156 ❖ Chapter 8 /Application: The Costs of Taxation

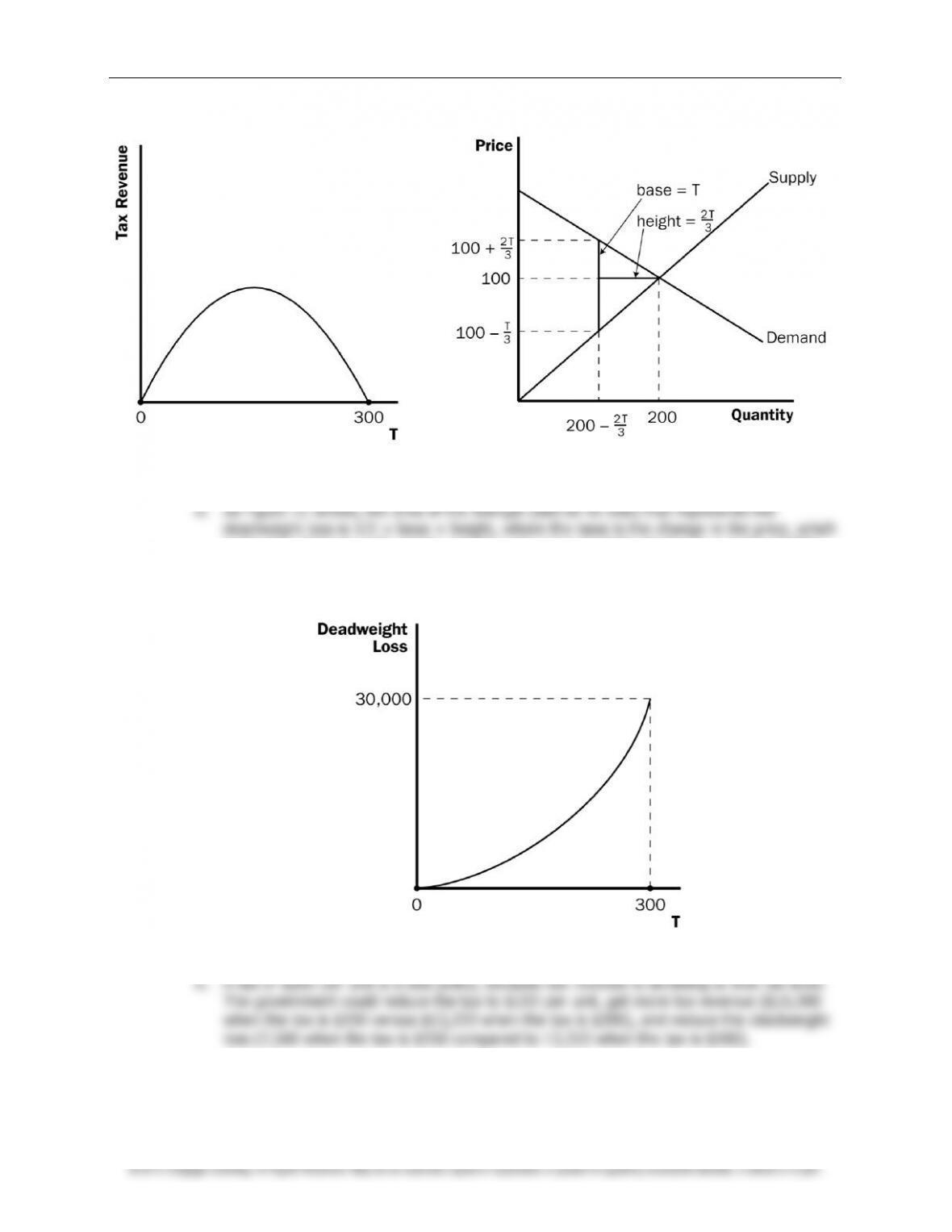

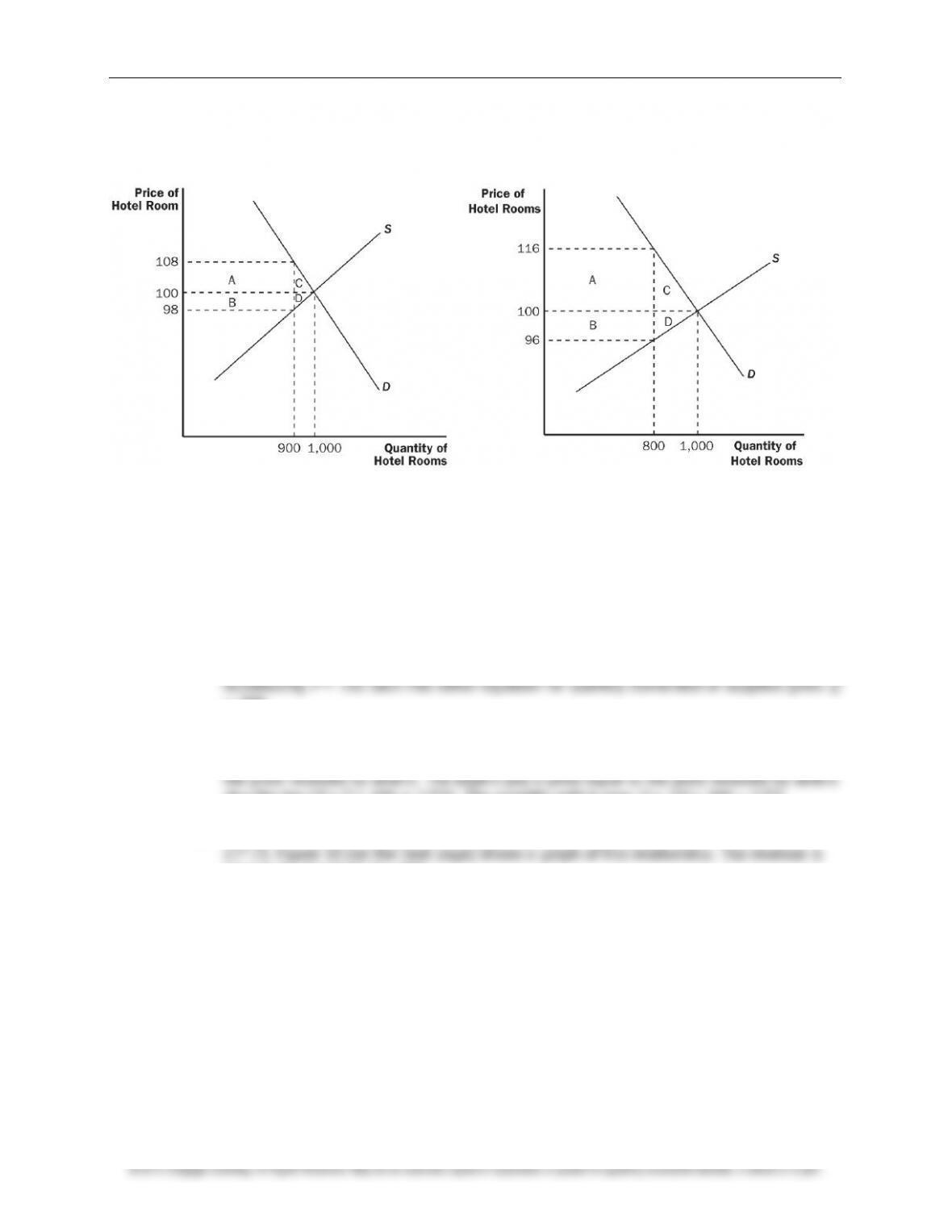

b. The tax revenue is likely to be higher in the first year after it is imposed than in the fifth

