370 ❖ Chapter 21/The Theory of Consumer Choice

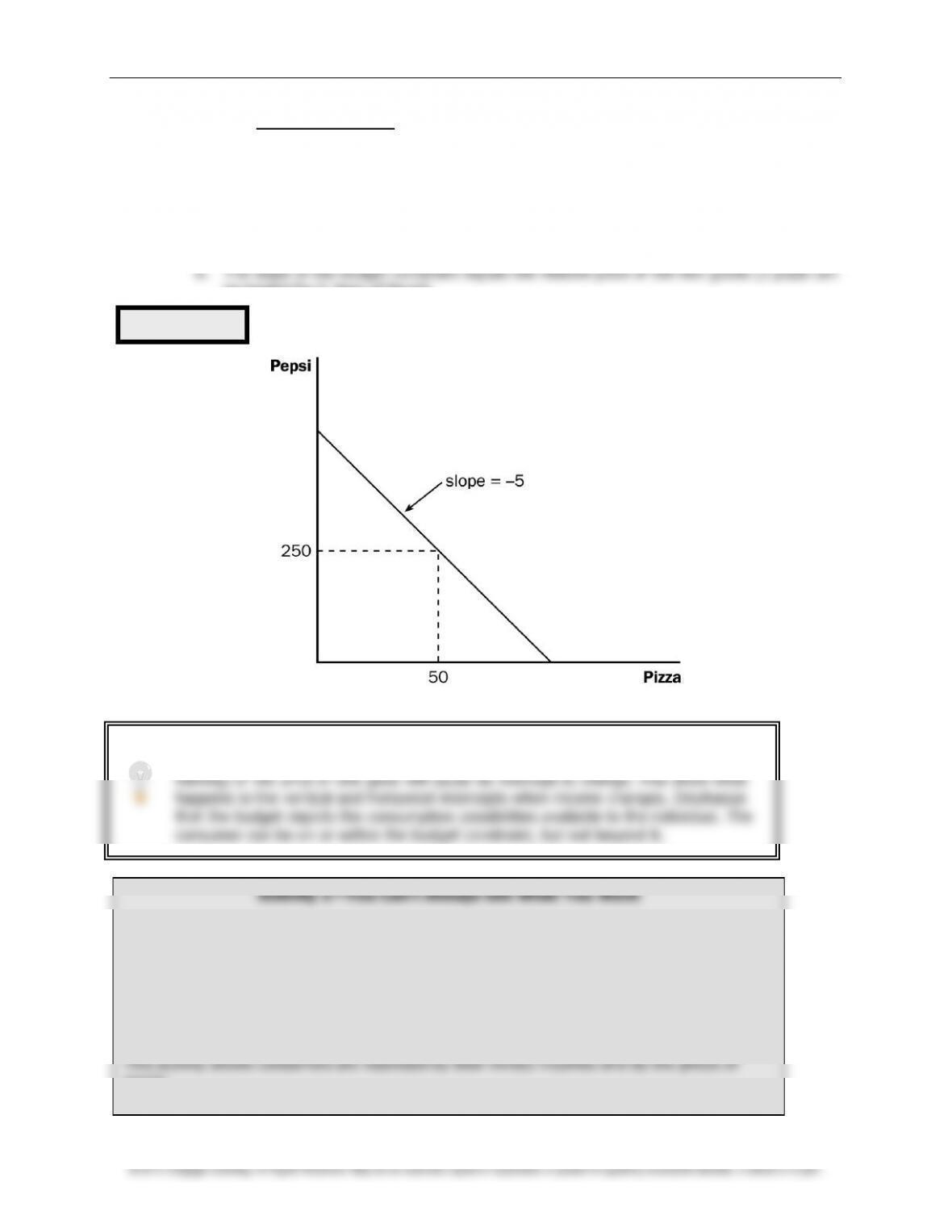

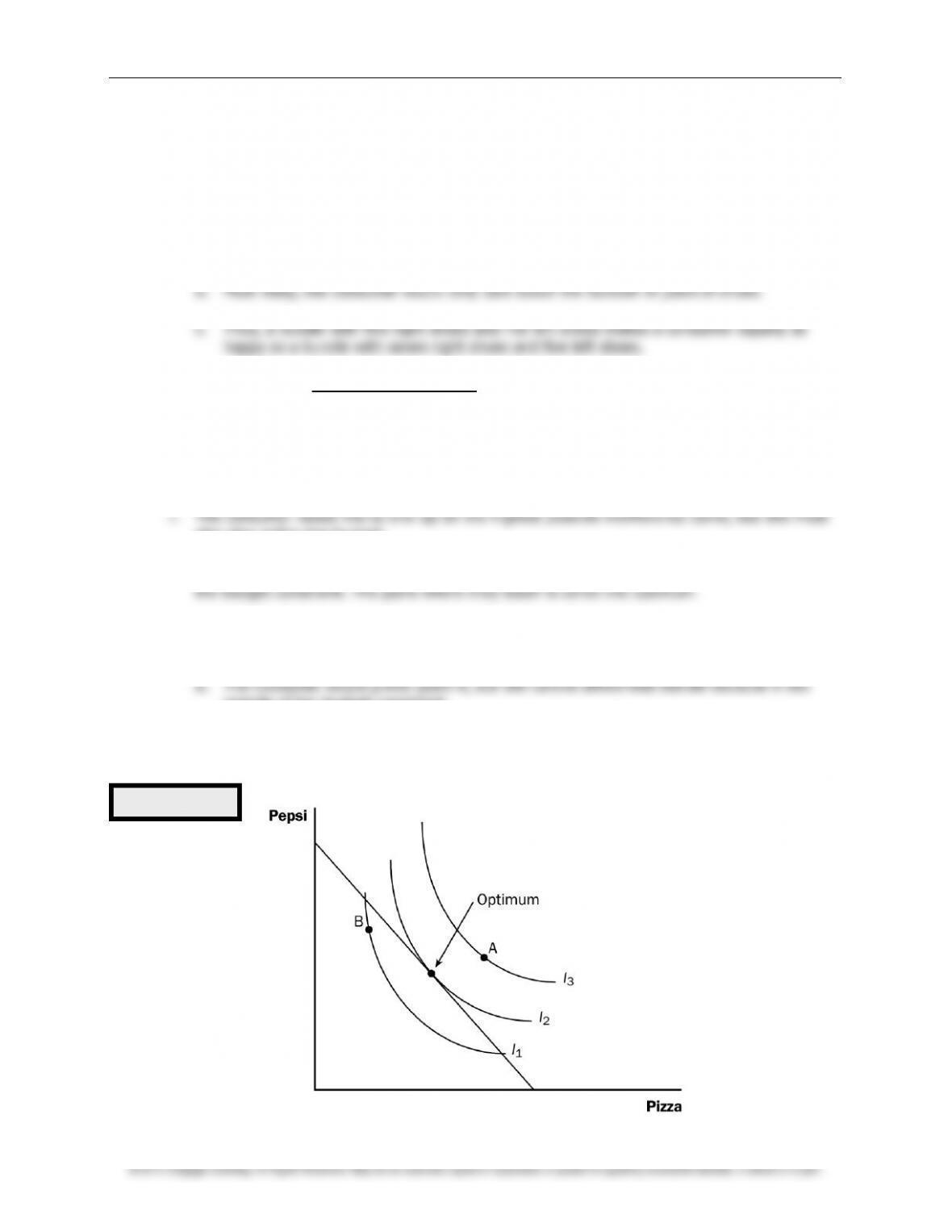

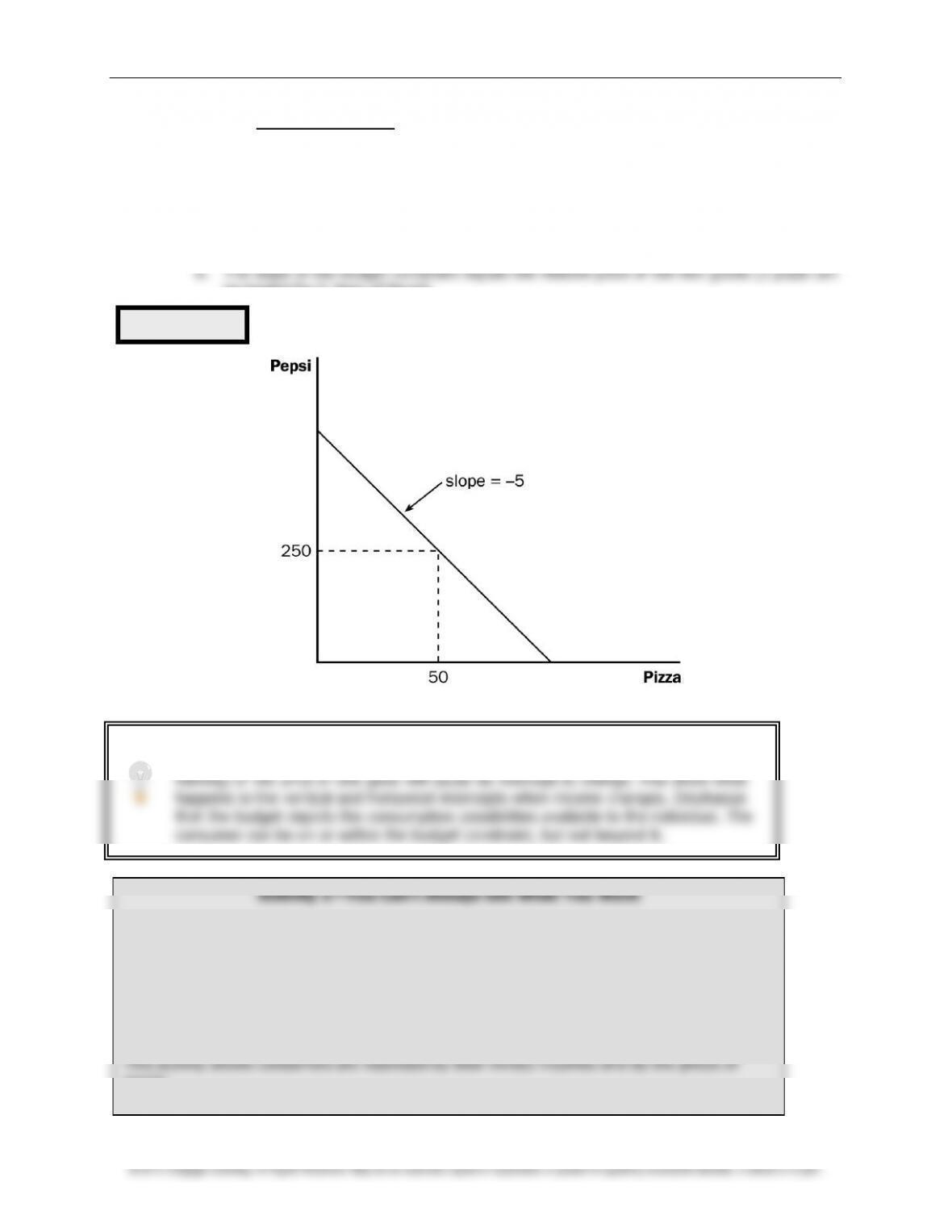

