Du Pont: The Birth of the Modern Multidivisional Corporation 809-012

5

easy a target for federal antitrust actions, the company in 1908 began to investigate possible

alternative uses for nitrocellulose, the highly flammable material that is the main ingredient in

military gunpowder.15 Two years later, the firm made its first significant venture into the non-

explosives consumer market by purchasing the Fabrikoid Company, the country’s largest

manufacturer of a nitrocellulose-based artificial leather. This was followed by a tentative foray into

the production of pyroxylin, another nitrocellulose compound that was used to make plastics

products such as combs and eyeglass frames; lacquers; and photographic film.

Despite these early steps toward diversification, explosives still accounted for all but 3% of Du

Pont’s business in 1913.16 It was the breakneck expansion of the company’s physical, financial, and

personnel resources during the war—and the realization that it would be impossible to sustain those

resources as a munitions company in peacetime—that drove the serious search for new product lines.

Thus the paradox that the outsized success of Du Pont’s core munitions business is what led the

company to transcend and ultimately abandon it.

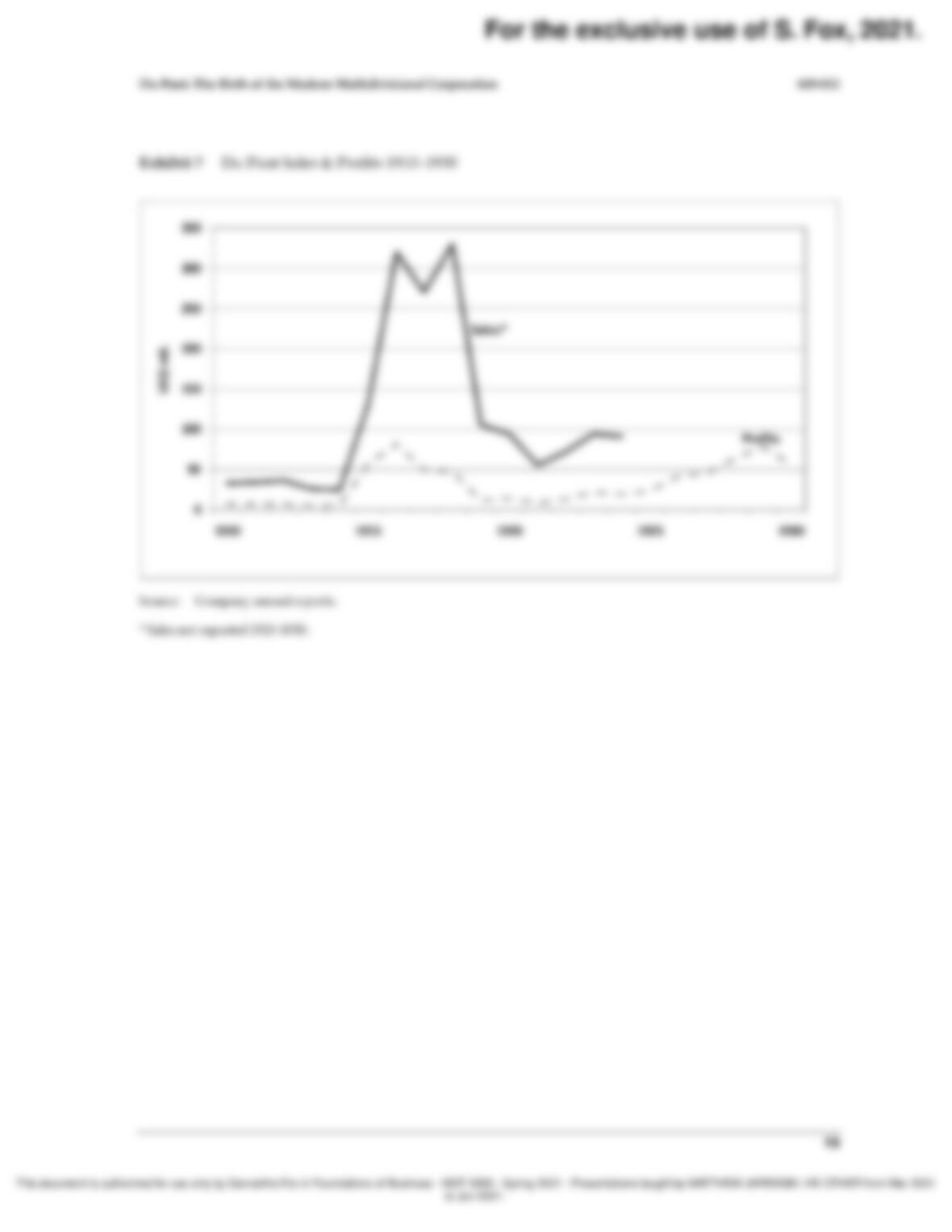

It is difficult to overstate the magnitude of Du Pont’s wartime boom. The company supplied some

40 percent of all the powder fired by Allied guns during the war. At the beginning of the conflict, the

firm was producing about one million pounds of nitrocellulose, the key ingredient of the smokeless

powder that fed those guns, per month. By war’s end, it was turning out 1.5 million pounds per day.

Du Pont’s workforce soared from 5,300 in 1915 to 85,000 in 1918. Its accumulated surplus (earnings

after paying out dividends) during that same period rose more than sevenfold, from $9 million to $68

million. Between 1913–1916, the company’s net profits shot from $6 million to $82 million—more

than the combined profits of every year since 1902, when the three du Pont cousins had bought the

company.17

Even during the war, Du Pont anticipated the challenges it would face when the guns fell silent.

“It is hoped,” the company stated in its 1915 annual report, “that new manufactures will be

