Chapter 14 - Operational Performance Measurement: Sales, Direct Cost Variances, and the Role of Nonfinancial

Performance Indicators

maximum efficiency in every aspect of the operation and is not easily attainable. A currently attainable

standard sets the performance criterion at a level that workers with proper training and experience can

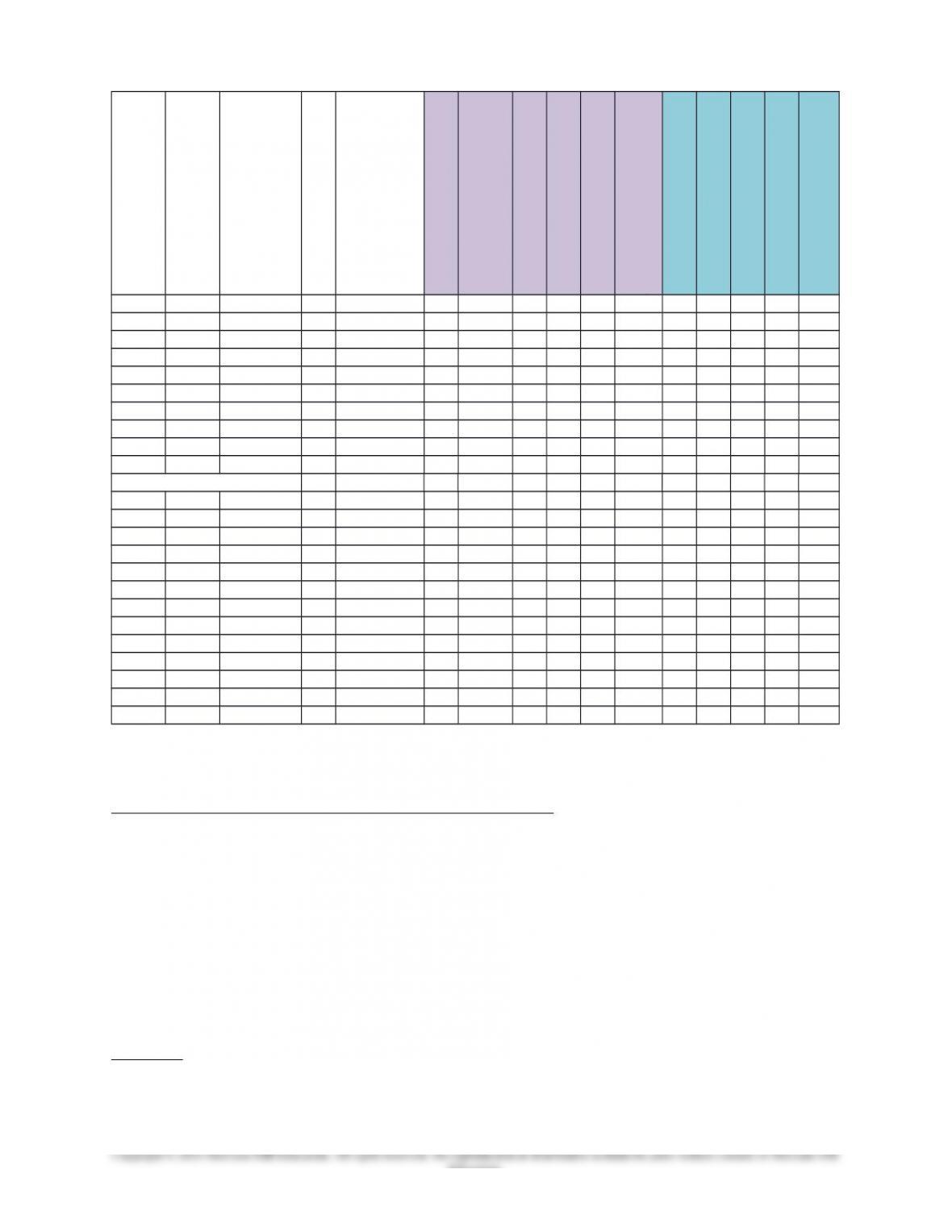

attain most of the time without extraordinary effort. An example of a standard cost sheet is provided in

Exhibit 14.5.

A firm can use activity analysis, historical data, benchmarks, market expectation, target cost, or strategic

decision to set the standards. Setting the standard using activity analyses requires analyses of all activities

required to complete a job, project, or operation. It is often expensive and time-consuming.

Benchmarking is the process of measuring products, services, and activities against the best performance.

Using benchmarking to set standard has the advantage of using the best performance anywhere as the

standard and help the firm to maintain its competitive edge. The target cost for a product is the cost that

will yield the desired profit margin, given the market price of the product.

