Chapter 18 - Portfolio Performance Evaluation

Copyright © 2019 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent

of McGraw-Hill Education.

What is needed is a measure of abnormal performance. One can get more return in bull markets

by taking on more risk, this doesn’t mean the managers are adding value; can they generate good

returns consistently through time across different market cycles? It takes measures that

incorporate risk and it requires statistical work to make us believe the results are not just due to

chance.

How can managers generate abnormal performance? There are several means:

• Successful across asset allocations (time the market)

• Superior allocation within each asset class (weight sectors)

o Sectors or industries

o Overweight better performing sectors, underweight poorer performers

• Individual security selection (pick stocks)

o Pick the right stocks, those with performance better than expected

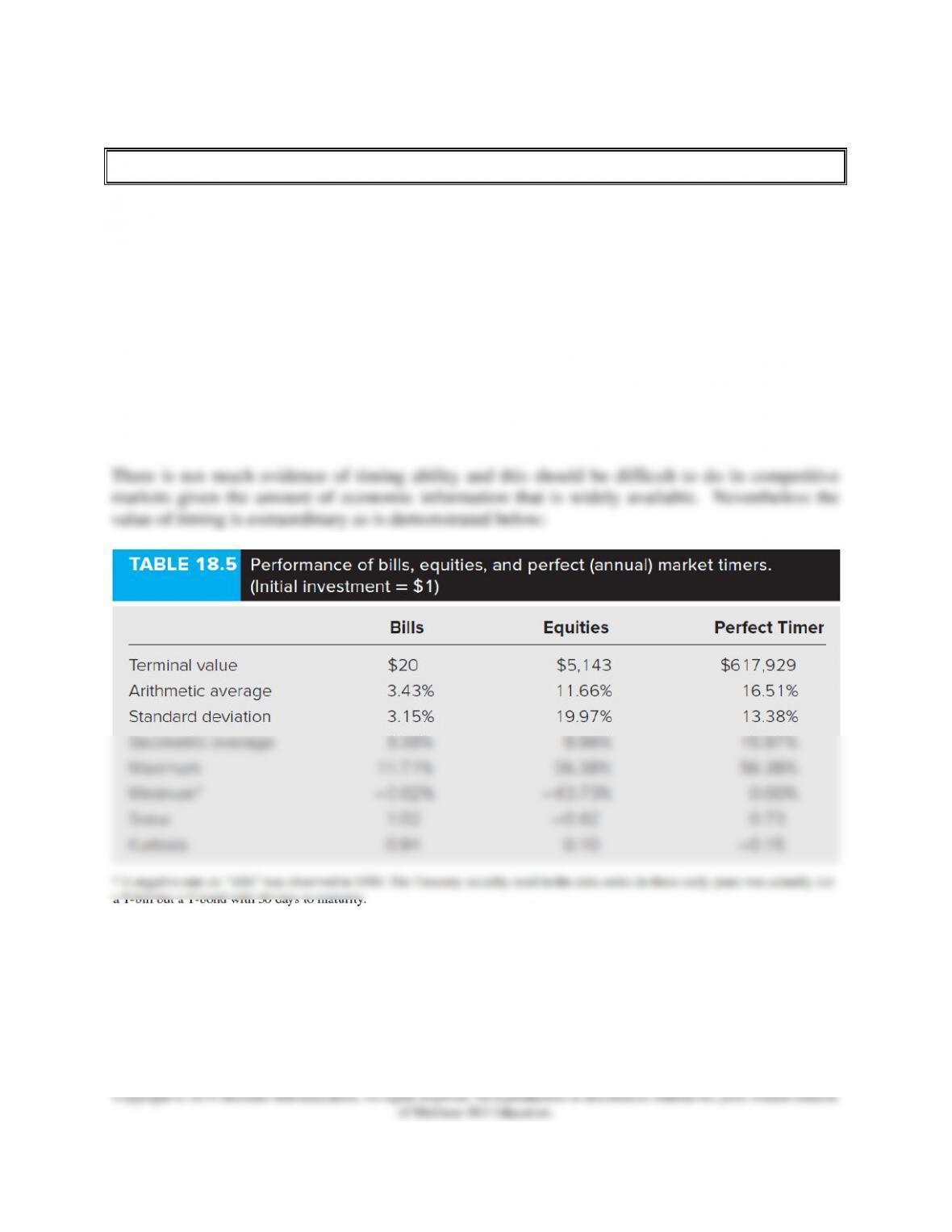

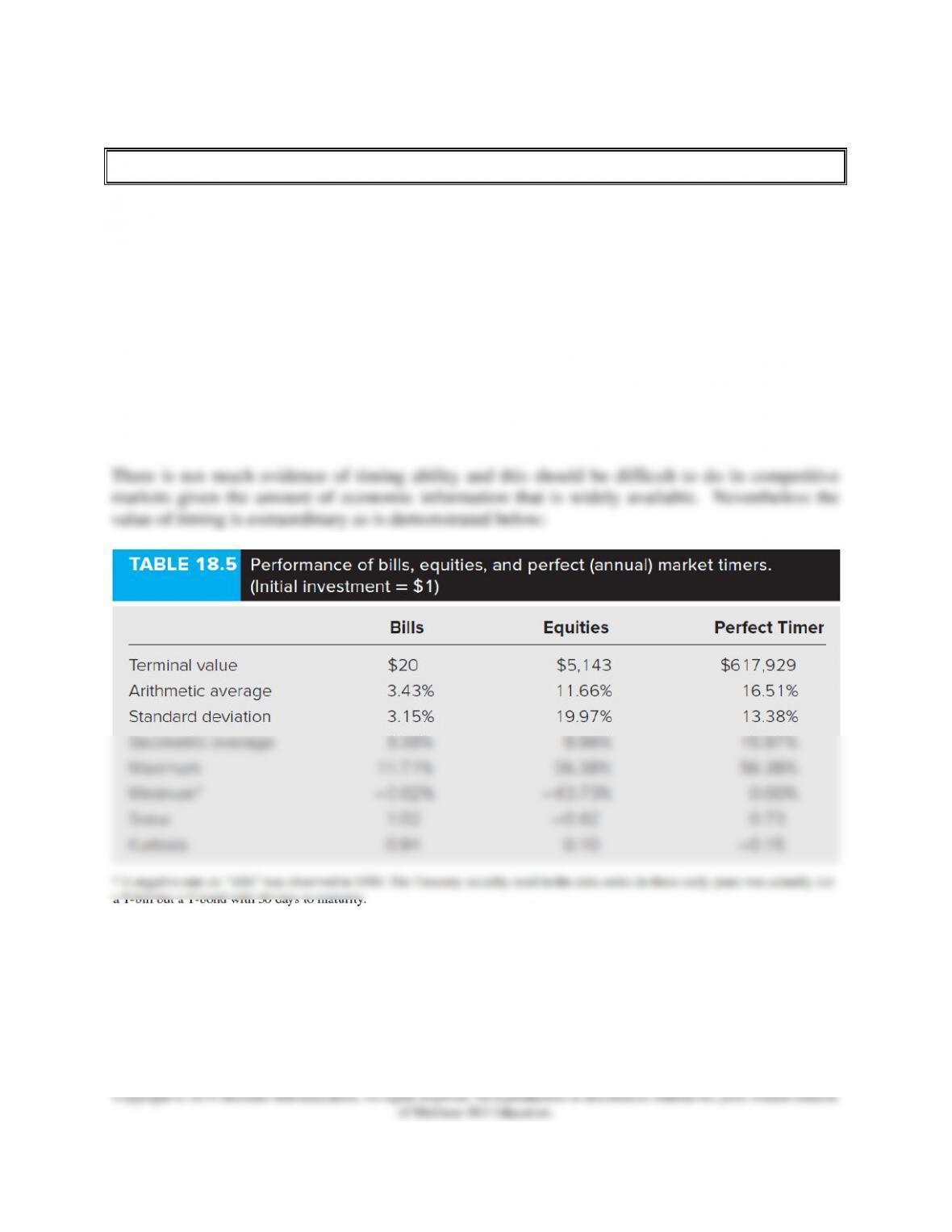

The most valuable activity and the toughest to do successfully is time the market.

