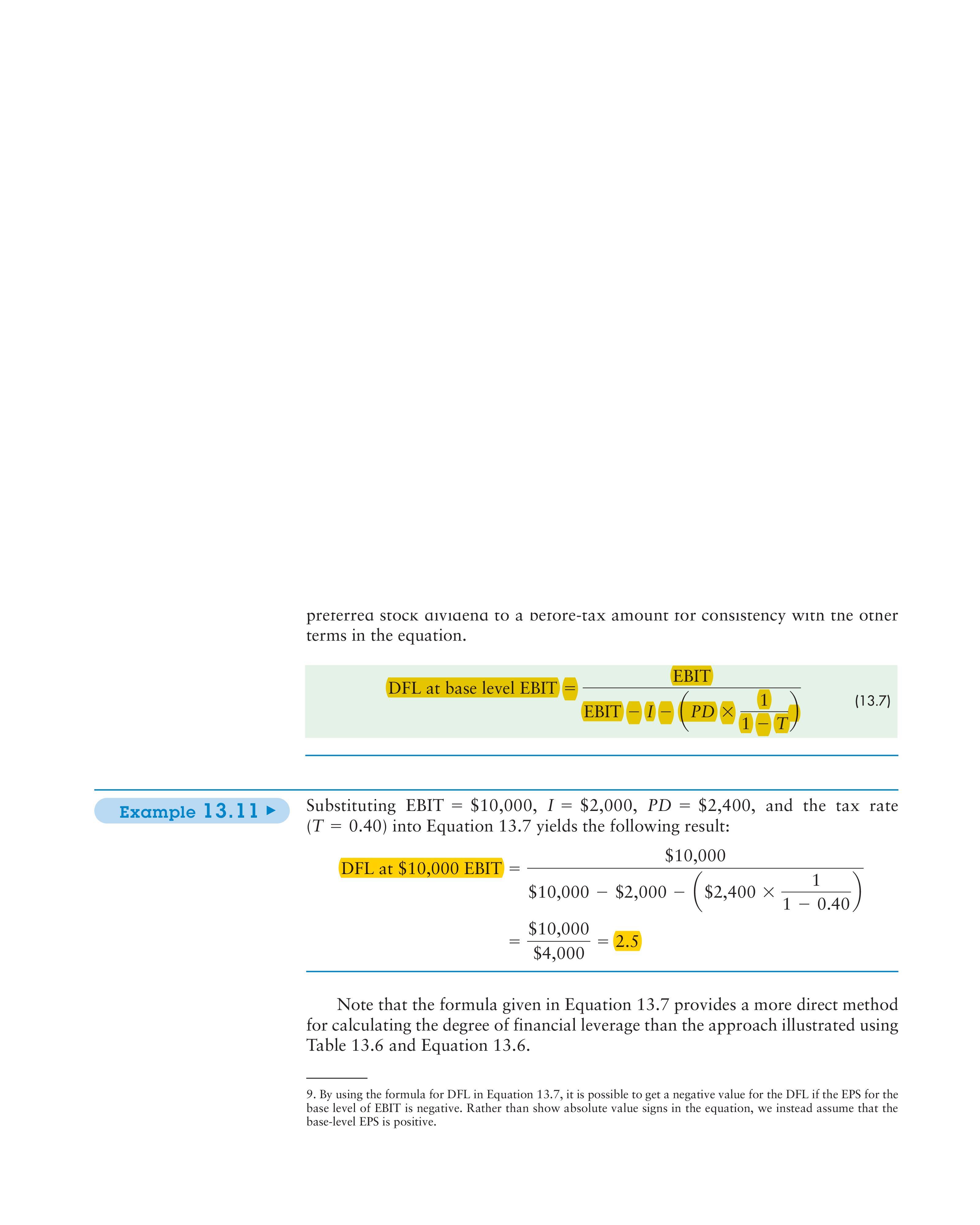

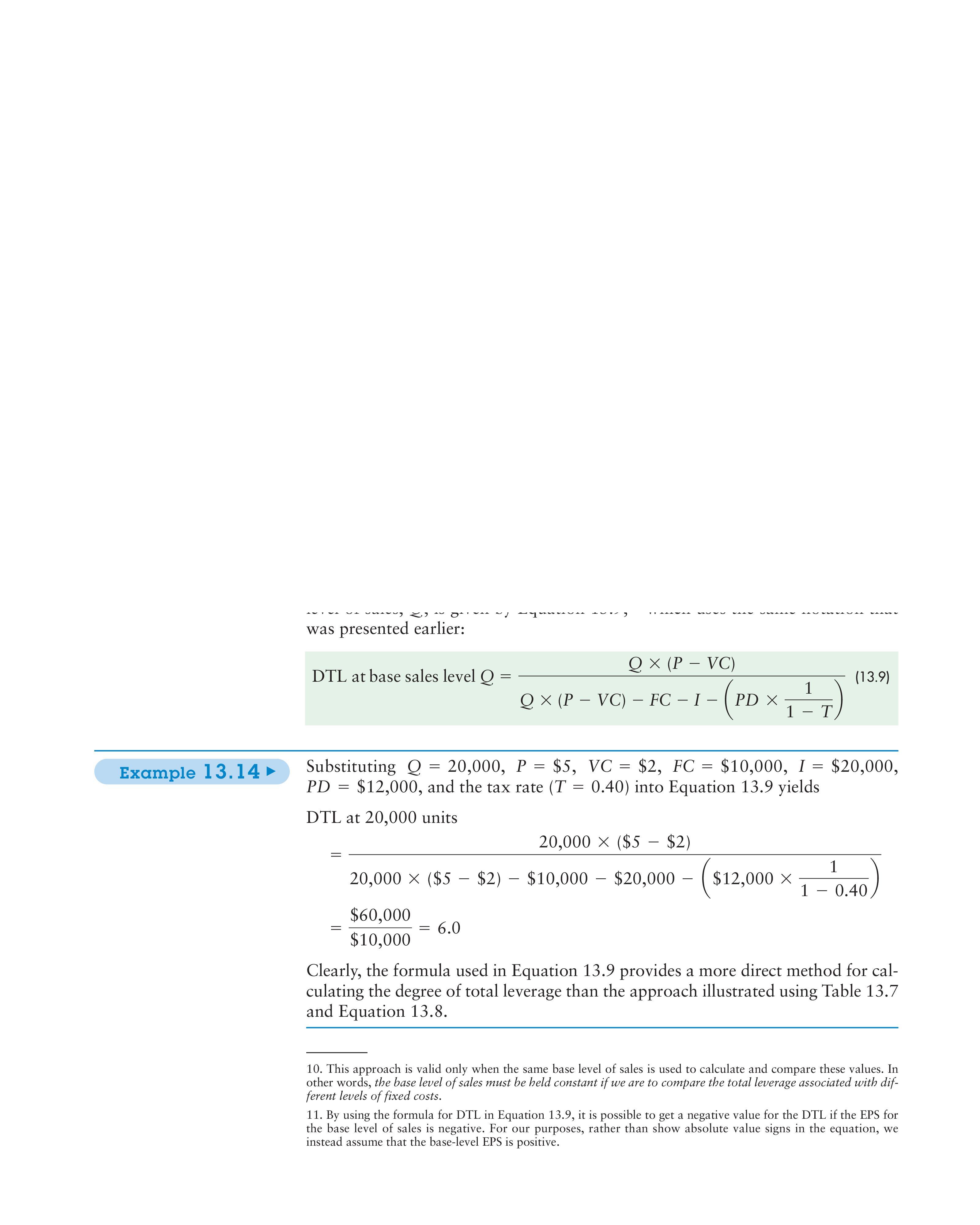

A more direct formula for calculating the degree of operating leverage at a

base sales level, Q, is shown in Equation 13.5.5

(13.5)

Substituting , and into Equation

13.5 yields the following result:

The use of the formula results in the same value for DOL (2.0) as that found by

using Table 13.4 and Equation 13.4.6

See the Focus on Practice box for a discussion of operating leverage at software

maker Adobe.

DOL at 1,000 units =1,000 *($10 -$5)

