1. The cyclical behavior of key economic variables in other countries is similar to that in the

United States

2. Major industrial countries frequently have recessions and expansions at about the same time

3. Text Figure 8.13 illustrates common cycles for Japan, Canada, the United States, France,

Germany, and the United Kingdom

4. In addition, each economy faces small fluctuations that aren’t shared with other countries

Data Application

1. Coincident indexes are designed to help figure out the current state of the economy, while

leading indicators are designed to help predict peaks and troughs

2. The first index was developed by Mitchell and Burns of the NBER in the 1930s

3. The CFNAI is a coincident index produced by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago based on

85 macroeconomic variables; it is a coincident index that turns significantly negative in

recessions (text Figure 8.14)

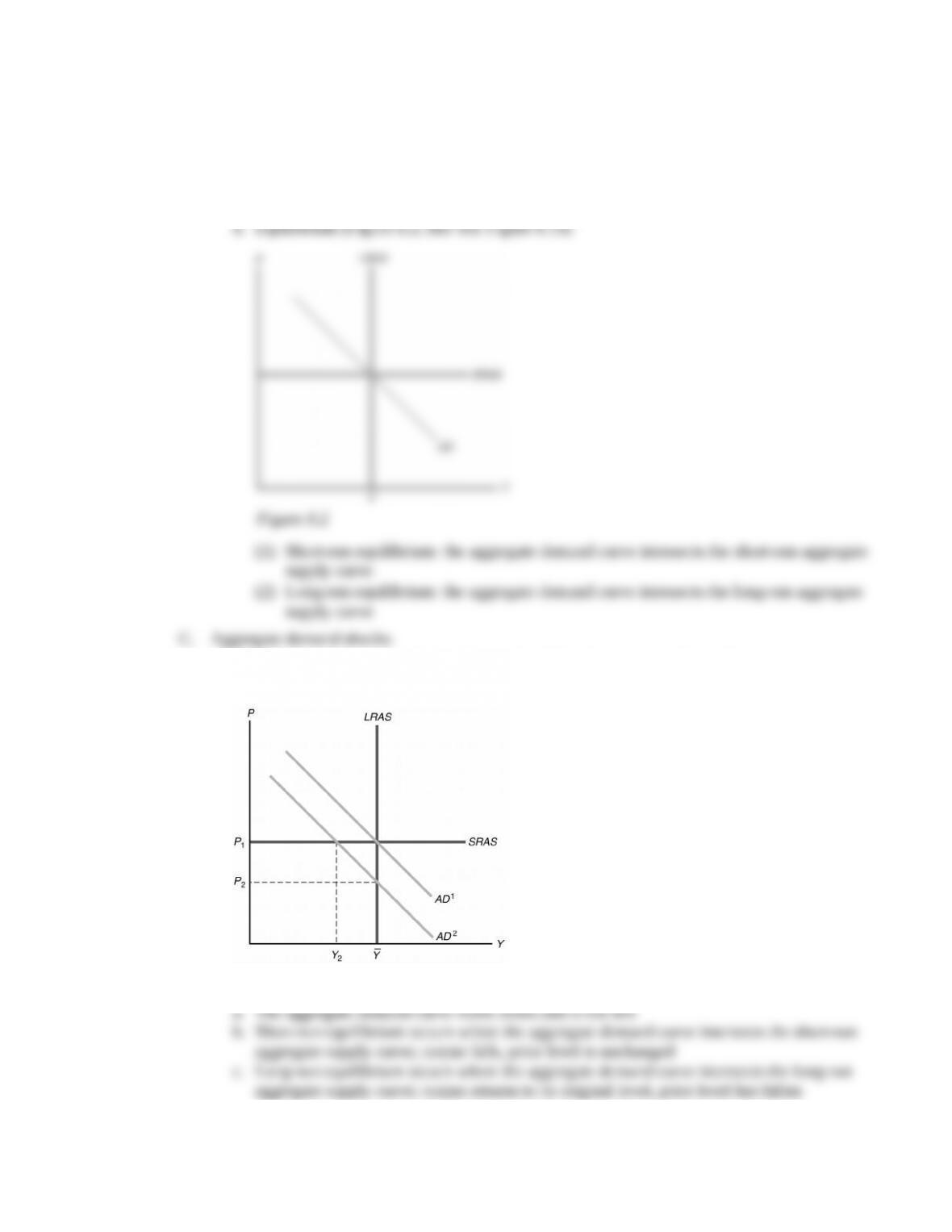

4. The ADS Business Conditions Index is a coincident index based on variables of different

frequencies (text Figure 8.15)