The availability of standard cost (and revenue) information enables the managerial accountant to

breakdown the total flexible budget variance into its components: a total selling price variance and a

flexible budget variance for each cost, variable and fixed. The fixed cost variances are called “spending

variances.”

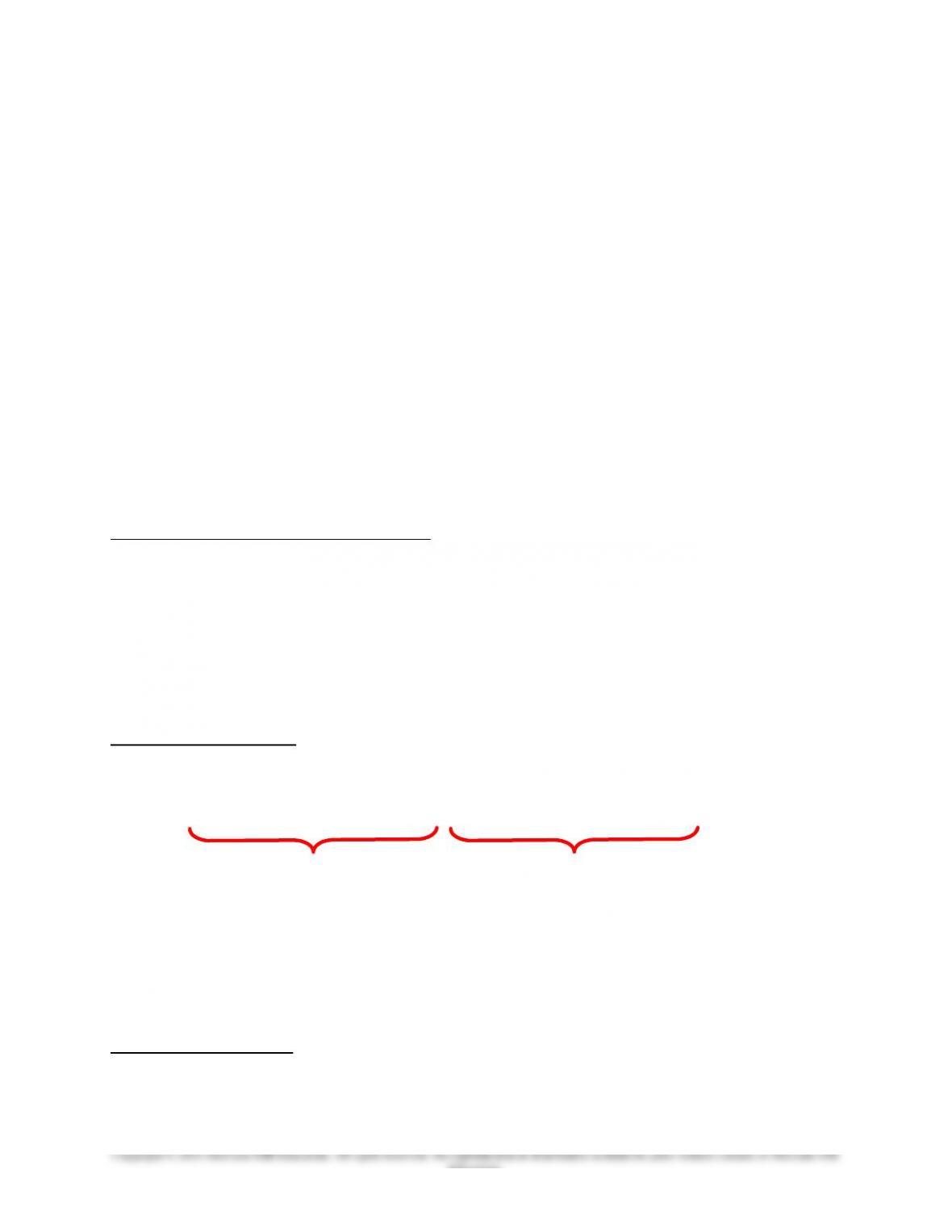

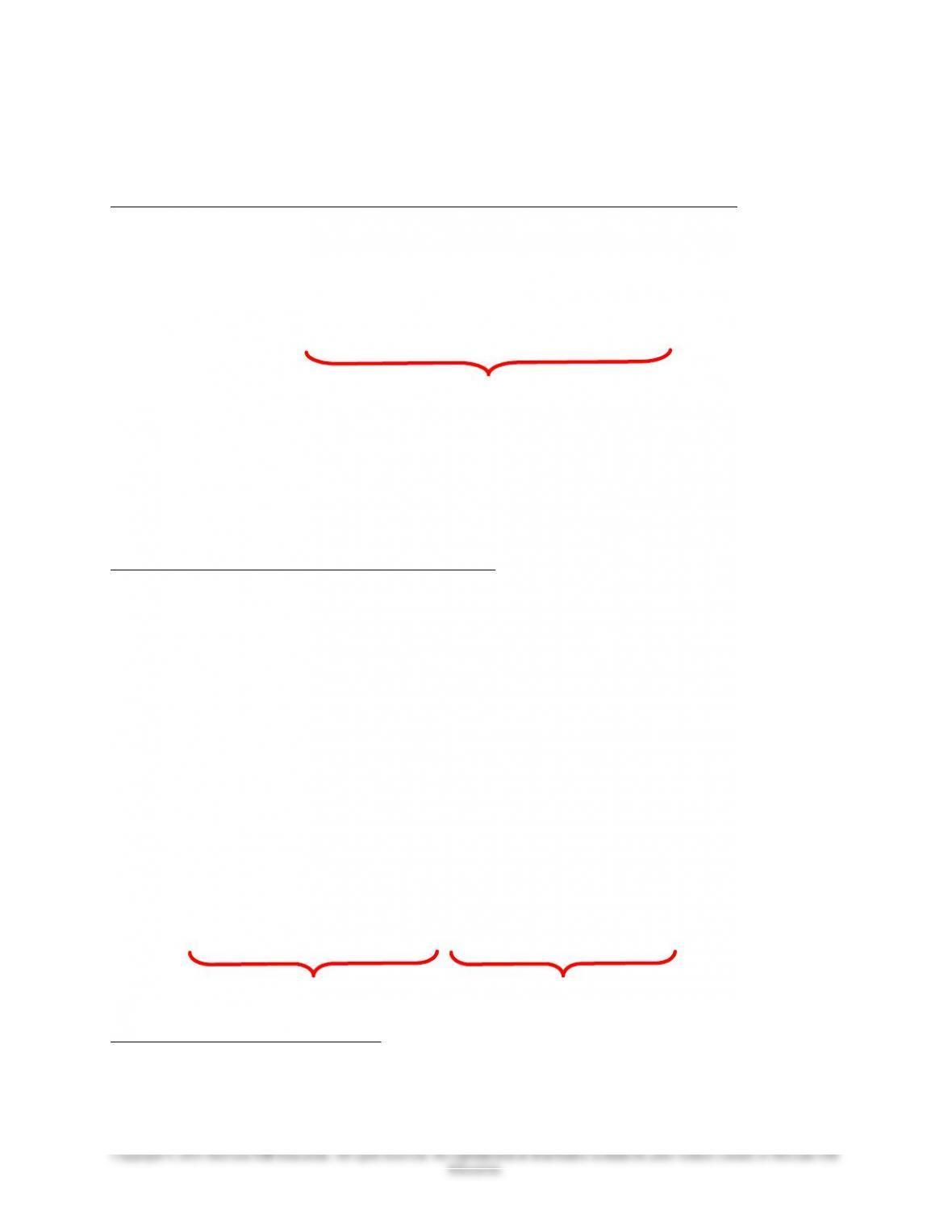

Further decomposition of the fixed cost variances would be to assign each spending variance to a

responsibility center (product, department, geographic region, manager, etc.). The series of variable cost

flexible budget variances can each be broken down into price (p) and quantity/efficiency (q) components,

as discussed below for direct labor and direct materials.

Direct Cost Variances: Materials and Labor

A manufacturing firm usually has a standard cost sheet that details the standard quantity and standard cost

for all the significant cost elements of the operations. Typical standards include standards for direct