1,000 *($10 -$5) -$2,500 =$5,000

$2,500 =2.0

FC =$2,500Q=1,000, P=$10, VC =$5

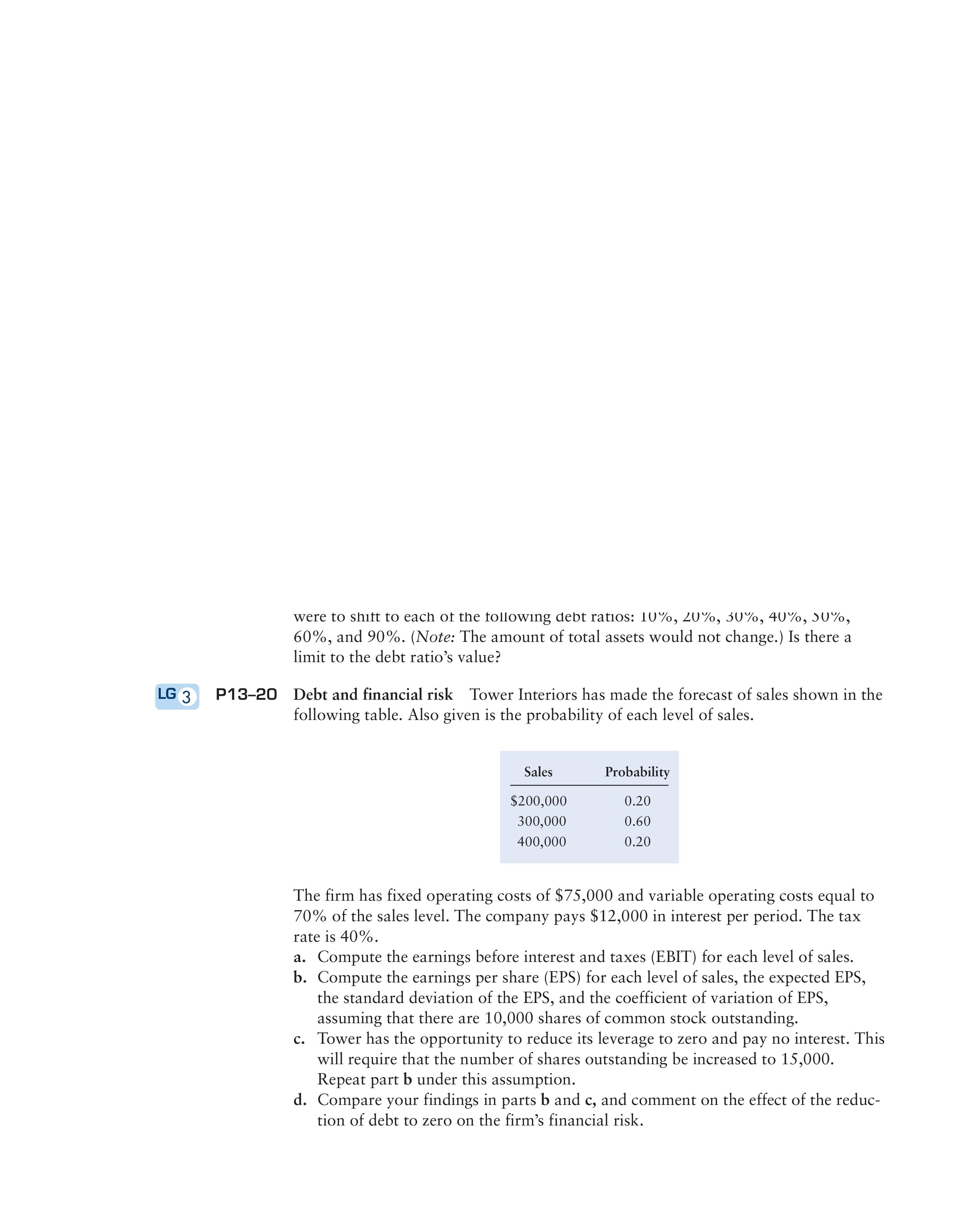

Example 13.6 3

DOL at base sales level Q =Q*(P-VC)

Q*(P-VC)-FC

CHAPTER 13 Leverage and Capital Structure 515

5. Technically, the formula for DOL given in Equation 13.5 should include absolute value signs because it is possible

to get a negative DOL when the EBIT for the base sales level is negative. Because we assume that the EBIT for the

base level of sales is positive, we do not use the absolute value signs.

6. When total revenue in dollars from sales—instead of unit sales—is available, the following equation, in which

TR total revenue in dollars at a base level of sales and TVC total variable operating costs in dollars, can be used:

This formula is especially useful for finding the DOL for multiproduct firms. It should be clear that because in the

case of a single-product firm, , substitution of these values into Equation 13.5

results in the equation given here.

