Page 4 9B15N011

STRIDES ARCOLAB LIMITED

History

Arun Kumar17 founded Strides — a first generation pharmaceutical company — in 1990 in Vashi, New

Bombay.18 Kumar recalled his early days in the mid-1980s at the Bombay Drug House, one of the first

Indian companies to export finished products, as well as his stint as a “buying agent” for European

companies. He had believed in following certain guiding principles in his business — namely, focusing

on exports, forging partnerships and concentrating on building scale-to-sell.

Within two years of its establishment, Strides had started exporting pharmaceutical products to Nigeria.

In 1994, the company received venture capital funding from Schroder Capital Partners, which became

a large stakeholder in Strides with a nearly 37 per cent stake. Arcolab — a Swiss customer of Strides

— provided Strides with a capital funding of $2 million in 1992, which proved to be an important

milestone in the evolution of Strides. In exchange, Strides changed its name to Strides Arcolab Limited

in 1996.

The early history of Strides, like that of most first-generation companies, was one of attention to critical

size and scale. “There was very little emphasis on strategy in the early phases of growth. Size was

critical, since we needed bankers to lend and customers to buy.”19 Strides entered foreign markets

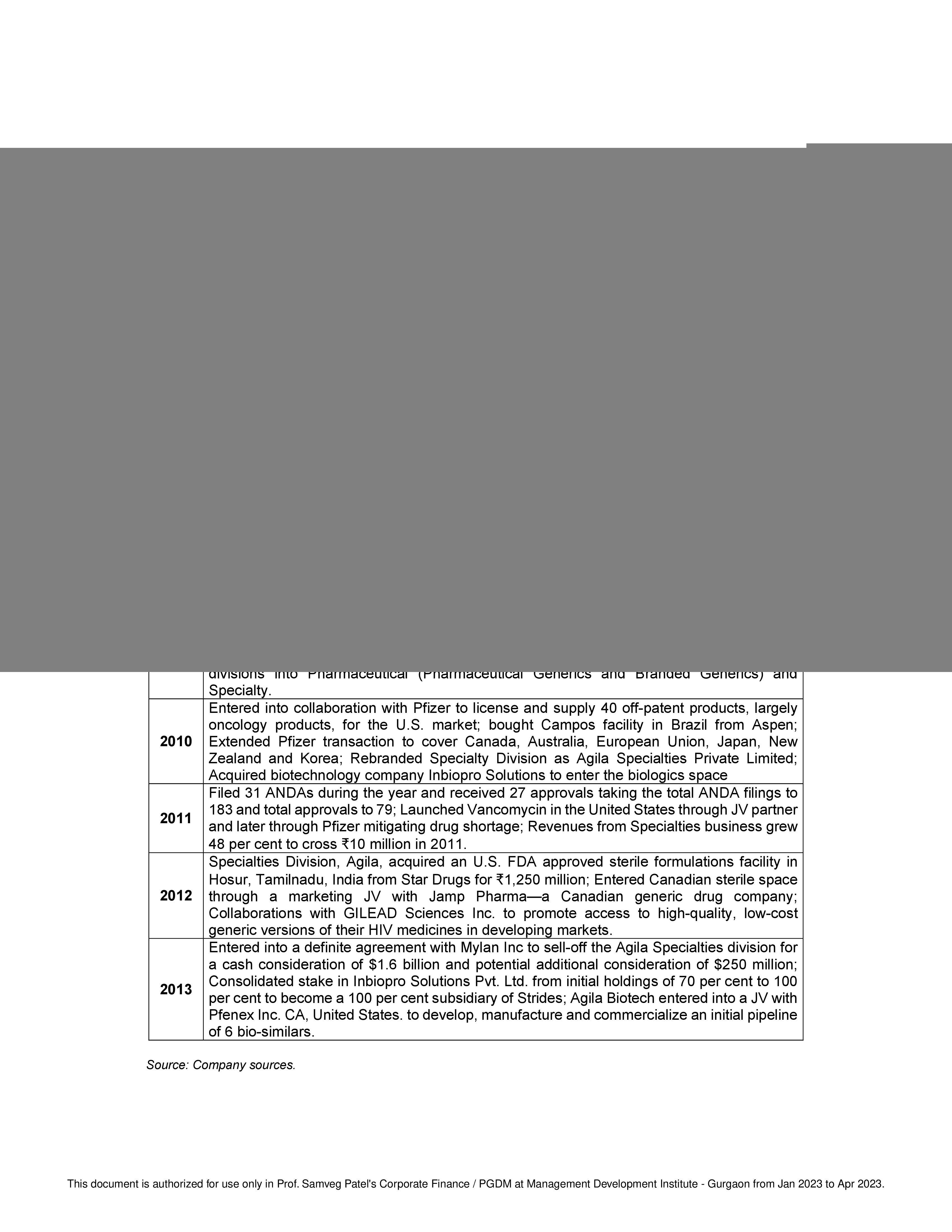

aggressively and also acquired both domestic and foreign companies during the period between 1990

and 2007 (see Exhibit 2). The company also became a listed company in this initial period, it was listed

with the National Stock Exchange in 2000 and with the Bombay Stock Exchange in 2002.

In the mid-2000s, Kumar started investing in research and development (R&D), in order to transform

Strides Arcolab Ltd. into a specialized pharmaceutical company. By 2008, he was convinced that in the

$900 billion pharmaceutical industry — into which Strides was a late entrant — the key to success lay

not in achieving critical size, but focusing on value. The $5 billion generic injectable drug segment was

a small but profitable niche within the global pharmaceutical industry. The high capital expenditure and

long gestation lags meant that this segment had very few players. The segment “represented a scarcity

domain,” said Kumar, one which he felt the need to tap into.

In 2010, with large, established U.S. players facing regulatory issues and a shortage of global players,

prices in the injectable drug market increased drastically, by as much as 150 times in certain cases.20

Kumar saw an opportunity in this, since Strides did not face compliance issues at this stage. He

established manufacturing facilities in nine locations across India, Brazil and Poland and invested in

R&D to create a portfolio of products.

Strides and the Injectable Drug Market

In 2009, the injectable drug market was worth $200 billion, and grew by 10 per cent to $220 billion in

2011. The market for generic injectable drugs was more lucrative than the branded injectable drug

market, and within this sector, the segments of biologics and oncological agents were relatively more

lucrative. At 38 per cent, the United States accounted for the largest chunk of the overall global

injectable drug market in 2011. It was estimated that the U.S. generic injectable sales would grow at a

CAGR of 10 per cent between 2012 and 2015.21

However, strict compliance norms meant that the number of global injectable manufacturing facilities

were limited. In 2010–2011 the United States witnessed a considerable shortage of injectable drugs.

The number of injectable drugs on the shortage list increased from 39 to 139 in 2011.22 Such shortages

were exacerbated by the long lead-time required to manufacture those injectable drugs, as well as a very

low rate of approval for generic alternatives that could have made up for the shortage.

This document is authorized for use only in Prof. Samveg Patel's Corporate Finance / PGDM at Management Development Institute - Gurgaon from Jan 2023 to Apr 2023.