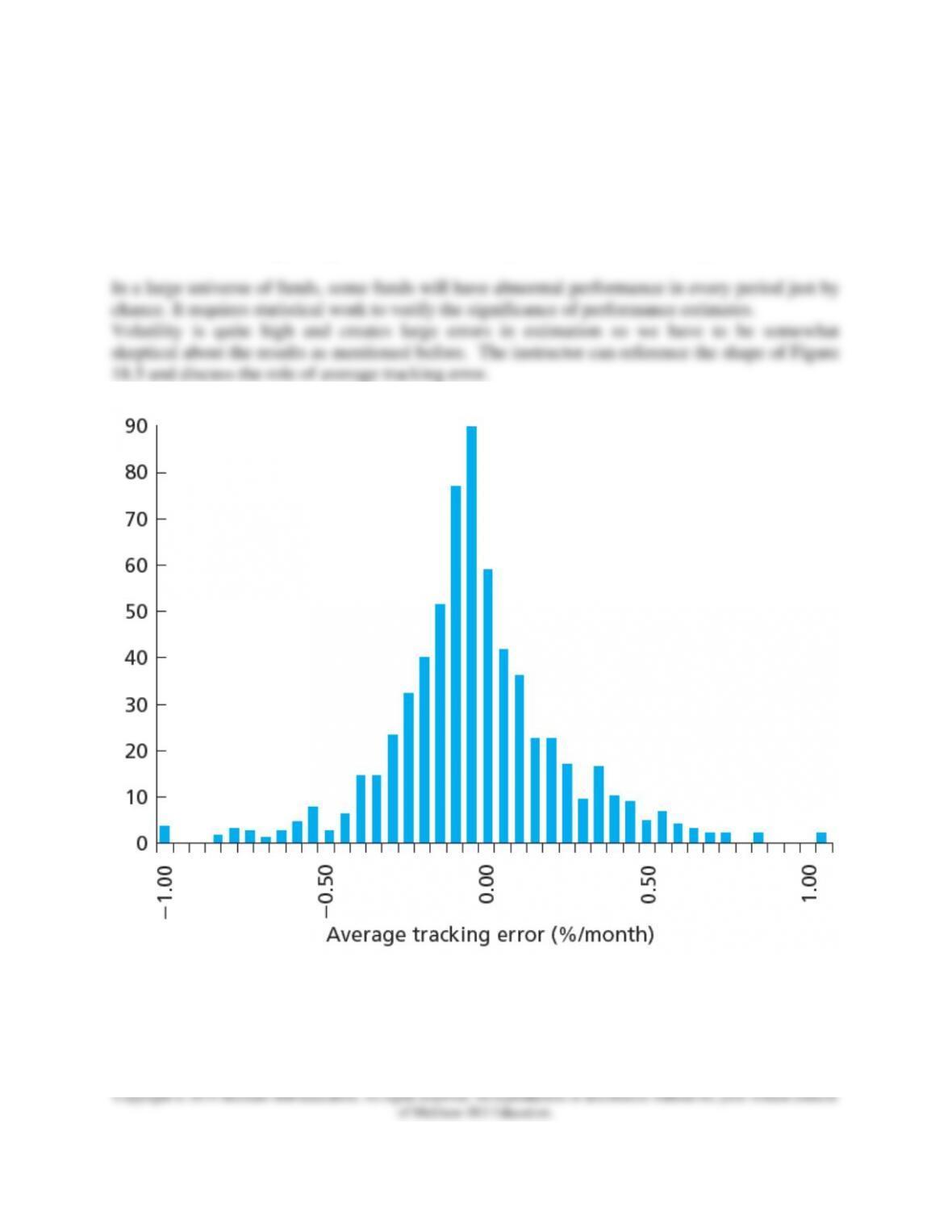

Obtaining an accurate estimate of risk-adjusted performance for a portfolio manager is difficult

for several reasons. First, in order to measure abnormal performance one needs an accurate

model of normal performance. Is a single index model an adequate measure of expected

performance or should a multi-index model be used? Second, most of the sound measures of

risk-adjusted returns require stability for the portfolio. Most portfolios are actively managed and