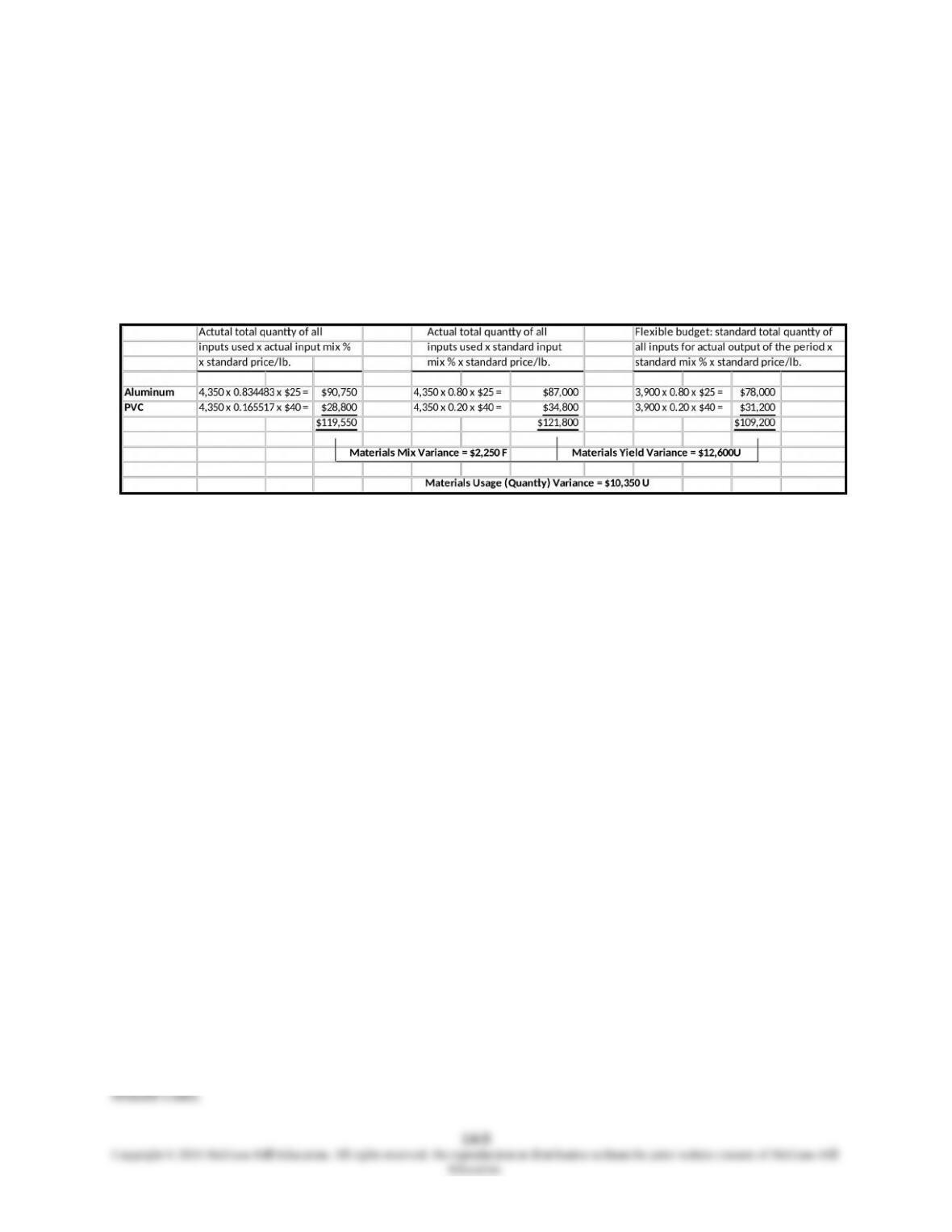

materials (DM) and direct labor (DL). A DM flexible budget variance can be separated, for each material,

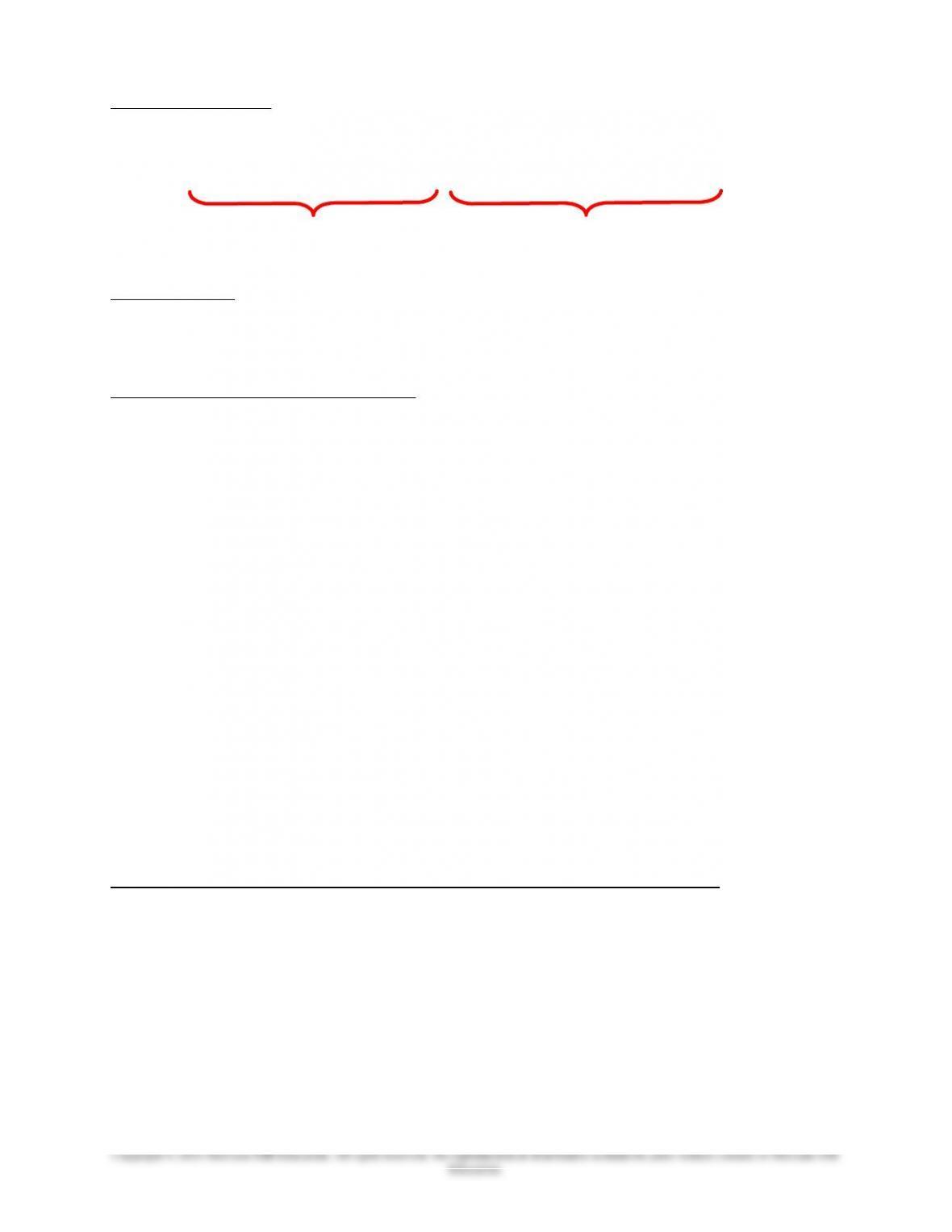

into a DM price and a DM usage variance. A DL flexible budget variance can be further divided into DL

rate and DL efficiency variances, by developing a second flexible budget, that is, one based on actual

resource inputs (actual units of material or actual labor hours worked). A diagrammatic representation of

the variance decomposition process for DM and DL costs follows (see Exhibit 14.7, Exhibit 14.8,

Exhibit 14.9, and Exhibit 14.10):

