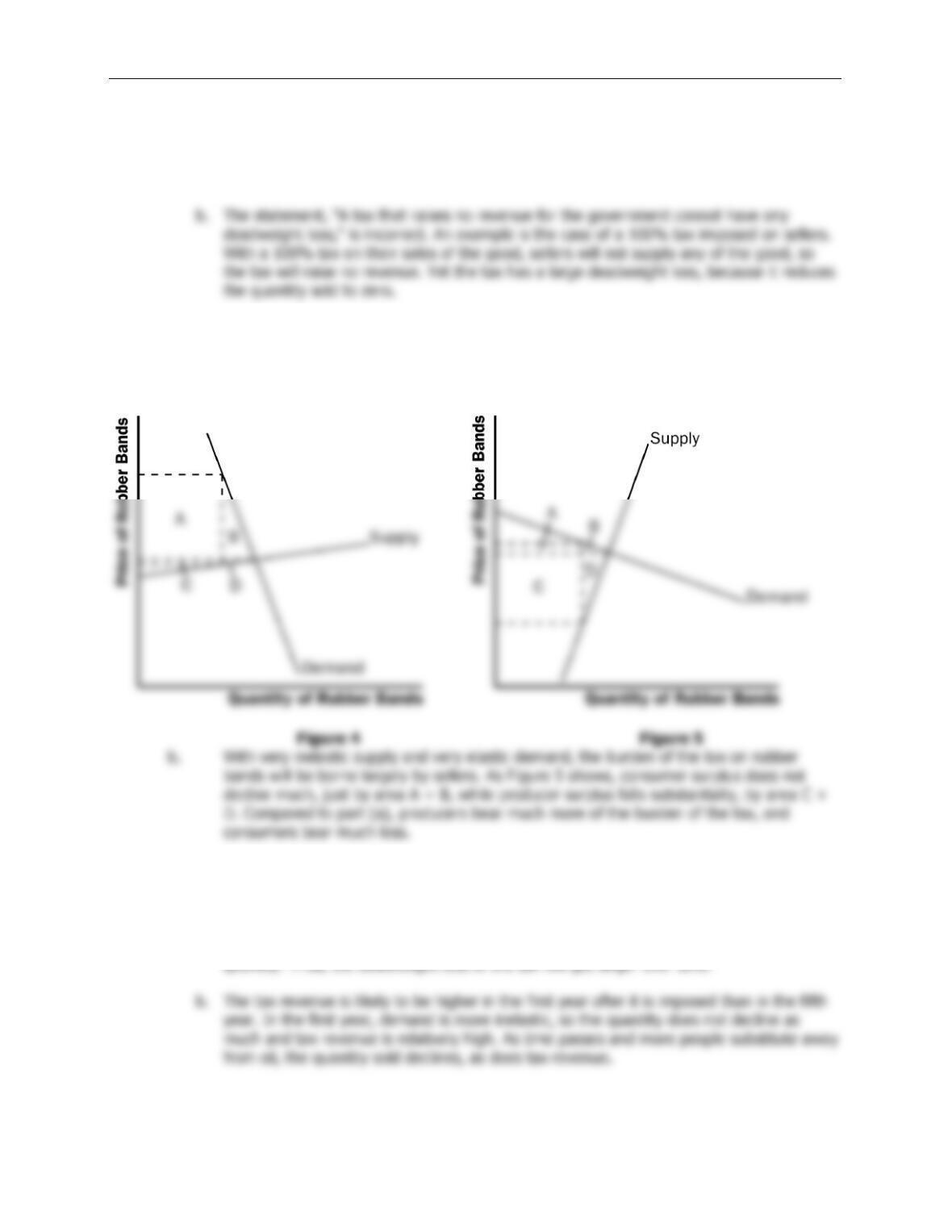

5. Because the demand for food is inelastic, a tax on food is a good way to raise revenue

because it does not lead to much of a deadweight loss; thus taxing food is less inefficient