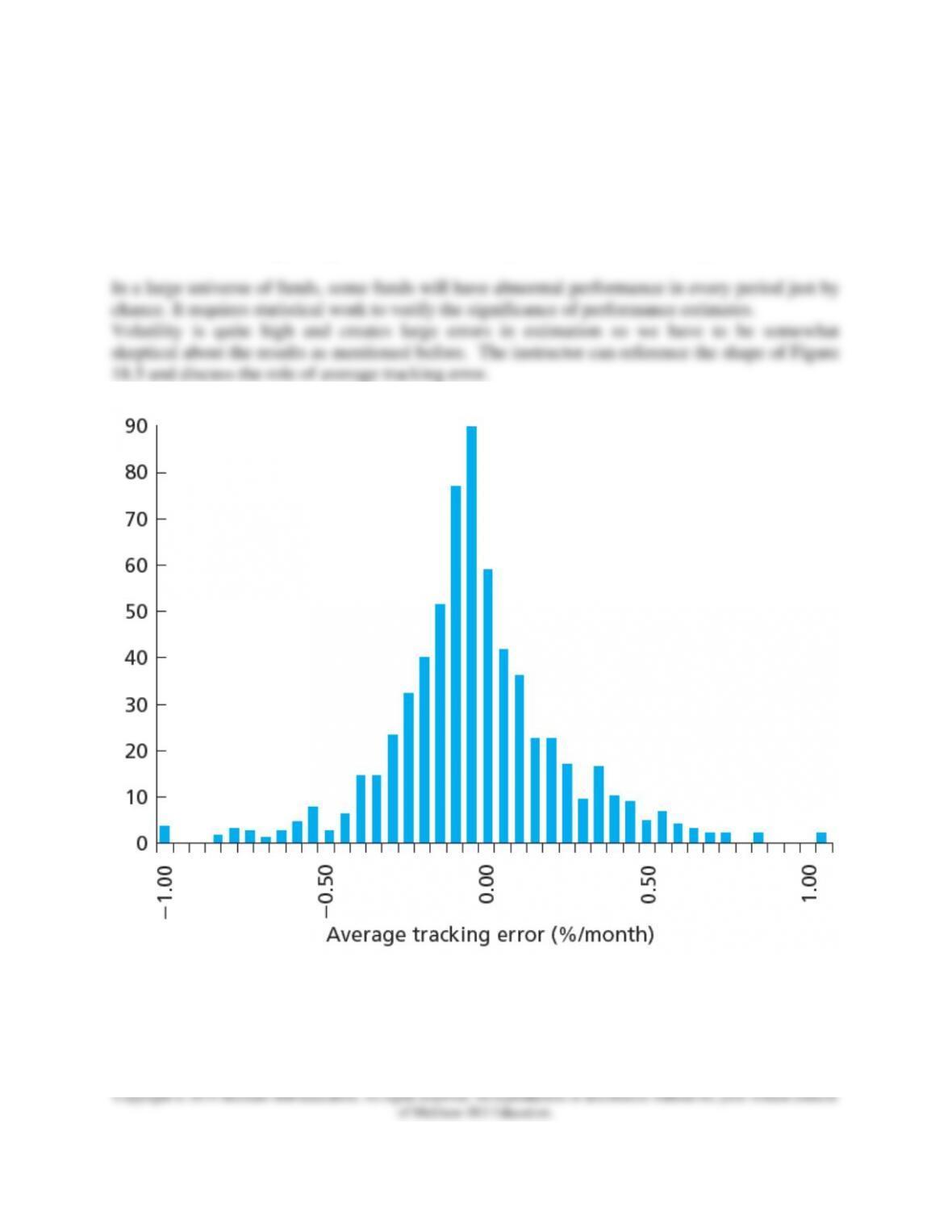

the stability assumptions are not met. Third, in competitive markets with significant volatility,

identifying the actual level of abnormal performance that is likely to occur is very difficult. The

probability of a Type 2 error is quite high.

Basic performance measurement compares portfolio performance to some benchmark portfolio.

The comparison to the benchmark is only appropriate if the risk is the same. Comparison groups

are very popular within the industry. It is the simplest method and involves comparing

performance of funds with similar objectives. The market model or index model approaches are

theoretically superior because they explicitly adjust for different levels of systematic risk.

The Sharpe Measure is also widely accepted in industry. This measure indicates the slope of the

CAL and it is based on the portfolio risk premium and the total risk of the portfolio as measured

by standard deviation.