4021 | Hansson Private Label, Inc.: Evaluating an Investment in Expansion

2 BRIEFCASES | HARVARD BUSINESS SCHOOL

Although he was worried about risk, Hansson was equally invigorated by the prospects of rapid

growth and significant value creation. He knew of numerous examples of manufacturers, both in

private label and branded businesses, who had risked their future by locking in a strong relationship

with a huge, powerful retailer. For many, the bet had delivered a big payout that lasted for decades.

Hansson’s employees had completed their fact-gathering and provided a multifaceted analysis of

the proposed project, which he now held in his hands. The time had come to do a final analysis on his

own and make a decision.

Company Background

HPL started in 1992, when Tucker Hansson purchased most of the manufacturing assets of Simon

Health and Beauty Products. Simon had decided to exit the market after struggling for years as a

bottom-tier player in branded personal care products. Hansson was a serial entrepreneur who had

spent the previous nine years buying manufacturing businesses and selling them for a profit after he

improved their efficiency and grew their sales. He bought HPL for $42 million—$25 million of his

own funds and $17 million that he borrowed—which was (and remained) the largest single

investment Hansson had ever made. Hansson was seeking to capitalize on what he saw as the

nascent but powerful trend of private label products’ increasing their share of consumer-products

sales. Although the concentration of his wealth into a single investment was risky, Hansson believed

he was paying significantly less than replacement costs for the assets—and he was confident that

private label growth would continue unabated.

Hansson’s assessment of private label growth prospects proved to be prescient, and his

unrelenting focus on manufacturing efficiency, expense management, and customer service had

turned HPL into a success. HPL now counted most of the major national and regional retailers as

customers. Hansson had expanded conservatively, never adding significant capacity until he had

clear enough visibility of the sales pipeline to ensure that any new facility would commence

operations with at least 60% capacity utilization. He now had four plants, all operating at more than

90% of capacity. He had also maintained debt at a modest level to contain the risk of financial distress

in the event that the company lost a big customer. HPL’s mission had remained the same: to be a

leading provider of high-quality private label personal care products to America’s leading retailers.