5. The CFNAI and ADS index perform similarly; the ADS is available more frequently but

doesn’t have a long track record

6. The Conference Board produces an index of leading economic indicators; a decline in the

index for two or three months in a row warns of recession danger

7. Problems with the leading indicators

a. Data are available promptly, but often revised later, so the index may give

8. Research by Diebold and Rudebusch showed that the index does not help forecast industrial

production in real time

9. In real time, the index sometimes gave no warning of recessions

a. The index gave no advance warning of the recession that began in December 1970

10. After the fact, the index of leading indicators is revised and appears to have predicted the

recessions well

11. Stock and Watson attempted to improve the index by creating some new indexes based on

newer statistical methods, but the results were disappointing as the new index failed to

12. Because recessions may be caused by sudden shocks, the search for a good index of leading

indicators may be fruitless

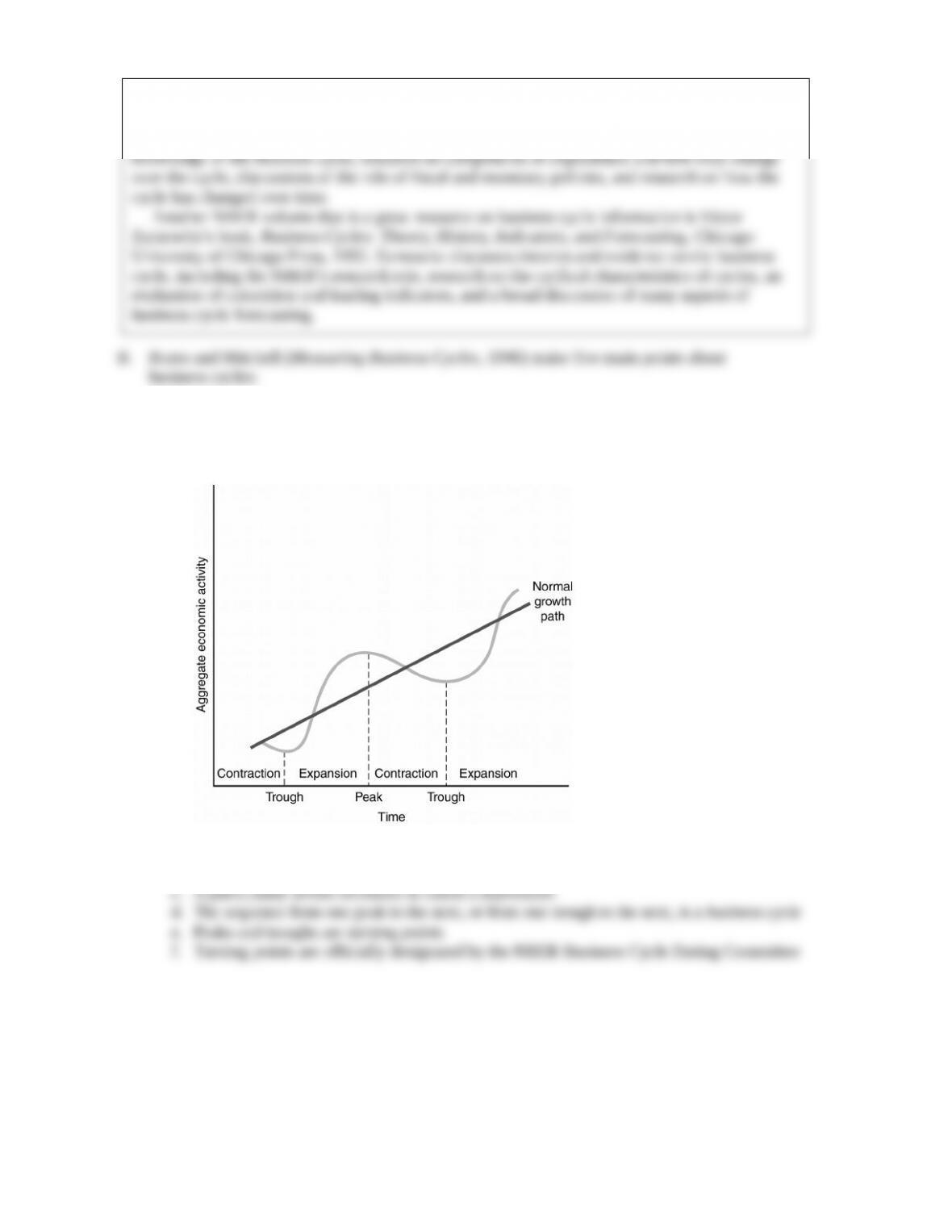

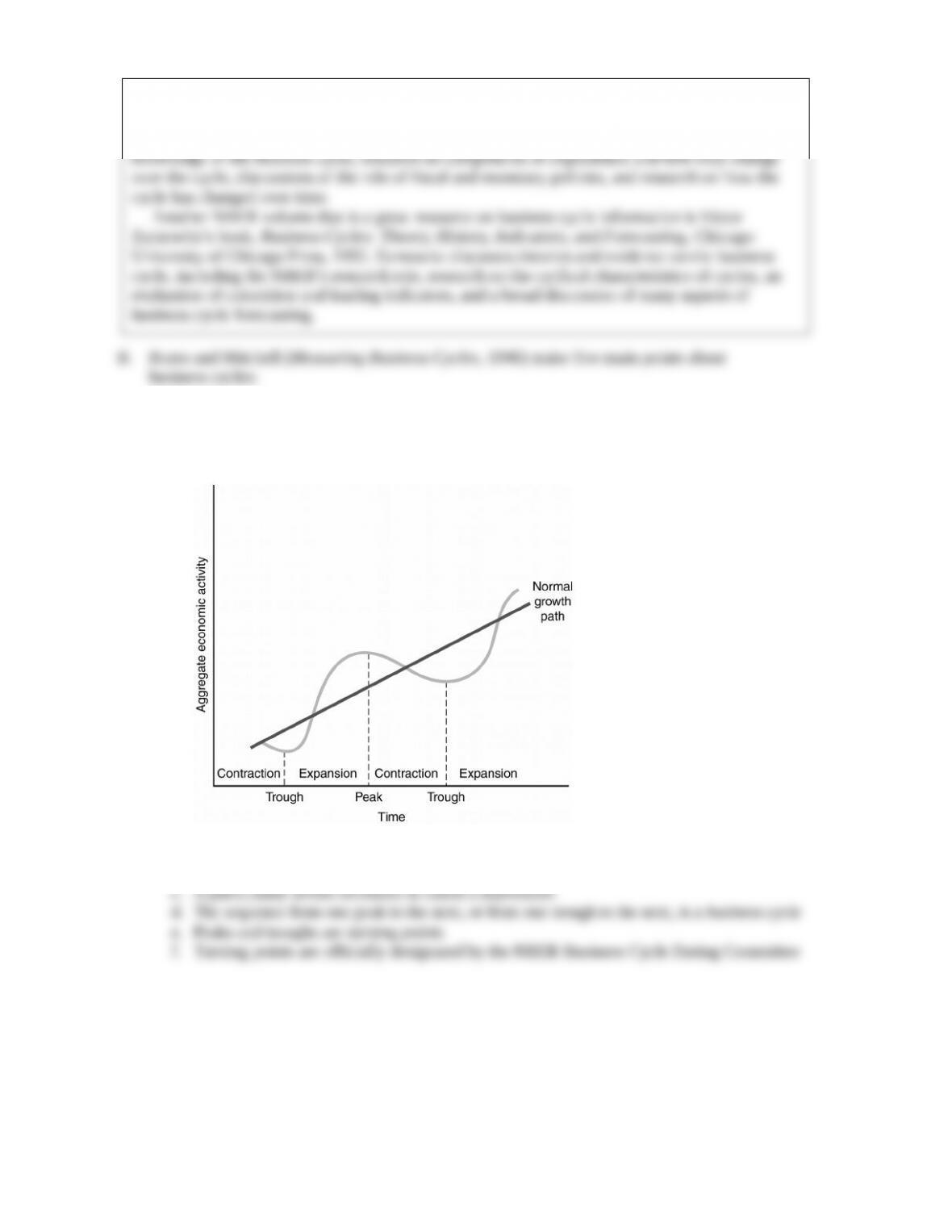

1. Output varies over the seasons: highest in the fourth quarter, lowest in the first quarter