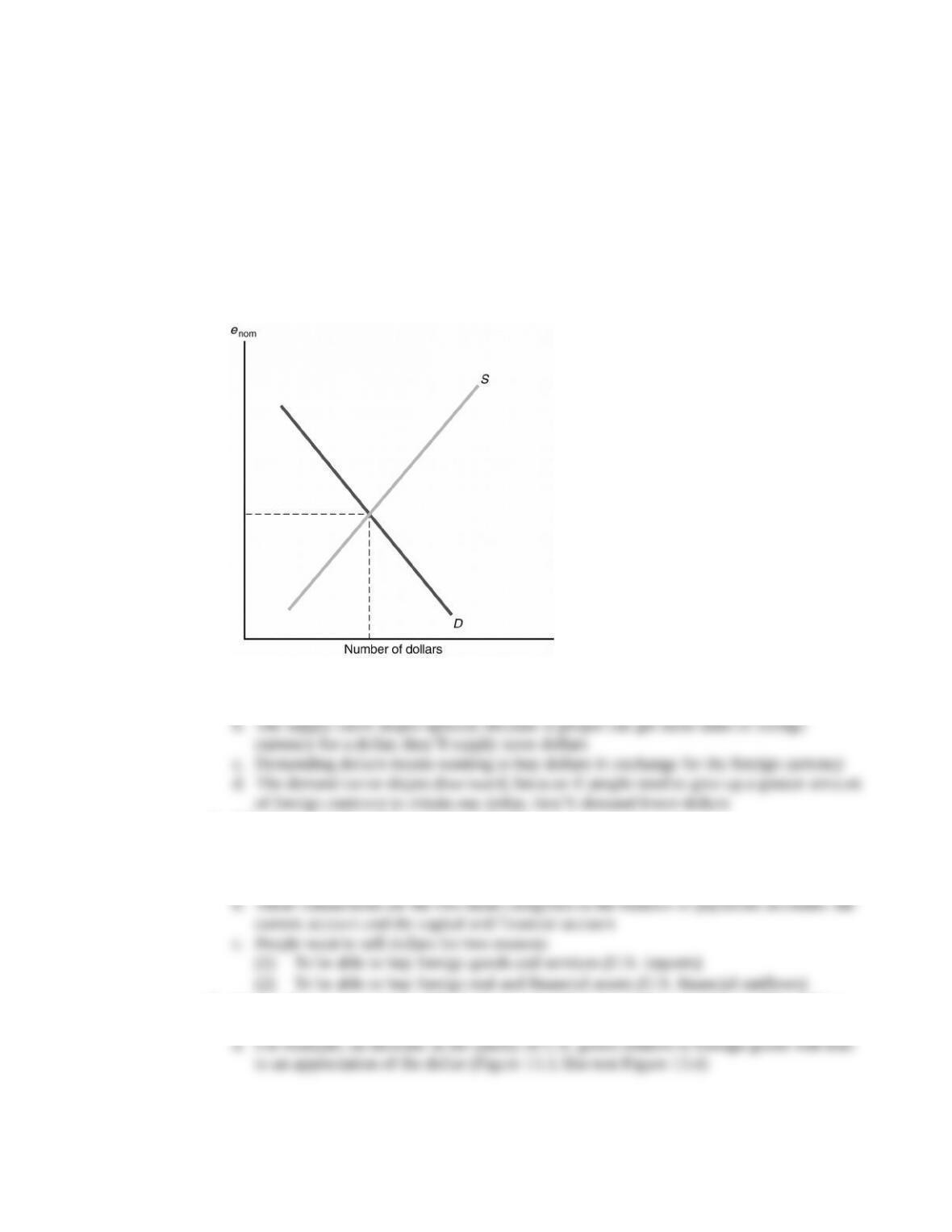

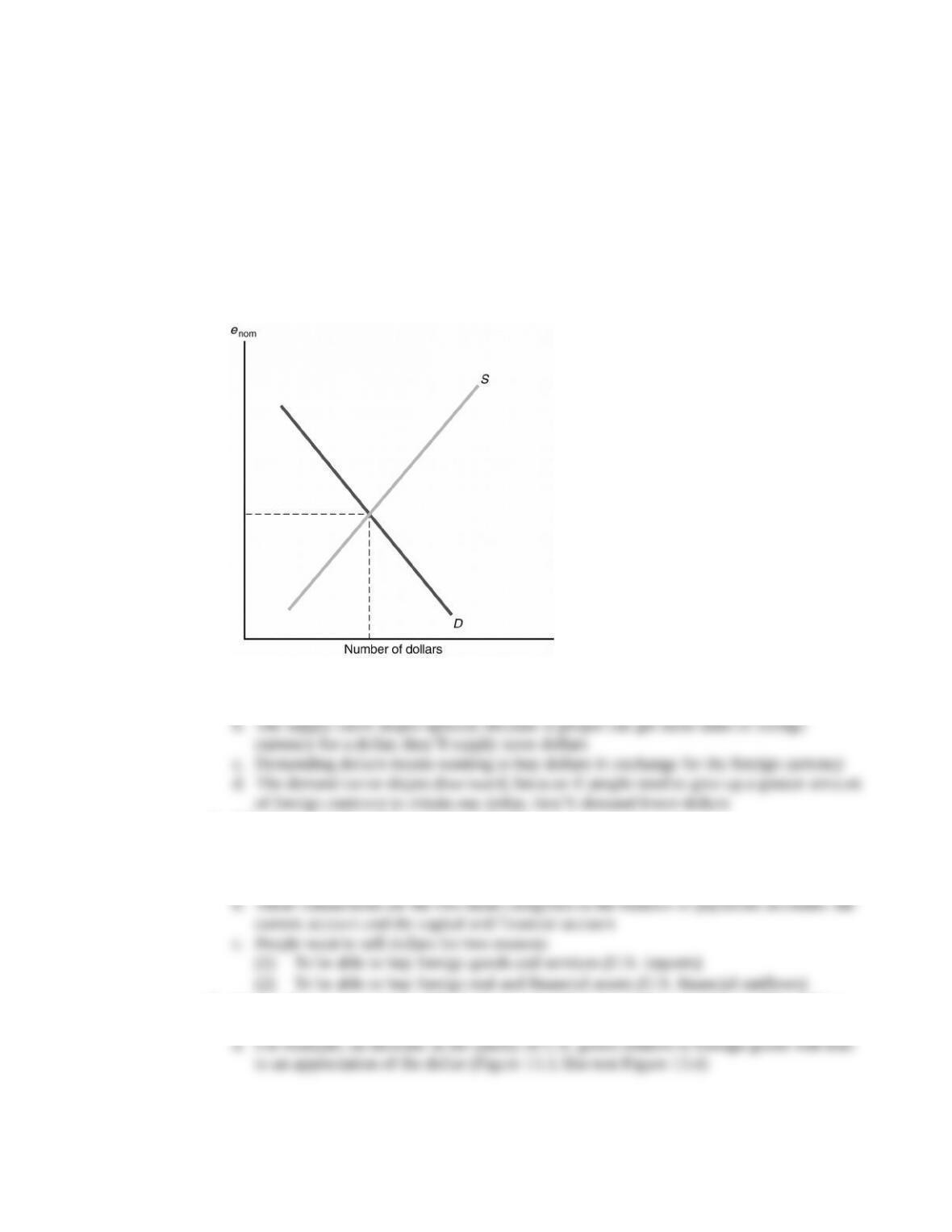

1. Trading in currencies occurs around-the-clock, since some market is open in some country

any time of day

2. The spot rate is the rate at which one currency can be traded for another immediately

3. The forward rate is the rate at which one currency can be traded for another at a fixed date

in the future (for example, 30, 90, or 180 days from now)

