6. Younger people, who were more likely to face binding borrowing constraints, increased

their purchases on credit cards the most of any group in response to the tax rebate

7. People with high credit limits also tended to pay off more of their balances and spent less, as

they were less likely to face binding borrowing constraints and behaved more in the manner

8. New evidence on the tax rebates in 2008 and 2009 was provided in a research paper by

Parker et al., who found that consumers spent 50%-90% of the tax rebates, which is

1. Investment fluctuates sharply over the business cycle, so we need to understand investment

to understand the business cycle

2. Investment plays a crucial role in economic growth

B. The desired capital stock

1. Desired capital stock is the amount of capital that allows firms to earn the largest expected profit

2. Desired capital stock depends on costs and benefits of additional capital

3. Since investment becomes capital stock with a lag, the benefit of investment is the future

marginal product of capital (MPKf)

4. The user cost of capital

a. Example of Kyle’s Bakery: cost of capital, depreciation rate, and expected real interest rate

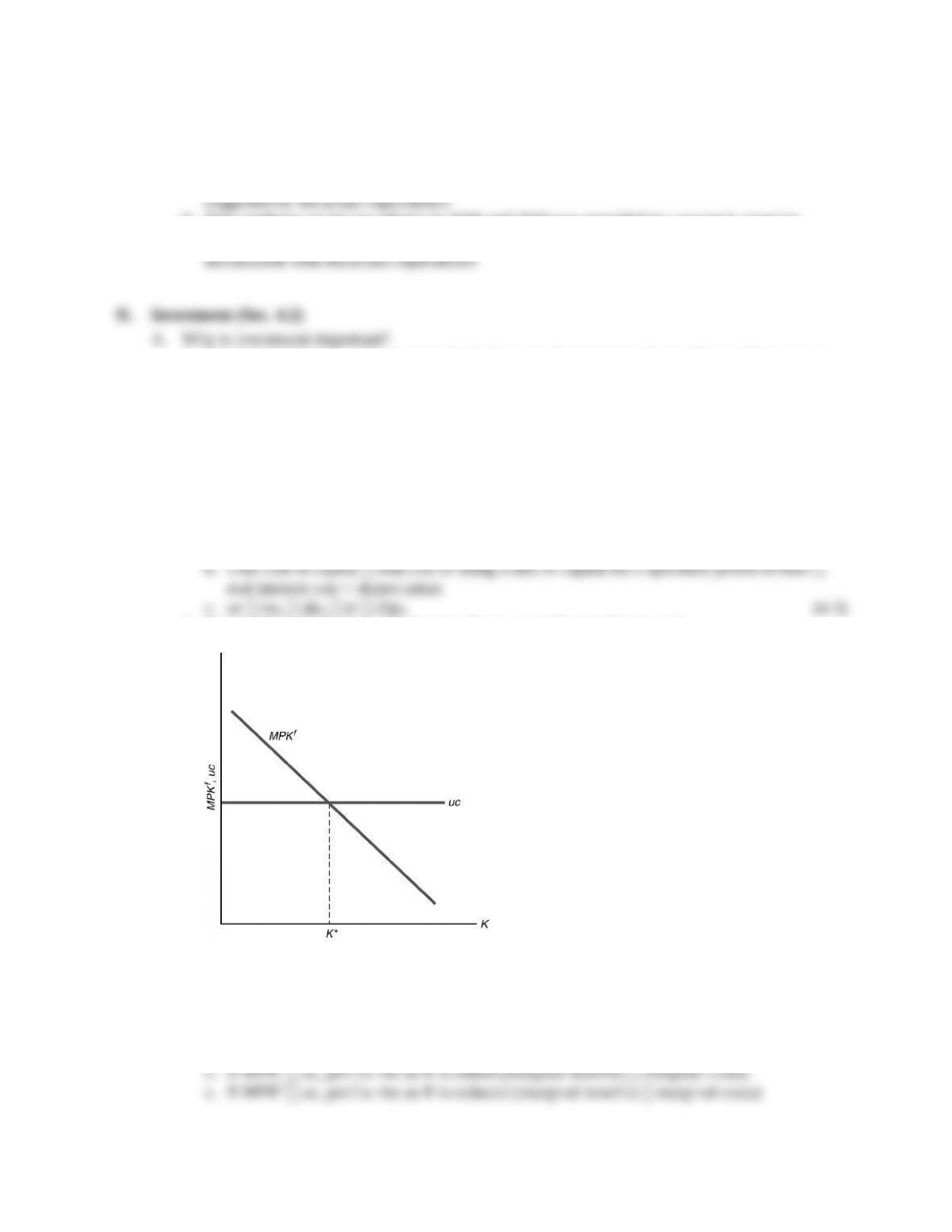

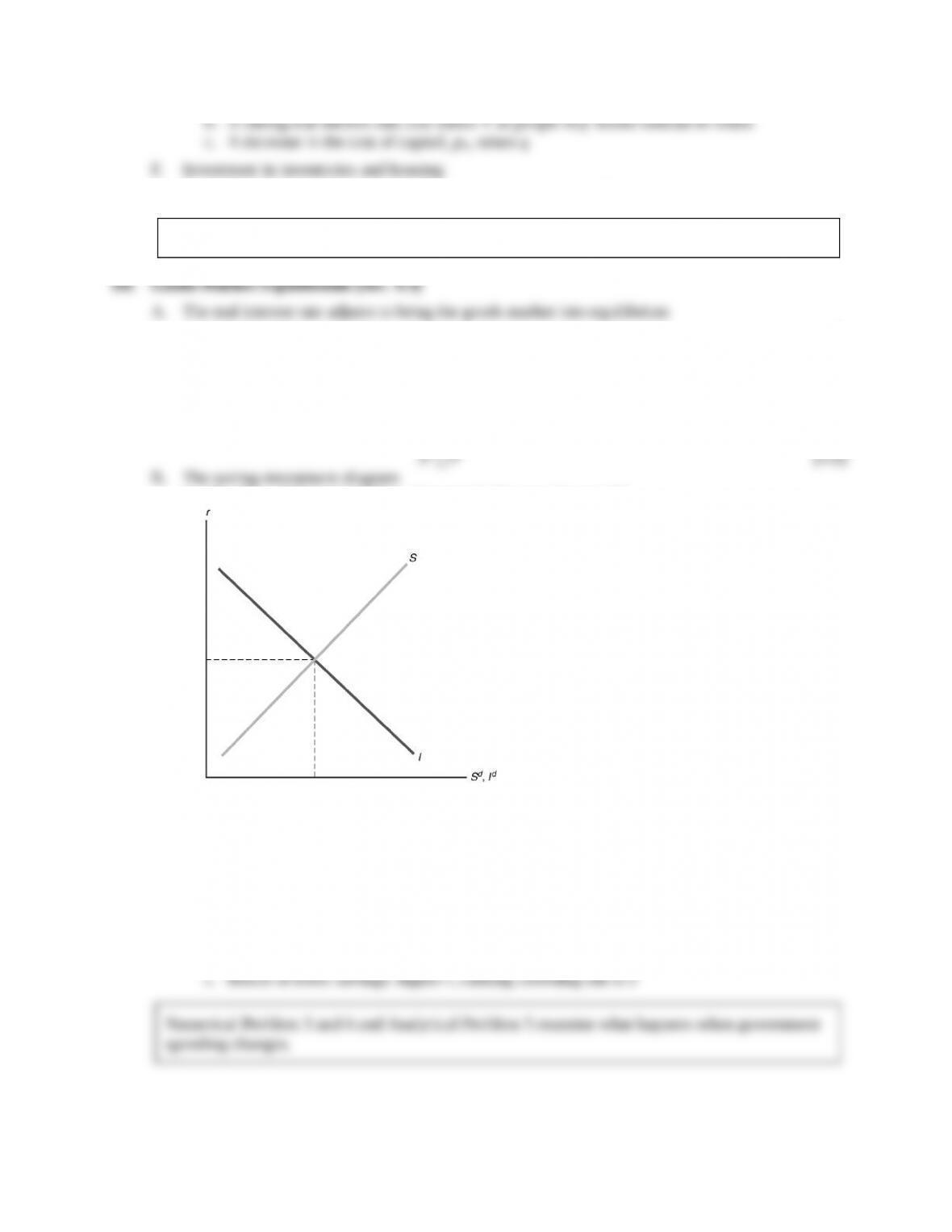

5. Determining the desired capital stock (Figure 4.1; like text Figure 4.3)

Figure 4.1

a. Desired capital stock is the level of capital stock at which MPKf uc

b. MPKf falls as K rises due to diminishing marginal productivity

c. uc doesn’t vary with K, so is a horizontal line