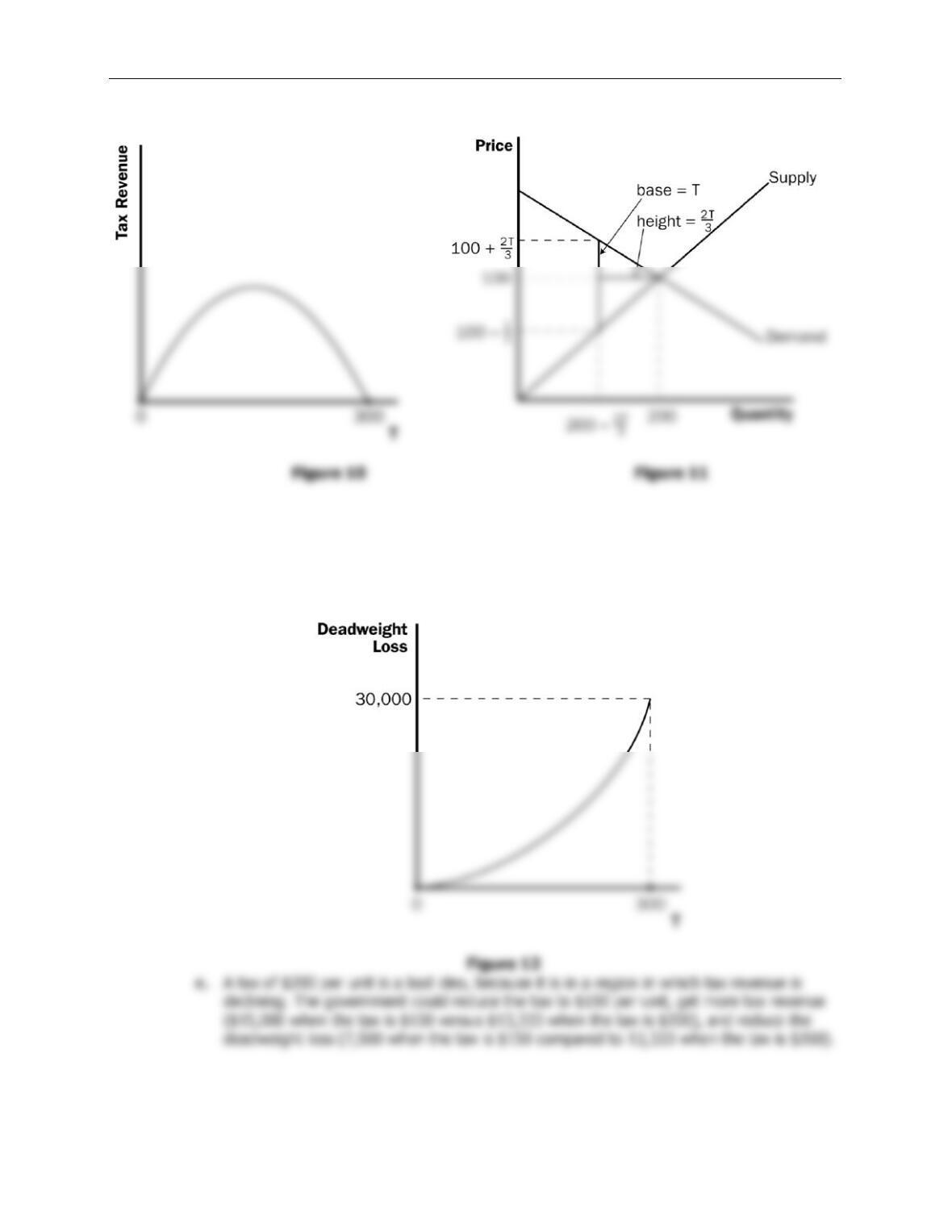

6. a. This tax has such a high rate that it is not likely to raise much revenue. Because of the

