RESEARCH ARTICLE

Race, Neighborhood Economic Status,

Income Inequality and Mortality

Nicolle A Mode*, Michele K Evans, Alan B Zonderman

National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services,

Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America

*nicolle.mode@nih.gov

Abstract

Mortality rates in the United States vary based on race, individual economic status and

neighborhood. Correlations among these variables in most urban areas have limited what

conclusions can be drawn from existing research. Our study employs a unique factorial

design of race, sex, age and individual poverty status, measuring time to death as an objec-

tive measure of health, and including both neighborhood economic status and income

inequality for a sample of middle-aged urban-dwelling adults (N = 3675). At enrollment, Afri-

can American and White participants lived in 46 unique census tracts in Baltimore, Mary-

land, which varied in neighborhood economic status and degree of income inequality. A

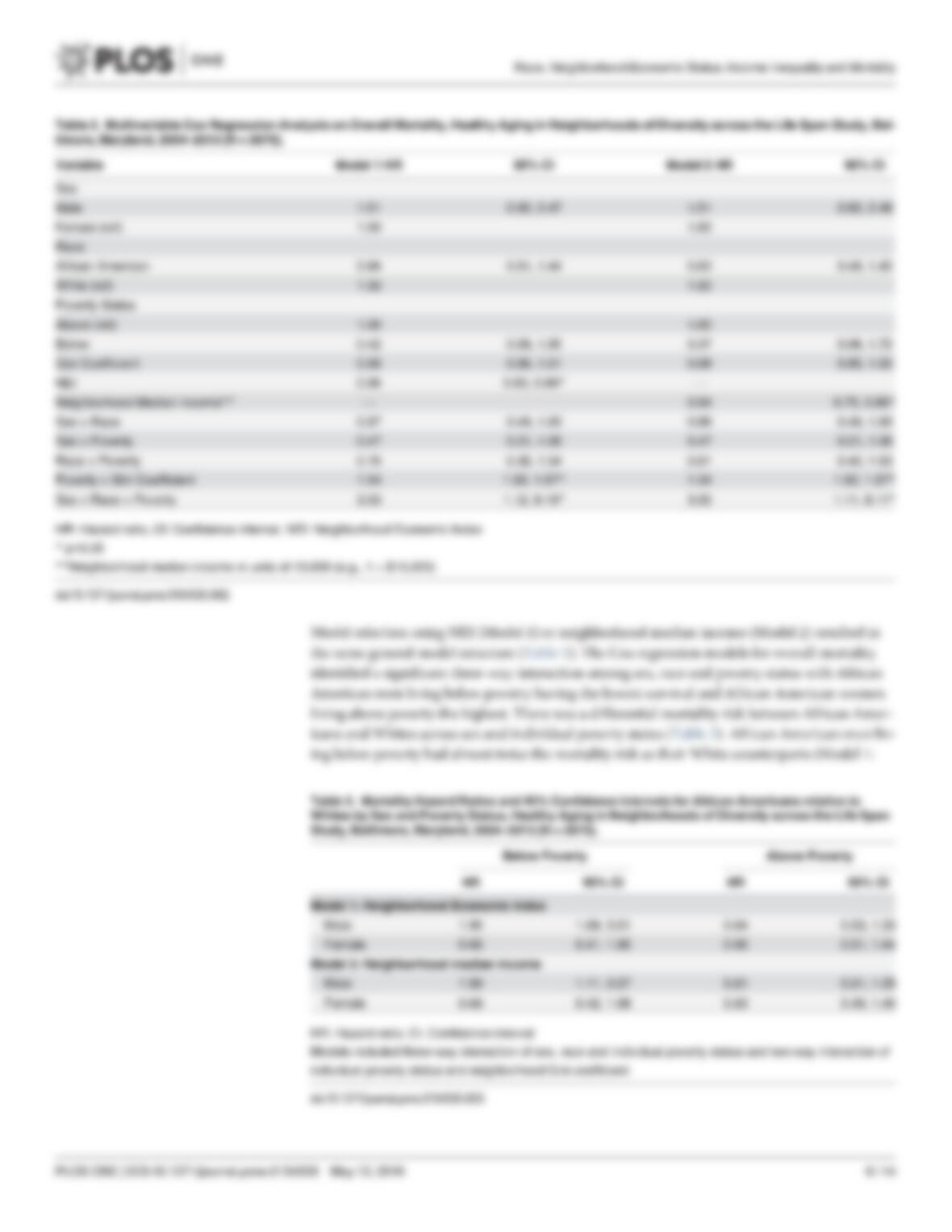

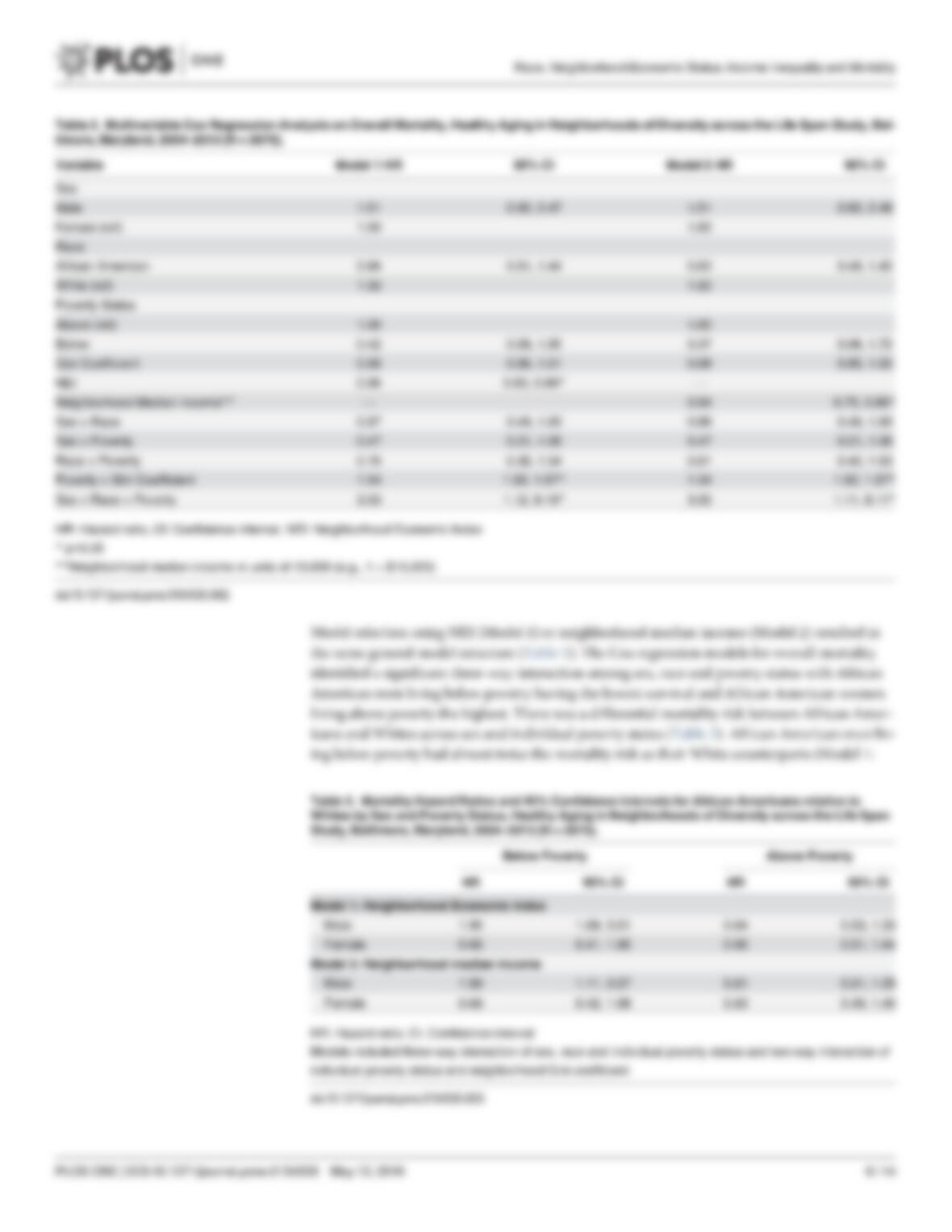

Cox regression model for 9-year mortality identified a three-way interaction among sex,

race and individual poverty status (p = 0.03), with African American men living below pov-

erty having the highest mortality. Neighborhood economic status, whether measured by a

composite index or simply median household income, was negatively associated with over-

all mortality (p<0.001). Neighborhood income inequality was associated with mortality

through an interaction with individual poverty status (p = 0.04). While racial and economic

disparities in mortality are well known, this study suggests that several social conditions

associated with health may unequally affect African American men in poverty in the United

States. Beyond these individual factors are the influences of neighborhood economic status

and income inequality, which may be affected by a history of residential segregation. The

significant association of neighborhood economic status and income inequality with mortal-

ity beyond the synergistic combination of sex, race and individual poverty status suggests