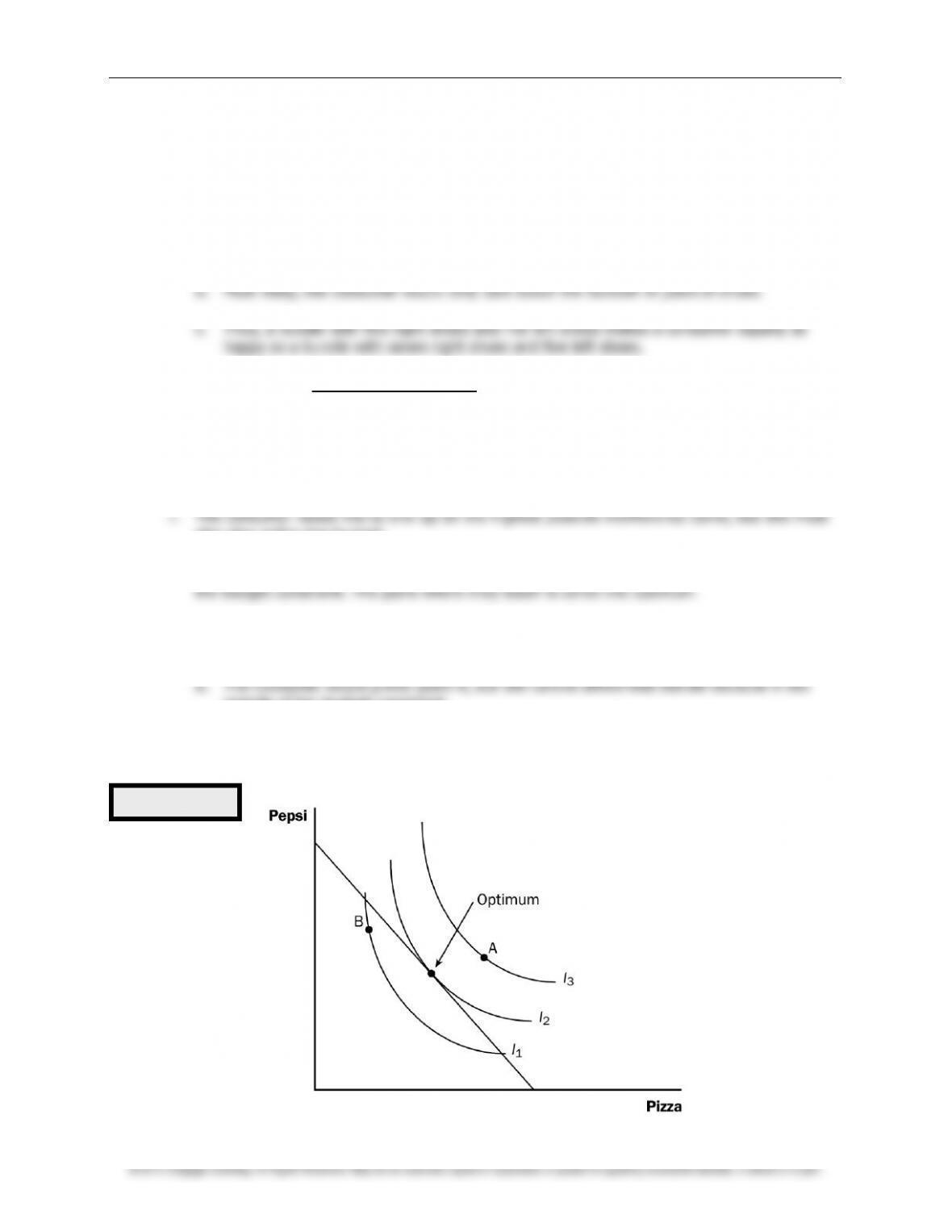

4. At the optimum, the slope of the budget constraint is equal to the slope of the indifference

curve.

a. The indifference curve is tangent to the budget constraint at this point.

b. At this point, the marginal rate of substitution is equal to the relative price of the two

goods.

c. The relative price is the rate at which the

market

is willing to trade one good for the

other, while the marginal rate of substitution is the rate at which the

consumer

is willing

to trade one good for the other.

B.

