Gannon and Pillai, Understanding Global Cultures, Sixth Edition Instructor Resource

CHAPTER 1: UNDERSTANDING CROSS-CULTURAL DIFFERENCES

EXERCISE 1.1: CULTURE AND GROUP EFFECTIVENESS

Many individuals do not consider that cultural differences or culture are important. They

believe that individuals tend to be similar across cultures. This opening exercise and other ones

in the early chapters address the importance of culture.

Using think-pair-share, the instructor should ask students why there is a disparity

between the group effectiveness of cross-cultural and single culture groups within organizations,

and what are the major strengths and weaknesses of these two different types of groups. The

think-pair-share method involves three stages: (1) students think silently for one minute;

(2) each student then discusses his or her thoughts with the student sitting next to him or her; and

(3) there is a class discussion.

Comments: Just as there are cultural paradoxes, so too there is the paradox of multi-cultural

team effectiveness. That is, while multi-cultural teams have the potential to be the most effective

and productive teams in organizations, they also can be the least productive. But teams

comprised of all members from a single culture tend to be of average effectiveness.

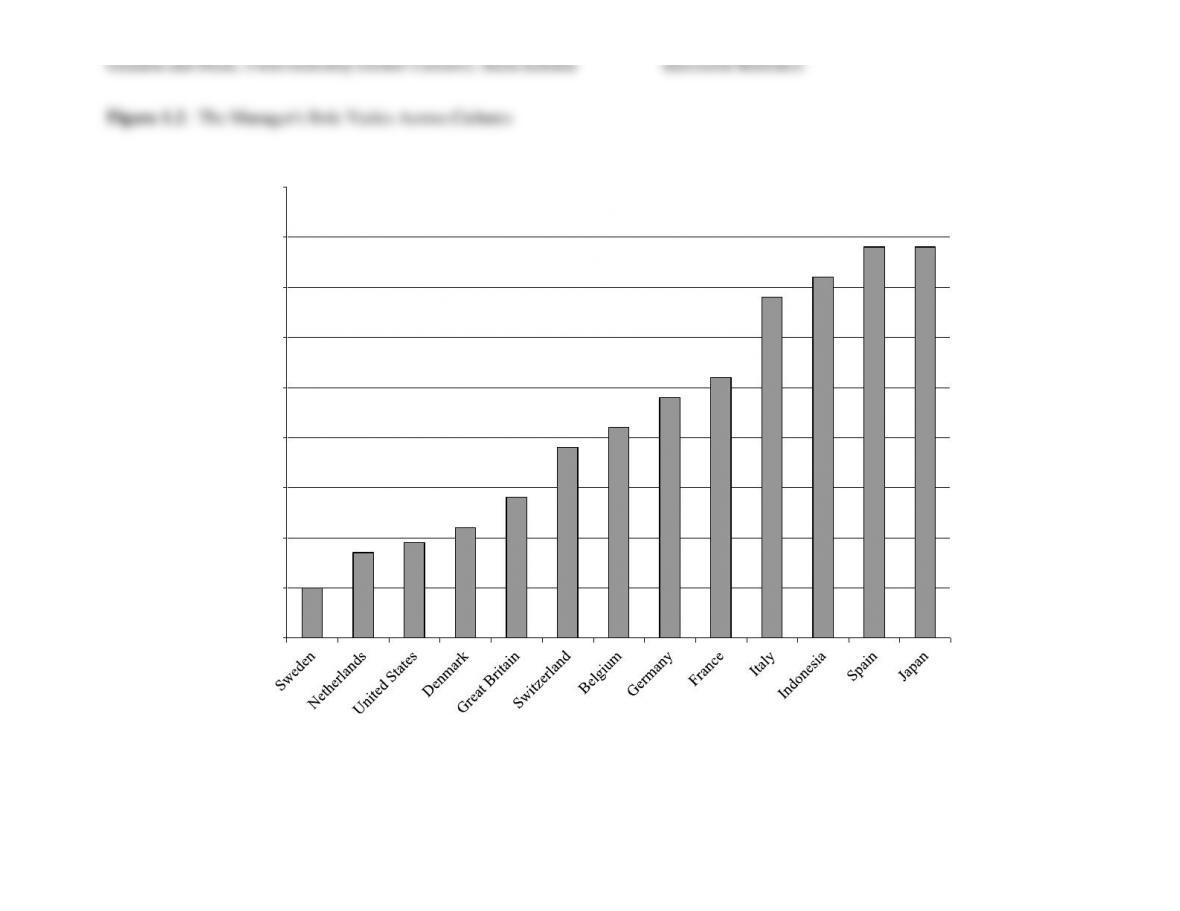

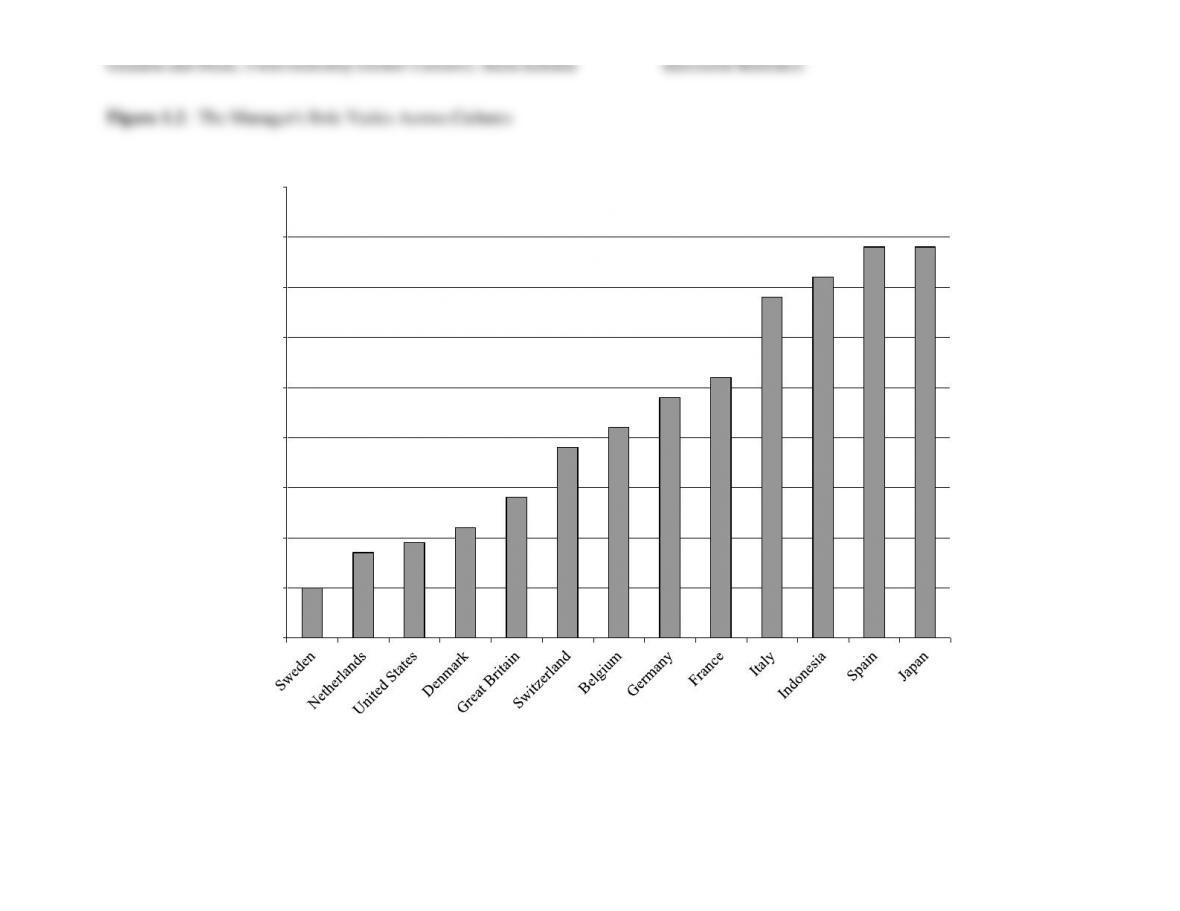

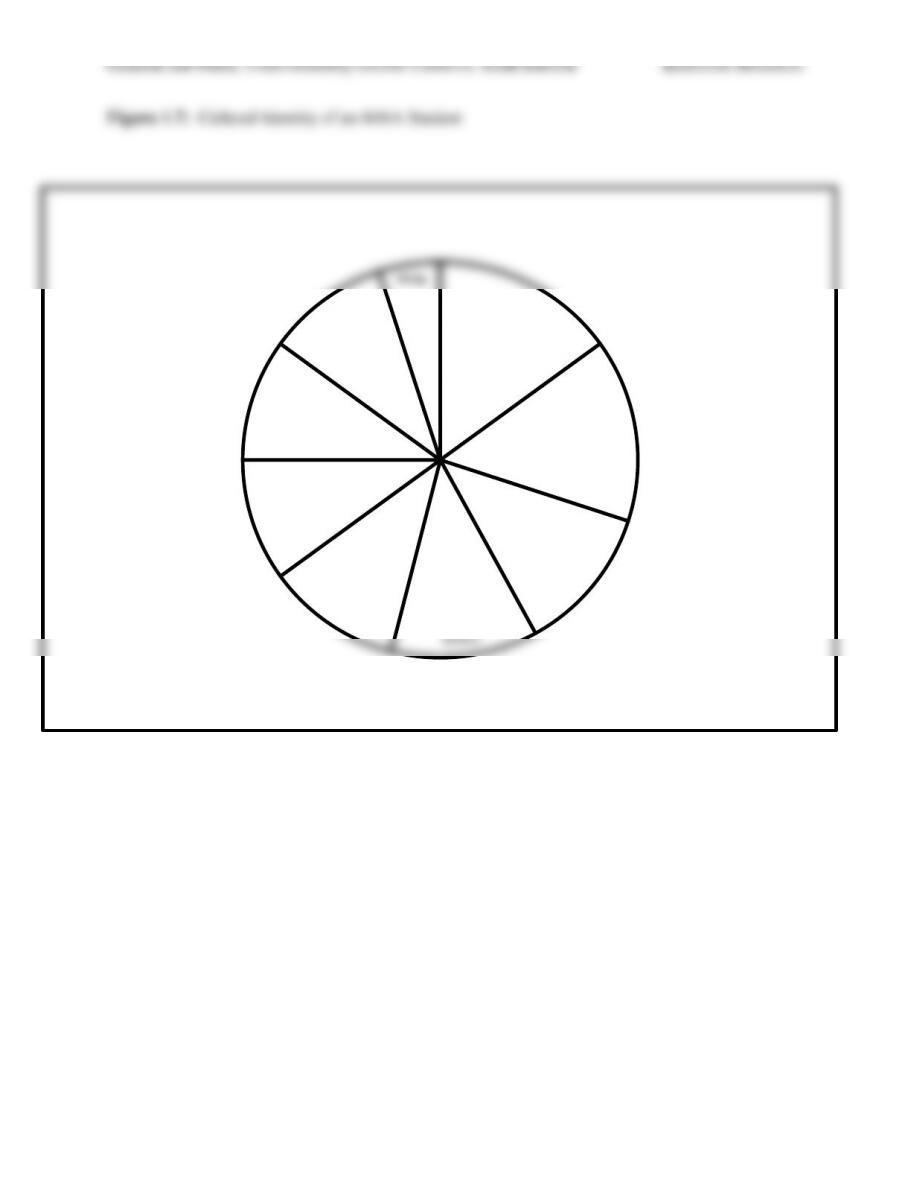

Figure 1.1 shows the relative productivity of a series of 800 four to six member teams as

observed by Dr. Carol Kovach at UCLA (see Adler, 1997). This figure provides some important

insights. First, it is clear that there is a wide disparity in the effectiveness of multi-cultural

teams, which suggests that certain factors in cross-cultural interactions and communication must

exist which can either facilitate or hinder the effectiveness of such teams. The figure also leads

us to believe that diversity among team members is one quality that at least has the potential to

increase effectiveness, as single-culture teams are limited in their ability to achieve high

effectiveness.

The instructor may also want to point out that any minority-group members in a team or

group primarily composed of one type – e.g., a male in an all-female group – are treated as a

"token" and not assumed to be any different in terms of values and behaviors until minority

representation reaches 20% (see Cox, 1993). At or above that point the group members realize

that they no longer constitute a single culture group. The group then tends to follow the

traditional model of group dynamics, that is: