Chapter 17 Output and the Exchange Rate in the Short Run 121

appreciation to satisfy interest parity (for a given future expected exchange rate).

The effects of temporary policies, as well as the short-run and long-run effects of permanent policies, can

be studied in the context of the DD-AA model if we identify the expected future exchange rate with the

long-run exchange rate examined in Chapters 15 (4) and 16 (5). In line with this interpretation, temporary

policies are defined to be those that leave the expected exchange rate unchanged, while permanent policies

are those that move the expected exchange rate to its new long-run level. As in the analysis in earlier

chapters, in the long run, prices change to clear markets (if necessary). Although the assumptions concerning

the expectational effects of temporary and permanent policies are unrealistic as an exact description of an

economy, they are pedagogically useful because they allow students to grasp how differing market

expectations about the duration of policies can alter their qualitative effects. Students may find the

distinction between temporary and permanent, on the one hand, and between short run and long run on the

other, a bit confusing at first. It is probably worthwhile to spend a few minutes discussing this topic.

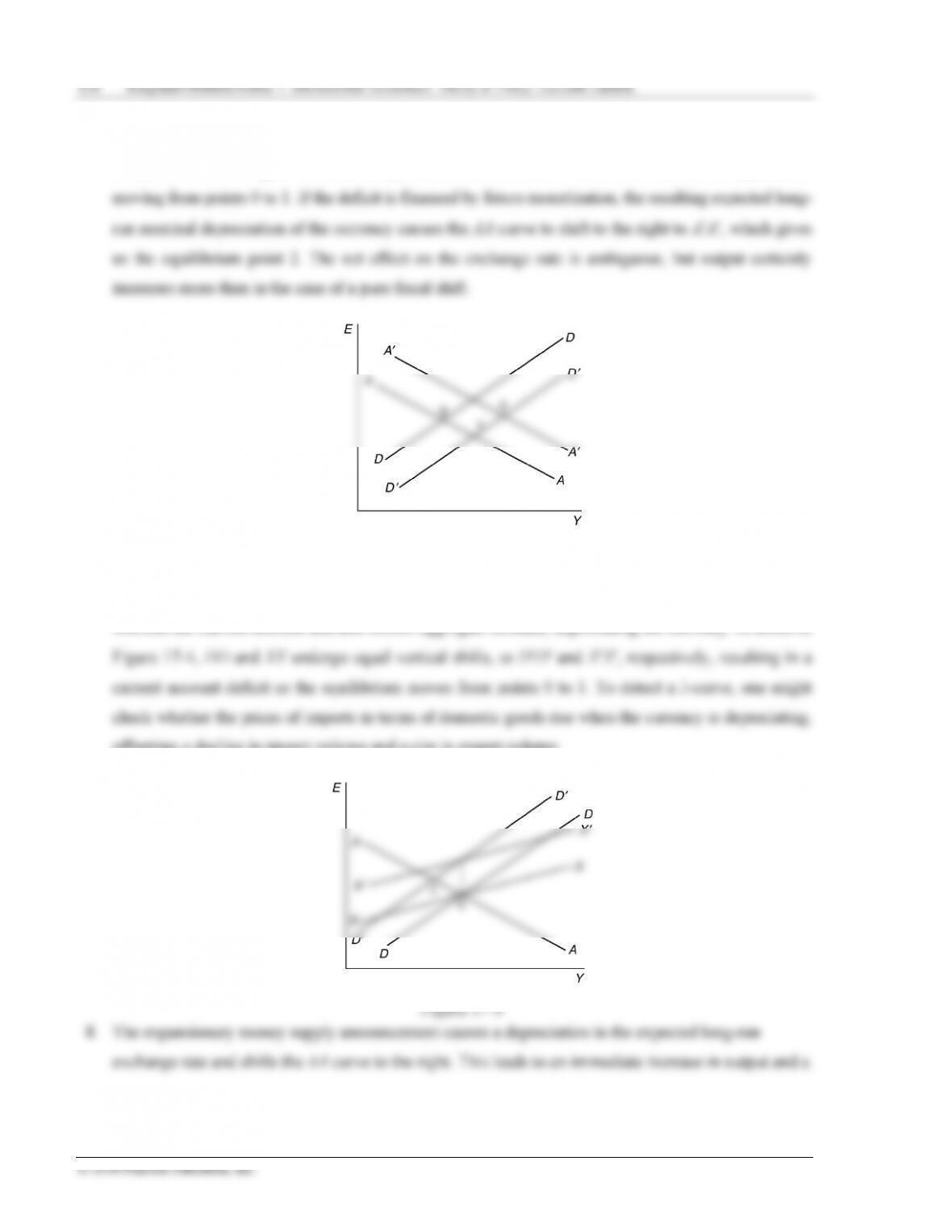

Both temporary and permanent increases in money supply expand output in the short run through exchange

rate depreciation. The long-run analysis of a permanent monetary change once again shows how the well-

known Dornbusch overshooting result can occur. Temporary expansionary fiscal policy raises output in