4. A pattern of rising forward rates suggests that people expect the spot rate to be rising in the

future

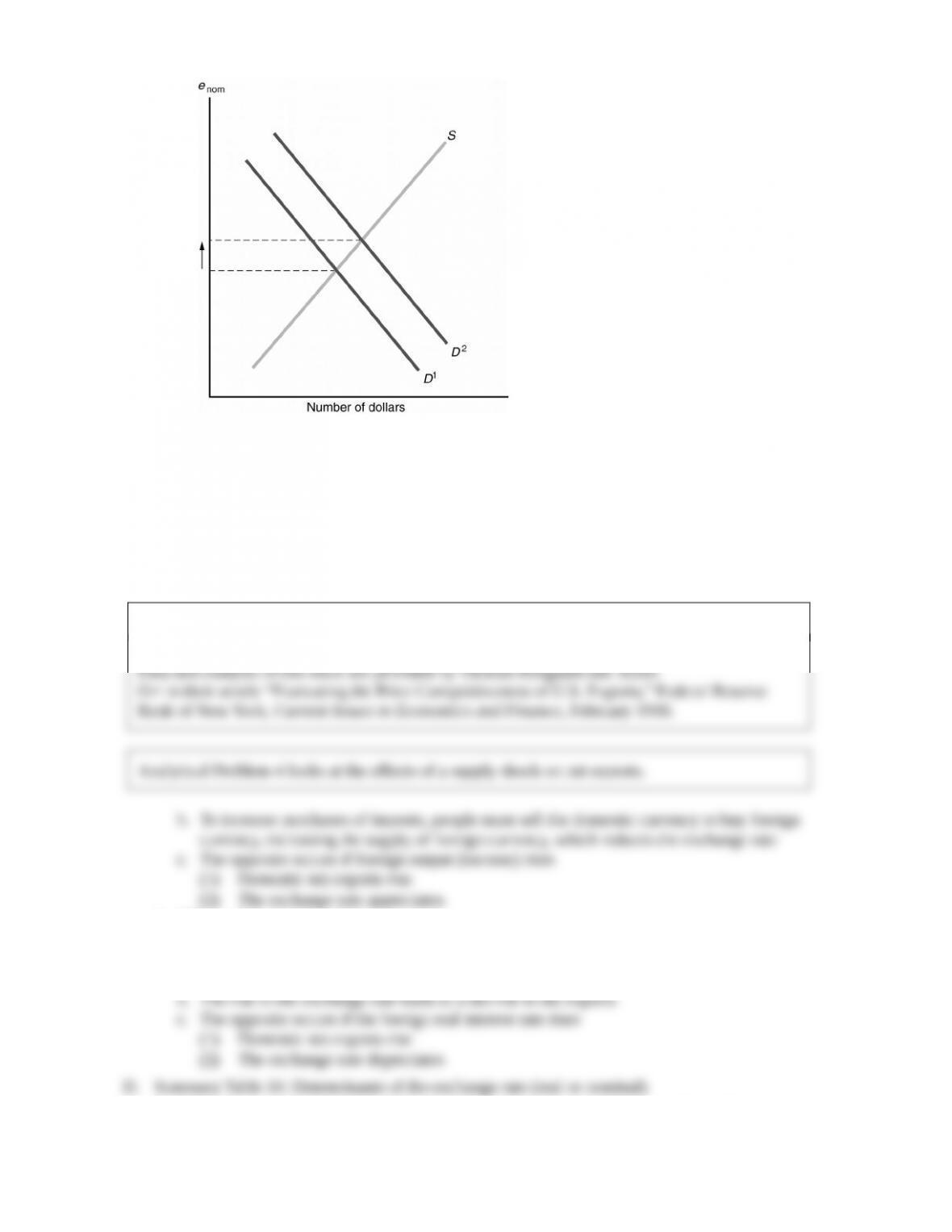

1. The real exchange rate tells you how much of a foreign good you can get in exchange for

one unit of a domestic good

2. If the nominal exchange rate is 80 yen per dollar, and it costs 800 yen to buy a hamburger in

Tokyo compared to 2 dollars in New York, the price of a U.S. hamburger relative to a

3. The real exchange rate is the price of domestic goods relative to foreign goods, or

e enomP/PFor (13.1)