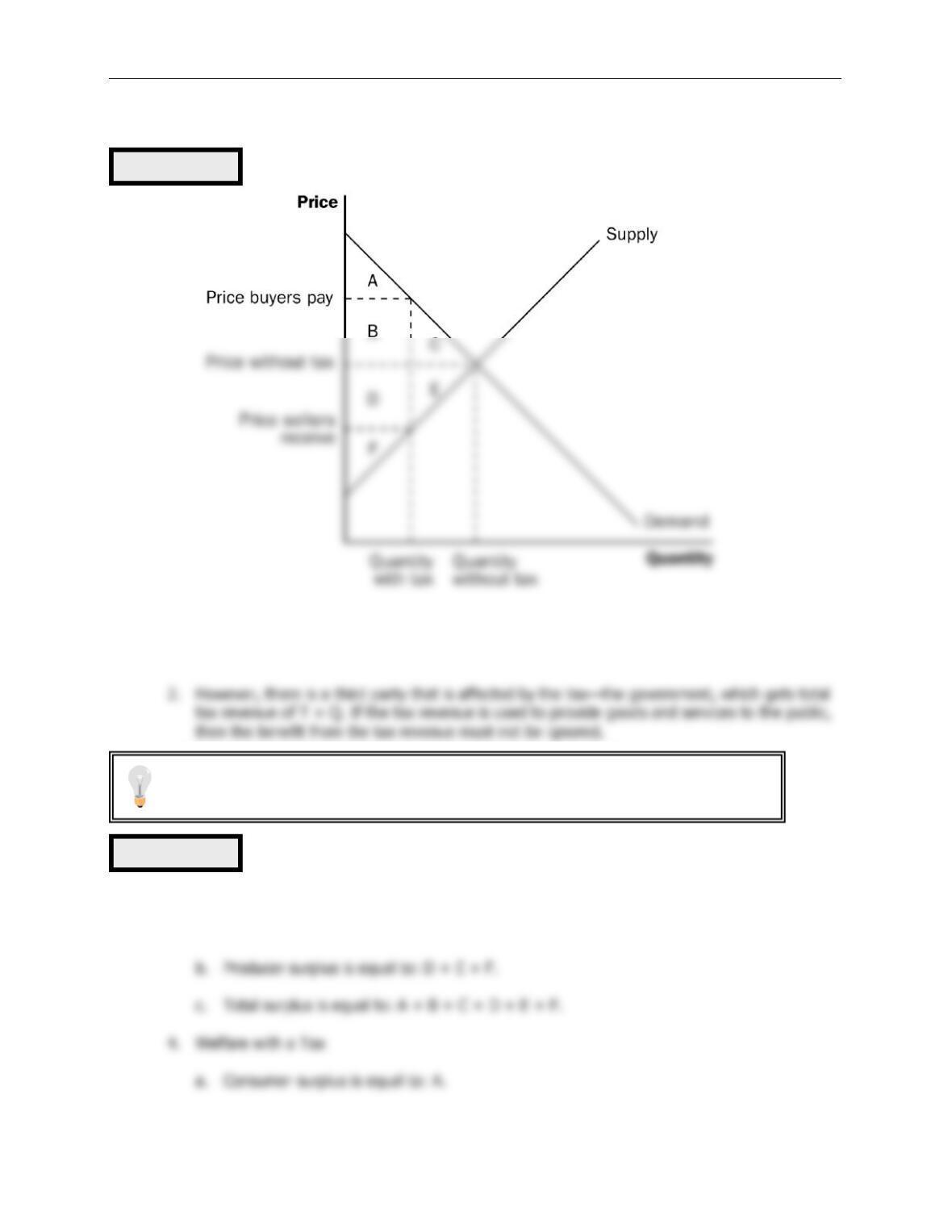

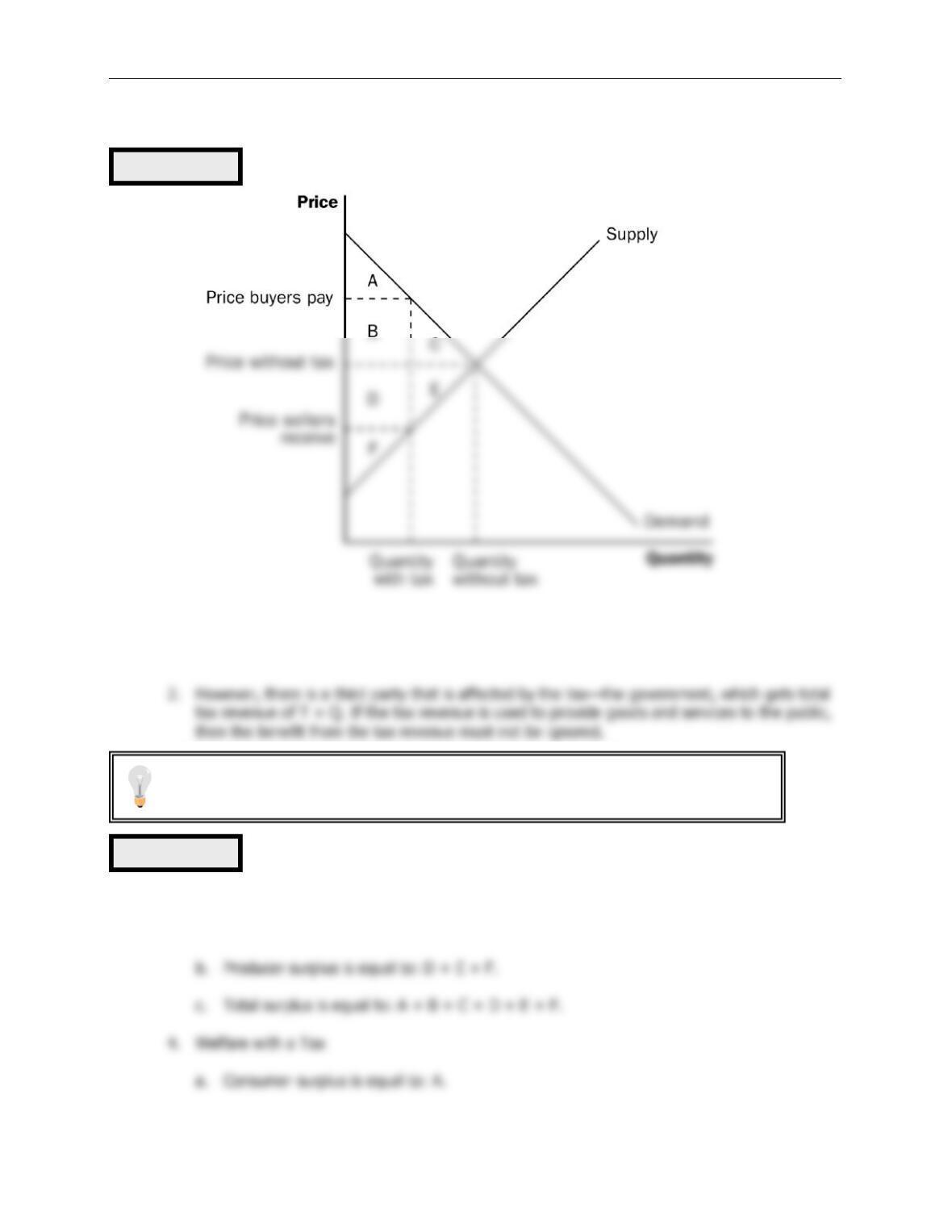

7. a. Figure 6 illustrates the market for socks and the effects of the tax. Without a tax, the