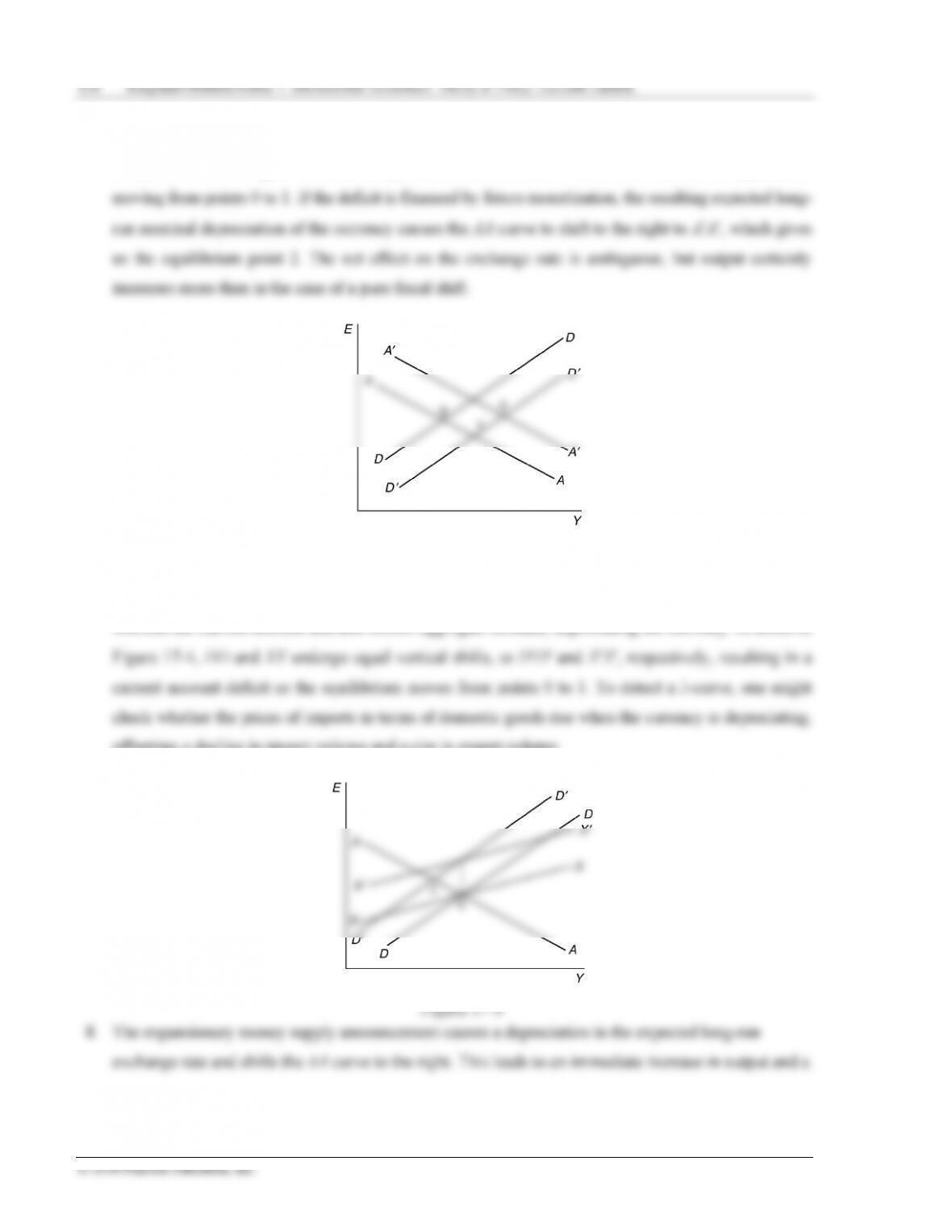

the short run and causes the exchange rate to appreciate. Permanent fiscal expansion, however, has no

effect on output even in the short run. The reason for this is that, given the assumptions of the model, the

currency appreciation in response to permanent fiscal expansion completely “crowds out” exports. This is

a consequence of the effect of a permanent fiscal expansion on the expected long-run exchange rate, which

shifts the asset-market equilibrium curve inward. This model can be used to explain the consequences of

U.S. fiscal and monetary policies between 1979 and 1984. The model explains the recession of 1982 and

the appreciation of the dollar as a result of tight monetary and loose fiscal policy.

The chapter concludes with some discussion of real-world modifications of the basic model. Recent

experience casts doubt on a tight, unvarying relationship between movements in the nominal exchange rate

and shifts in competitiveness and thus between nominal exchange rate movements and movements in the

trade balance as depicted in the DD-AA model. Exchange rate pass-through is less than complete and thus

nominal exchange rate movements are not translated one-for-one into changes in the real exchange rate.

Furthermore, the degree of exchange rate pass through will depend on the currency that exports are

invoiced in as well as whether an exchange rate change was caused by a change in output demand (less

pass-through) or a change in asset demand (more pass-through). Also, the current account may worsen

immediately after currency depreciation. This J-curve effect occurs because of time lags in deliveries and

because of low elasticities of demand in the short run as compared to the long run. The chapter contains a

discussion of the way in which the analysis of the model would be affected by the inclusion of incomplete

exchange rate pass-through and time-varying elasticities. Appendix 2 provides further information on trade