V. Unemployment (Sec. 3.5)

1. Categories: employed, unemployed, not in the labor force

2. Labor Force Employed Unemployed

3. Unemployment Rate Unemployed/Labor Force

4. Table 3.4 shows current data

Data Application

The unemployment rate jumped up sharply in January 1994, not because of any true change in

the labor market, but merely because the Bureau of Labor Statistics changed the survey with

4. Participation Rate Labor Force/Adult Population

5. Employment Ratio Employed/Adult Population

Analytical Problem 6 tests students’ ability to use these different measures.

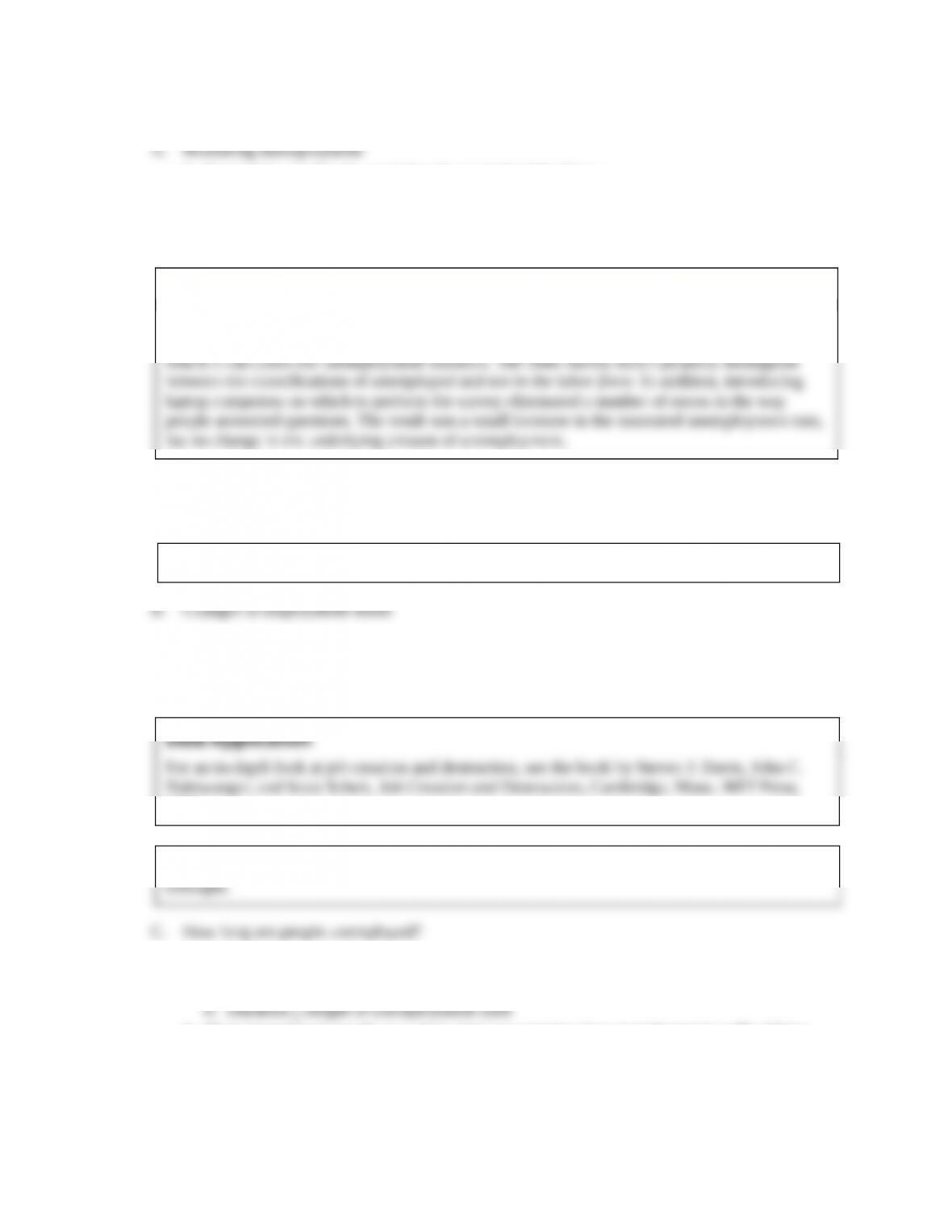

1. Flows between categories (text Fig. 3.12)

2. Discouraged workers: people who have become so discouraged by lack of success at finding

a job that they stop searching

1996.

Numerical Problems 7 and 8 are quantitative exercises using the unemployment and employment

1. Most unemployment spells are of short duration

a. Unemployment spell period of time an individual is continuously unemployed

2. Most unemployed people on a given date are experiencing unemployment spells of long

duration

3. Reconciling 1 and 2—numerical example: