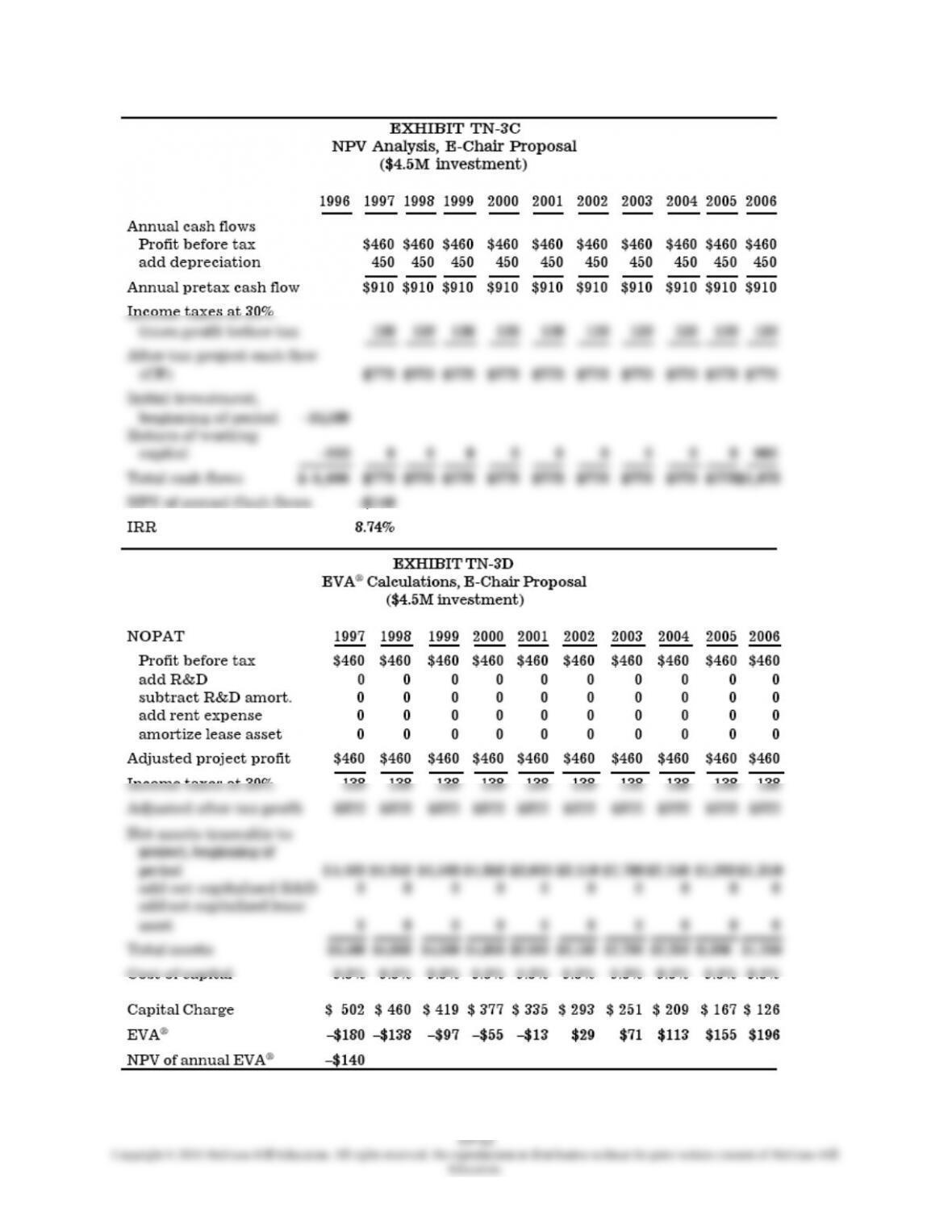

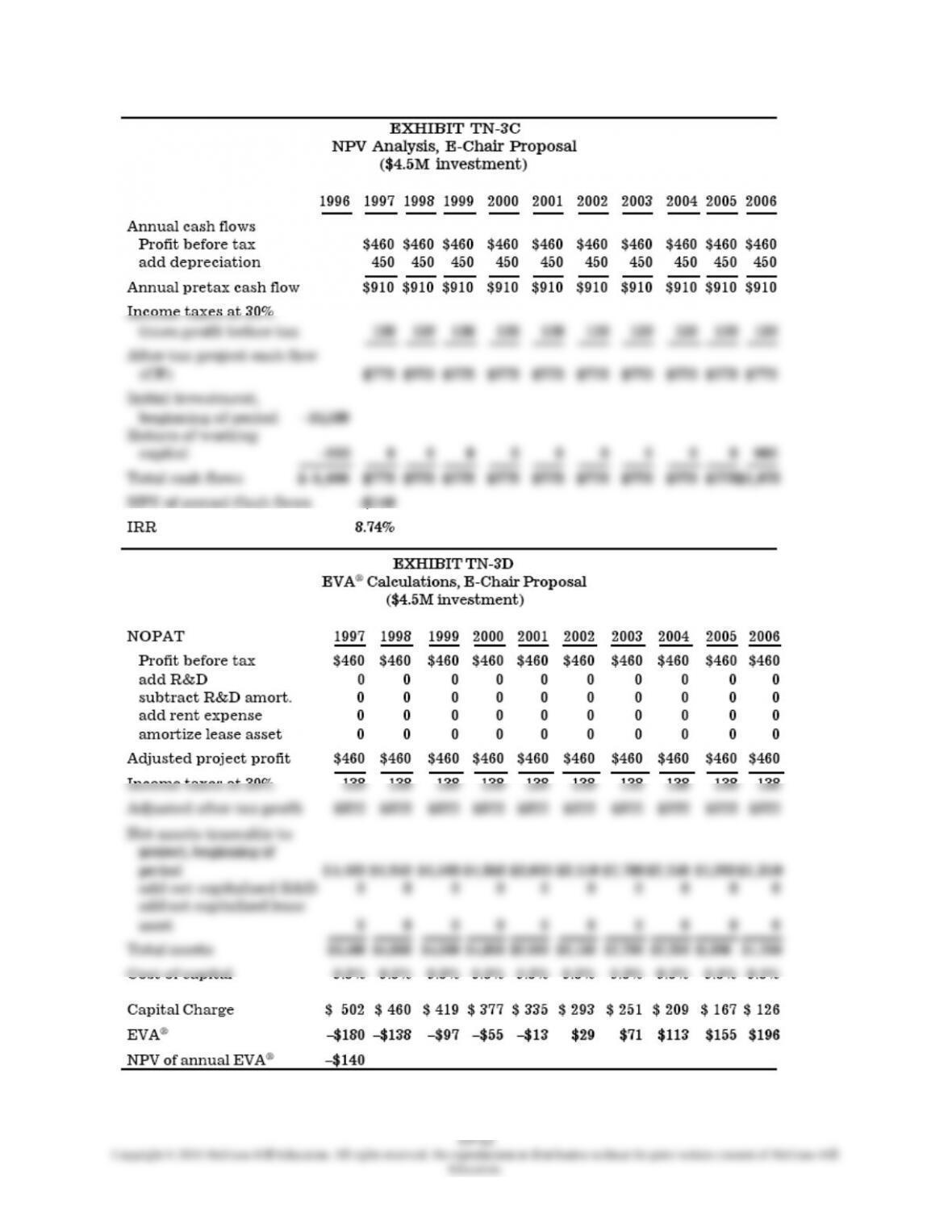

3. EVA® should mitigate but not eliminate incentives to emphasize short-run performance. Annual EVA®

is still based on a one-period historical model. However, accounting “distortions” such as the requirement

to expense R&D are “corrected” in calculating EVA®. In practice, EVA® compensation plans are often

implemented as rolling three-year targets in order to lengthen the managers’ planning horizon.

For example, without lengthening the time horizon, a proposal might be rejected because it produces

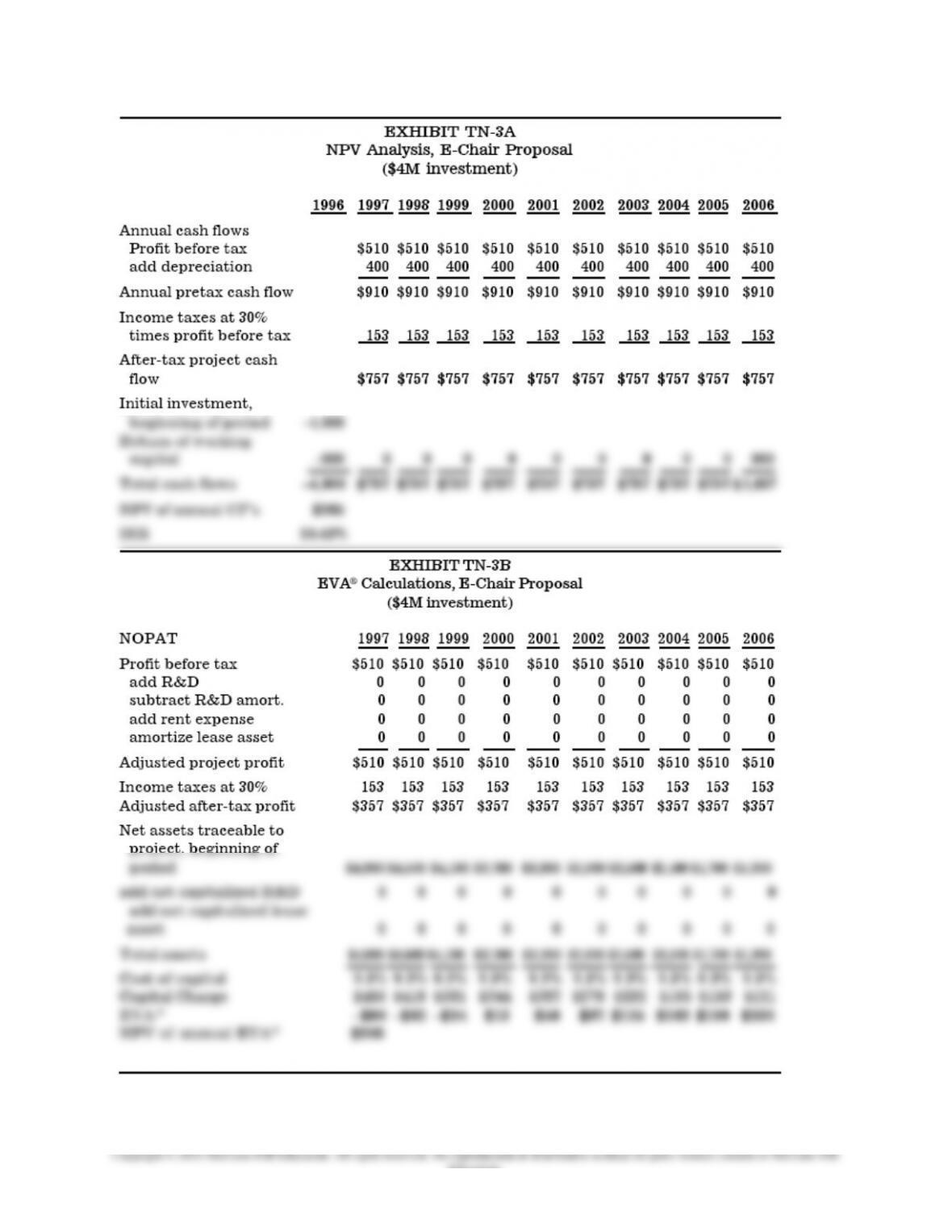

before explicitly incorporating the measure into management incentive compensation plans. (Of course it

is possible that all the accolades for EVA® are due to self-selection, i.e., of those firms that consider

EVA®, the only ones that adopt it are successful firms that can “afford” to take a charge for equity

capital.) Many firms now include disclosure about their use of an EVA® performance measure; however,

they do not report actual EVA® performance.

Journal of Applied Corporate Finance discusses these costs. Zimmerman (1997) gives the example of a

firm that capitalizes a large amount of R&D expense, leading to high and growing EVA® and high

EVA®-based bonuses. In his example, the stock price is also rising because the market looks beyond the

GAAP numbers to the EVA® results, believing the R&D will pay off. Unfortunately in this example a

new scientific discovery destroys the usefulness of the firm’s R&D expenditures, leading to a sharp drop

in the stock price. The R&D must be written off, leading to a sharp drop in EVA®. (No adjustment is

needed for GAAP earnings since R&D is already expensed.) In retrospect, the managers received large

EVA®-based bonuses that now appear unwarranted. A potential shareholder lawsuit could result because

the large EVA®-based bonuses may appear self-serving, given that GAAP earnings were much lower all

along. Some CPA firms might relish the opportunity to work with firms that adopt EVA®. Several of the

large accounting firms currently market versions of similar shareholder value measures.

Supplemental Questions

5. Note that this question does not directly deal with the merits of EVA®. Instead it addresses the more

general topic of accounting-based vs. stock-based compensation. No, it is probably a good idea to

continue to tie at least some of the managers’ incentive compensation to accounting (or EVA®)

performance even after the stock is publicly traded (Lambert 1993, 101). A reason to have an incentive