the long-term importance of small area influence on overall mortality.

Introduction

Mortality disparities across racial and economic groups in the United States (US) are well

established [1]. In 1995, African Americans had a 1.6 times greater overall mortality risk than

Whites; unchanged from the mortality disparity observed in 1950 [2]. Low socioeconomic sta-

tus (SES) is also associated with an increased mortality risk for the US population. For adults

over age 50, those in the lowest quartile of SES had 2.8 times the mortality risk as those in the

highest quartile of SES [3], and this disparity remained significant after controlling for major

risk factors (1.6 times). The influence of race and SES on mortality are difficult to parse because

PLOS ONE | DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0154535 May 12, 2016 1/14

a11111

OPEN ACCESS

Citation: Mode NA, Evans MK, Zonderman AB

(2016) Race, Neighborhood Economic Status,

Income Inequality and Mortality. PLoS ONE 11(5):

e0154535. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0154535

Editor: Donald R. Olson, New York City Department

of Health and Mental Hygiene, UNITED STATES

Received: October 2, 2015

Accepted: April 14, 2016

Published: May 12, 2016

Copyright: This is an open access article, free of all

copyright, and may be freely reproduced, distributed,

transmitted, modified, built upon, or otherwise used

by anyone for any lawful purpose. The work is made

available under the Creative Commons CC0 public

domain dedication.

Data Availability Statement: Data are available

upon request to researchers with valid proposals who

agree to the confidentiality agreement as required by

our Institutional Review Board. We publicize our

policies on our website https://handls.nih.gov.

Requests for data access may be sent to Alan

Zonderman (co-author) or the study manager,

Jennifer Norbeck at norbeckje@mail.nih.gov.

Funding: The Healthy Aging in Neighborhoods of

Diversity across the Life Span study is supported by

the Intramural Research Program (Z01-AG000513) of

the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of

Health (MKE, ABZ). Support was also provided by

the National Institute on Minority Health and Health