FYI: Utility: An Alternative Way to Describe Preferences and Optimization

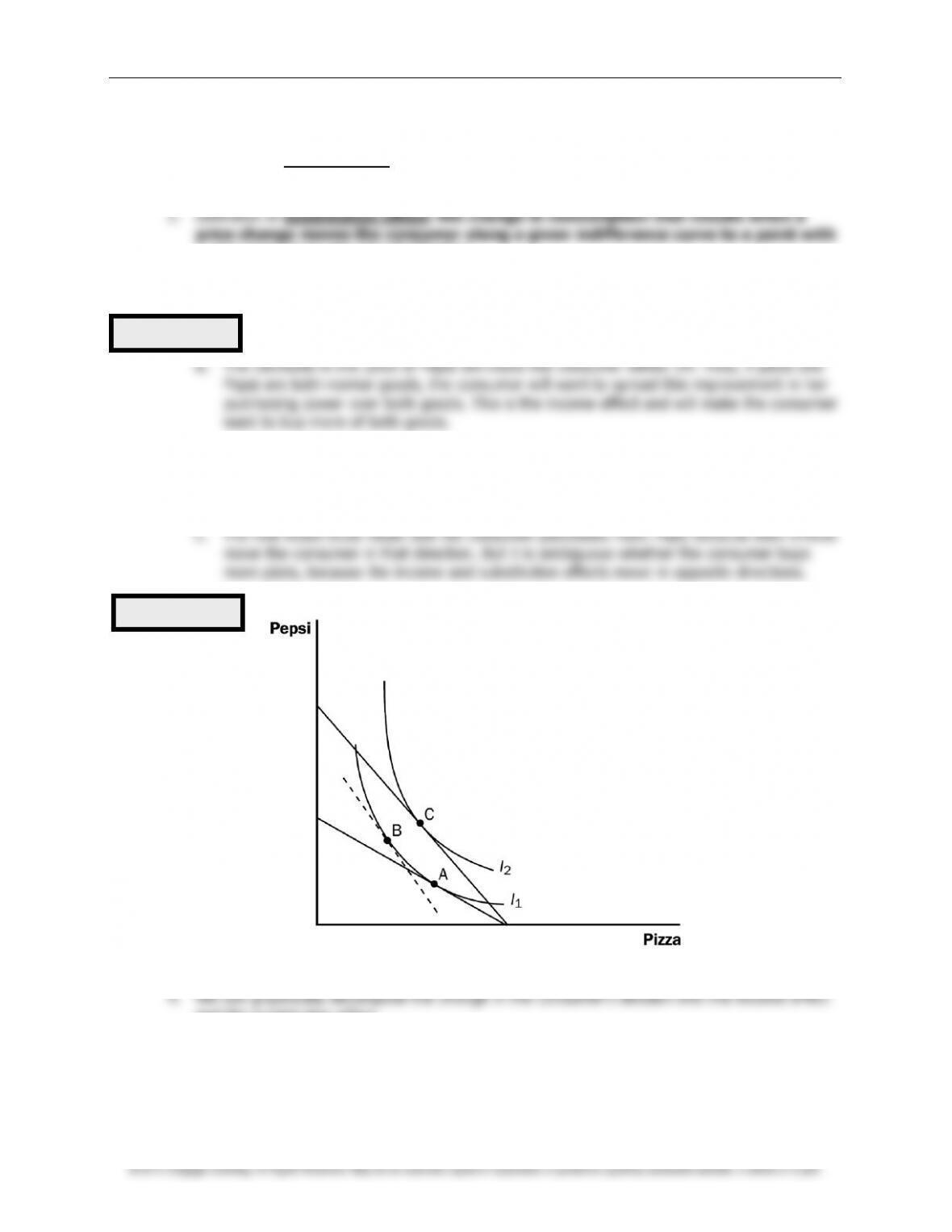

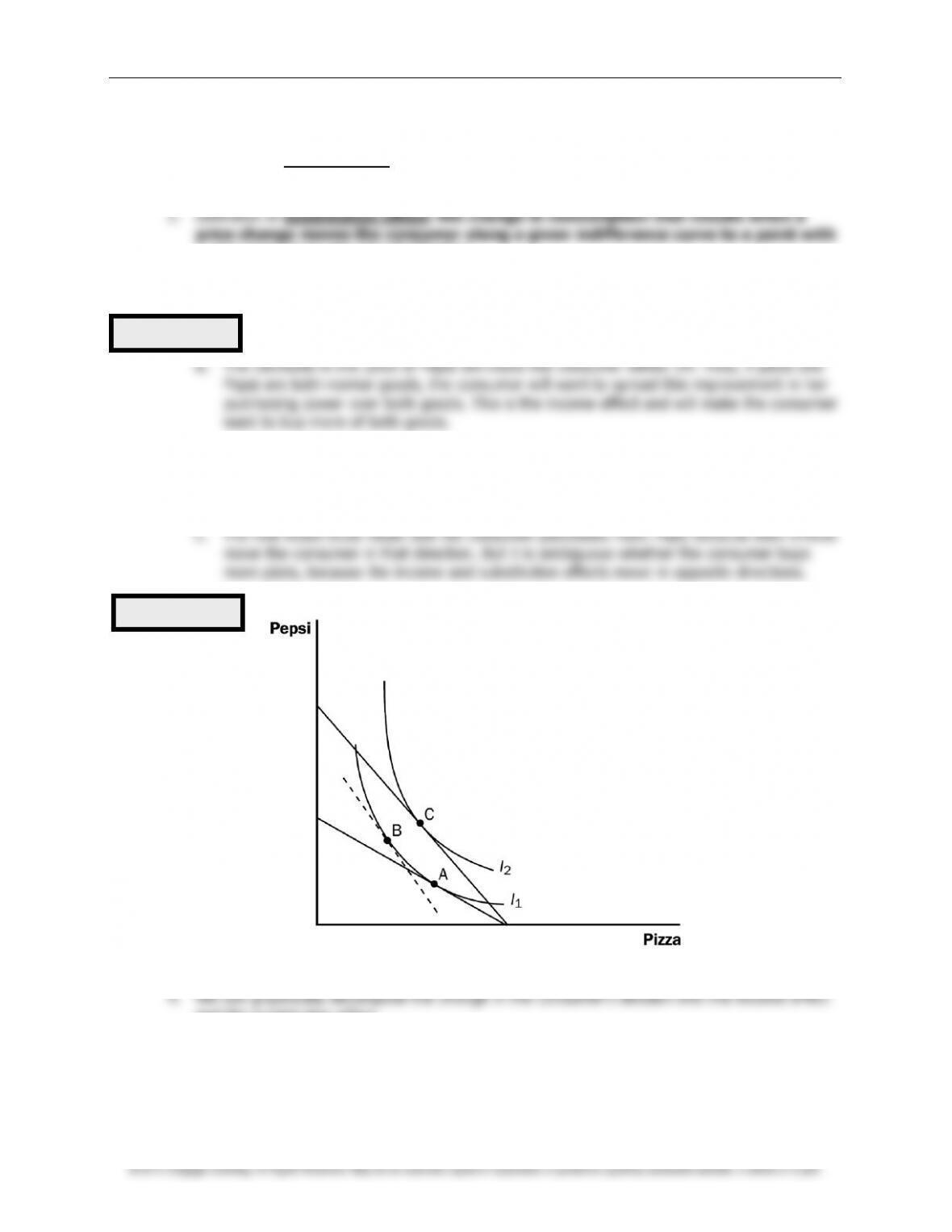

1. Utility is an abstract measure of the satisfaction that a consumer receives from a bundle of

goods and services.

2. A consumer will prefer bundle A to bundle B if bundle A provides more utility.

3. Indifference curves and utility are related.

a. Bundles of goods in higher indifference curves provide a higher level of utility.

b. Bundles of goods on the same indifference curve all provide the same level of utility.

c. The slope of the indifference curve reflects the marginal utility of one good compared to

the marginal utility of the other good.

4. A consumer can maximize her utility if she ends up on the highest indifference curve

possible.

a. This occurs when

MRS

=

PX

/

PY

.

b. Because

MRS

=

MUX

/

MUY

, optimization occurs where

MUX

/

MUY

=

PX

/

PY

.

c. This can be rewritten as

MUX

/

PX

=

MUY

/

PY

.

good

X

equals the marginal utility per dollar spent on good

Y

.