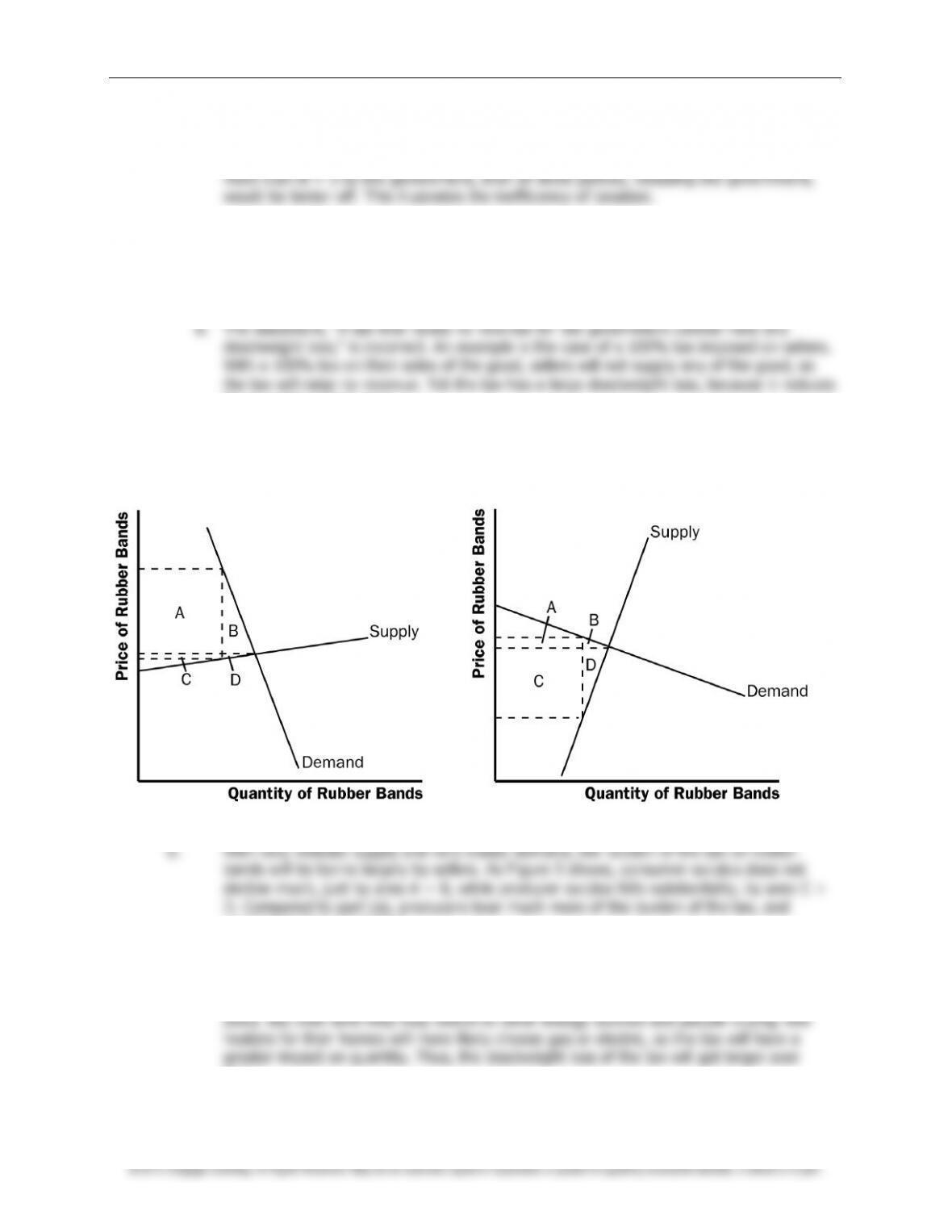

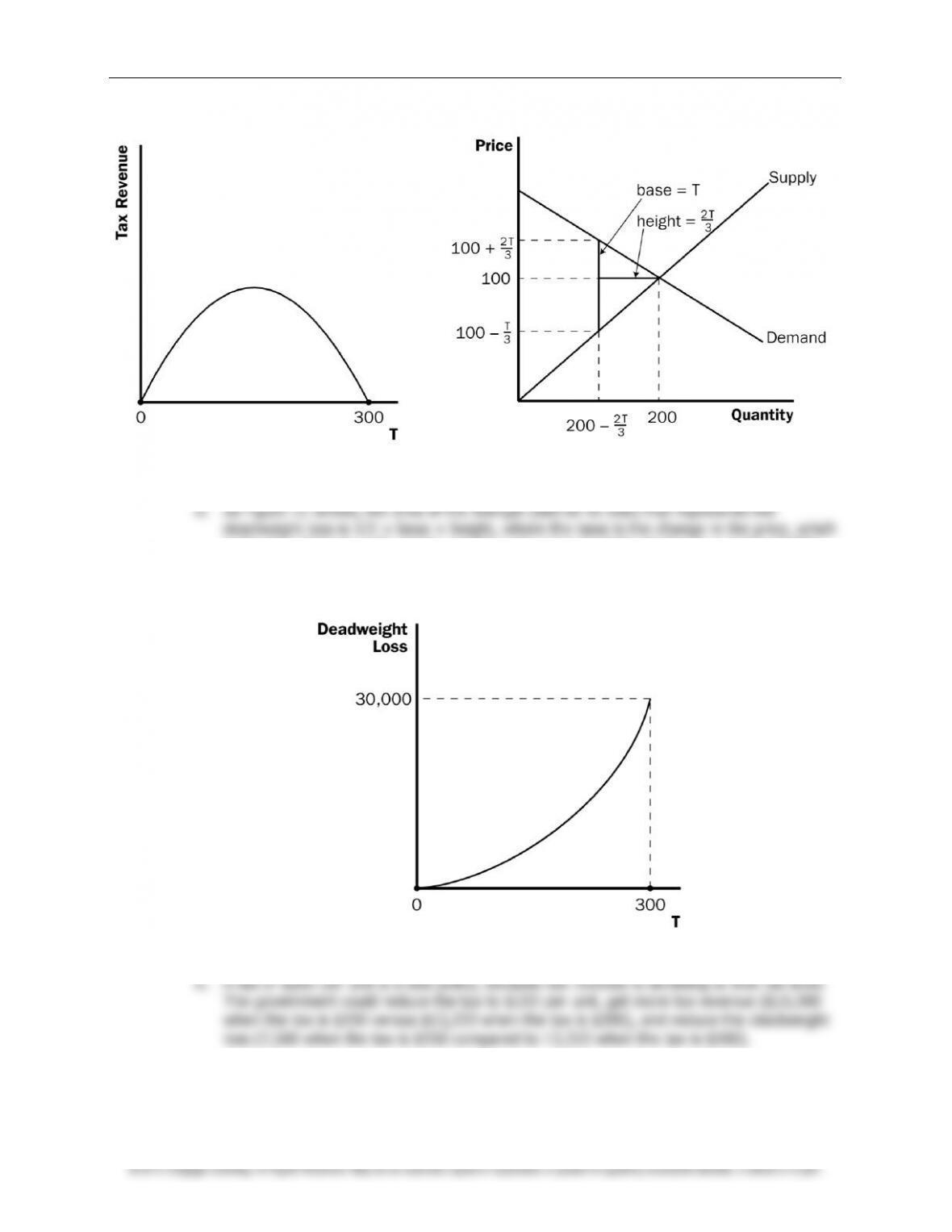

5. Because the demand for food is inelastic, a tax on food is a good way to raise revenue

because it leads to a small deadweight loss; thus taxing food is less inefficient than taxing

other things. But it is not a good way to raise revenue from an equity point of view, because