equilibrium quantity would be

Q

1, the equilibrium price would be

P

1, total spending by

consumers equals total revenue for producers, which is

P

1 x

Q

1, which equals area B + C

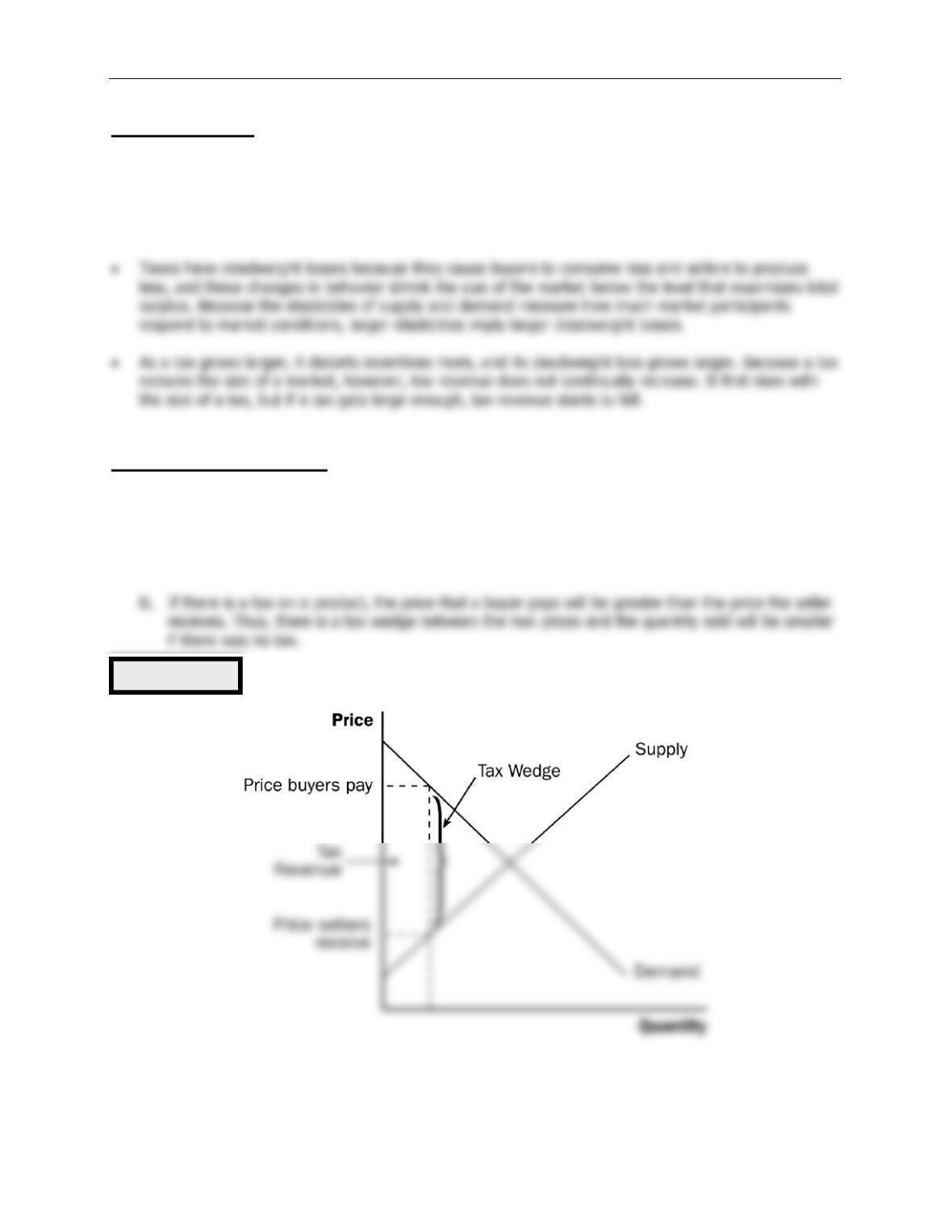

+ D + E + F, and government revenue is zero. The imposition of a tax places a wedge

between the price buyers pay,

P

B, and the price sellers receive,

P

S, where

P

B =

P

S + tax.

The quantity sold declines to

Q

2. Now total spending by consumers is

P

B x

Q

2, which

equals area A + B + C + D, total revenue for producers is

P

S x

Q

2, which is area C + D,

and government tax revenue is

Q

2 x tax, which is area A + B.