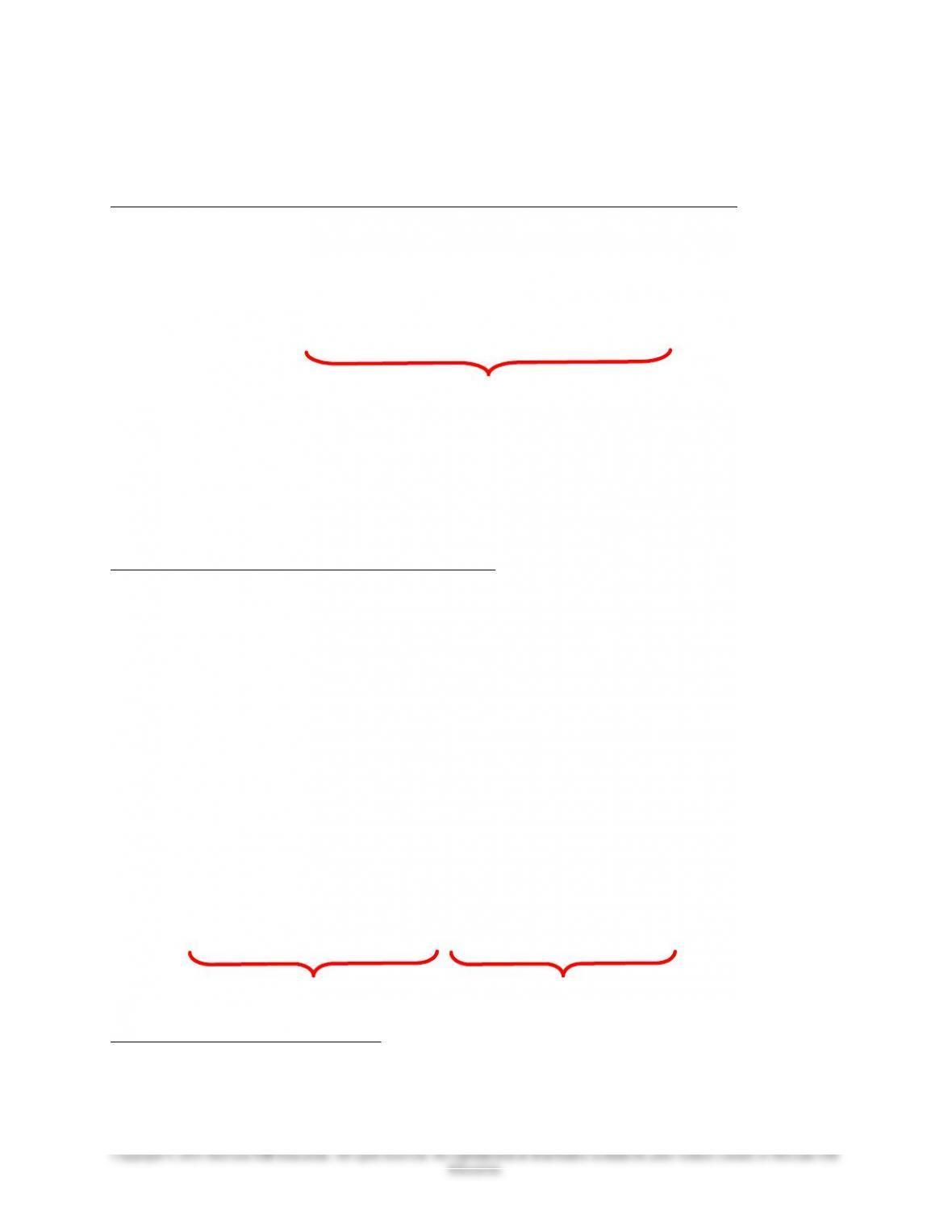

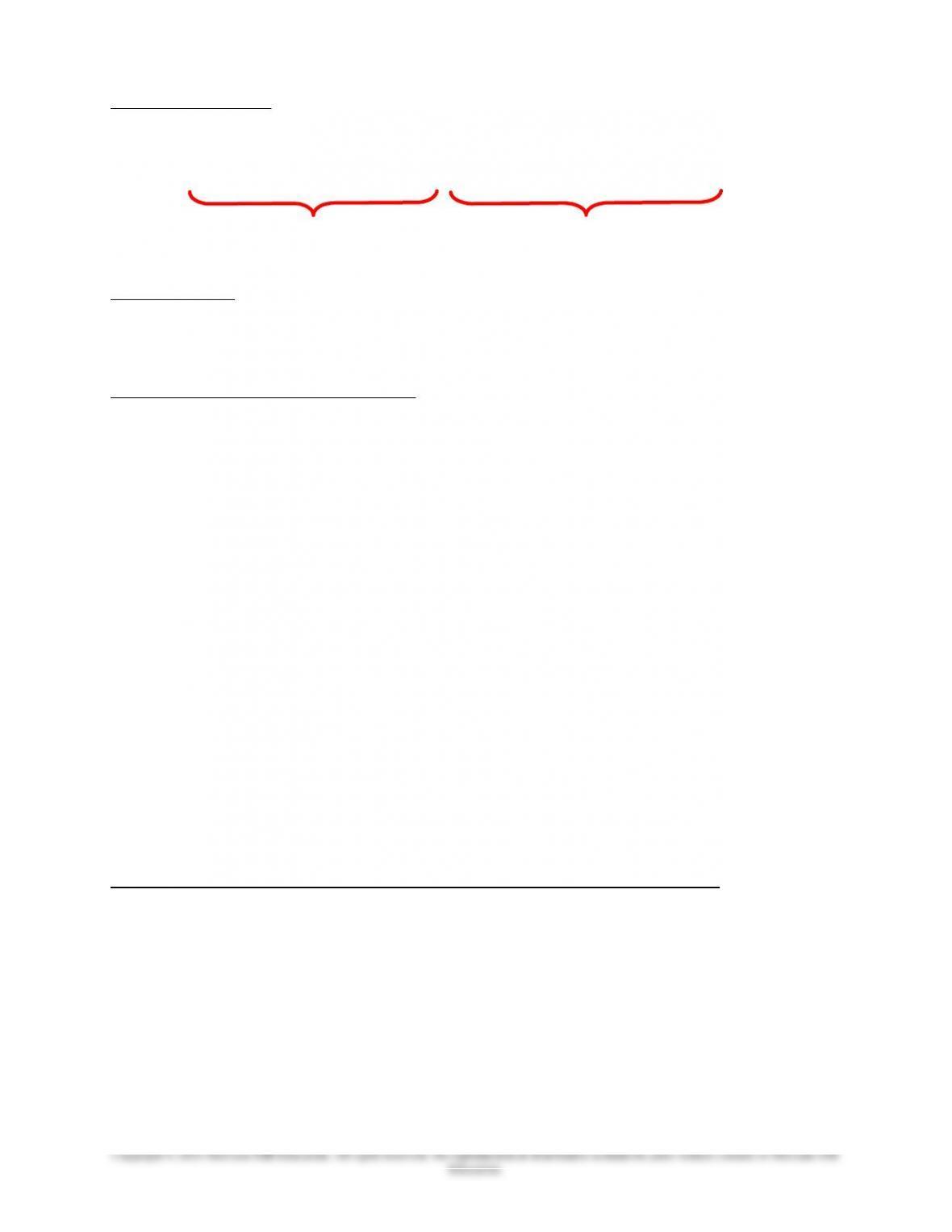

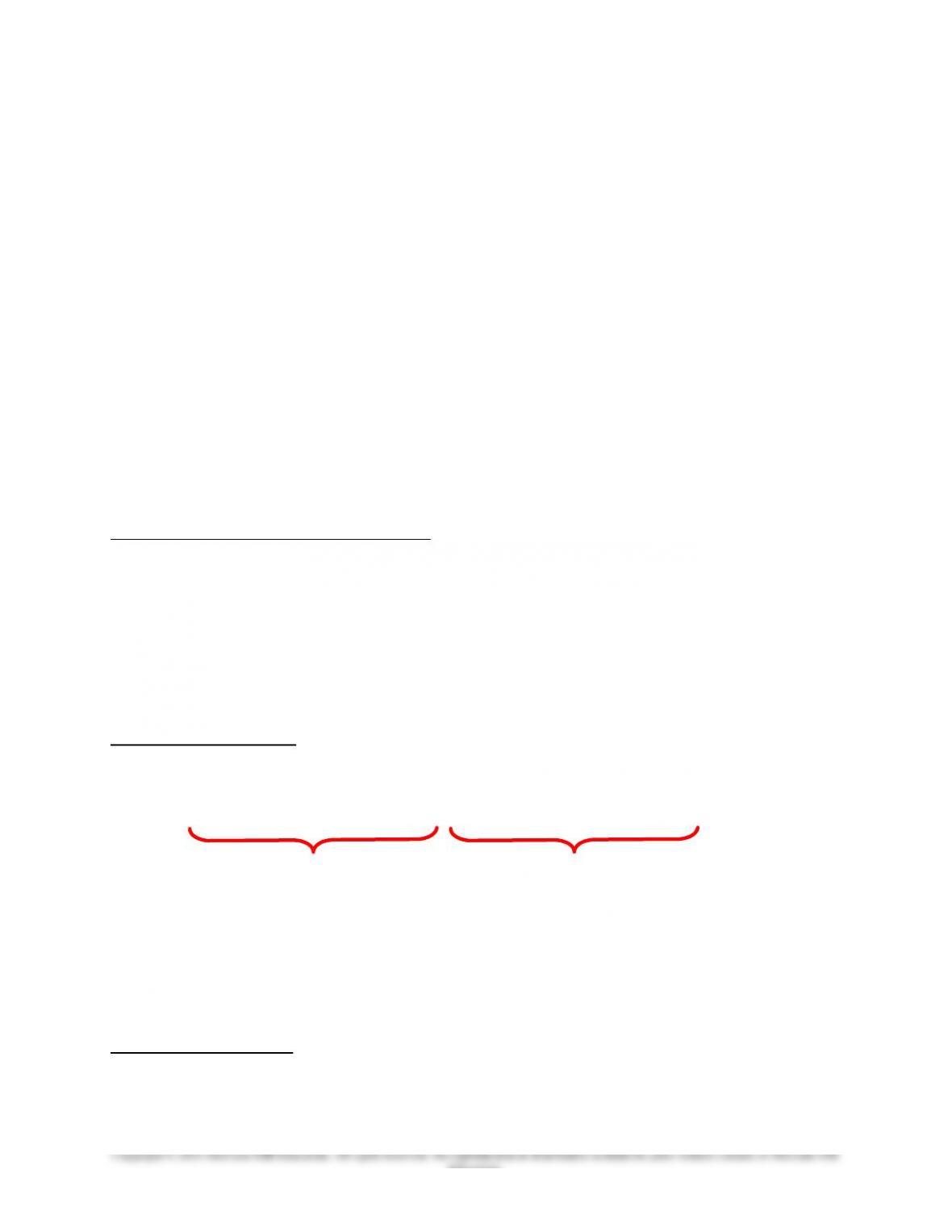

Direct Materials Variances

FB Based on Output

Actual FB Based on Inputs (Standard Quantity of DM Allowed for

Cost Incurred (Quantity Used × Standard Cost) Output Achieved × Standard Cost)

(AQ × AP) (AQ × SP) (SQ × SP)

Price Variance Usage Variance1

NOTE: If the company calculates the DM price variance at point of purchase, this variance is referred to

as the direct materials purchase price variance. When this is the case, then AQ in the price variance

formula refers to the Actual Quantity purchased. For the usage (efficiency) variance calculation, AQ

stands for Actual Quantity issued to (consumed in) production.