poorer people spend a higher proportion of their income on food. The tax would affect them

more than it would affect wealthier people.

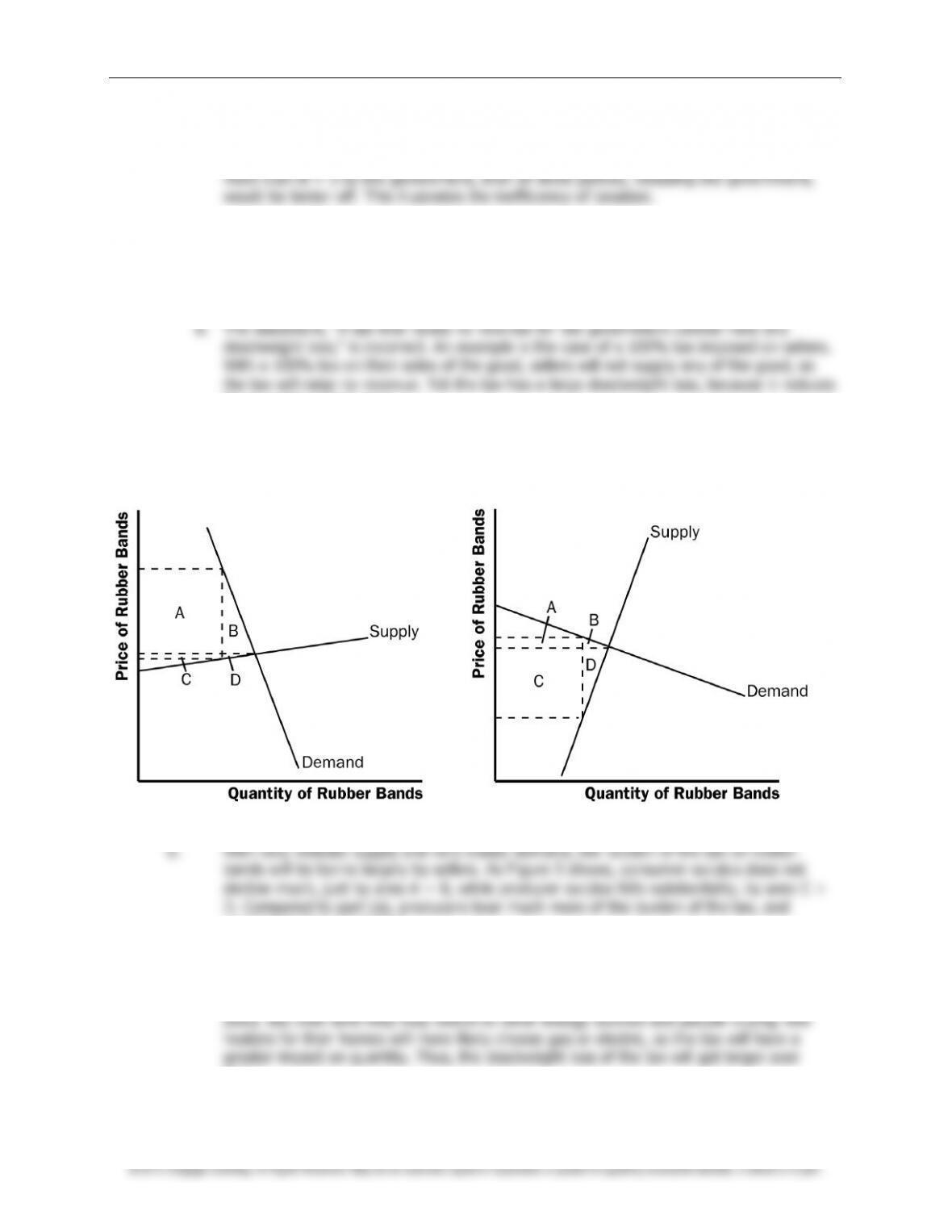

b. Senator Moynihan's goal was probably to ban the use of hollow-tipped bullets. In this

case, the tax could be as effective as an outright ban.

