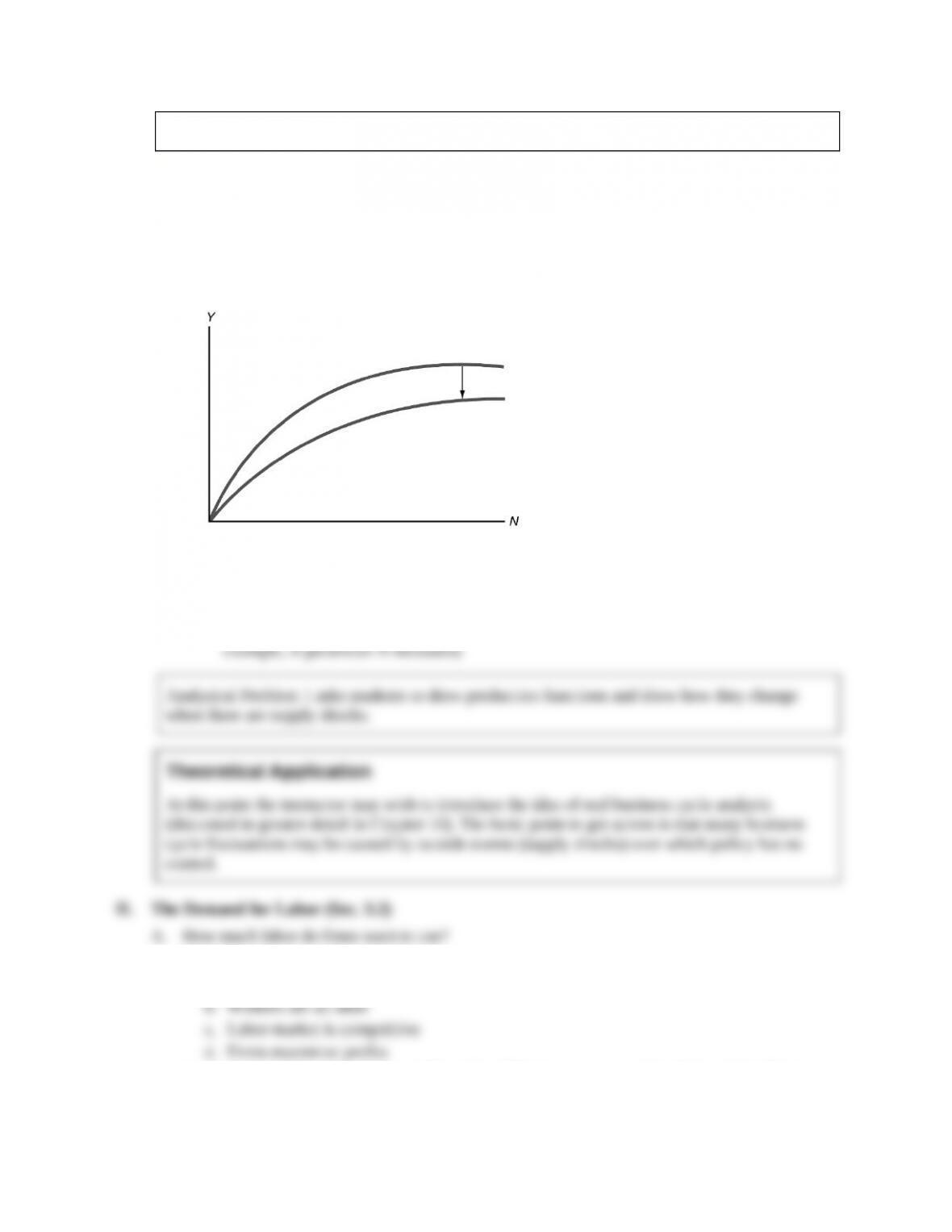

1. Note: A change in the wage causes a movement along the labor demand curve, not a shift of

the curve

2. Supply shocks: Beneficial supply shock raises MPN, so shifts labor demand curve to the

right; opposite for adverse supply shock

3. Size of capital stock: Higher capital stock raises MPN, so shifts labor demand curve to the

right; opposite for lower capital stock

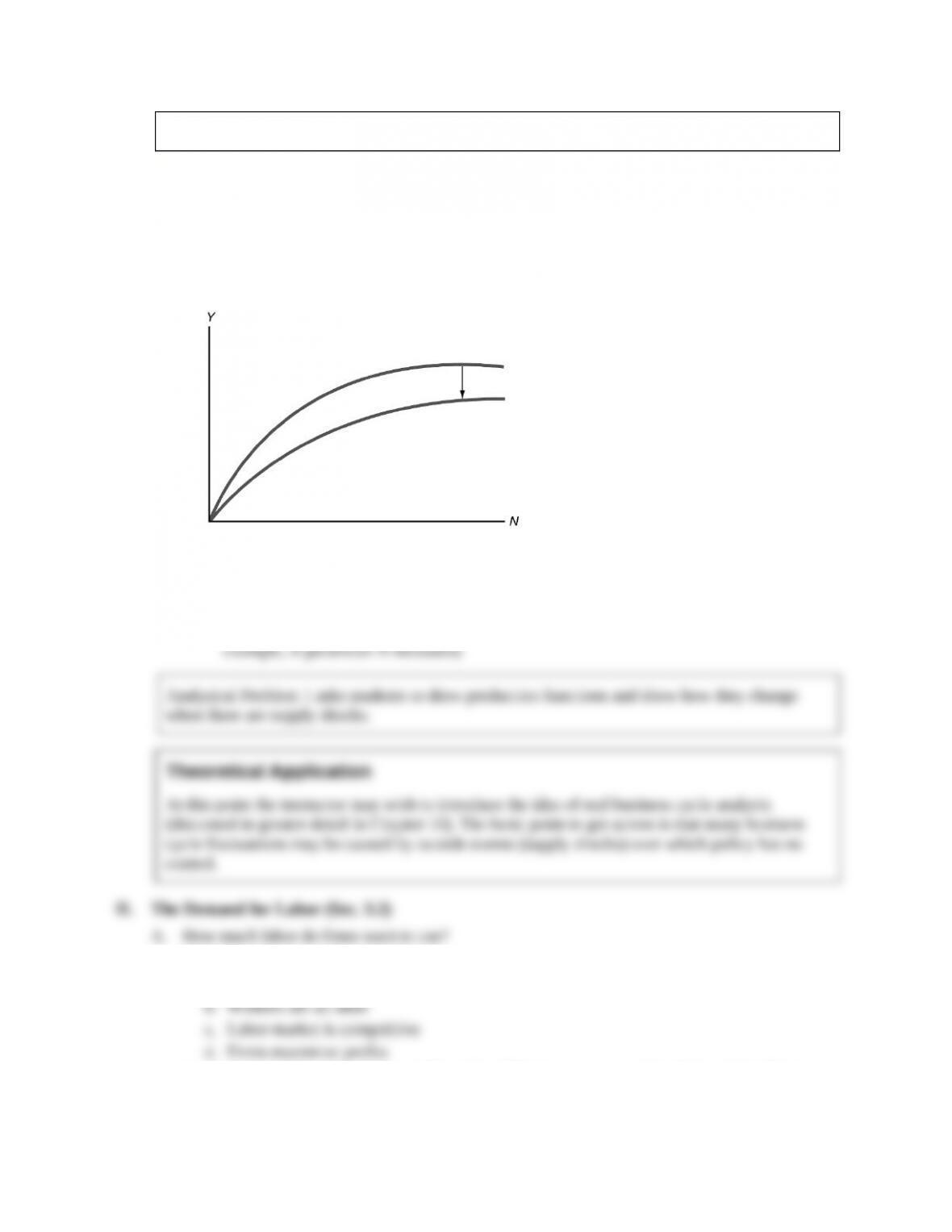

1. Aggregate labor demand is the sum of all firms’ labor demand

2. Same factors (supply shocks, size of capital stock) that shift firms’ labor demand cause

shifts in aggregate labor demand

1. Aggregate supply of labor is sum of individuals’ labor supply

2. Labor supply of individuals depends on labor-leisure choice

B. The income-leisure trade-off

1. Utility depends on consumption and leisure

2. Need to compare costs and benefits of working another day

a. Costs: Loss of leisure time

3. If benefits of working another day exceed costs, work another day

4. Keep working additional days until benefits equal costs

C. Real wages and labor supply

1. An increase in the real wage has offsetting income and substitution effects

a. Substitution effect of a higher real wage: Higher real wage encourages work, since the