TR =Q*P and TVC =Q*VC

DOL at base dollar sales TR =TR -TVC

TR -TVC -FC

==

focus on PRACTICE

Adobe’s Leverage

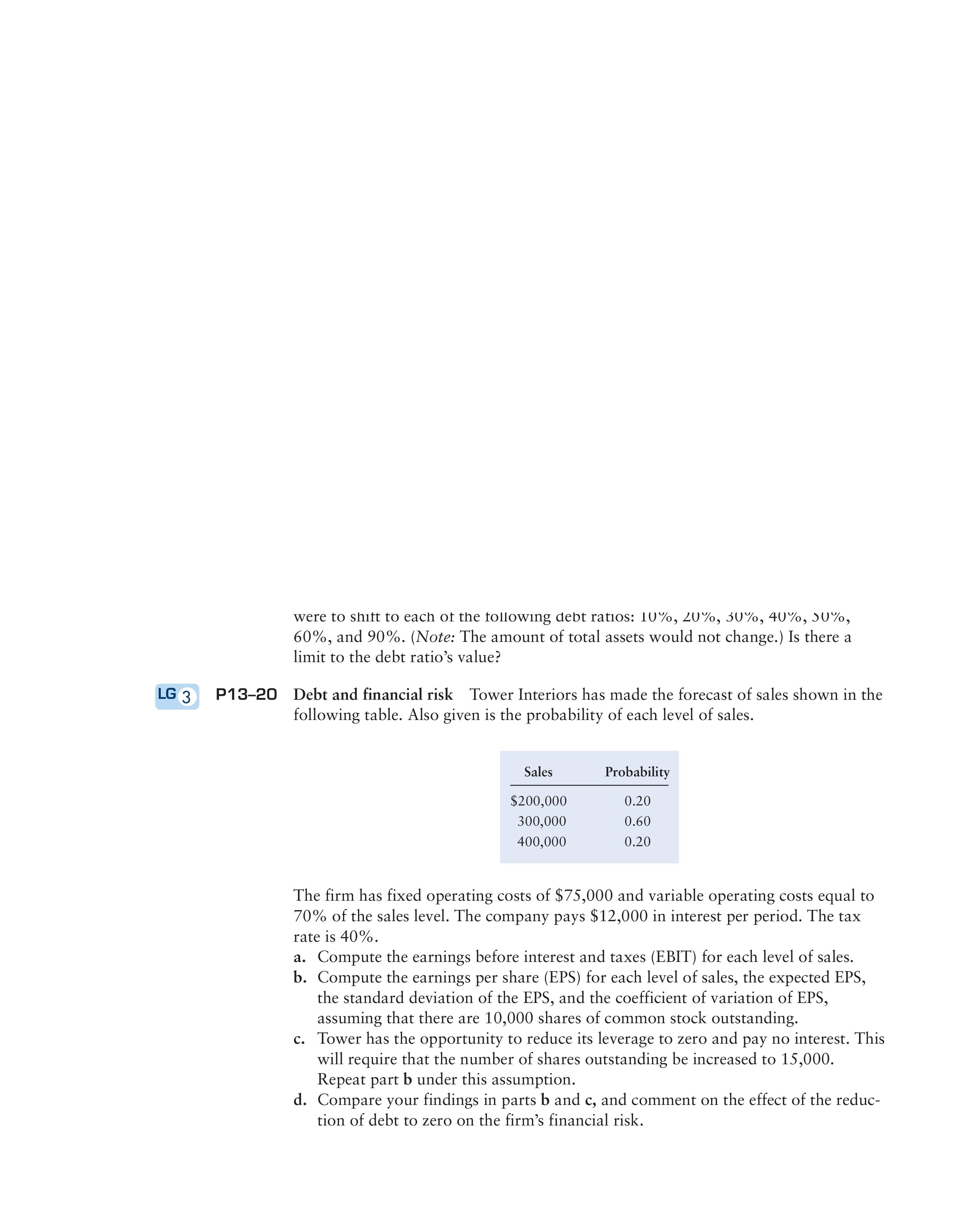

2009. A 22.6 percent increase in

2007 sales resulted in EBIT growth of

39.7 percent. In 2008, EBIT increased

just a little faster than sales did, but in

2009 as the economy endured a severe

recession, Adobe revenues plunged

17.7 percent. The effect of operating

leverage was that EBIT declined even

faster, posting a 35.3 percent drop.

3

Summarize the pros and cons of

operating leverage.

development and initial marketing stages.

The up-front development costs are fixed,

and subsequent production costs are

practically zero. The economies of scale

are huge: Once a company sells enough

copies to cover its fixed costs, incremen-

tal dollars go primarily to profit.

As demonstrated in the following

table, operating leverage magnified

Adobe’s

increase

in EBIT in 2007 while

magnifying the

decrease

in EBIT in

Adobe Systems, the

second largest PC soft-

ware company in the United States,

dominates the graphic design, imag-

ing, dynamic media, and authoring-tool

software markets. Website designers

favor its Photoshop and Illustrator soft-

ware applications, and Adobe’s

Acrobat software has become a stan-

dard for sharing documents online.

Adobe’s ability to manage discre-

tionary expenses helps keep its bottom

line strong. Adobe has an additional

advantage:

operating leverage,

the use

of fixed operating costs to magnify the

effect of changes in sales on earnings

before interest and taxes (EBIT). Adobe

and its peers in the software industry

incur the bulk of their costs early in a

product’s life cycle, in the research and

in practice

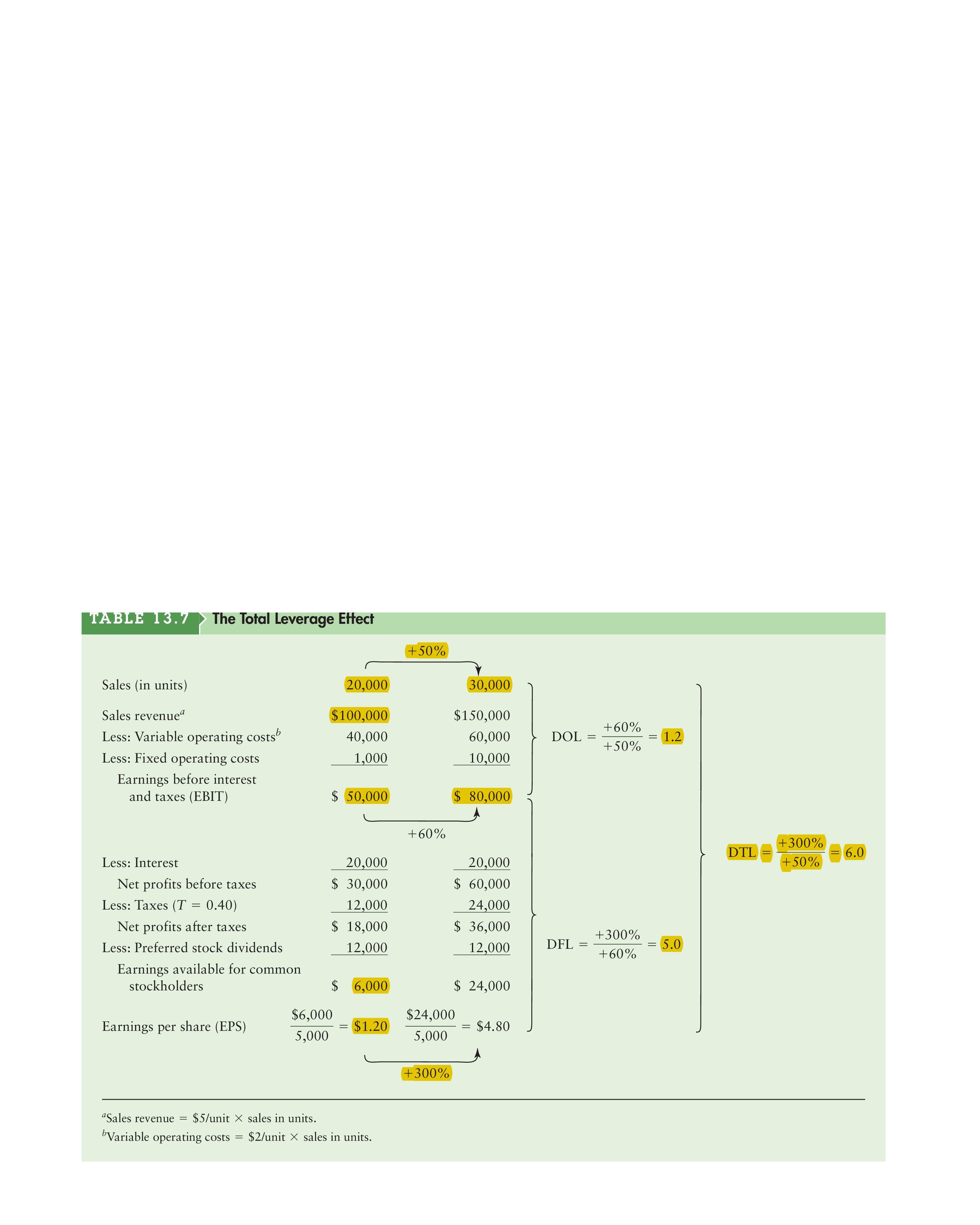

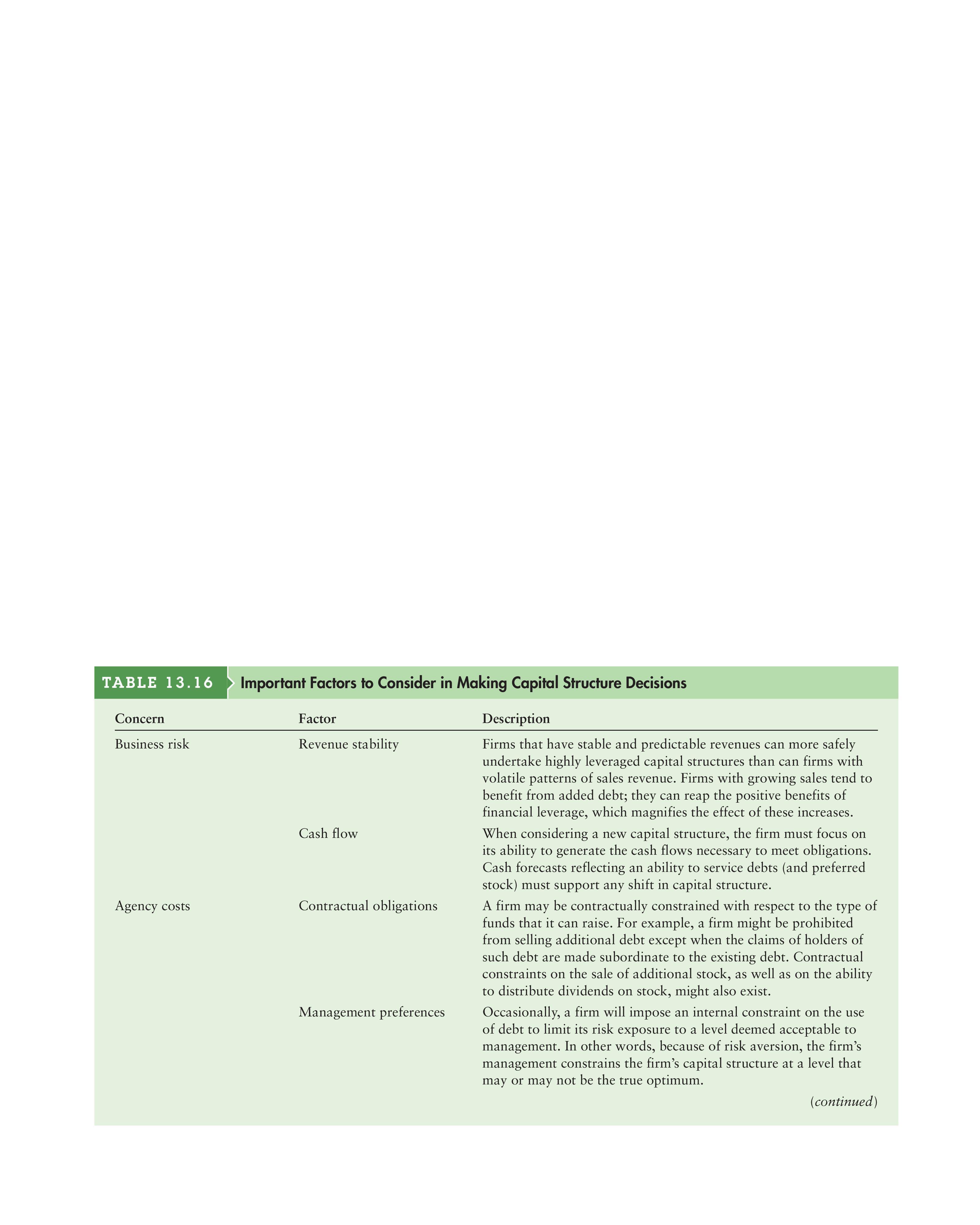

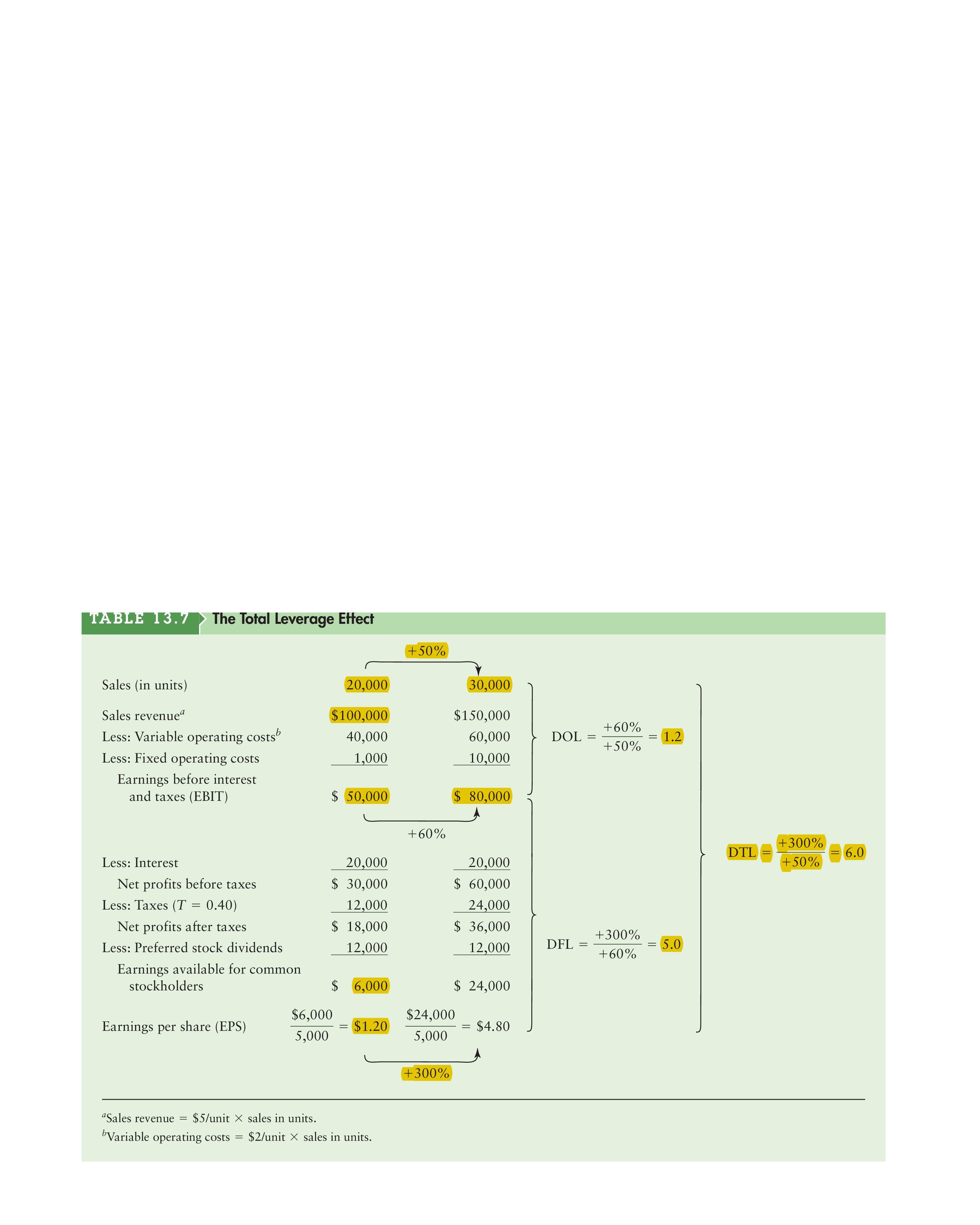