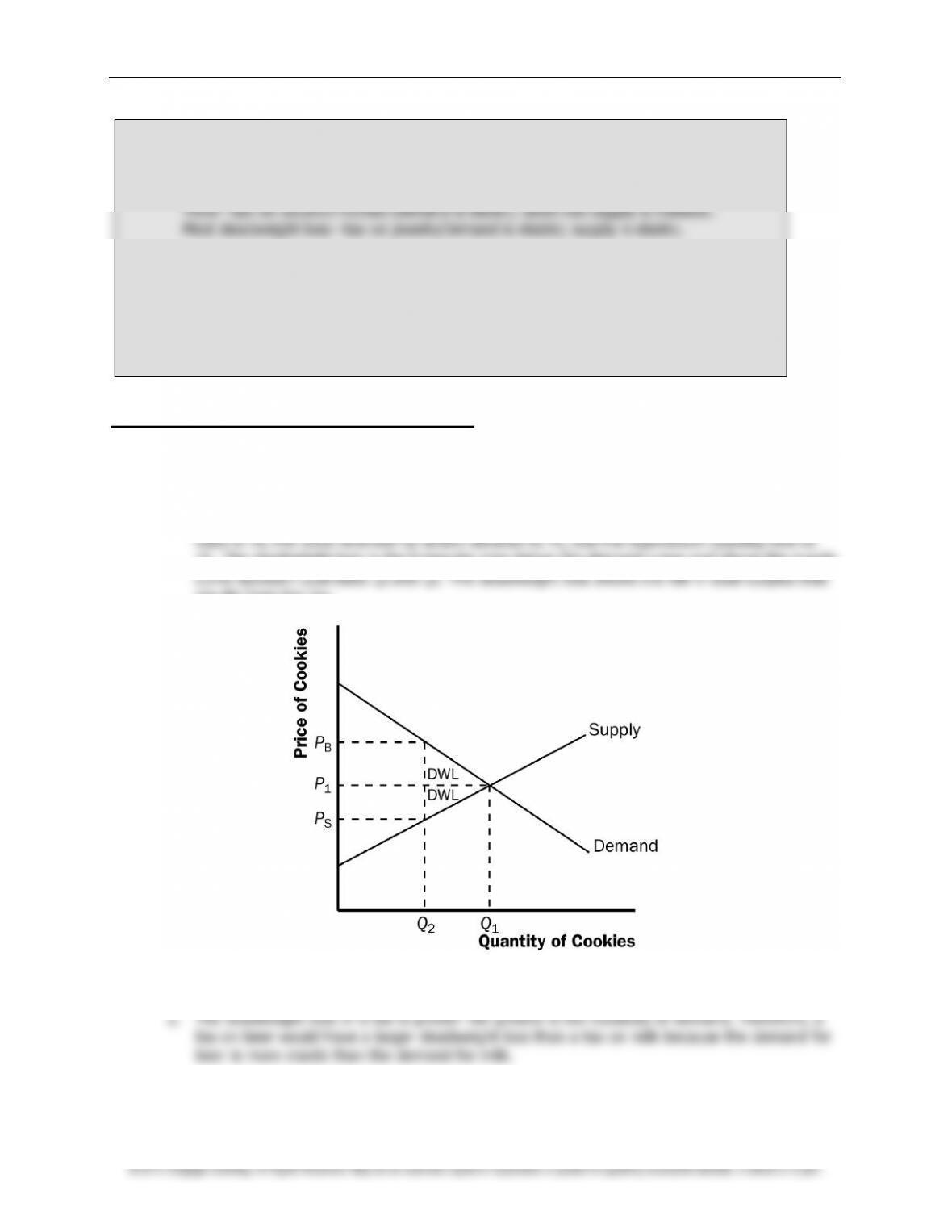

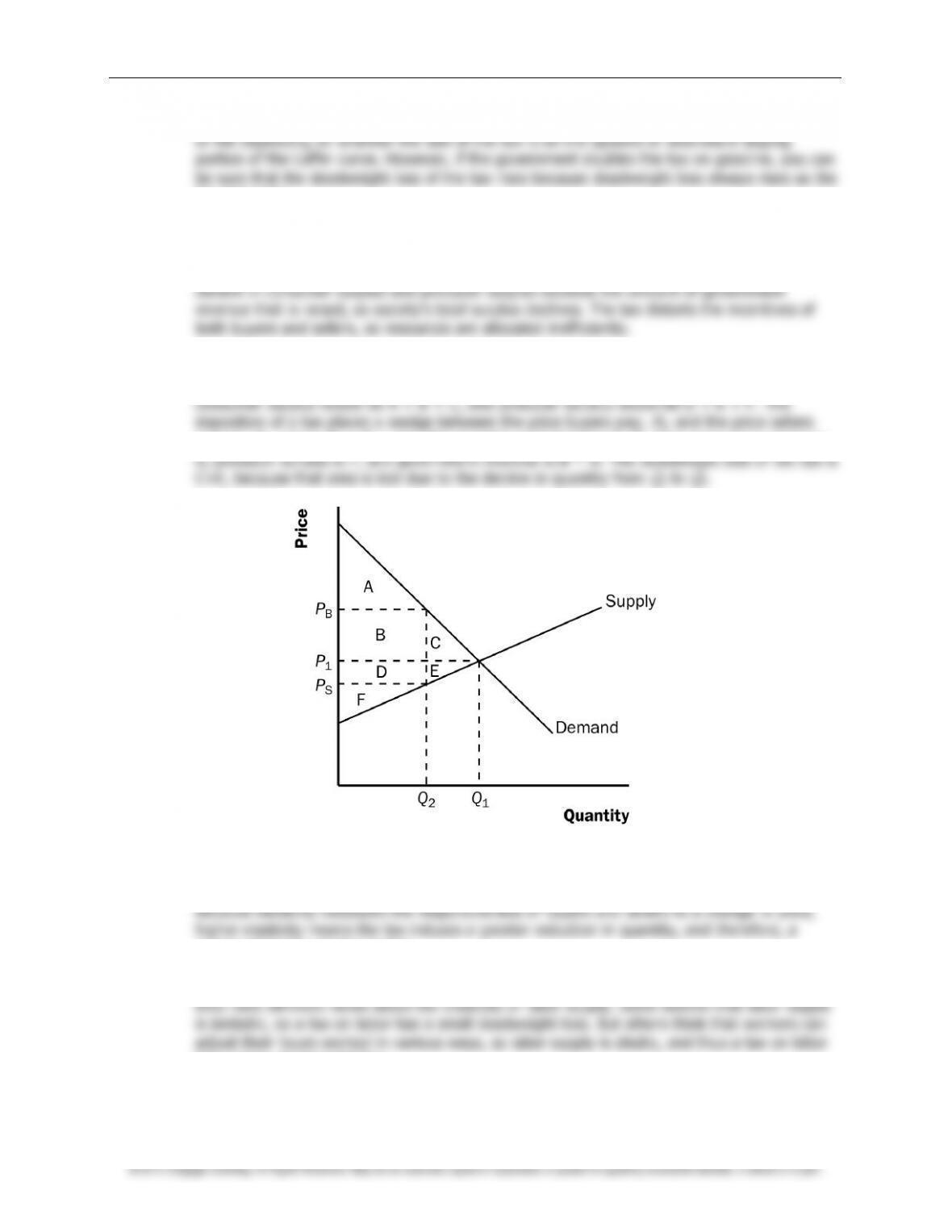

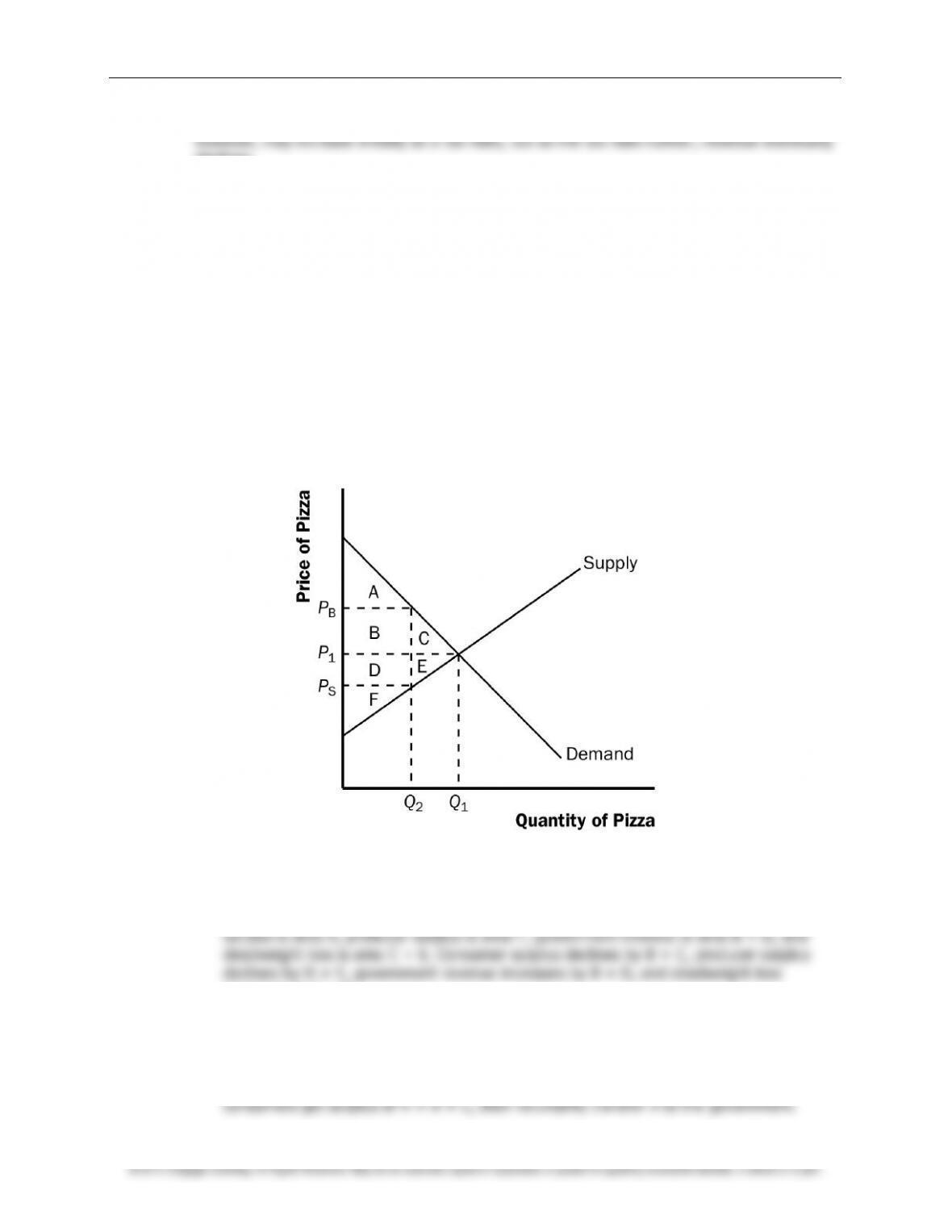

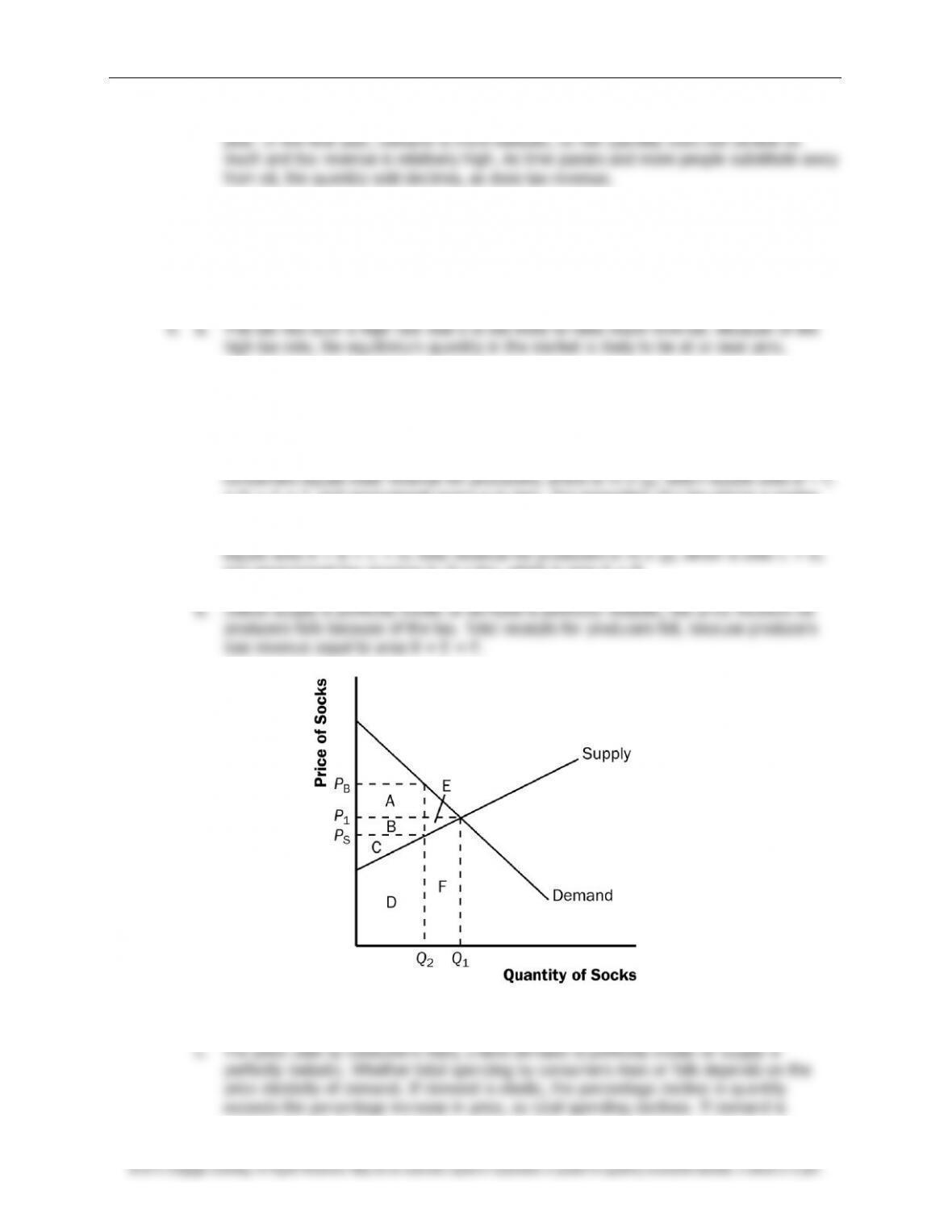

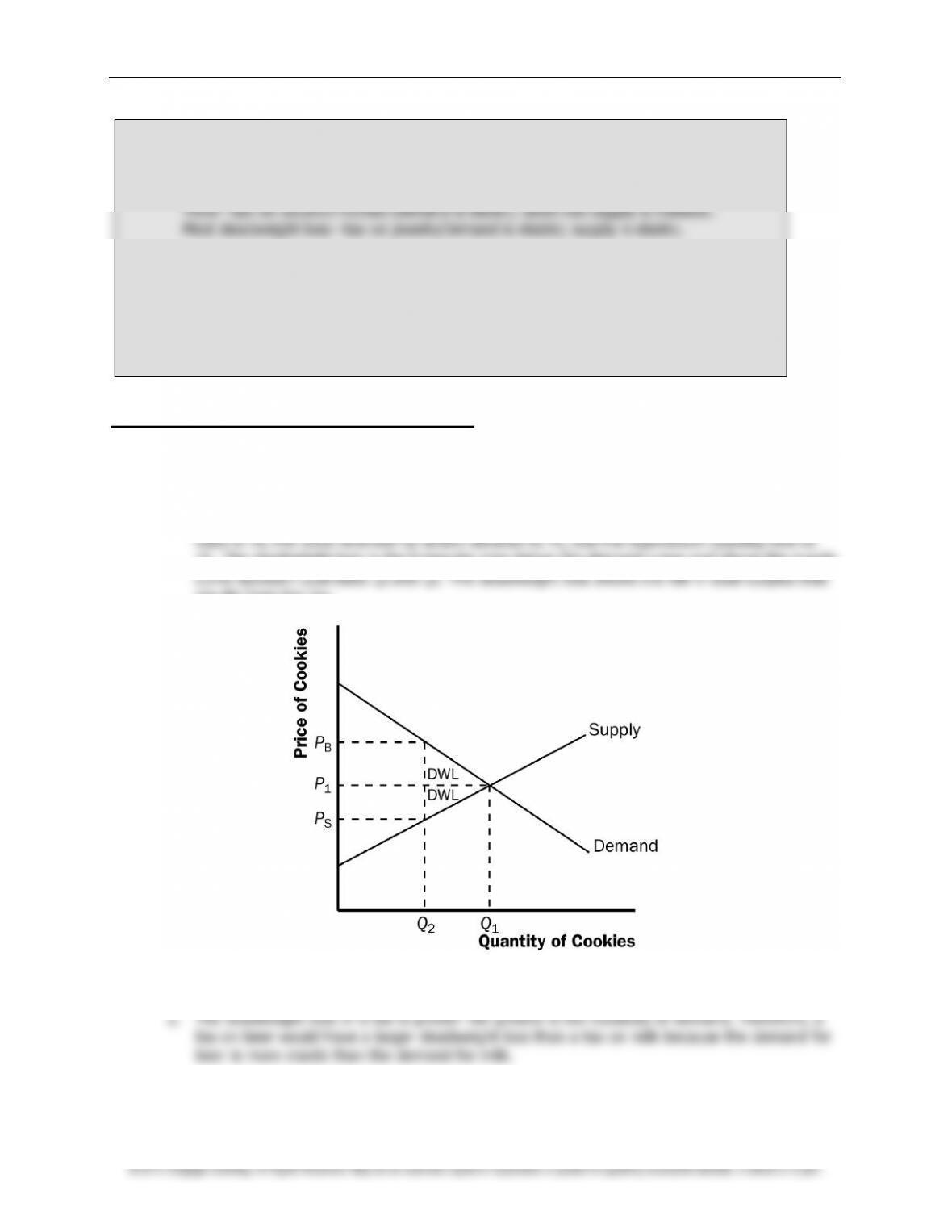

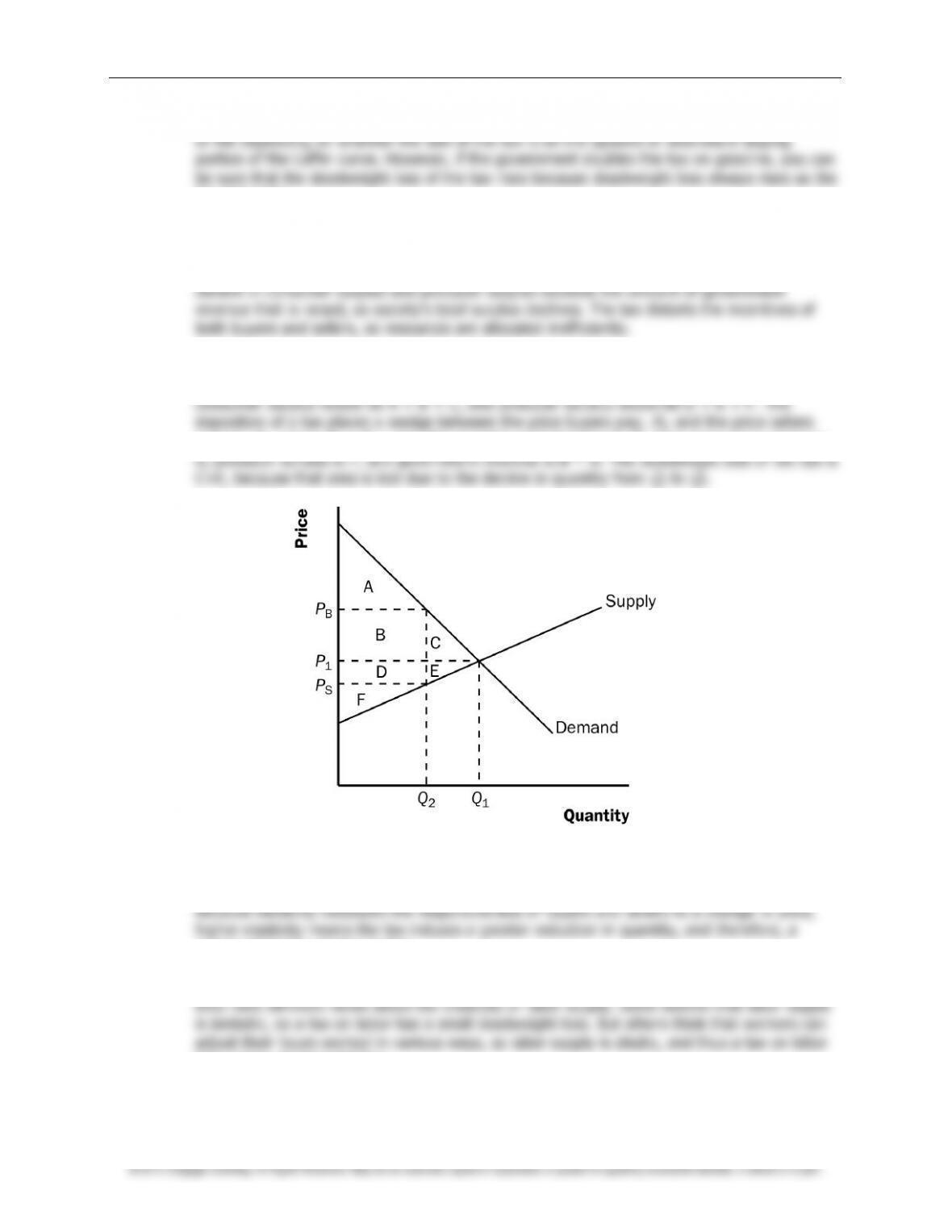

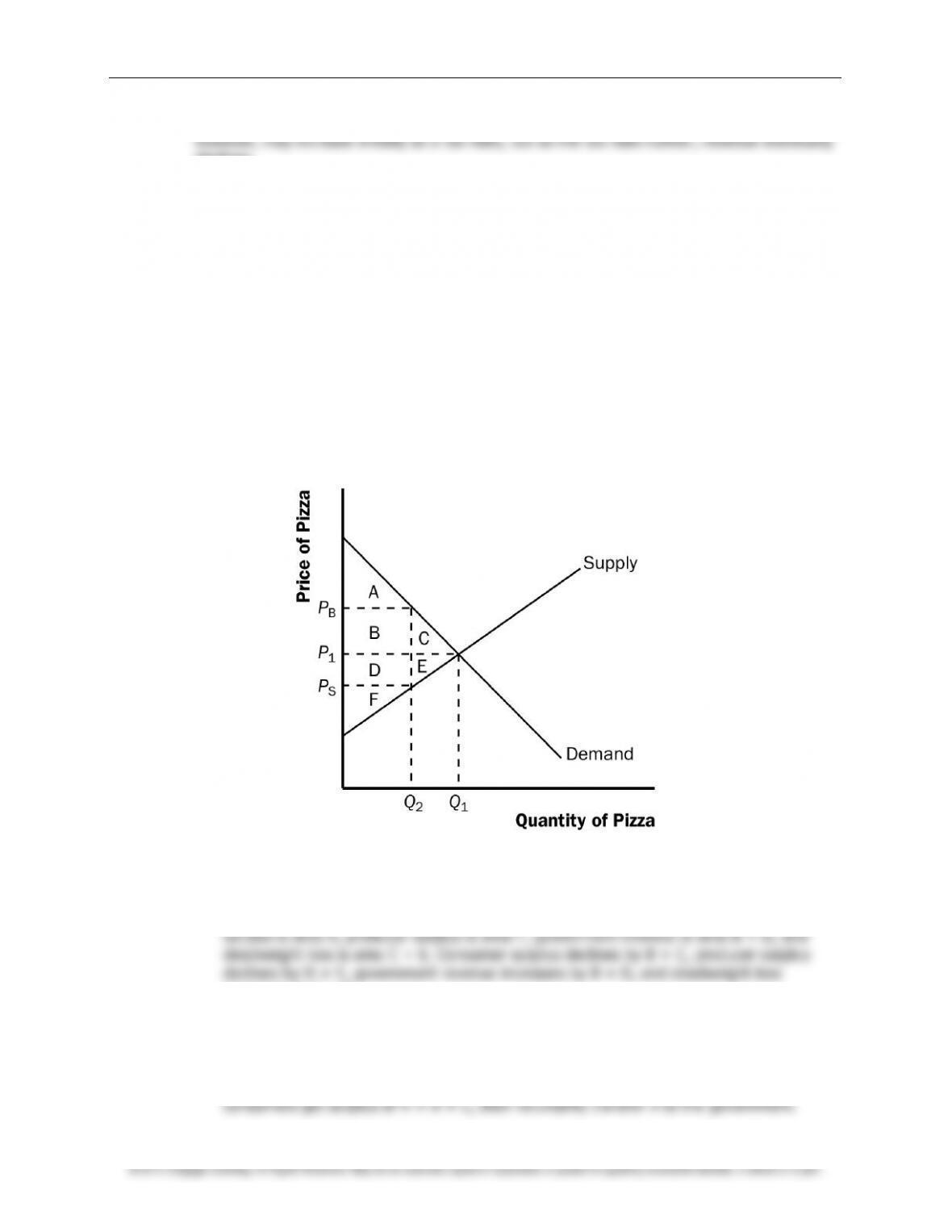

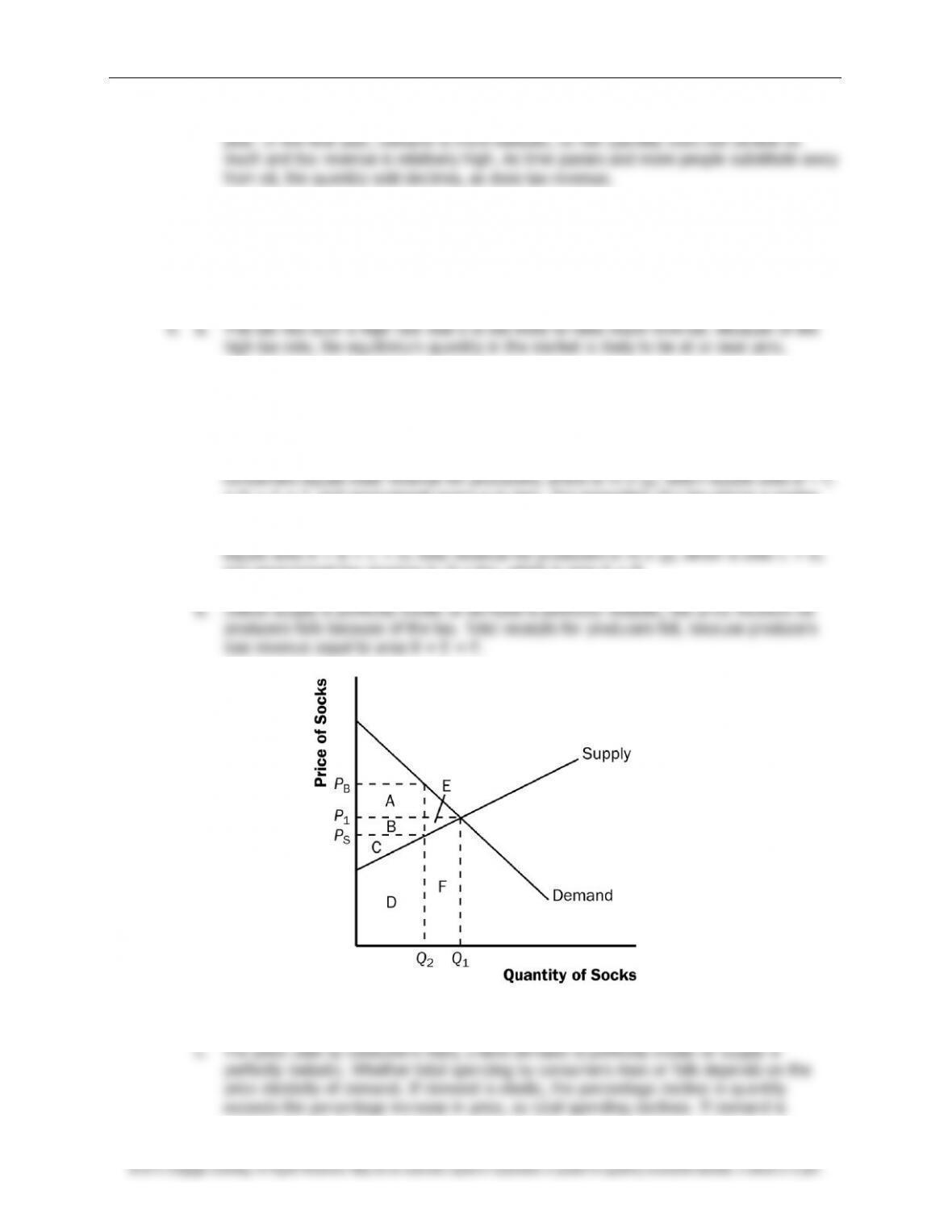

7. a. Figure 6 illustrates the market for socks and the effects of the tax. Without a tax, the

equilibrium quantity would be

Q

1, the equilibrium price would be

P

1, total spending by

+ D + E + F, and government revenue is zero. The imposition of a tax places a wedge

between the price buyers pay,

P

B, and the price sellers receive,

P

S, where

P

B =

P

S + tax.

The quantity sold declines to

Q

2. Now total spending by consumers is

P

B x

Q

2, which

and government tax revenue is

Q

2 x tax, which is area A + B.

Figure 6