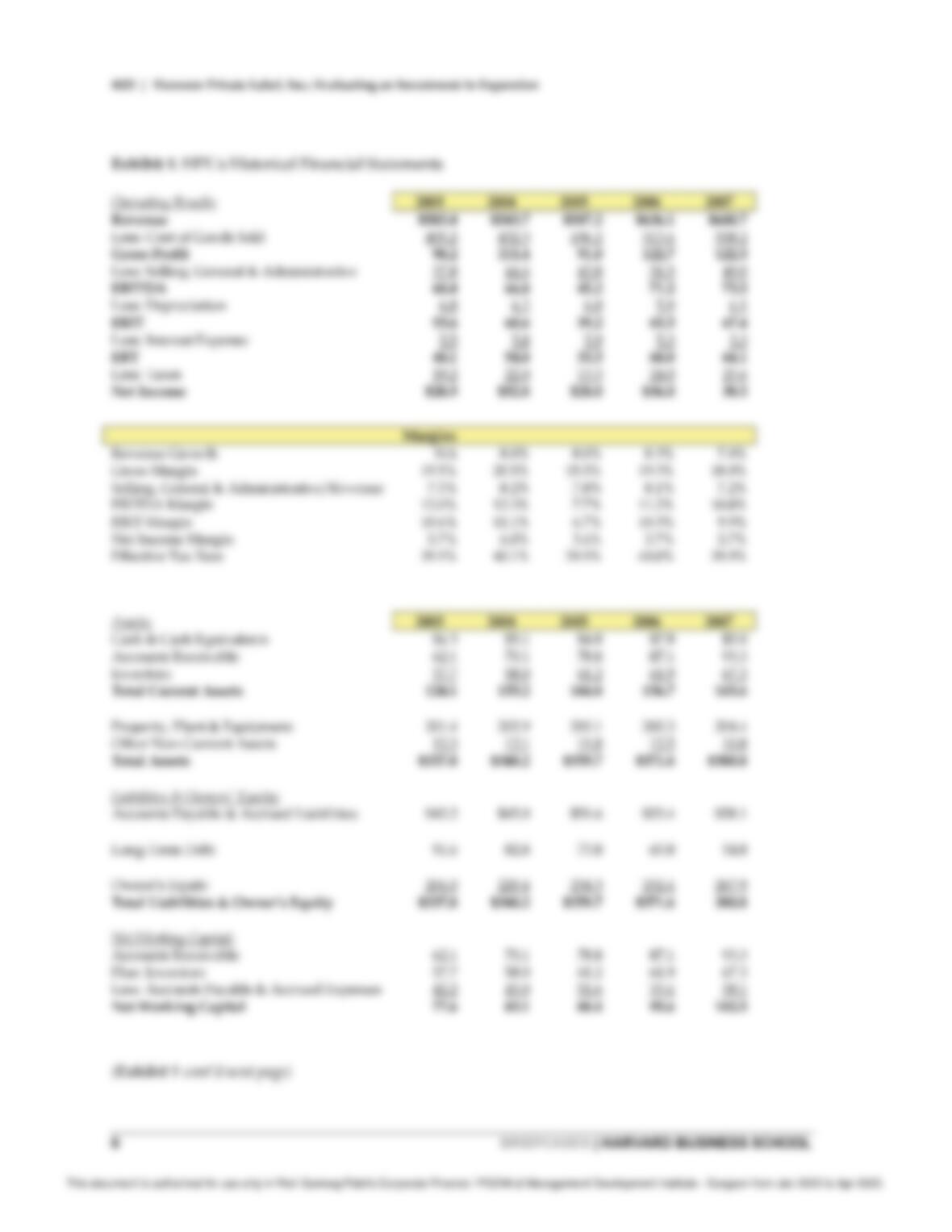

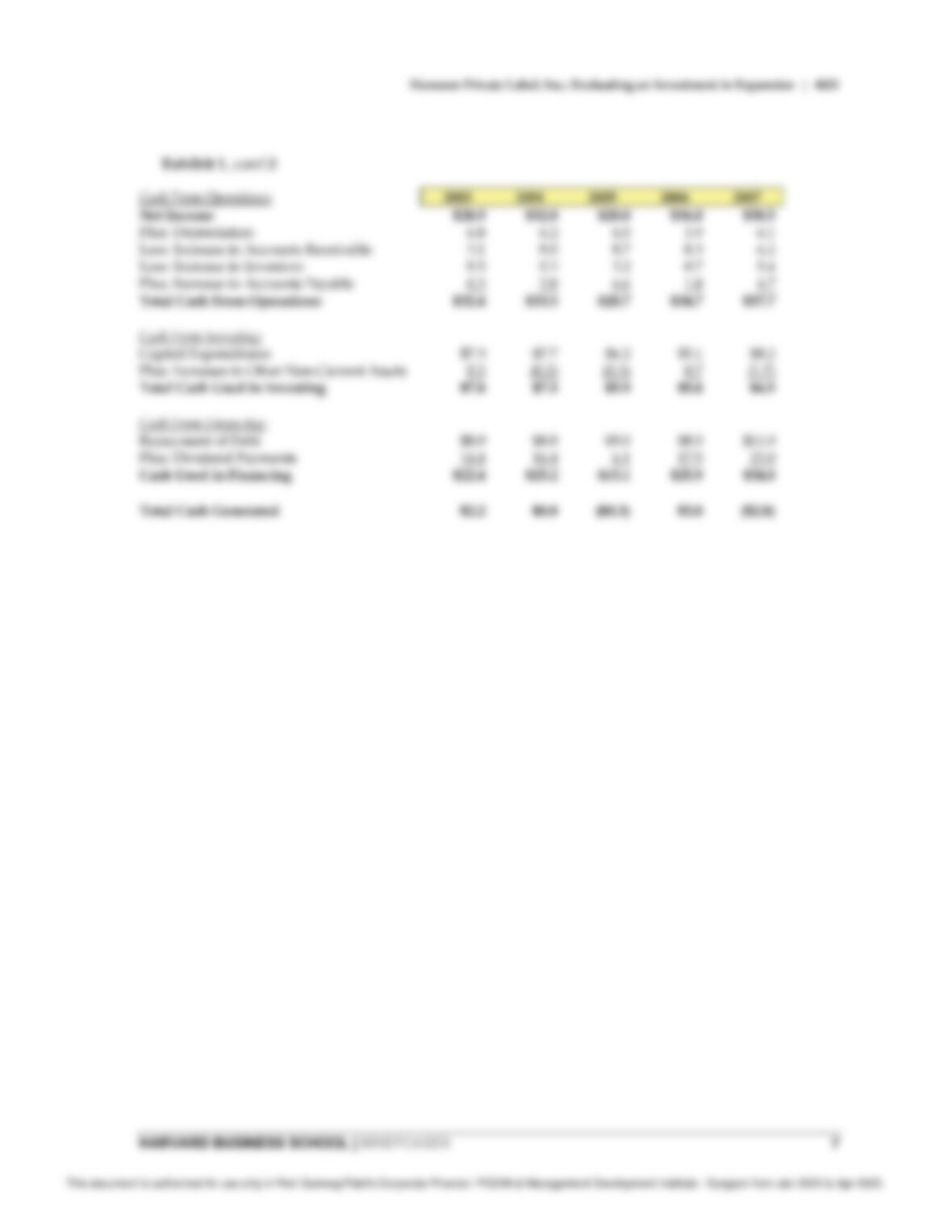