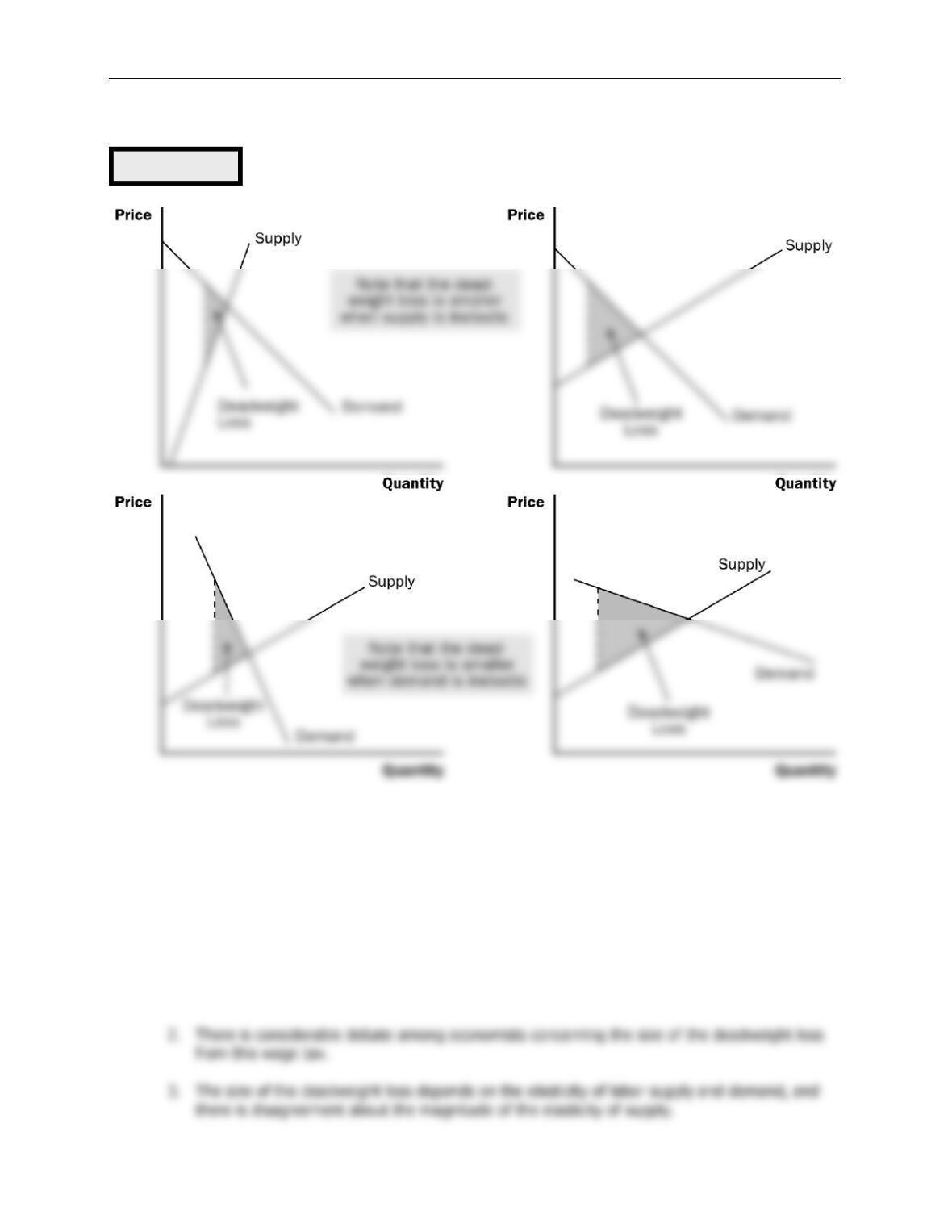

c. The price paid by consumers rises, unless demand is perfectly elastic or supply is

perfectly inelastic. Whether total spending by consumers rises or falls depends on the

price elasticity of demand. If demand is elastic, the percentage decline in quantity