developed to take the place of the abnormal military business.” Or as company Treasurer John J.

Raskob put it, “After the war it will be absolutely impossible for us to drop back to being a little

company again; and to prevent it, we must look for opportunities, know them when we see them,

and act with courage.”18

Du Pont did aggressively search out and develop new capacities even as it was racing to meet the

soaring wartime demand for munitions. This expansion extended both horizontally and vertically. In

1915, Du Pont bought the Arlington Company, a manufacturer of a brand of pyroxylin called Pyralin.

In 1916, it purchased the Fairfield Rubber Company, which produced Fabrikoid-based products such

as rubber-coated automobile and carriage tops. That same year, it decided to enter the paint and

varnish business (whose raw materials closely matched Du Pont’s existing capabilities), buying the

large integrated paint firm Harrison Bros. & Co. In 1917, it bought the Marokene Company, which

made a key ingredient in Fabrikoid. It also built a laboratory in New Jersey to study and manufacture

synthetic dyes, a product whose chemistry was closely related to that of high explosives and a market

15 Nitrocellulose is made by treating cellulose with concentrated nitric acid. (Cellulose is the stringy, fibrous material that

forms the main constituent of the cell wall in most plants, and is important in the manufacture of paper, textiles,

pharmaceuticals . . . and explosives.) When used in gunpowder, nitrocellulose is also known as guncotton.

16 Strategy and Structure, p. 78.

17 Adrian Kinnane, DuPont: From the Banks of the Brandywine to Miracles of Science, Wilmington, Delaware: E.I. du Pont de

Nemours and Company, 2002, p. 79; William S. Dutton, Du Pont: One Hundred and Forty Years, New York: Charles Scribner’s

Sons, 1949, p. 261; Strategy and Structure, p. 84; E. I. du Pont de Nemours & Company Annual Report, 1919, p. 16; DuPont: From

the Banks, p. 76.

18 Ernest Dale, “Du Pont: Pioneer in Systematic Management,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 2, No. 1 (Jun., 1957), p. 46.

For the exclusive use of S. Fox, 2021.

This document is authorized for use only by Samantha Fox in Foundations of Business - MGT 3050 - Spring 2021 - Presentations taught by MATTHEW JAREMSKI, HE OTHER from Mar 2021

to Jun 2021.