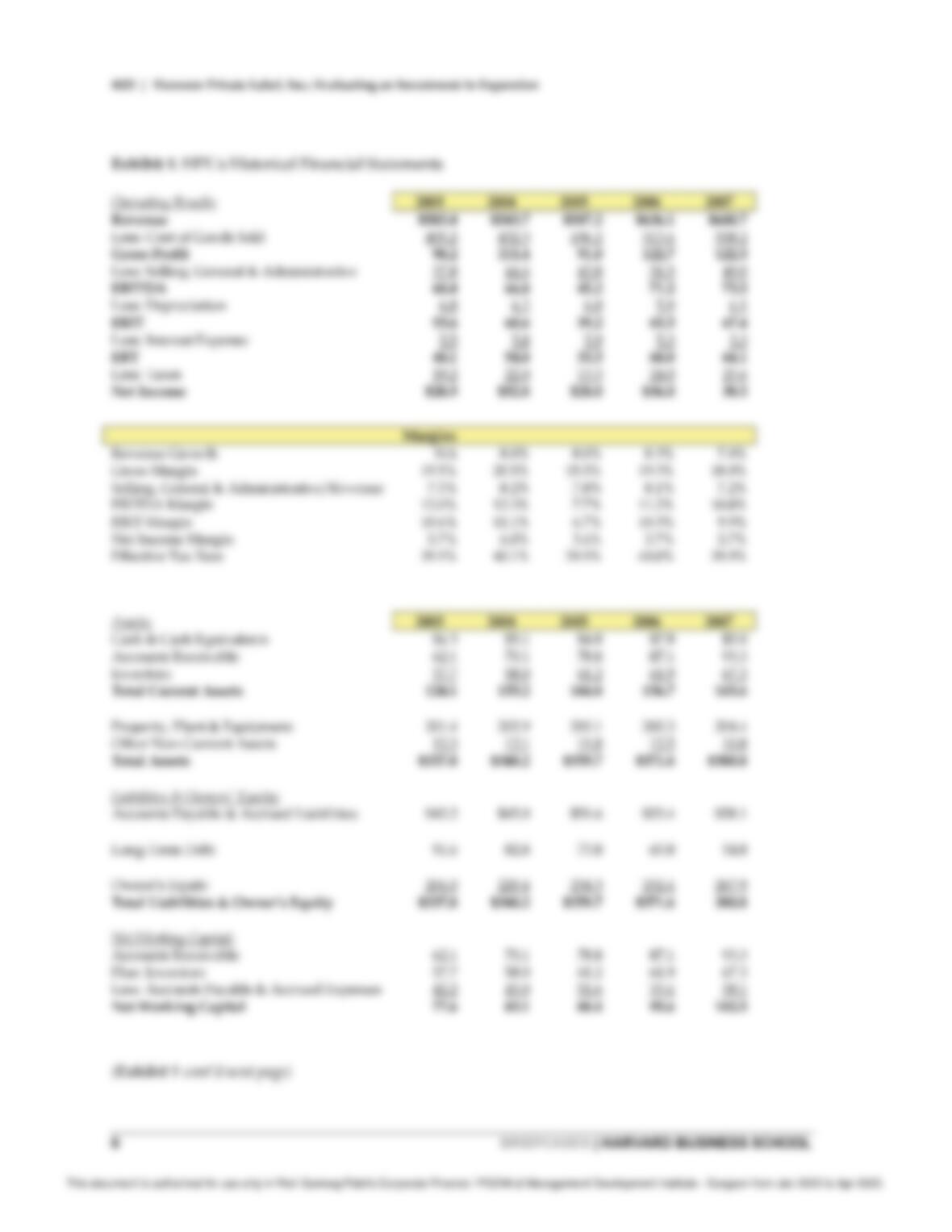

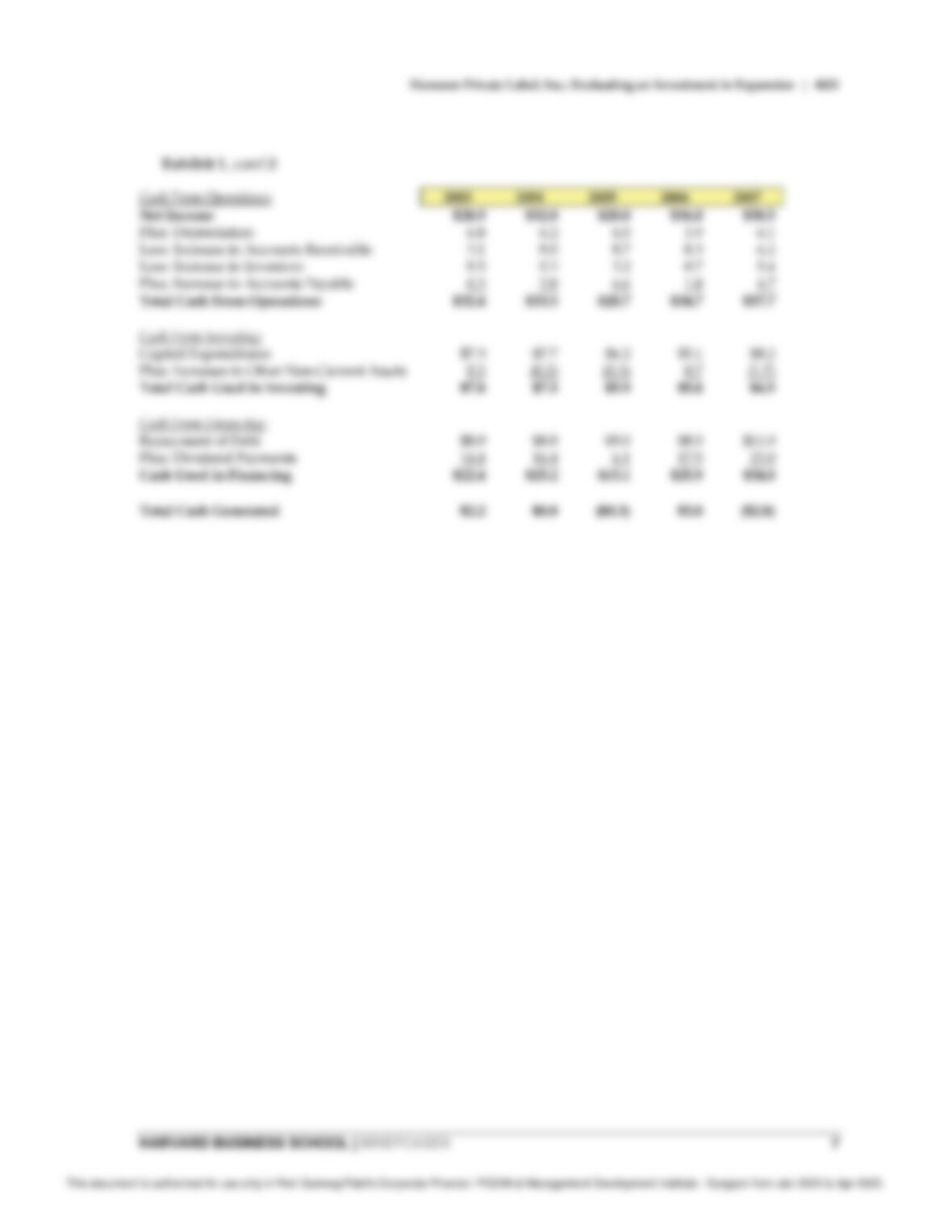

(See Exhibit 1, which presents HPL’s historical financial statements.)

