Chapter 9 NAME

Buying and Selling

Introduction. In previous chapters, we studied the behavior of con-

sumers who start out without owning any goods, but who had some money

with which to buy goods. In this chapter, the consumer has an initial en-

dowment, which is the bundle of goods the consumer owns before any

trades are made. A consumer can trade away from his initial endowment

by selling one good and buying the other.

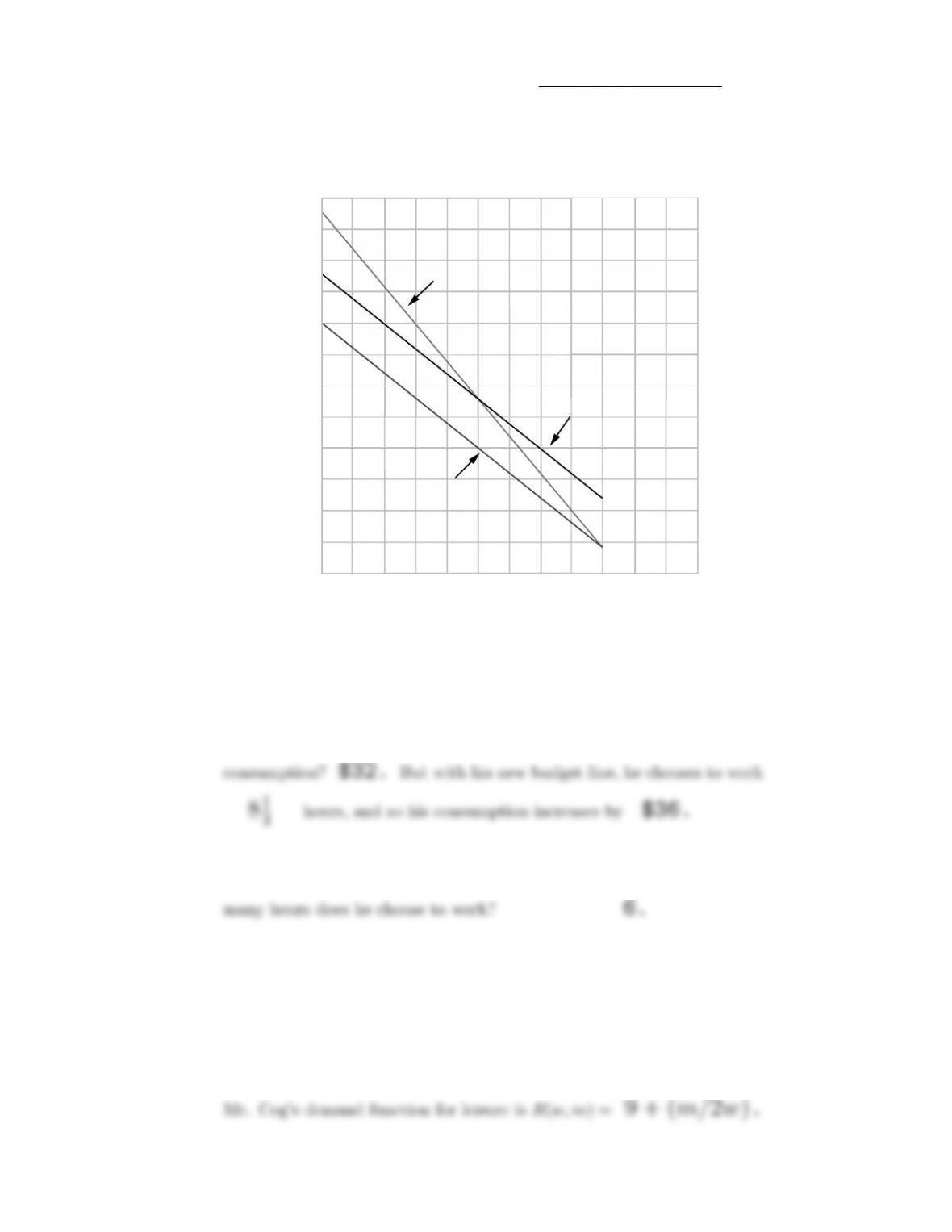

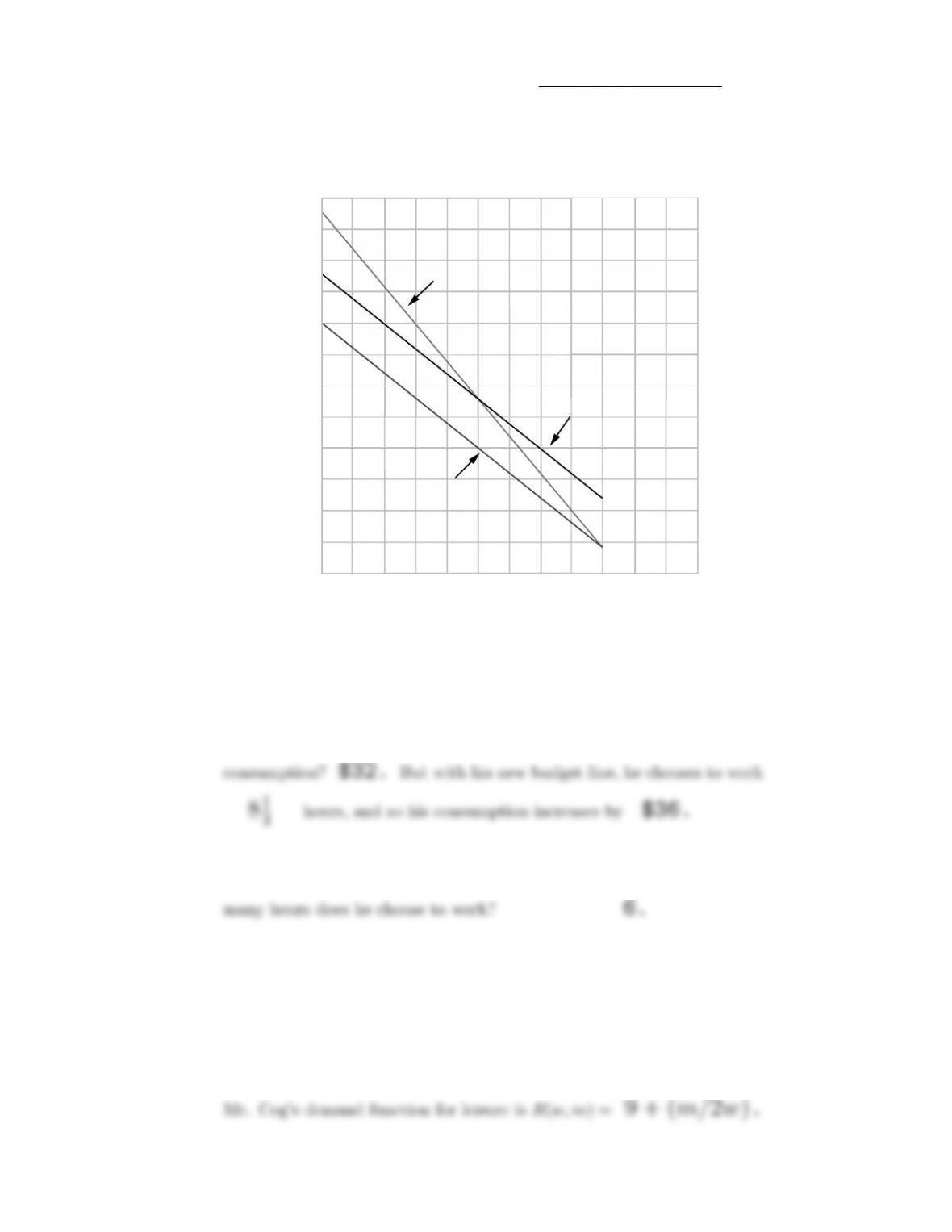

The techniques that you have already learned will serve you well here.

To find out how much a consumer demands at given prices, you find his

budget line and then find a point of tangency between his budget line and

an indifference curve. To determine a budget line for a consumer who

is trading from an initial endowment and who has no source of income

other than his initial endowment, notice two things. First, the initial

endowment must lie on the consumer’s budget line. This is true because,

no matter what the prices are, the consumer can always afford his initial

endowment. Second, if the prices are p1and p2, the slope of the budget

line must be −p1/p2.This is true, since for every unit of good 1 the

consumer gives up, he can get exactly p1/p2units of good 2. Therefore

if you know the prices and you know the consumer’s initial endowment,

then you can always write an equation for the consumer’s budget line.

After all, if you know one point on a line and you know its slope, you

can either draw the line or write down its equation. Once you have the

budget equation, you can find the bundle the consumer chooses, using the

same methods you learned in Chapter 5.

Example: A peasant consumes only rice and fish. He grows some rice and

some fish, but not necessarily in the same proportion in which he wants

to consume them. Suppose that if he makes no trades, he will have 20

units of rice and 5 units of fish. The price of rice is 1 yuan per unit, and

the price of fish is 2 yuan per unit. The value of the peasant’s endowment

is (1 ×20) + (2 ×5) = 30. Therefore the peasant can consume any bundle

(R, F ) such that (1 ×R)+(2×F) = 30.

Perhaps the most interesting application of trading from an initial

endowment is the theory of labor supply. To study labor supply, we

consider the behavior of a consumer who is choosing between leisure and

other goods. The only thing that is at all new or “tricky” is finding

the appropriate budget constraint for the problem at hand. To study

labor supply, we think of the consumer as having an initial endowment of

leisure, some of which he may trade away for goods.

In most applications we set the price of “other goods” at 1. The

wage rate is the price of leisure. The role that is played by income in

the ordinary consumer-good model is now played by “full income.” A

worker’s full income is the income she would have if she chose to take no

leisure.