4. To simplify matters, we’ll assume that each country produces a unique good

5. In reality, countries produce many goods, so we must use price indexes to get P and PFor

6. If a country’s real exchange rate is rising, its goods are becoming more expensive relative to

the goods of the other country

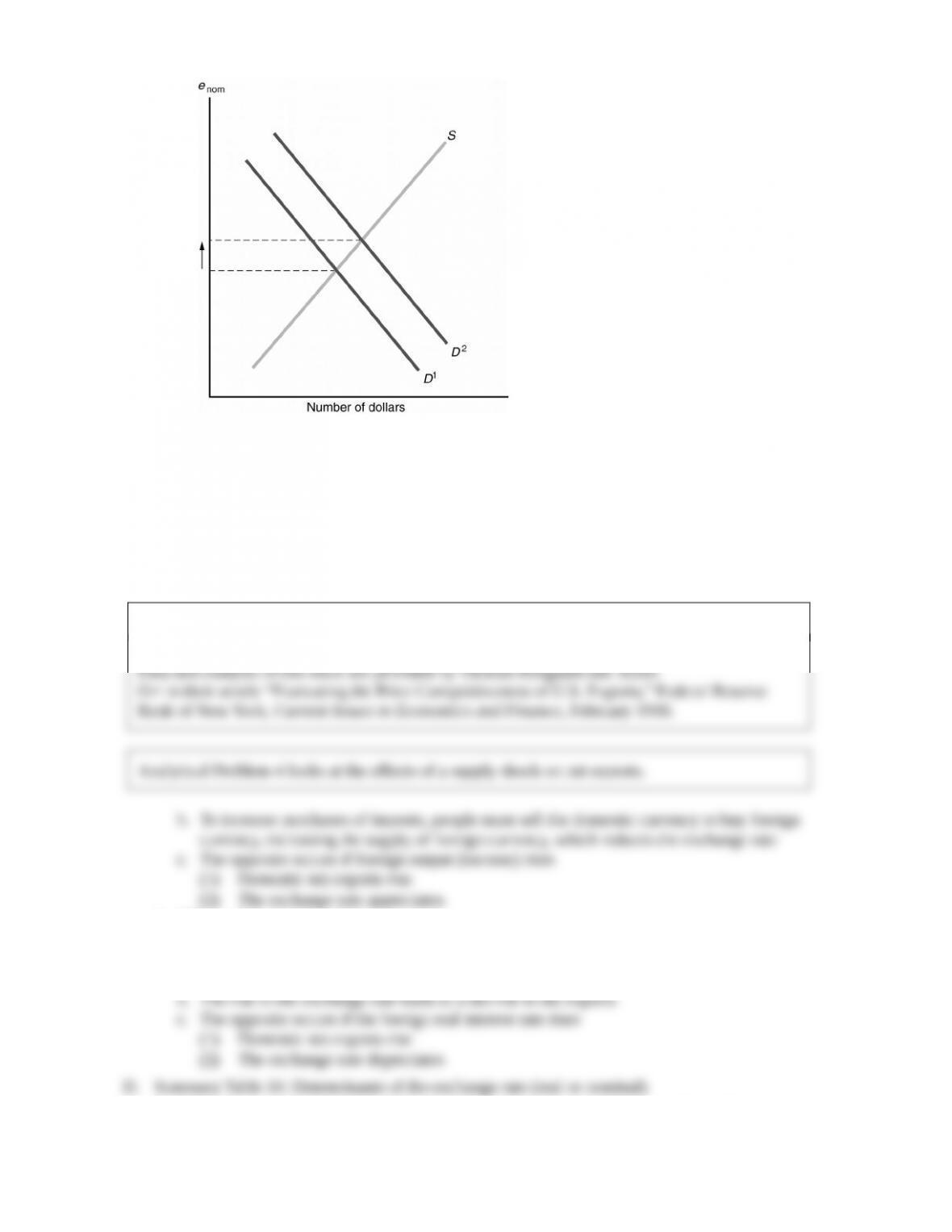

1. In a flexible-exchange-rate system, when enom falls, the domestic currency has undergone a

nominal depreciation (or it has become weaker); when enom rises, the domestic currency has

