1. In the classical model, money is neutral since prices adjust quickly

a. In this case, the only relevant supply curve is the long-run aggregate supply curve

2. But if producers misperceive the aggregate price level, then the relevant aggregate supply

curve in the short run isn’t vertical

a. This happens because producers have imperfect information about the general price level

b. As a result, they misinterpret changes in the general price level as changes in relative prices

1. This makes the AS curve slope upward

2. Example: A bakery that makes bread

a. The price of bread is the baker’s nominal wage; the price of bread relative to the general

price level is the baker’s real wage

b. If the relative price of bread rises, the baker may work more and produce more bread

3. Generalizing this example, if everyone expects prices to increase 5% but they actually

increase 8%, they’ll work more

4. So an increase in the price level that is higher than expected induces people to work more

and thus increases the economy’s output

5. Similarly, an increase in the price level that is lower than expected reduces output

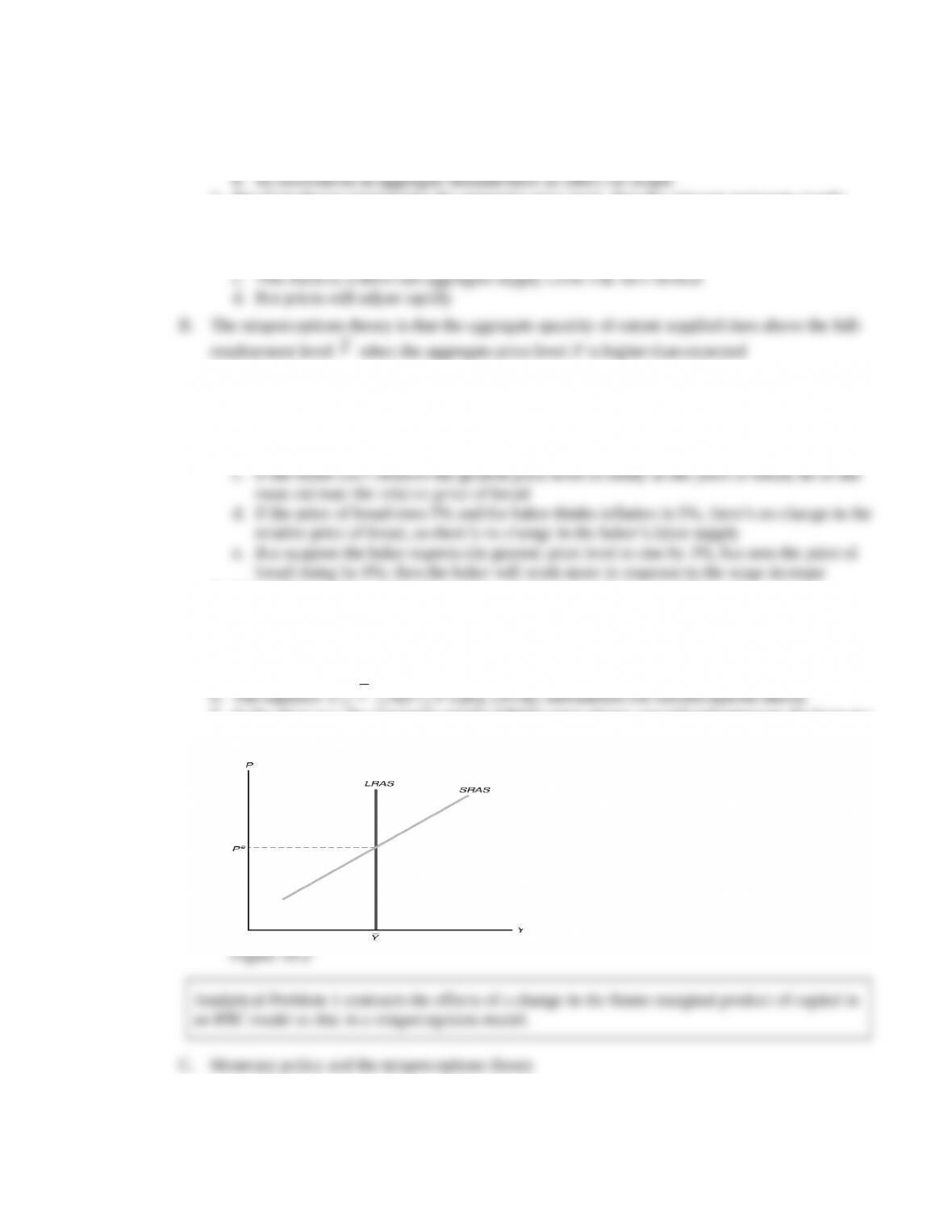

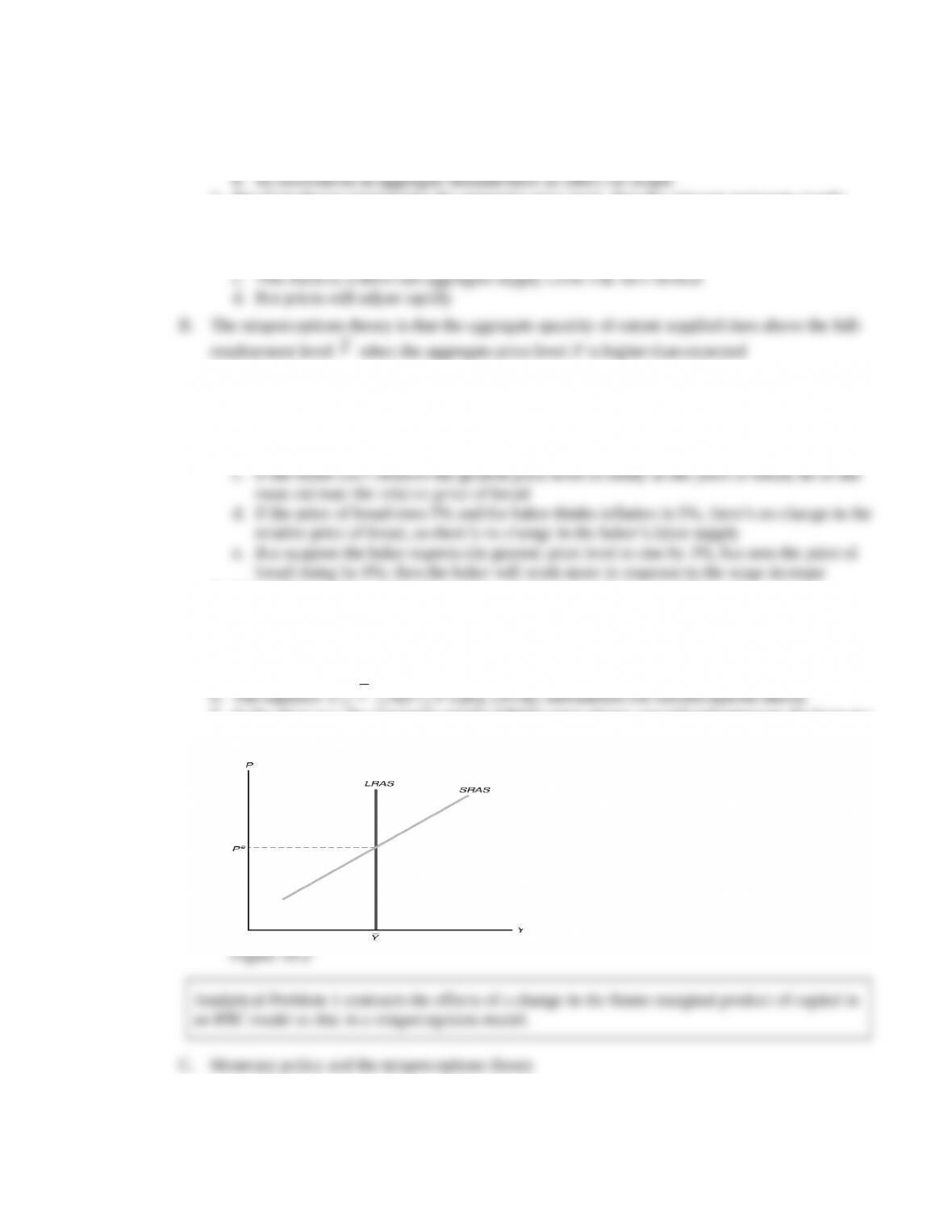

7. In the short run, the aggregate supply (SRAS) curve slopes upward and intersects the long-run

aggregate supply (LRAS) curve at P Pe (Figure 10.2; like text Figure 10.7)