The Market for Personal Care Products

The personal care market included hand and body care, personal hygiene, oral hygiene, and skin

care products. U.S. sales of these products totaled $21.6 billion in 2007. The market was stable, and

unit volumes had increased less than 1% in each of the past four years. The dollar sales growth of the

category was driven by price increases, which were also modest, averaging 1.7% annually during the

past four years. The category featured numerous national names with considerable brand loyalty.

Branded offerings ranged from high-end products such as Oral-B in the oral hygiene category to

lower-end names such as Suave in hair care. Private label penetration, measured as a percentage of

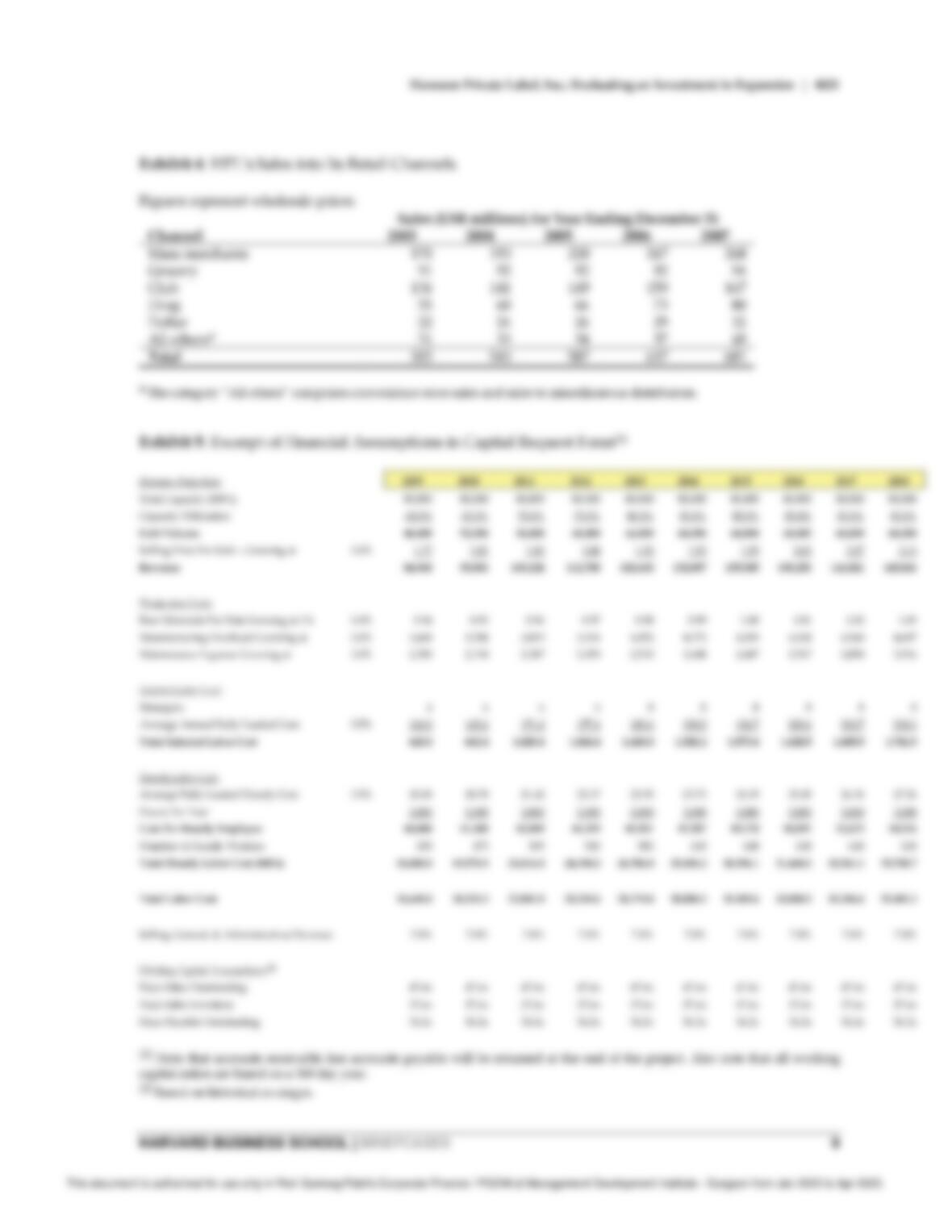

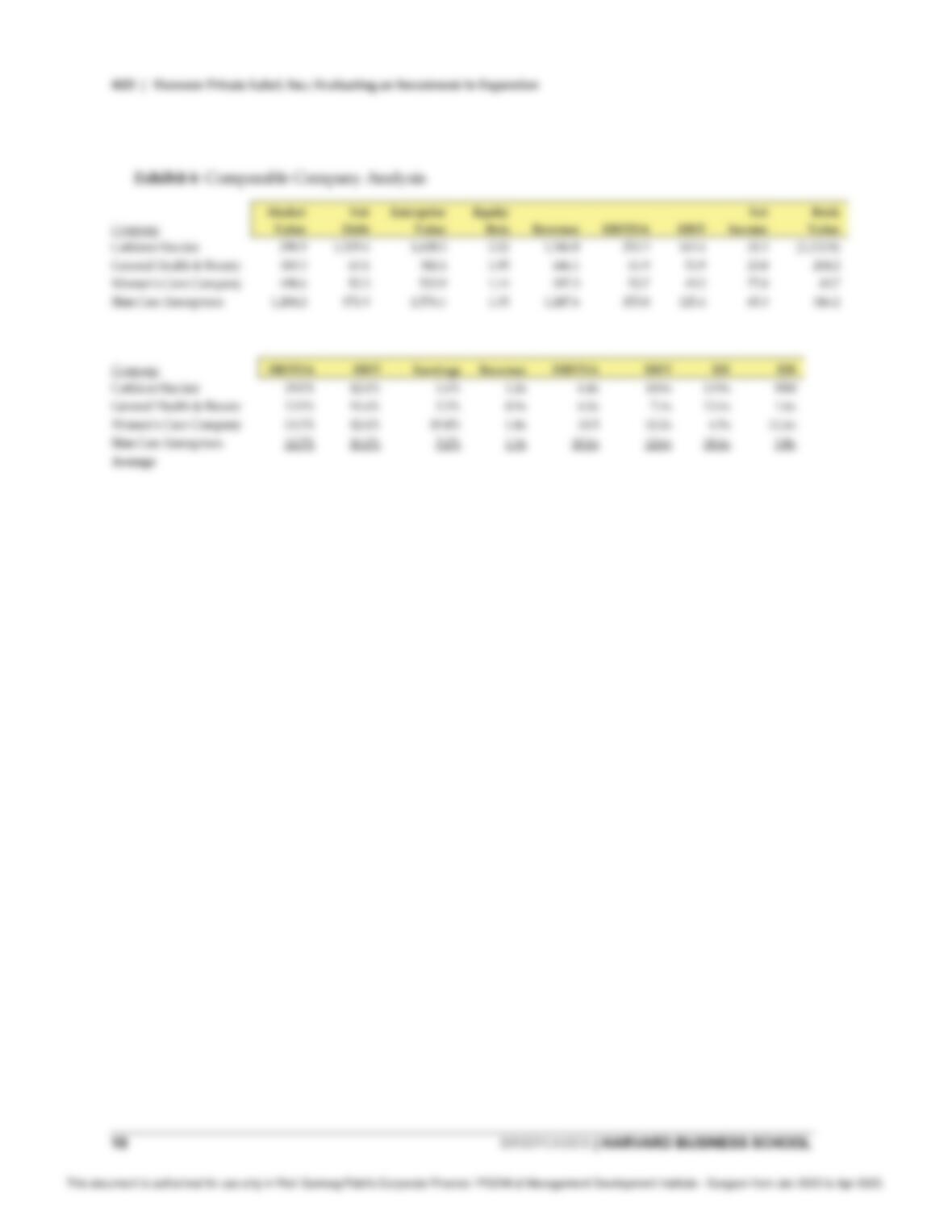

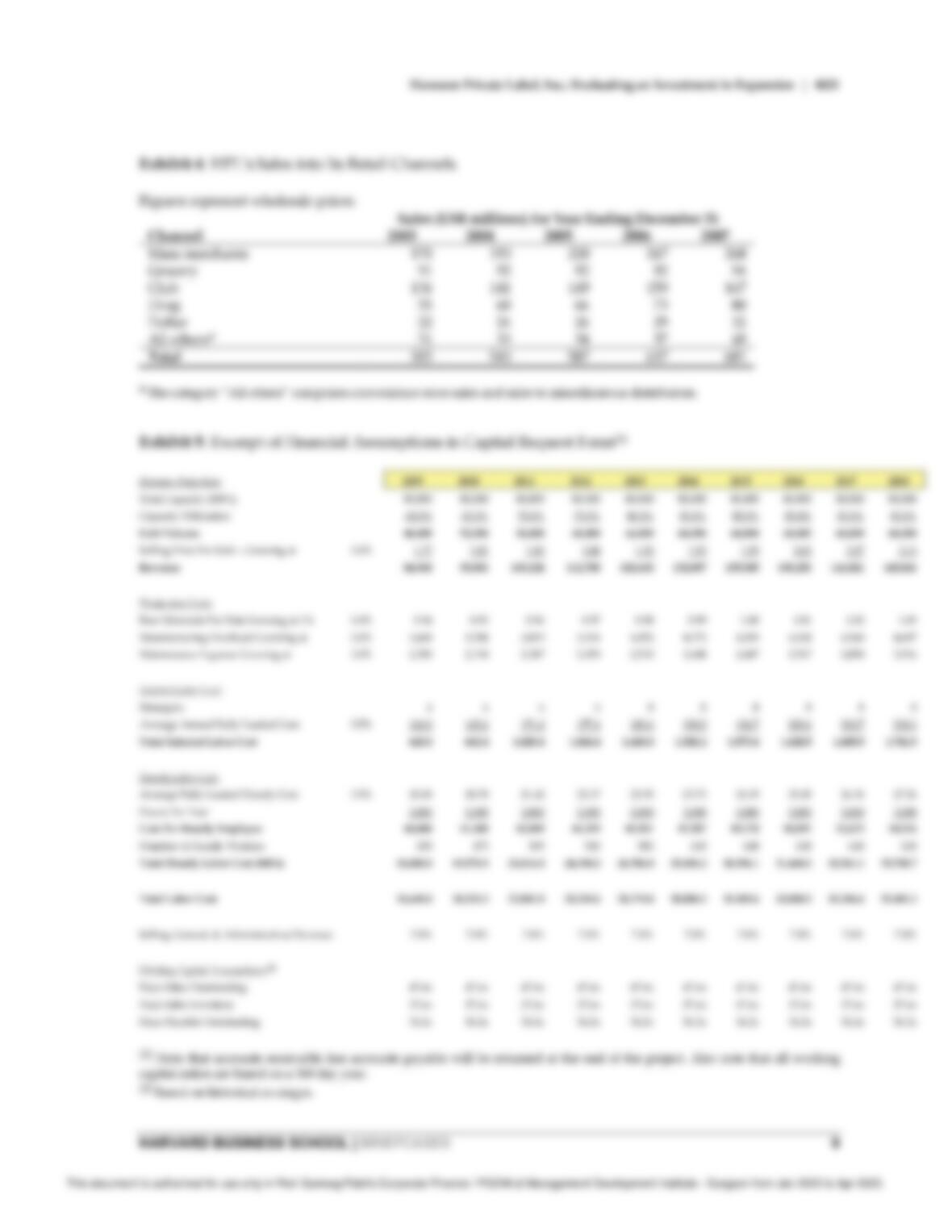

subsegment dollar sales, ranged from 3% in hair care to 20% in hand sanitizers. (Exhibits 2 and 3

present data about private label sales and market share.)

Consumers purchased personal care products mainly through retailers in five primary categories:

mass merchants (e.g., Wal-Mart), club stores (e.g., Costco), supermarkets (e.g., Kroger), drug stores

(e.g., CVS), and dollar stores (e.g., Dollar General). As a result of significant consolidation and growth

This document is authorized for use only in Prof. Samveg Patel's Corporate Finance / PGDM at Management Development Institute - Gurgaon from Jan 2023 to Apr 2023.