2. In a fixed-exchange-rate system, a weakening of the currency is called a devaluation, a

strengthening is called a revaluation

3. We also use the terms real appreciation and real depreciation to refer to changes in the real

exchange rate

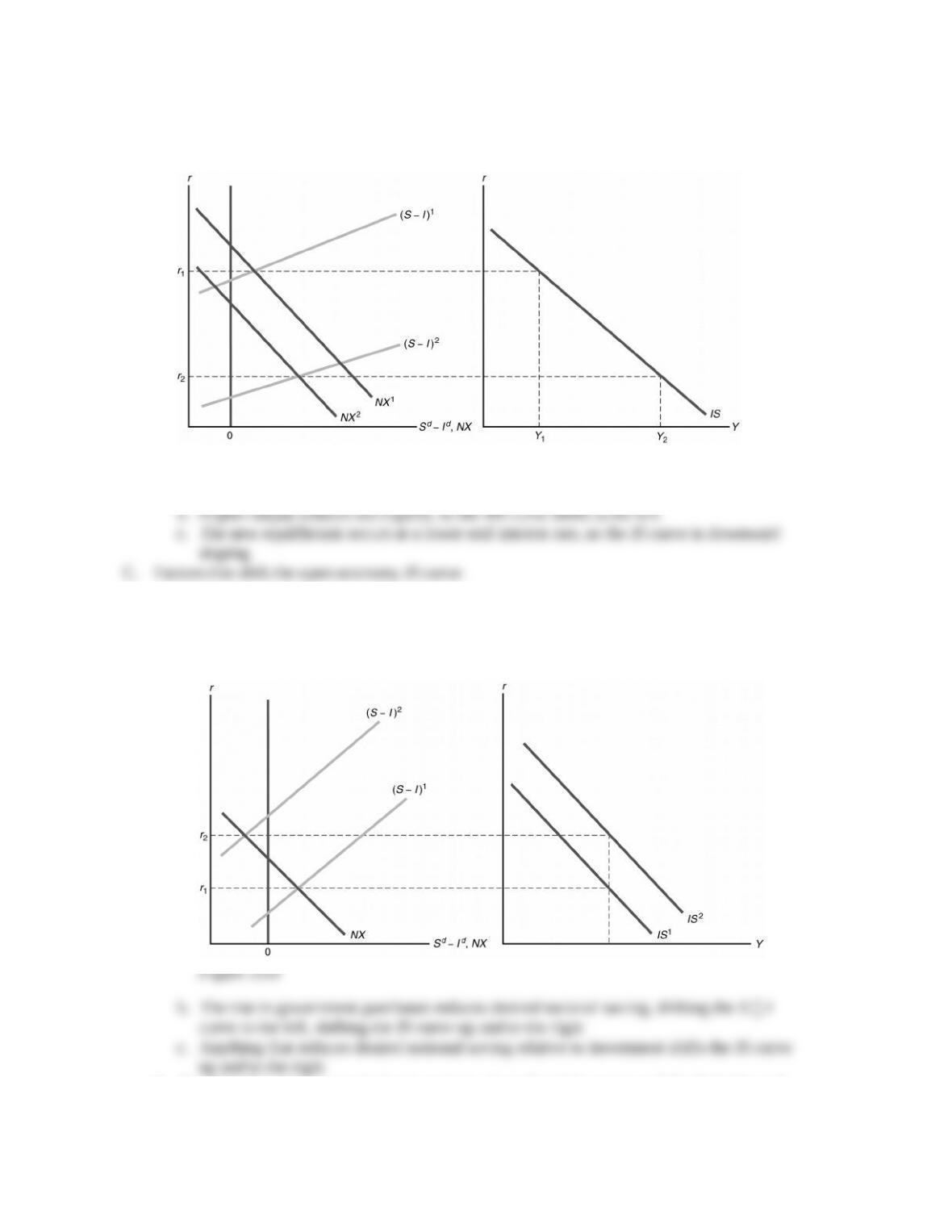

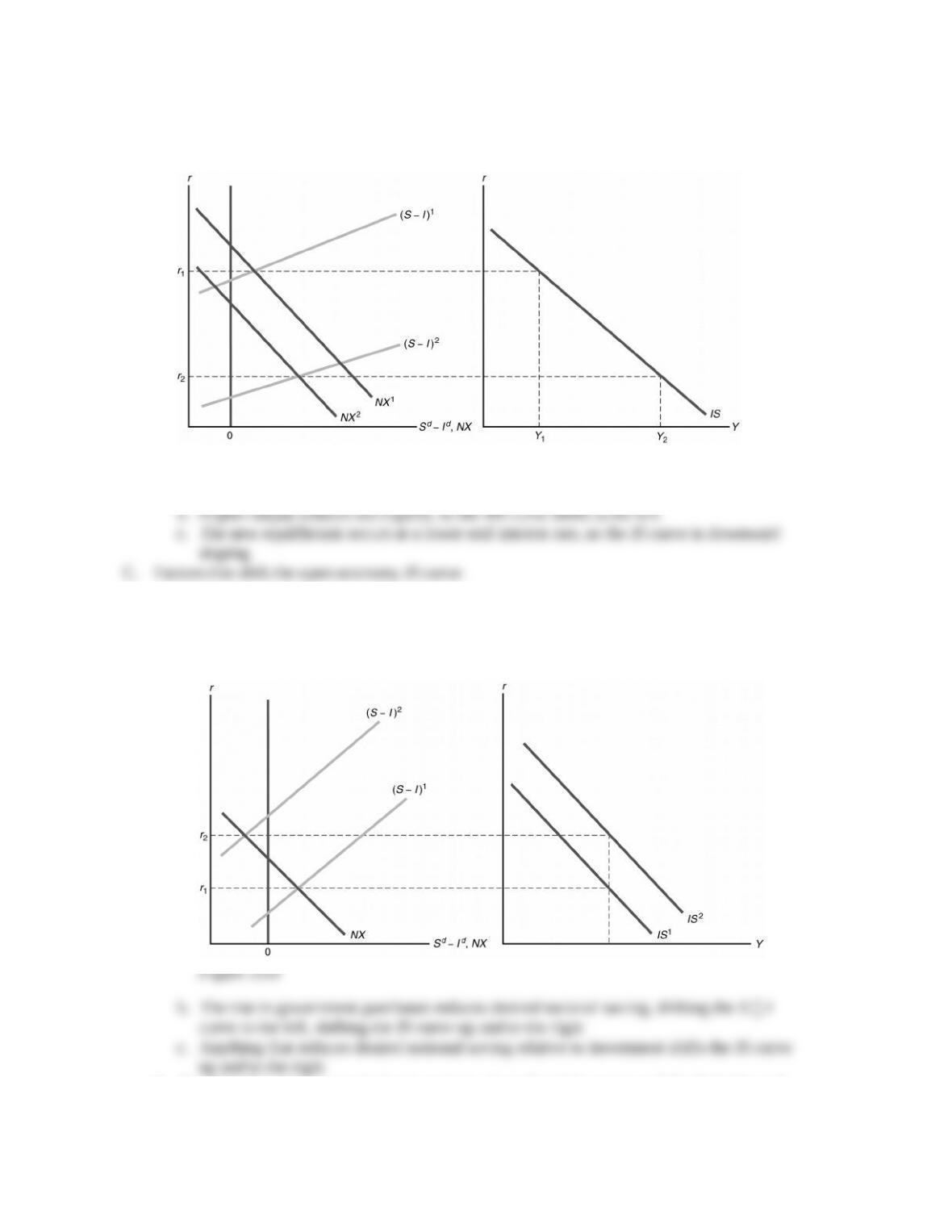

1. To examine the relationship between the nominal exchange rate and the real exchange rate,

think first about a simple case in which all countries produce the same goods, which are