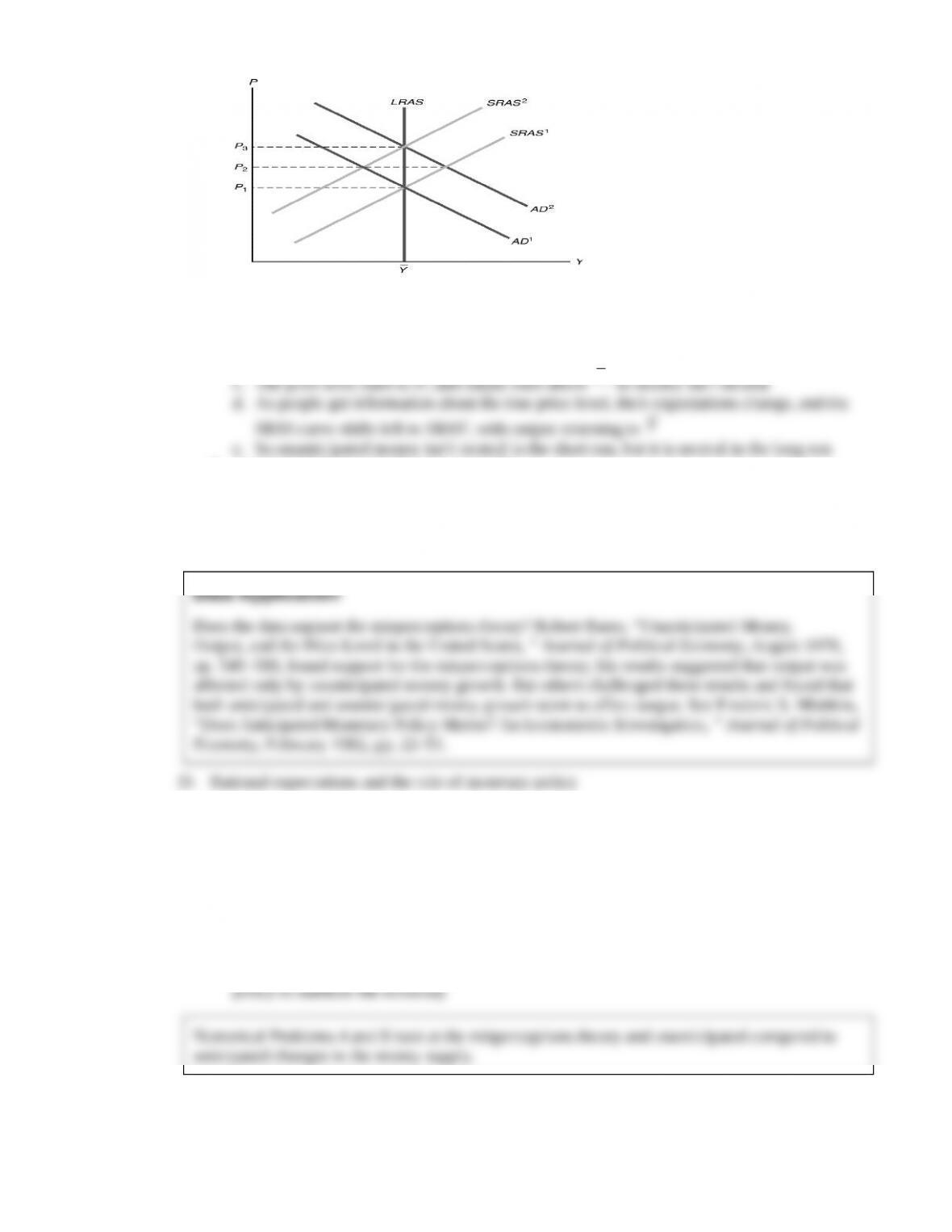

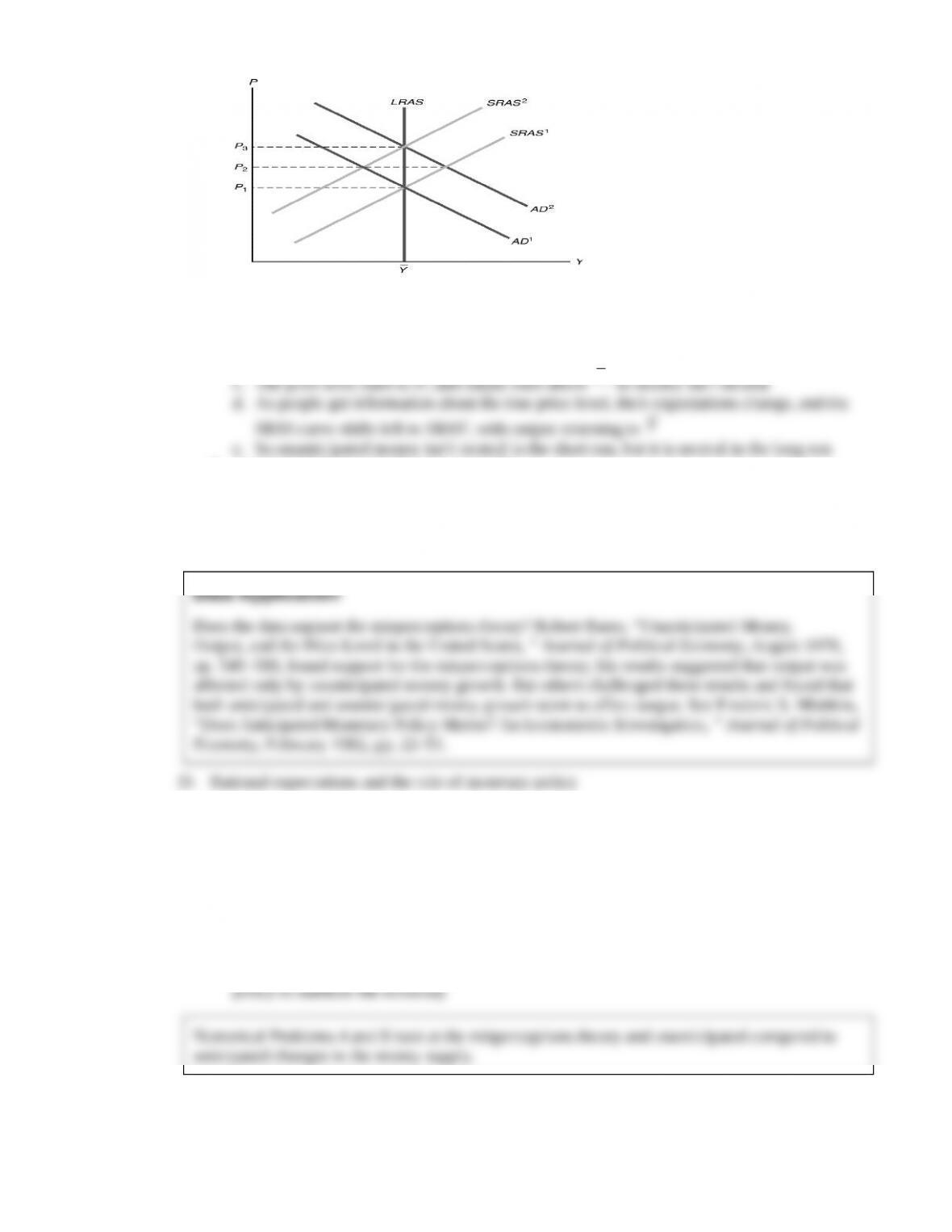

1. Because of misperceptions, unanticipated monetary policy has real effects; but anticipated

monetary policy has no real effects because there are no misperceptions

2. Unanticipated changes in the money supply (Figure 10.3; like text Figure 10.8)