If the price variance for materials is not calculated until the materials are issued to production, then AQ in

the above diagram stands in all cases for Actual Quantity used (issued to production) during the period.

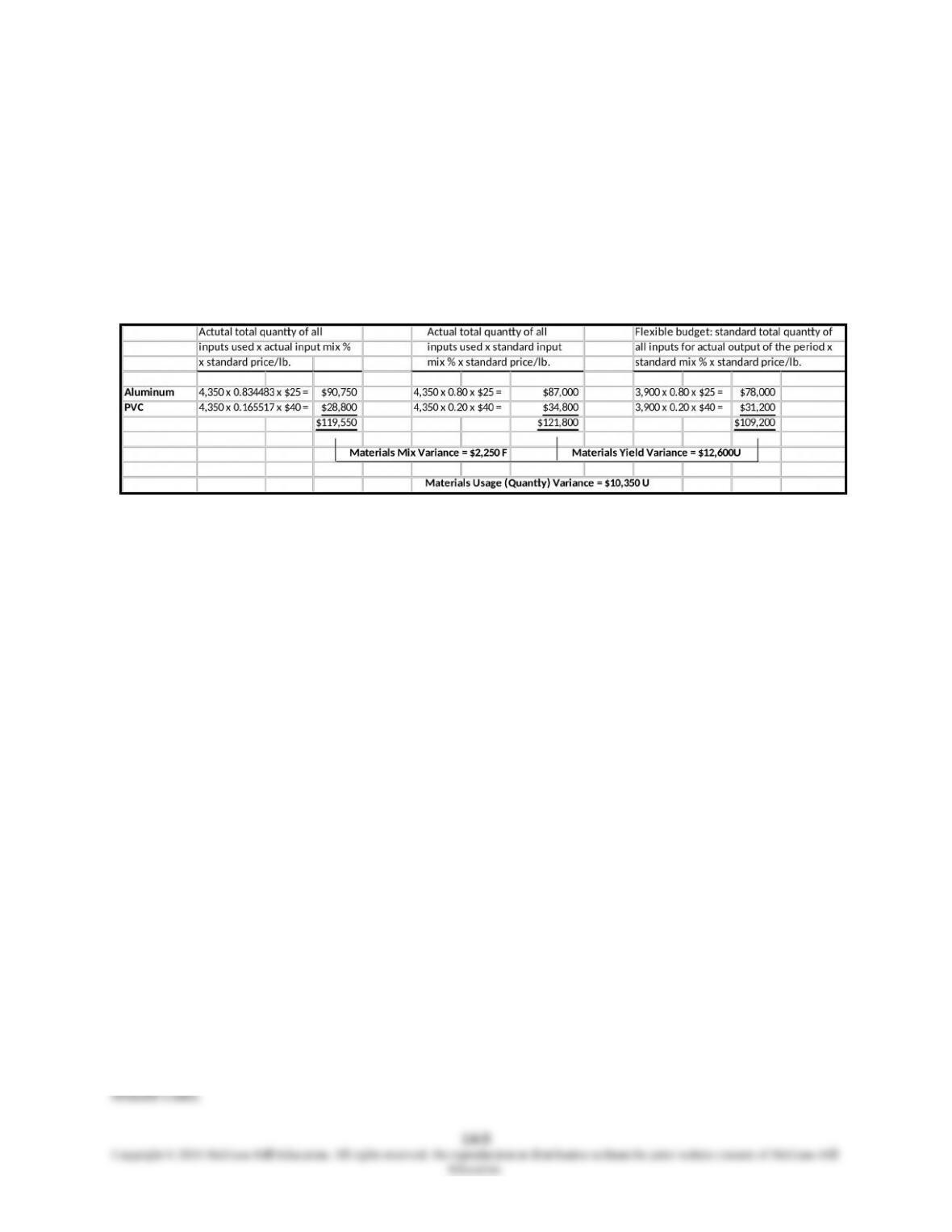

1 If there are multiple labor classes (categories) that are substitutable, then it is possible to break the direct labor

efficiency (quantity) variance into a direct labor mix variance and a direct labor mix variance. As noted below, if

there are multiple direct materials, and these materials are substitutable, then the direct materials quantity variance

can similarly be broken down into a mix variance and a yield variance.

14-5

Education.