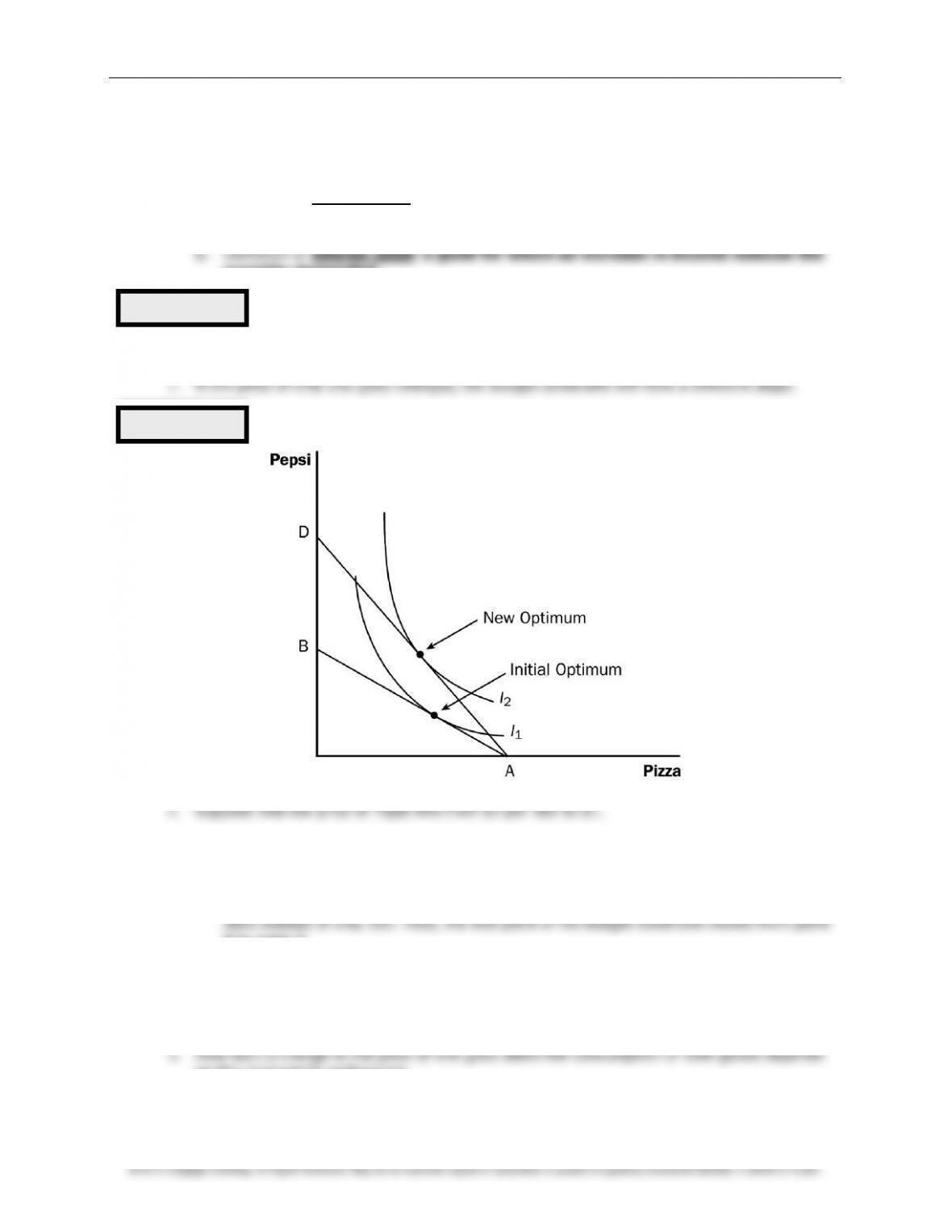

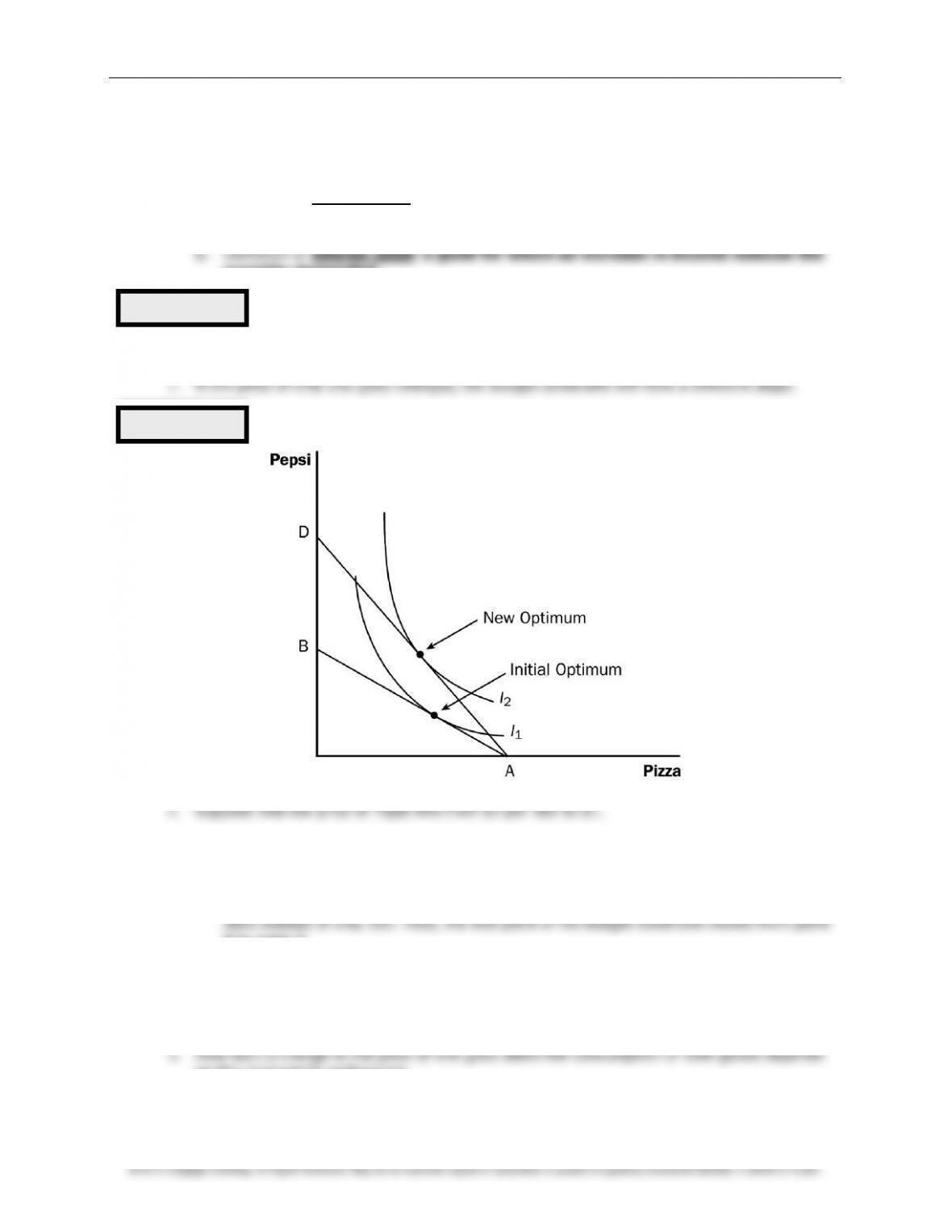

1. A change in income shifts the budget constraint.

b. Because the relative price of the two goods has not changed, the slope of the budget

constraint remains the same.

2. An increase in income means that the consumer can now reach a higher indifference curve.