Chapter 19 International Monetary Systems: An Historical Overview 145

© 2018 Pearson Education, Inc.

finance fiscal expenditures after the mid-1960s led to a loss of confidence in the dollar and the termination

of the dollar’s convertibility into gold. The analysis presented in the text demonstrates how the Bretton

Woods system forced countries to “import” inflation from the United States and shows that the breakdown

of the system occurred when countries were no longer willing to accept this burden.

Following the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system, many countries moved toward floating exchange

rates. In theory, floating exchange rates have four key advantages: They allow for independent monetary

policy; they are symmetric in terms of the costs of adjustment faced by deficit and surplus countries; they

act as automatic stabilizers that mitigate the effects of economic shocks; and they help maintain external

balance through stabilizing speculation that depreciates the currency of a country with a large current-

account deficit.

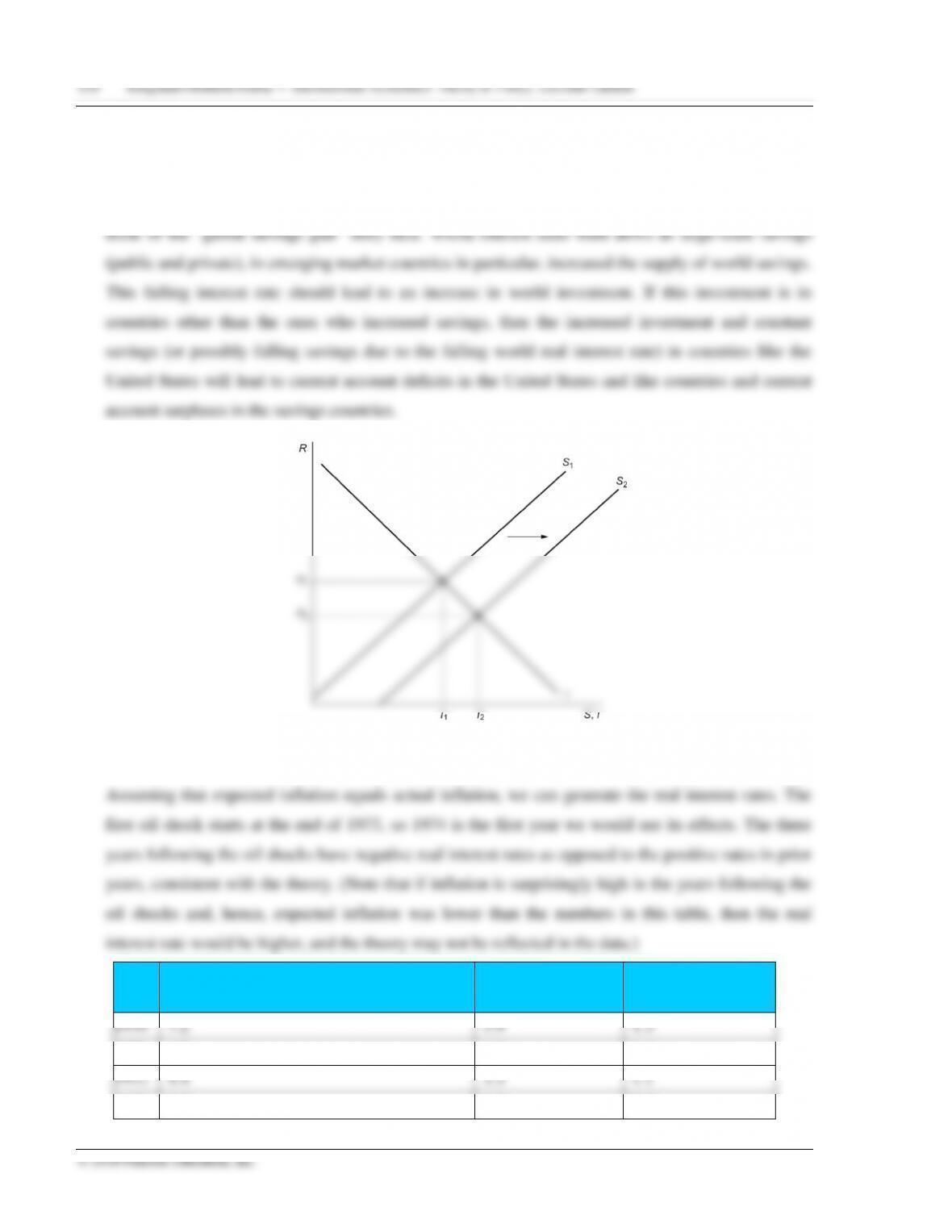

These advantages must be matched with the experience of countries running floating exchange rate

regimes. Floating exchange rates should give countries greater autonomy over monetary policy. However,

the evidence suggests that changes in monetary policy in one country do get transmitted across borders,

limiting autonomy. Second, exchange rates have become less stable. For example, in the mid 1970s, the

United States chose to pursue monetary expansion to fight a recession, whereas Germany and Japan

contracted their money supplies to counter inflation. As a result, the dollar sharply depreciated against

these currencies. The symmetry benefit of floating rates is also limited by the fact that the dollar still

serves as the world’s reserve currency, much as it did under Bretton Woods. Although floating rates do

work as automatic stabilizers, the effects may be unevenly distributed within countries. For example, the

U.S. fiscal expansion of the 1980s appreciated the dollar, limiting inflation overall. However, U.S. farmers

were hurt by this action as the stronger dollar weakened exports. With immobile factors of production,

these asymmetric effects can have long-run consequences. Finally, empirical evidence suggests that

external imbalances have actually increased since the adoption of floating exchange rates. The chapter

concludes with a discussion of policy coordination under floating exchange rates. For example, a large

country with a current-account deficit that attempts to reduce its imbalance could cause global deflation.

There is also a market failure at work here in that policies by one country have external effects. For

example, the 2007–2009 financial crisis sparked a number of fiscal expansions in countries. Increased

government spending in the United States, for example, helped lift demand not just in the United States

but in other countries as well. Because the benefits of fiscal expansion are not fully internalized (though

the costs are through accumulated budget deficits), there will be an inefficiently small expansion from a

global perspective. Thus, international policy coordination, even in a world of flexible exchange rates,

may still be warranted. This is especially relevant given the observation that given increased capital

mobility, fixed exchange rates may not even be an option for most countries in a world without