1. Classical economists oppose attempts to dampen the cycle, since prices and wages adjust

quickly to restore equilibrium

2. Besides, fiscal policy increases output by making workers worse off, since they face higher

taxes

3. Instead, government spending should be determined by cost-benefit analysis

4. Also, there may be lags in enacting the correct policy and in implementing it

a. So choosing the right policy today depends on where you think the economy will be in

5. It’s also not clear how much to change fiscal policy to get the desired effect on employment

and output

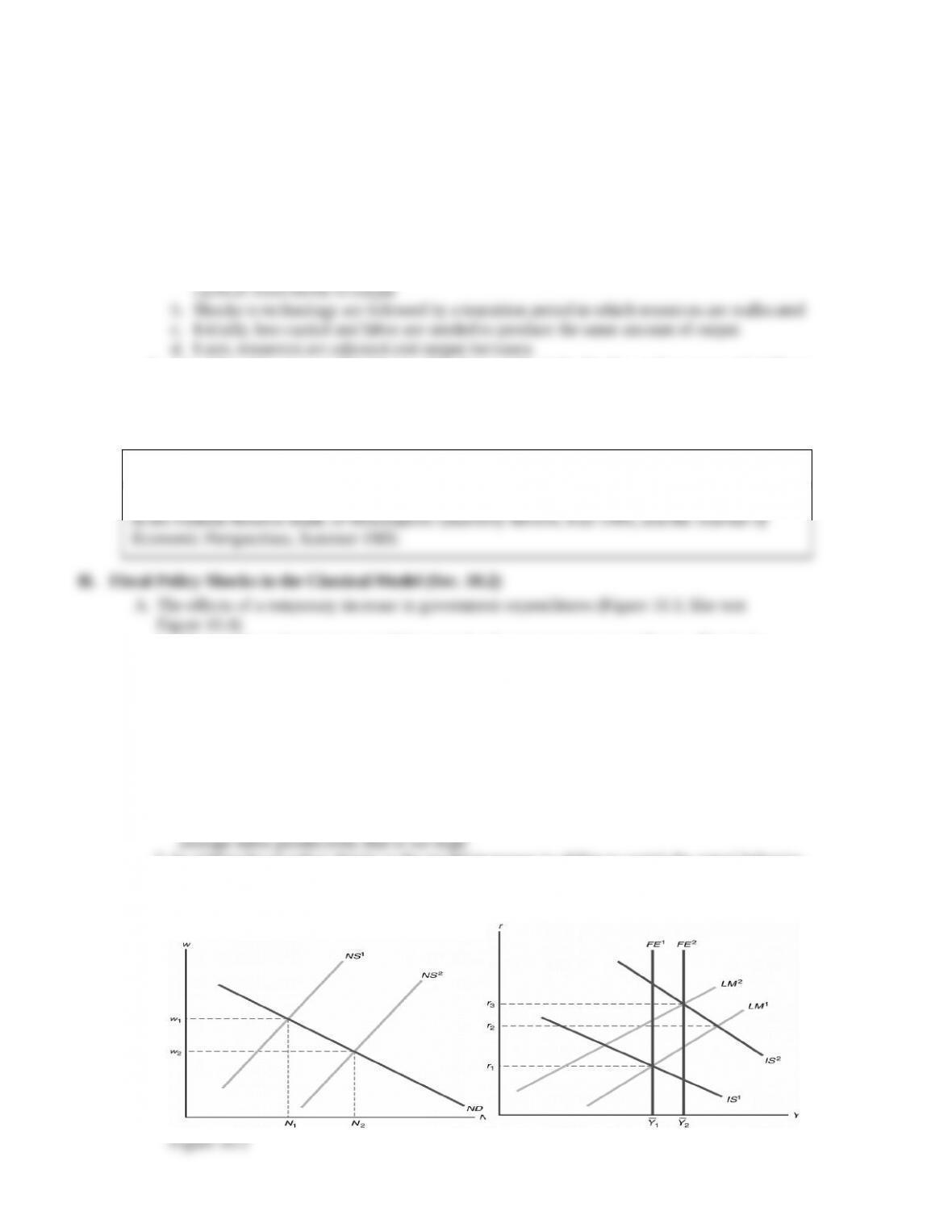

III. Unemployment in the Classical Model (Sec. 10.3)

A. In the classical model there is no unemployment; people who aren’t working are voluntarily

1. Workers and jobs have different requirements, so there is a matching problem

2. It takes time to match workers to jobs, so there is always some unemployment

3. Unemployment rises in recessions because productivity shocks cause increased mismatches

between workers and jobs

4. A shock that increases mismatching raises frictional unemployment and may also cause

structural unemployment if the types of skills needed by employers change

5. So the shock causes the natural rate of unemployment to rise; there’s still no cyclical

unemployment in the classical model

Theoretical Application

A nice discussion of the classical view of unemployment is by Robert E. Lucas, Jr., Models of

Business Cycles, Chapter V, New York: Basil Blackwell, 1987.

1. Many workers are laid off temporarily; there’s no mismatch, just a change in the timing of

work

2. If recessions were times of increased mismatch, there should be a rise in help-wanted ads in

recessions, but in fact they fall