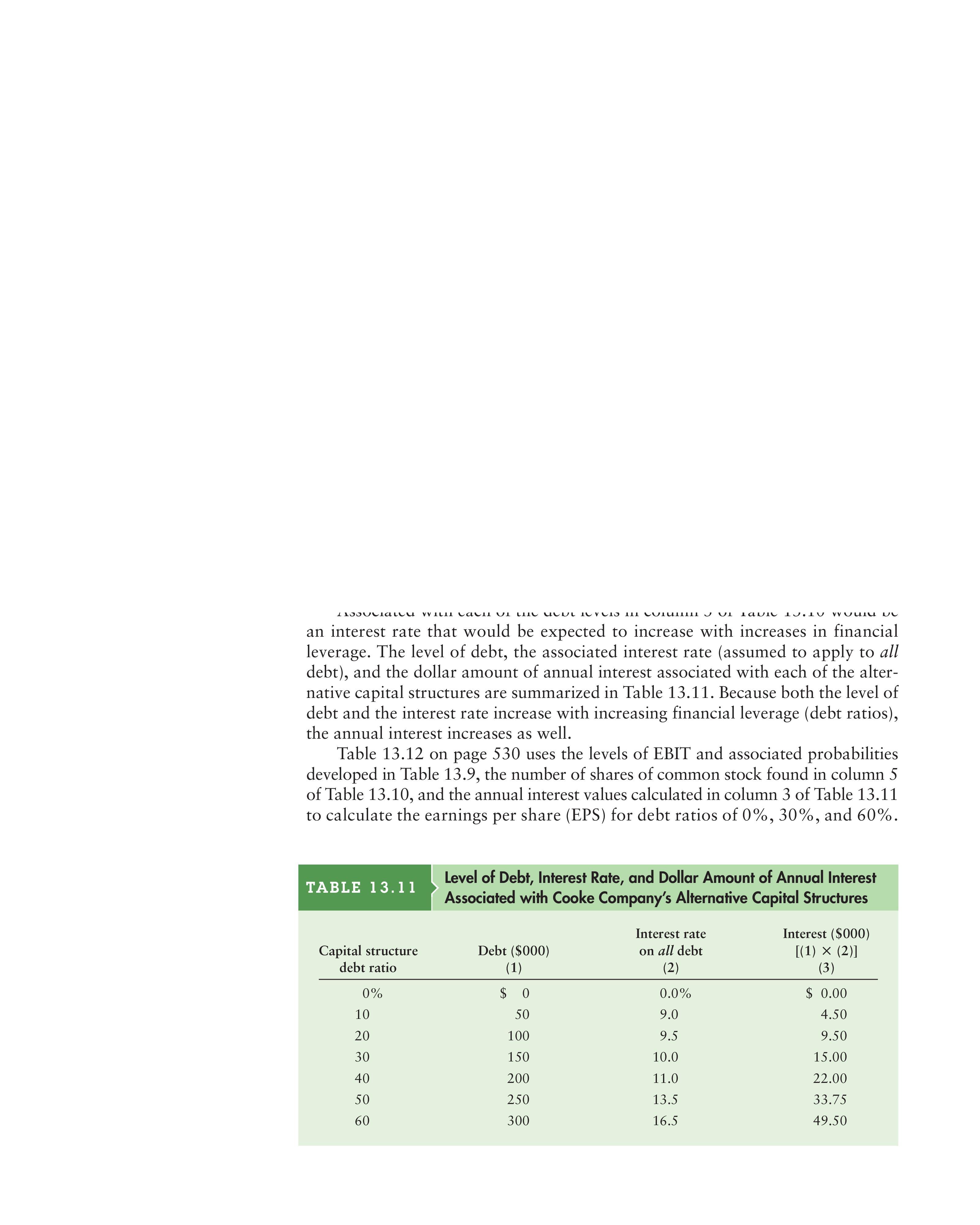

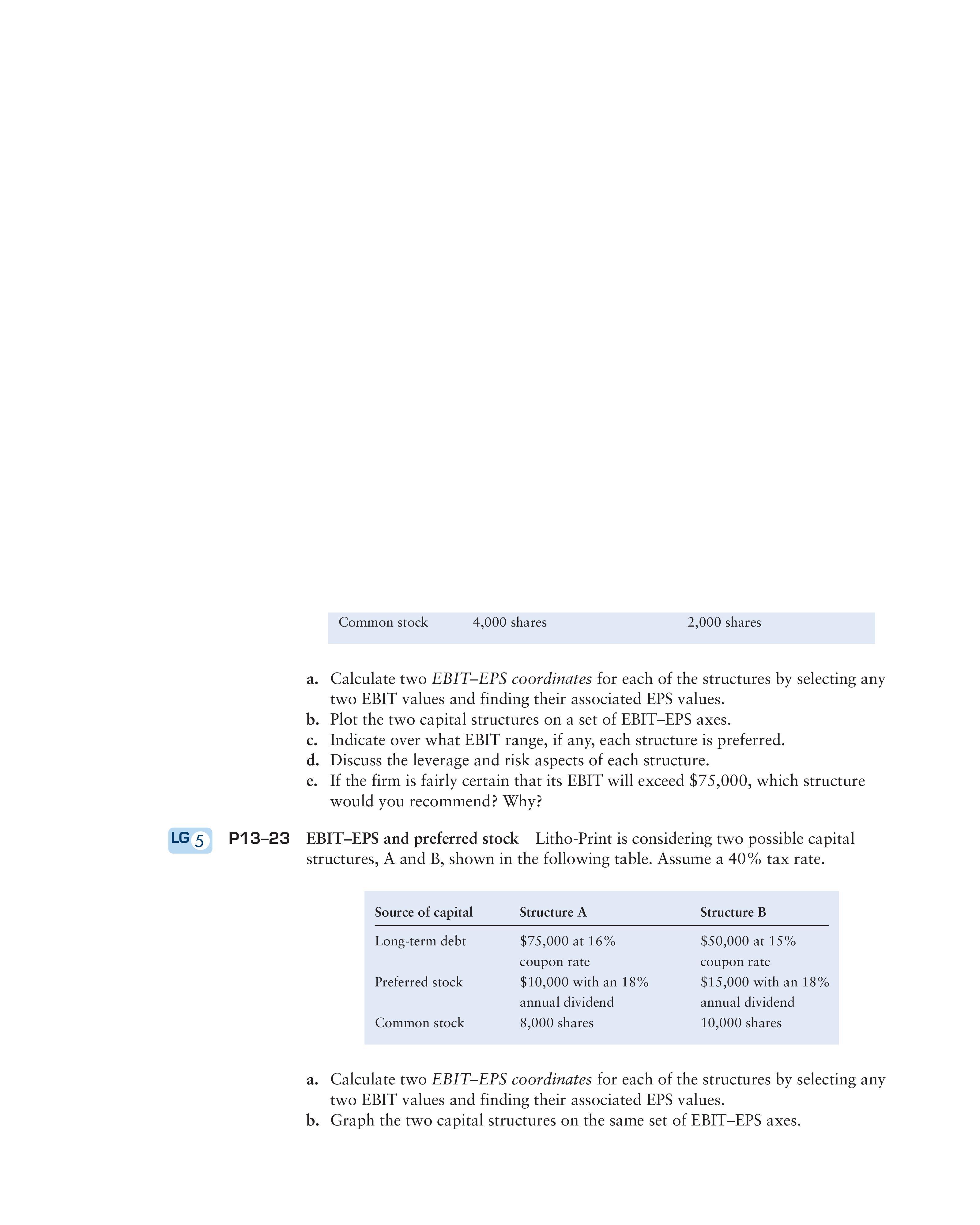

Item FY2007 FY2008 FY2009

Sales revenue (millions) $3,158 $3,580 $2,946

EBIT (millions) $947 $1,089 $705

(1) Percent change in sales 22.6% 13.4% ⫺17.7%

(2) Percent change in EBIT 39.7% 15.0% ⫺35.3%

DOL [(2)⫼(1)] 1.8 1.1 2.0

Source:

Adobe Systems Inc., “2009 Annual Report,” http.//www.adobe.com/aboutadobe/invrelations/pdfs/fy09_10k.pdf.