Chapter 21/The Theory of Consumer Choice ❖ 375

2. We can show Sally's budget constraint graphically.

a. On the horizontal axis, we have hours of leisure. On the vertical axis, we have

consumption goods.

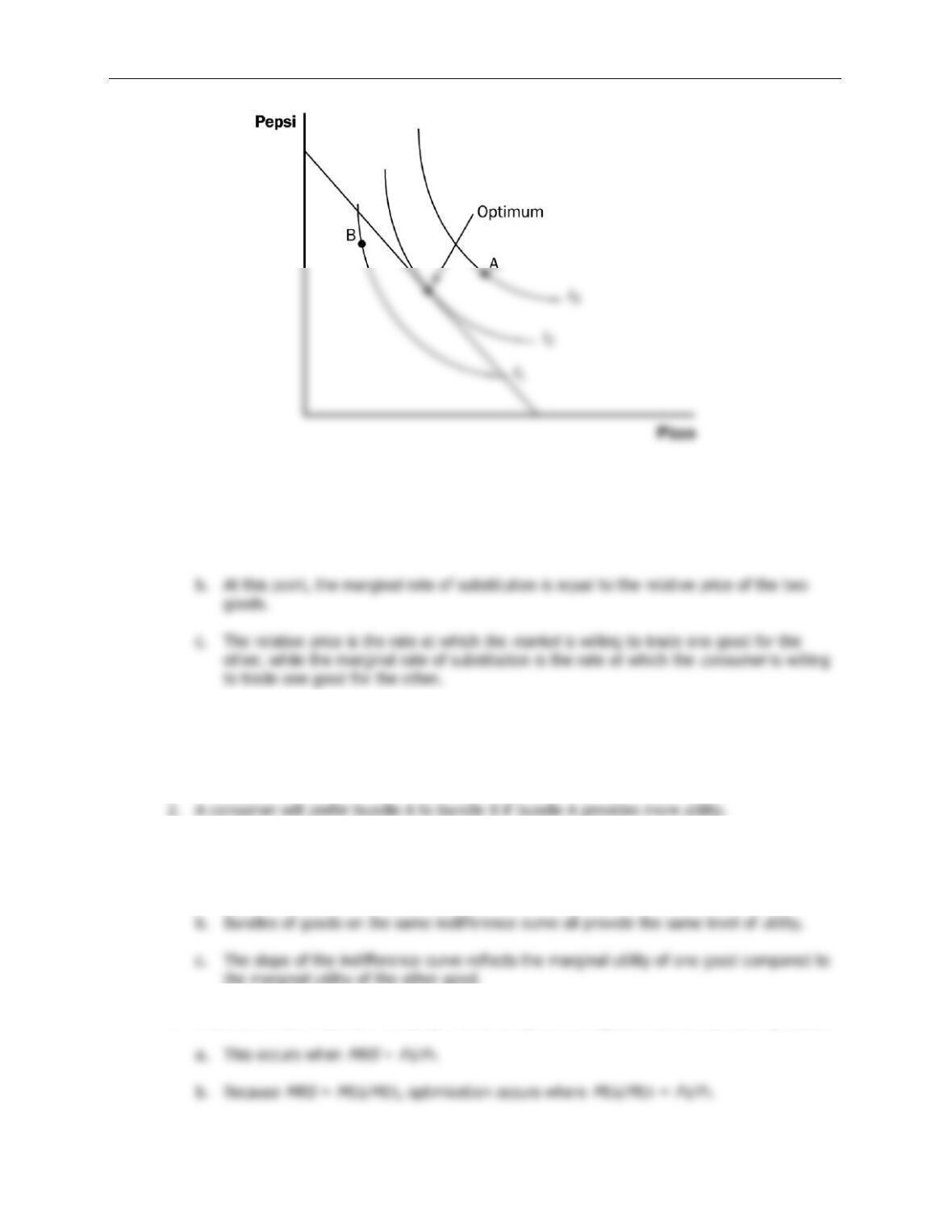

3. Sally's optimum will occur where the highest possible indifference curve is tangent to the

budget constraint.

4. If Sally's wage increases, her budget constraint will shift outward.

a. The budget constraint will become steeper, because Sally can get more consumption for

every hour of leisure that she gives up.

d. If the substitution effect is greater than the income effect, Sally will decrease leisure and

work more hours if her wage rises. This results in an upward-sloping labor supply curve.

5.

Case Study: Income Effects on Labor Supply: Historical Trends, Lottery Winners, and the

Carnegie Conjecture

a. One hundred years ago, workers worked six days a week. As wages (adjusted for

inflation) have risen, the length of the workweek has fallen. This suggests that a

backward-bending labor supply curve is not unrealistic.