freely traded

a. If there were no transportation costs, the real exchange rate would have to be e 1, or

else everyone would buy goods where they were cheaper

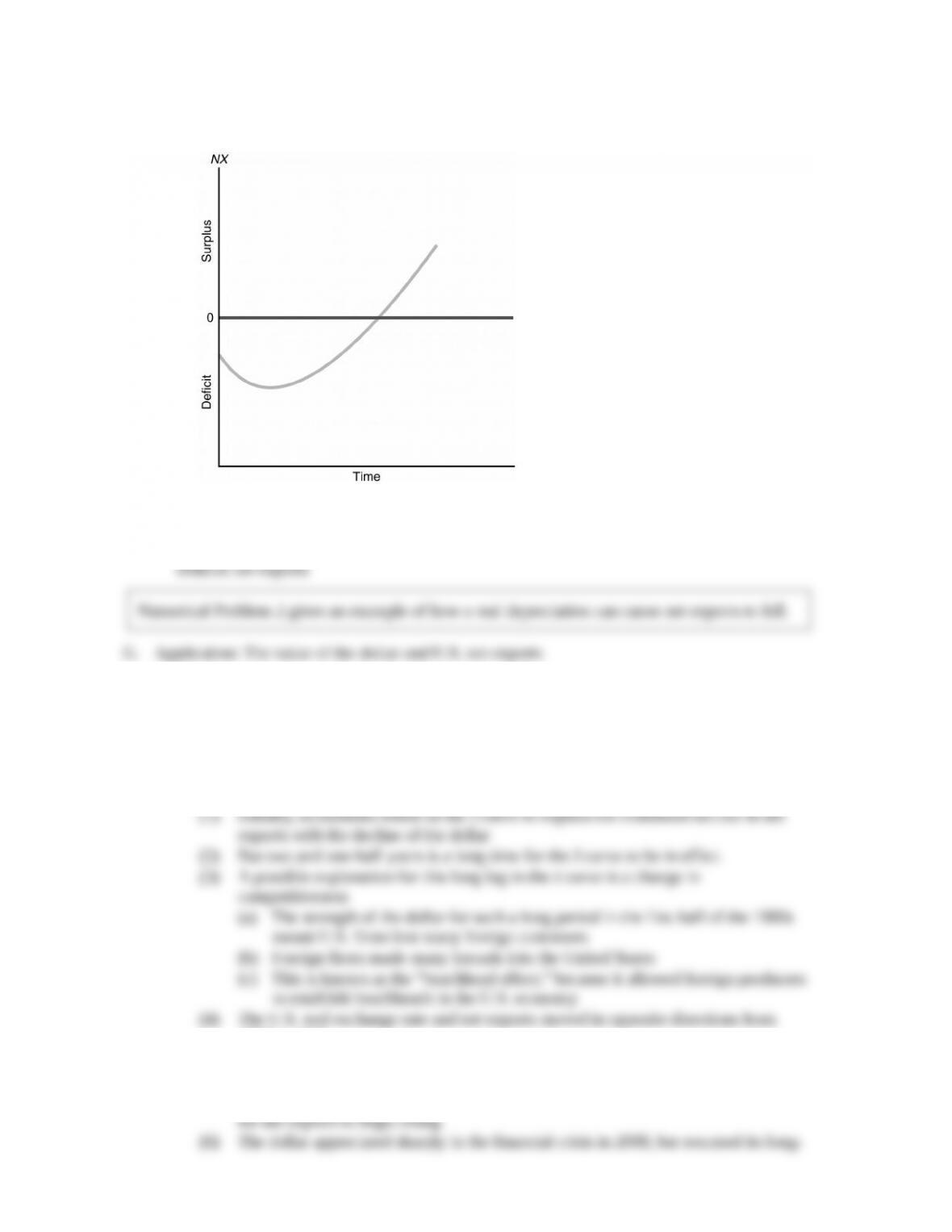

2. When PPP doesn’t hold, using Eq. (13.1), we can decompose changes in the real exchange